Not the Right Kind of Provocation

education coverage remains captured by orthodoxy on the left, right, and center

Helen Lewis dives into the reading wars for The Atlantic. You are likely already aware of this controversy, but if you aren’t, the basic story is that an earlier way to teach reading, phonics, is now considered more effective than a later method that became widespread, sometimes called whole language. This has led to all sorts of recriminations, which get laundered through the typical partisan lens. And the controversy has of course invited the kind of misguided hyperventilating about how we’re going to fix/disrupt/revolutionize schooling and education, close the achievement gaps or whatever, which is odd considering that many thousands of schools have taught reading using phonics and produced the same (normal) distributions of student ability that cause the endless gnashing of teeth about our supposedly-failing schools.

The piece is fine, fine enough; the consideration of how phonics has become a culture war football - whole language learning is woke, somehow - is particularly useful, if depressing. But Lewis’s article is also an indication of how, with education, our media is still clinging to an incredibly narrow script. We’re living in a period with a large and ever-growing branch of the media that’s willing to reconsider dominant narratives - sometimes intelligently, often not. Call it heterodox media or outsider media or whatever you want. Lewis has become a part of that wing of media, albeit on the more staid and traditionalist side; that The Atlantic, of all magazines, has cultivated a reputation recently as a heterodox-adjacent publication says curious things about modern media. (In particular, about how to stay alive financially in modern media.) Yet despite this friendliness with the contrarian side of the industry, the piece reflects the same stultifying conformity that absolutely dominates education coverage, maintains the same sclerotic attachment to the Official Dogma, refuses to ask the obvious and essential questions that underlie the phonics controversy. And yet nothing could be more valuable for our country than for a high-profile publication like The Atlantic to break with our broken consensus.

Let me first say, as something of an aside, that as Lewis suggests the pro-phonics case is not nearly the slam dunk people think it is. If you actually dig into the research record, the rapidly-congealed conventional wisdom that phonics instruction is far superior to the whole language model seems much more shaky than anyone lets on. As I’ve explained before, education research is uniquely challenging and has produced a raft of findings that were considered ironclad before that confidence was gradually chipped away. The most obvious example is pre-K; the value of smaller class sizes is another. More controversially, I would argue that a dominant majority of the relevant evidence suggests that more funding does not result in better outcomes in schooling, although people are doggedly attached to that one. The repeated failures of so-called “value-added modeling” are a good example of how embarrassing bad educational investigations can be. Things we “know” in education become, in time, things we thought we knew. I would also argue that comparative pedagogical research (like the kind comparing phonics to whole language) is among the very hardest to pull off, thanks to sample selection issues, model building issues, difficulty controlling for confounds, and endogeneity problems. Maybe someday I’ll have the time and energy to really go over the research here. (Yglesias has a pretty good consideration, and he links to this very useful post from Mark Seidenberg.) For now though I can only responsibly say that this is a big, stakes-laden issue that rests on a research finding that’s far less concrete than you’d hope.

Next, let me address repeated claims that the superiority of the phonics method somehow disproves my overall theory of education. I’ve laid that theory out here many times, so to spare regular readers I’m putting a synopsis in a footnote1. (Please consider all footnotes in this piece to be skippable, if you’re inclined to skip.) Alternatively, you could read my first book, while a long citation-laden version can be found here and a (relatively) more brisk version is here.

Relative to our purposes now - I am skeptical of the ability of just about any school-side intervention to close relative gaps between students; that is, I think a vast amount of evidence shows that there’s essentially nothing schools can do to consistently make 20th percentile students into 40th percentile students, let alone 80th percentile students. Certainly not consistently or at scale. But as the phonics controversy has bubbled along, some have said to me, hey, if a pedagogical intervention makes a difference, if there’s a better or worse way to teach reading, doesn’t that disprove your position? Wouldn’t a school that teaches phonics be meaningfully better than a school that teaches whole language, if the phonics advantage is real? A teacher who teaches phonics? And if those pedagogical decisions matter, and other pedagogical decisions matter, can’t you build a policy that puts the best pedagogy together and in that way make sure No Child Is Left Behind™? If there’s such a thing as better or worse pedagogy, doesn’t that suggest that the conventional story of education is right after all?

First, I’d again provide this link and point you to the discussion of absolute vs. relative learning, which is what’s most relevant here. Beyond that - think about it for two seconds. Let’s assume that there really is a meaningful advantage to teaching phonics over other methods. What would the outcome of teaching one or the other be in actual, real-world scenarios, given what we know about education and maturation generally?

If all students received phonics instruction, the absolute learning gains might (might) be higher for everyone, but the more talented kids would still learn to read with ease and the less talented kids would still struggle; there would be a real, measurable, consequence-laden difference in reading ability between students from different talent bands

If all students received whole language instruction, the absolute learning gains might (might) be lower for everyone, but the more talented kids would still learn to read with ease and the less talented kids would still struggle; there would be a real, measurable, consequence-laden difference in reading ability between students from different talent bands

If the less talented students received phonics instruction and the more talented received whole language, the perceptible performance gap between them would perhaps be artificially compressed, though by less than I think some people might assume; more to the point, there’s no way to actually do such a thing, hoarding the good pedagogy for only the worse students, and it would be educational malpractice anyway; the parents of the talented kids would revolt, and they would be right to do so

It’s common for people in the education debate to suggest that academic inequality is the result of the opposite dynamic - of the talented (or rich etc) kids getting access to higher quality pedagogy than the untalented (or poor etc), as if good teaching is sequestered away in private school ivory towers; this simply isn’t true, as there’s no secret pedagogical system that’s superior to conventional teaching, and pedagogy in public schools and private schools and charter schools is overwhelmingly the same; I assure you that public schools have access to phonics materials already

Even in a world where we somehow hoarded phonics instruction for only the untalented/poor/poorly performing, as the students grew and the Wilson effect settled in and individual talent asserted itself more and more, the talented would pull away from the less talented and whatever impact competing types of reading instruction once had would fade out, as all educational interventions eventually do; this is precisely what happens with pre-K, when research actually shows any initial pre-K gains at all.

Remember, the core claims of the education reform movement are that a) their preferred policies will result in better educational outcomes for students and b) this improvement will result in better job market and economic outcomes. The moral and political exigency of the movement depends on the idea that reforms would somehow reduce poverty, socioeconomic inequality generally, and racial inequality specifically. I’ve argued that the whole thing is based on incoherent premises, particularly given the fact that achieving those socioeconomic effects requires that the students at the bottom not just improve but improve far more than the kids at the top.2 If the phonics advantage fades like essentially all early childhood advantages do, the difference is not meaningful for economic outcomes; if the advantage applies to all children equally such that they all benefit to the same degree, the difference is not meaningful for economic outcomes. Meanwhile, both the disadvantages of race and class and the advantages of individual talent continue to dominate. I’m not unwilling to consider the possibility that teaching phonics might really have real and durable advantages over other methods. But when the phonics debate went national, it got pulled up into the same dynamic of overpromising and underdelivering. The odds that phonics will “fix” American education are exactly zero.

The nice thing, for me, is that I don’t need miscellaneous pedagogical advances to be part of some quixotic effort to “fix” education and in that way end racial inequality and similar ills. The trouble for the reformers is that they do.

Some students appear to respond better to phonics than other approaches, that’s a fact. Plenty of kids have thrived using whole language, that’s also a fact. I don’t say that as an argument that it’s as good as phonics or that we should teach using it. It is, however, a reminder that some kids are going to thrive no matter what. And some kids are going to struggle no matter what. Because talent is real. Surely that reality is as worthy of discussion as a dispute about pedagogical best practices that has received reams of coverage in our biggest periodicals, right? Apparently not. Apparently not. And I suspect the usual strawmanning and fear of controversy are to blame. As it often does, the same weird contradiction asserts itself: if you ask people directly if every student has the same aptitude for reading and if we should expect all kids to score exactly the same on reading assessments, they’ll say no; if you say that the existence of students who perform two sigma below the mean on reading assessments is simply what we should expect thanks to ordinary variability, that there’s always going to be kids who are simply on the wrong side of the talent curve and there always will be, those same people get offended. But those are, of course, just different ways of saying the same thing. And the fact that all of this phonics debate floats along without ever coming into contact with the most essential questions of individual talent and the inevitability of a distribution of ability… well, it’s par for the course.3

The subhead of the Atlantic piece (which of course Lewis did not write) reads “Lucy Calkins was an education superstar. Now she’s cast as the reason a generation of students struggles to read.” But of course, it’s simply not true to say that a generation of students struggles to read; a significant part of that generation are superlative readers, the kind of kids who never had to even think about how to read as some sort of organized educational activity. Students like that will always exist. And there is a significant part of future generations that will struggle to read with phonics or any other kind of instruction. Students like that will always exist. The question that confronts us is whether we’ll build a society that serves the needs of both kind of students - but that’s a question everyone in media prefers to avoid.

Lewis writes

a teacher must command a class that includes students with dyslexia as well as those who find reading a breeze, and kids whose parents read to them every night alongside children who don’t speak English at home.

Doesn’t this tossed-off hypothetical reference contain the whole damn thing, if you look deeply enough? Let’s set aside whether dyslexia is one thing or many things and whether or not it’s simply a term that we came up with to say that some people are poor readers, as a matter of compassion. Let’s just consider this as a matter of kids who are good at reading and kids who are bad. If we concede that this divide exists, if we think that there are some people who have a natural aptitude for reading or any other academic skill, and some who don’t, then this endless warring over minor pedagogical differences becomes very low-stakes indeed. If we know that what dominates in educational outcomes is not a variable of schools or teachers but of students, then we can go one by one by one through our different education debates and dismiss them as irrelevant. The whole world of education media spends its time picking over perpetual minor squabbles that are all vastly less important than the simple question of whether academic ability, like all human abilities, is to some degree innate and normally distributed throughout the population. In several places in her essay, Lewis brushes up against that question, and then skitters away. She’s far from alone.

Lewis’s piece is a reminder that there’s no dissident voices dissident enough to publish really challenging pieces about education. It’s a space that remains entirely shut down to the biggest questions in education, and all out of deference to beliefs that no one actually believes: that all students are capable of being star students, that vast social inequalities can be closed by teachers in the classroom in six hours a day, that students are blank slates that can be moved around the performance distribution at will, if we only care enough. Conservatives worship the concept of the self-made man, hate public schools and teachers and their unions, and have become the dominant force in the supposedly bipartisan reform movement. Liberals insist on mistaking the political norm of equality of rights, human value, dignity, and access to the good life for a false empirical claim about equality of ability. Centrists worship the meritocratic system and need to convince themselves that it’s fair and can produce mobility and abundance for everyone. Neoliberals need to justify the destruction of the labor movement and the eradication of American industry, which requires replacing empowered labor with “a college degree for everyone,” a vision of shared prosperity that arose only in response to the coordinated policy of deindustrialization. And everybody’s afraid of getting in trouble and would simply prefer to keep their heads down.

Education is an issue set where almost no one is happy with the status quo, where they keep trying the same kind of things to provoke change, and where those same things keep failing over and over again. It’s the same people stepping on the same rake over and over again and declaring that the next rake will do it. Meanwhile, we spend billions on schools and academic outcomes are hugely important for the lives of our young people. This should all be a recipe for lots of genuinely unorthodox thinking and a willingness to challenge basic assumptions. And yet no major issue in modern American political life, none, is more stuck in convention and bound by insight-obliterating cliches and empty posturing about “leaving kids behind.” After all these years, with the relentless failures of the education reform movement, and the constant reminder that failure is always an option, our educational debates are still hemmed in by self-righteous people and their nostrums about helping every child - while the tools of redistribution are sitting there, waiting to actually save poor kids.

I was reminded of all this recently when I was approached by a publication that, it’s fair to say, is high-profile, and we had an hour long discussion about running a piece on these themes, an articulation of my argument that we will always have an academic talent distribution and so we should work to build a humane economic system that protects the less capable with redistribution. They seemed quite enthusiastic about it. And then, suddenly, mysteriously, they weren’t interested anymore. No explanation; I guess it’s still too hot. Stuff like that’s happened to me for the past ten years. I suppose this argument is still a little too radical, despite its actual modesty, and despite the fact that half the media right now is patting itself on the back for its willingness to break with orthodoxy. And I’m left to tell people what they already know but don’t want to believe.

My argument, more or less, is that

Talent is real; different individual students have different intrinsic or inherent levels of academic talent or potential; aptitude for academic success varies just like every other human trait and is almost certainly normally distributed, meaning that some students are dramatically below the median in their overall propensity for success in school and that will never change

Accordingly, students sort themselves into ability bands very early in life and stay in those bands over the course of academic life, with remarkable fidelity

A huge amount of evidence demonstrates that student-side variables (individual variables, family variables, environmental variables) dominate school-side variables (“teacher quality,” “school quality,” pedagogical techniques, resources) in producing student performance

You can artificially produce differences through restricting access to education altogether or through severe neglect/abuse/etc, but when different people are schooled eventually their individual talent and desire to learn will overwhelm any temporary intervention or condition

Demographic differences in educational outcomes, like the notorious racial achievement gap, exist prior to formal schooling; it is thus irrational to blame them on teachers or schools; the vast number of variables that separate various demographic groups are far more likely to explain performance gaps than schools

Once we realize how minimal school-side influence is on individual student performance, we can recognize that teacher quality (as defined by improving quantitative metrics) might be real but of little practical value; school quality (again as defined by improving quantitative metrics) does not exist

If you want to improve the lives of struggling students, work to establish a social democratic state that ensures the material best interest of everyone.

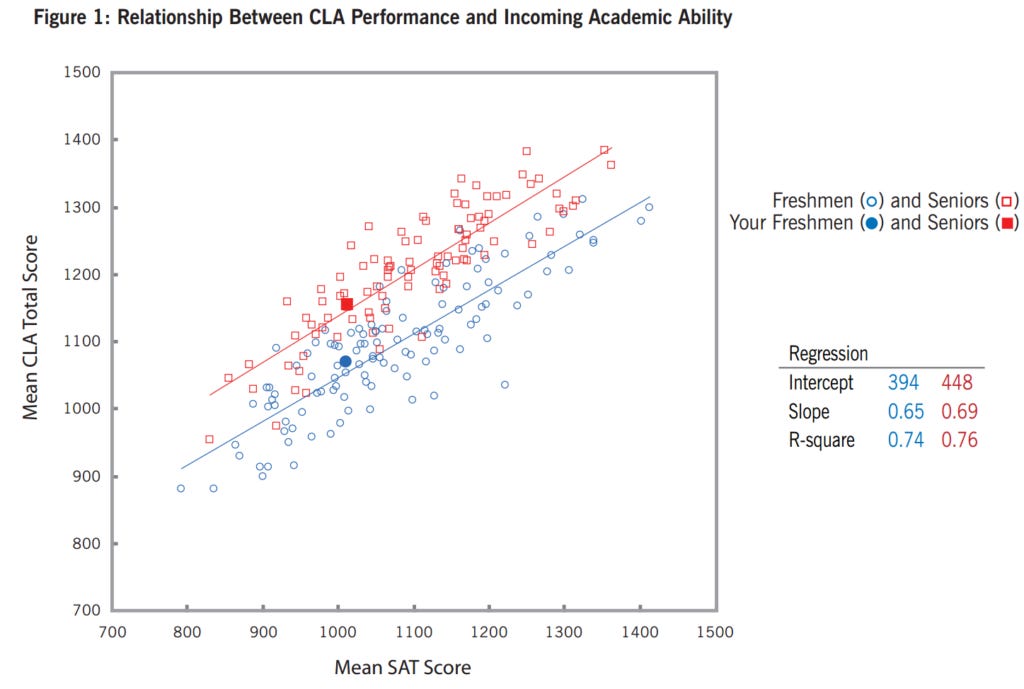

I bring this dynamic up all the time - the fact that, since the high-performing/white & Asian/rich kids keep learning too, absolute learning improvements among the low-performing/Black & Hispanic/poor kids are not sufficient; they must outgrow their higher-performing counterparts. I’m frequently amazed to find that many people dismiss this concern as some sort of gimmick or distraction. But it’s pretty much the whole entire problem! Again, it is relative academic performance which is rewarded in the labor market, and thus it is relative academic performance which has social justice valence. If the worst-performing improve but stay just as far behind because their peers are also improving, there is no financial advantage. I’ve used this image to illustrate this dynamic many times before; the actual data isn’t of much interest, but the broader dynamic it demonstrates is very important:

This graph shows the performance of dozens of colleges and universities on the CLA, a standardized test of college learning. Blue dots represent the average institutional performance of freshmen at a given school; red dots, senior performance. As you move up the Y access, CLA scores get better. As you move along the X access, the average SAT score of students prior to entry goes up; put another way, as you move right, the colleges get more selective. Which means that we can look at how students learned from freshman to senior year while also seeing their pre-entry ability. The nice gap between the blue and red regression lines shows robust learning for essentially all the schools, which is nice. But because the kids on the righthand side of the graph kept learning too, they are no better off than they were when they started college, relative to the smart kids - and they are going into the labor market competing against the smart kids.

If you could actually get into the heads of the many people who are treating phonics instruction like a miracle drug for all that ails education, I’m quite confident that what you’d find, very often, is not a deracinated perspective on literacy education as such but instead the same old desire: to make it so that no students struggle, so that no students are “left behind.” But that is, I’m afraid, not a desire that’s congruent with reality. There is a distribution of ability and there always will be. We can address troubling gaps in performance between groups, though again there’s no reason to think that they can be closed at the school side, given the evidence and the reality of American inequality. But even if we waved a magic wand and redistributed every demographic group in proportion with their population size across the performance spectrum, ensuring that there were no group gaps at all, we’d still be left with half the students in the bottom half, 20% in the bottom quintile, and tens of thousands of poor souls two standard deviations below the mean. This is a basic and immutable facet of reality.

Why the focus on narrowing the gap between the best and worst students? Isn’t it worthwhile to have everyone be better readers?

Agree with Freddie's longstanding point that expecting public schools to correct economic disparities is foolish. But I don't think relative academic performance is the only perspective that matters. I'd argue that improving basic reading and math proficiency for the bottom ~50% of students would have positive social impacts, even if all of those students remain in the bottom 50%.

This perspective is not expecting schools to make low performing kids "smarter" but rather pushing/supporting those students to perform closer to their own individual potential.