Education Doesn't Work 2.0

a comprehensive argument that education cannot close academic gaps

This is the first (and may prove to be only) time that I have updated a previous post to improve it. I am doing so because the basic observation outlined here is core to my view of education and society and I was dissatisfied with the first attempt. The original post will remain up for posterity.

A depressing-to-some Tweet that’s part of a much larger genre:

Click through to the tweet and you’ll see in the thread that learning to play an instrument, learning a second language, and playing sports have no cognitive or educational advantages either. (The professor behind the thread rightly notes that these things are good in and of themselves, which I’ve been sure to stress in the past myself.) Because of fundamental difficulties in researching education, correlation is constantly mistaken for cause - that is, students who are strong or weak in educational metrics will also non-randomly be associated with things we might want to study as causative, such as learning to play chess. When we get high-quality randomized research, we very often see results like the above, that the association is not causative and that the variable has no effect. I have been saying this for ten years, and it’s a dominant theme of my first book: in education research, if you just keep betting on the null, you’ll never go broke. Put more simply and sadly, nothing in education works. Student outcomes are remarkably sticky even in the face of considerable intervention.

This perspective is both buttressed by a tremendous amount of evidence and yet considered impermissible in polite debate. And teachers and schools pay the price, as they are asked to control outcomes they have limited influence on. The abstract of this paper sums up the reality.

Over the last 50 years in developed countries, evidence has accumulated that only about 10% of school achievement can be attributed to schools and teachers while the remaining 90% is due to characteristics associated with students. Teachers account for from 1% to 7% of total variance at every level of education. For students, intelligence accounts for much of the 90% of variance associated with learning gains.

The brute reality is that most kids slot themselves into academic ability bands early in life and stay there throughout schooling. We have a certain natural level of performance, gravitate towards it early on, and are likely to remain in that band relative to peers until our education ends. There is some room for wiggle, and in large populations there are always outliers. But in thousands of years of education humanity has discovered no replicable and reliable means of taking kids from one educational percentile and raising them up into another. Mobility of individual students in quantitative academic metrics relative to their peers over time is far lower than popularly believed. The children identified as the smart kids early in elementary school will, with surprising regularity, maintain that position throughout schooling. Do some kids transcend (or fall from) their early positions? Sure. But the system as a whole is quite static. Most everybody stays in about the same place relative to peers over academic careers. The consequences of this are immense, as it is this relative position, not learning itself, which is rewarded economically and socially in our society.

This phenomenon is relevant to the question of genetic influence on intelligence, but this post is not about that. The evidence of such influence appears strong to me, and opposition to it seems to rely on a kind of Cartesian dualism. However, one need not believe in genetic influence on academic outcomes to recognize the phenomenon I’m describing today. Entirely separate from the debate about genetic influences on academic performance, we cannot dismiss the summative reality of limited educational plasticity and its potentially immense social repercussions. What I’m here to argue today is not about a genetic influence on academic outcomes. I’m here to argue that regardless of the reasons why, most students stay in the same relative academic performance band throughout life, defying all manner of life changes and schooling and policy interventions. We need to work to provide an accounting of this fact, and we need to do so without falling into endorsing a naïve environmentalism that is demonstrably false. And people in education and politics, particularly those who insist education will save us, need to start acknowledging this simple reality. Without communal acceptance that there is such a thing as an individual’s natural level of ability, we cannot have sensible educational policy.

Kids do learn at school. You send your kid, he can’t sing the alphabet song, a few days later he’s driving you nuts with it. Sixteen-year-olds learn to drive. We handily acquire skills that didn’t even exist ten years ago. Concerns about the Black-white academic performance gap can sometimes obscure the fact that Black children today handily outperform Black children from decades past. Everyone has been getting smarter all the time for at least a hundred years or so. So how can I deny that education works?

The issue is that these are all markers of absolute learning. People don’t know something, or don’t know how to do something, and then they take lessons, and then they know it or can do it. From algebra to gymnastics to motorcycle maintenance to guitar, you can grow in your cognitive and practical abilities. The rate that you grow will differ from that of others, and most people will admit that there are different natural limits on various learned abilities between individuals; a seasoned piano teacher will tell you that anyone can learn some tunes, but also that most people have natural limits on their learning that prevent them from being as good as the masters. So too with academics: the fact that growth in absolute learning is common does not undermine the observation that some learners will always outperform others in relative terms. Everybody can learn. The trouble is that people think that they care most about this absolute learning when what they actually care about, and what the system cares about, is relative learning - performance in a spectrum or hierarchy of ability that shows skills in comparison to those of other people.

If Harvard (or Caltech or whoever) selected an incoming freshman class, and then aliens came to earth and abducted every one of them, Harvard would just reach into their bag of valedictorians and admit the next rung of students on their list. Those students would presumably have meaningfully lower ability in absolute terms compared to their abducted peers, if Harvard’s selection process is at all effective. But they’d be the best relative to who was left. Correspondingly, would that reduced level of absolute learning mean that they wouldn’t receive the advantage that a Harvard degree confers in the labor market? Of course not. They would still be perceived as the cream of the crop relative to labor market peers. You sell your academic credentials in a market; their value is a function of their supply and their demand. We know that the college wage premium is to a large degree a simple function of the ratio between the number of jobs that require a college degree and the number of applicants who have one. The absolute learning represented by that degree is not the relevant criterion. The relevant criterion is the position of the student in the hierarchy, their relative performance.

I mentioned above that Black students, even Black students from low socioeconomic status (SES), have been improving steadily in absolute terms over time. What a Black third grader (or any third grader) can do today is head and shoulders above what one could do 30 years ago. But we still obsess over the racial achievement gap. Why? Because it’s relative performance that results in college acceptance and labor market improvements, not absolute, and white kids have been learning this whole time too, so the absolute gains of Black students don’t result in sufficient relative gains. When parents read their child’s state standardized test score results, are they doing so alongside a copy of the test or a detailed description of what the specific tested content was? No, because they don’t care. They care about how their kid performed compared to the other kids. When teenagers obsess over their SAT scores, they’re not motivated by their ability to answer reading comprehension questions correctly. They’re motivated by the fact that their SAT score percentile will have a meaningful impact on where they go to school, and how much they will eventually earn. This is the prioritization of the relative over the absolute, and it is foundational to our education system and our labor market.

Of course, changes to relative learning for any individual or subgroup require changes in absolute learning somewhere - you learn more or less than peers in an absolute sense and thus your relative position improves or declines. But it’s essential to understand that, for example, the pharmacy school graduates who emerged into a world where they suddenly had vastly more labor market competition didn’t know less than those who had the good fortune to graduate a decade earlier. They probably knew more. But that absolute learning was not relevant from a career perspective; their relative position next to thousands of other new graduates was.

Unfortunately, much of the educational discourse in our media fails to reflect this distinction. More unfortunately, while we can reliably prompt absolute learning gains in our students, we cannot reliably change their relative placement in the distribution, as I will demonstrate at length. Individual students appear to have some level of intrinsic ability that follows them throughout their academic lives, from kindergarten to college. I will rush to point out that this argument does not assert that the racial achievement gap is inherent. As I have argued repeatedly, it is perfectly consistent and in fact quite sensible to believe that the observed academic differences between individuals are partly because of intrinsic differences, whether genetic or not, while the differences between certain groups such as genders or races are purely environmental. See the jumping contest analogy here for a simple explanation. That is in fact what I believe - that within-group variation (differences between any individual kids, including within the same race) has an intrinsic component while the between-group variation between races is environmental.

While my great preference would be to use the term “educational mobility” to refer to the phenomenon I’m describing (the movement of any given student within an academic distribution or hierarchy), that term already belongs to the relationship between a child’s educational outcomes and that of their parents, or intergenerational mobility. (Which is, as a generic statement, rather low.) Of course, there is a relationship: low intergenerational mobility suggests lower movement in the peer hierarchy as well as in comparison to parents. If students are moving around a lot relative to peers, they must be moving relative to static parent outcomes. Regardless, I’ll try to avoid using the term “educational mobility” in this essay to limit confusion, unless I am specifically referring to intergenerational mobility.

We can express the static nature of relative educational outcomes quantitatively, in a variety of ways. The simplest is to observe that by far the most consistently effective predictor of future academic performance is prior performance. This paper summarizes the reality simply:

The present study shows that individual differences in educational achievement are highly stable across the years of compulsory schooling from primary through secondary school. Children who do well at the beginning of primary school also tend to do well at the end of compulsory education for much the same reasons.

This is the finding of all such research. At essentially any point along a given student’s educational journey you can take their outcomes relative to peers and enjoy strong predictive ability about their performance at later stages. (Past performance predicts future performance so well that it seems most education researchers don’t seem to think of it as a predictor at all.) If you’d like to go short-term, student performance in third grade predicts student performance in fifth grade very well, as you would imagine. If you prefer long-term, academic skills assessed the summer after kindergarten offer useful predictive information about academic outcomes throughout K-12 schooling and even into college. Similarly, third-grade reading group, a very coarsely gradated predictor, provides useful information about how well a student will be doing at the end of high school. The kids in the top reading group at age 8 are probably going to college. The kids in the bottom reading group probably aren’t. This offends people’s sense of freedom and justice, but it is the reality in which we live.

There’s even evidence that as students age the stability of their relative performance grows over time. In reading comprehension specifically, for example, “the strength of the relation between Reading Comprehension from grade to grade tended to increase over time.”

The persistence of relative academic performance is remarkable. Standardized test scores collected at the age of thirteen are strong predictors of not just future high school and college educational performance but adult outcomes like academic career milestones and economic position, even after adjusting for parental income:

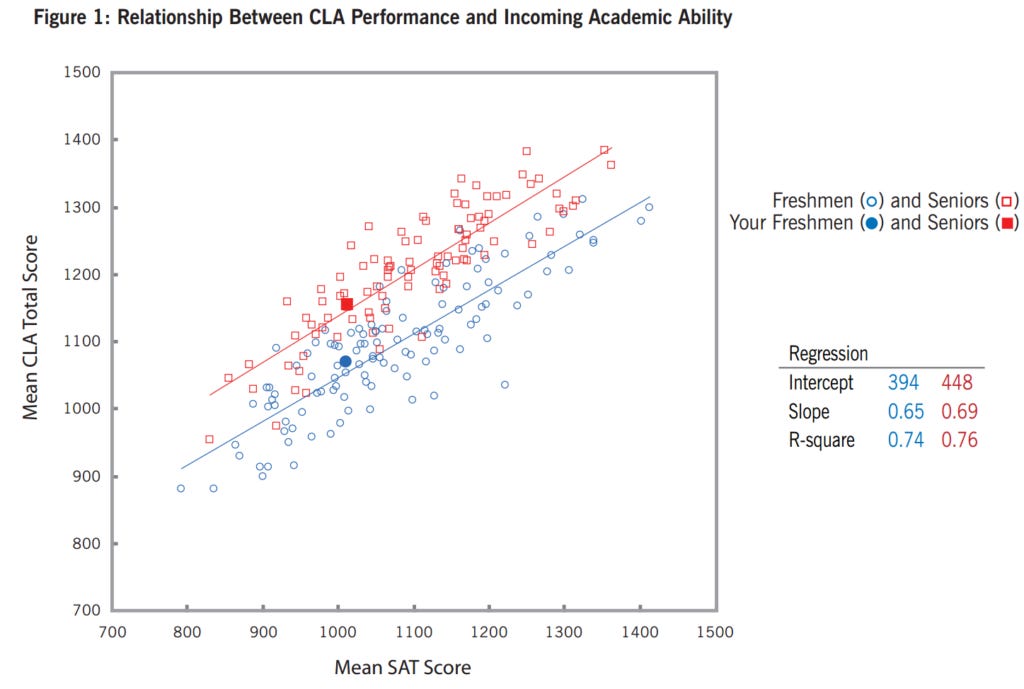

If you’re a college administrator, what is the best predictor of how your incoming freshman class will perform as college seniors on a standardized test of college learning? Their performance on the SAT as high school seniors, of course. What else? Here’s an elegant visual to demonstrate how all students can grow in absolute terms while staying in place in relative terms:

The distance between the blue and red regression lines represents absolute learning, how the students at the average college have improved over the course of their college careers in an absolute sense. The relationship between the variables, the tight grouping and angle of the data pattern shows that the relationship between the mean SAT score your students got near the end of high school and the mean Collegiate Learning Assessment score your students got near the end of college is quite strong. Similar relationships have been observed with other tests such as ETS’s Proficiency Profile. If your admissions process screened out weaker students coming in, your reward was stronger students going out. Obviously! Were individual student outcomes as elastic as people in the policy and politics world assume, you wouldn’t predict this kind of relationship. Students would go to different colleges and the supposedly-dominant environmental variables would overwhelm prior advantage and create very different relative performance outcomes. But that simply doesn’t happen. What, you think Harvard is going to risk its reputation on something as illusory and intangible as “school quality”? There's an endowment to grow!

If you’re an administrator at a college that’s not selective, you can take heart in the fact that even though your student body is likely on the lefthand side of the plot due to low incoming SAT scores, you can move your institutional average northwards over the course of a class’s career by producing absolute learning gains. Your students will leave knowing more than they did when they came in. But what you probably can’t do - what there’s simply no reason to believe you can do, really - is teach your students so well that they catch the student bodies of the schools on the right half of the plot. Because those students not only started out ahead, they’re learning at college too, inconveniently. There is no evidentiary basis for the conventional wisdom that schooling can change the performance of students relative to their peers, with any consistency at anything like scale - and it’s change at scale that would be required to “fix our education system.” Wonks should perhaps ask themselves why they believe otherwise.

For decades, researchers have tried to solve this conundrum, but there is little to show for it, and in fact as research methods have become more sophisticated the picture has only gotten more pessimistic. Nothing seems to work. A 2019 paper evaluated the most rigorous kind of education research we have, randomized controlled trials. The 141 studies considered in the paper had a mean effect size of .06 standard deviations. Not .6 - .06. Which is to say, the average RCT shows no practical significance at all. Consider this large meta-analysis of techniques attempting to help low-SES students succeed.

The dots are the mean weighted effect sizes of a given intervention. (Weighted by sample size, that is.) The red lines are the error bars, which help to tell you if the observed effect is statistically significant. If the red line crosses the vertical dotted line, we can’t say with statistical confidence that the effect is greater than zero - which means that of fourteen major studied interventions only six have statistically meaningful effects at all, and of those three are less than .2 of a standard deviation, which means they have limited practical effects. (Should we be funding small group tutoring? Yes!) You’ll get a better picture of how often education research fails to identify any meaningful effects from interventions by looking at a similar graph of the means and error bars of individual studies:

Some will argue that these plots are misleading and perhaps undersell the value of various interventions. But there’s no question that in study after study, for decade after decade, researchers have found that interventions presumed to have causal influence on educational outcomes simply don’t. Almost everything is clustered right around zero. Most things we try in education simply don’t do anything. This is reality. Bet on the null.

This has led to years and years of agonizing and wondering why. We’re swimming in examples of supposedly transformative educational ventures, most prominently in the realm of educational technology. (No coincidentally the site of a lot of profiteering.) Why have vast expenditures devoted to classroom technology so often had disappointing results? Why does randomly distributing computers for children to use at home make so little educational difference? Giving students free lunches is an absolute positive social good, but has negligible influence on student performance. There are many, many other cases where interventions that seem intuitively powerful turn out to have no or little effect in the real world. If you believe the standard liberal story of children as undifferentiated academic masses whose outcomes could be easily improved with a little want-to and ingenuity, this is perplexing. If you listen to research, experience, and common sense, you’d recognize that it’s precisely what you’d expect in a world where everyone is not equal in academic potential.

You might say “but most studies measure absolute learning, not relative.” But consistent absolute learning for the academically disadvantaged is the only tool through which relative changes could be achieved at scale, right? The poorly-performing students need to make absolute academic gains that the higher-performing students don’t. The problem is that if you found such a tool - if any of this worked - it would be hard to imagine that parents of high-performing kids would accept not allowing their children to take advantage of it too. (If you want to close the Black-white achievement gap, the most reliable way would be to outlaw white students from going to school for several generations.)

Consider the neoliberal obsession with school quality, expressed in support for vouchers and charter schools. If the environment dictated everything, then school quality would be immensely consequential. If school quality is a real, stable, and meaningful property, and the environmentalists are right about educational outcomes, then switching schools should have a dramatic effect on how a student performs in the classroom. But what parents typically find is that their child slots into the distribution just about where they were at the old school. The research record provides a great deal of evidence in this direction too.

Winning a lottery to attend a supposedly better school in Chicago makes no difference for educational outcomes. In New York? Makes no difference. What determines college completion rates, high school quality? No, that makes no difference; what matters is “pre-entry ability.” How about private vs. public schools? Corrected for underlying demographic differences, it makes no difference. (Private school voucher programs have tended to yield disastrous research results.) Parents in many cities are obsessive about getting their kids into competitive exam high schools, but when you adjust for differences in ability, attending them makes no difference. The kids who just missed the cut score and the kids who just beat it have very similar underlying ability and so it should not surprise us in the least that they have very similar outcomes, despite going to very different schools. (The perception that these schools matter is based on exactly the same bad logic that Harvard benefits from.) Similarly, highly sought-after government schools in Kenya make no difference. Winning the lottery to choose your middle school in China? Makes no difference. What about the highly-touted charter school advantage? I have argued that it’s in effect a shell game of nonrandom “random” lotteries here, and even if we take the research record at face value we’re still looking at small effect sizes, especially given all the hype.

All of this confirms anecdotal experiences. Did kids you know go from failures to whiz kids when they moved to a different state, a drastic change in environment? Does sending a kid to private school solve all of that kid’s educational problems? Do Montessori principles ensure that even severely struggling children can succeed? No, of course not. Because they’re the same kids. Why doesn’t this simple wisdom penetrate policy and politics?

Teacher quality perhaps exists but likely exerts far less influence than generally believed. There is no such entity as “school quality.” The concept is an illusion. There is the underlying ability of the students in a school that produces metrics that we then pretend say something of meaning about the school itself. That’s it.

Consider common complaints about screening effects - that is, that policies like public school districting cause educational inequality by keeping students out of better schools. These arguments typically confuse cause and effect. Zoning doesn’t make kids perform poorly by keeping them out of the best schools. Zoning creates the impression of the “best schools” by keeping out the kids destined to perform poorly. Look at France. Late last century France ended conscription for young men so that more of them could attend college. Given France’s historical problems with persistent unemployment, the government hoped this would have economic benefits. Academic high-achievers had already been able to secure a release from such duty to attend college, but other young men were compelled into service. The result of ending the practice based on a specific birthdate was a sudden influx of students into higher education and a kind of natural experiment thanks to the cutpoint. A population of men who would have spent years in the military instead spent them going to school. But it not only made no difference in terms of wages or employment, it made almost no difference in the number of people graduating from higher education. Conscription had been screening out the marginal students from attending higher education, true. But removing the screen didn’t make those students any less marginal. At a vast scale, in one of the wealthiest and most developed countries on earth, giving more students the opportunity to attend higher education where they were previously screened out simply made no difference.

Meanwhile constantly cited explanatory mechanisms, like class size, aren’t really explanatory at all. Calls for smaller class sizes are ubiquitous because they’re one of the few interventions endorsed by both neoliberal ed reformers and the teacher unions who are their enemies. But while quantitative effects of class size have been a research obsession for at least 40 years, there’s no real consensus on what exactly works, for which students, in which contexts. Claims of a small class size advantage routinely carry extensive lists of provisos, such as saying that it’s necessary for physical classroom space to not shrink along with number of students, the kind of requirement that makes implementing these efforts at scale a policy nightmare. And I would argue the research is discouraging anyway.

The famous Tennessee Project STAR study from the mid-80s helped set the national conventional wisdom that class size has a major impact on student performance. But the STAR study 1) only placed students aged 5 to 8 in smaller classes, particularly troublesome because environmental impacts on academic outcomes of children tend to fade over time, 2) was conducted in a state that was a significant negative outlier in all manner of educational metrics, undermining our confidence that its results could be generalized, and 3) has met with consistent skepticism about its randomization processes. And were the findings really so positive? Teacher-quality advocates Steven Rishkin and Eric Hanushek pointed out in 2006 that only 40 of the 79 small-size kindergarten classes outperformed the regular classes at all. A ten-year follow-up, again represented as a victory for small class sizes, found a significant increase in passing the state standardized language arts test for 8th-grade students who had attended small classes - statistically significant, that is. The advantage of those who had attended small classes earlier compared to those who had not was 52.9% to 49.1%. I will leave it to you to decide if that is practically meaningful. Either way, we’re left to figure out whether these results are large, consistent, and scalable enough to be worth the enormous additional expenditures this type of intervention would require at the national level.

It’s also perfectly easy to find studies that find that class size advantages are not remotely efficient given the associated expense or which find no meaningful small class size advantage at all. In 1995 Karen Akerhielm found performance boosts from reducing class sizes… by 10 students, a decrease with a financially massive cost at scale… of 5%… and only in history and science. In 2000 Stanford’s Caroline Hoxby found no statistically meaningful effect at all. Sathish Kumar does me a solid by providing a scatterplot in his 2019 study on student performance predictors:

Nor is there consistency between different studied groups; for example, at the university level, class size effects vary wildly depending on which students you’re looking at.

Again, if environment matters most or is all that matters, we would absolutely expect a major and consistent effect from class size. If intrinsic ability predominates we wouldn’t. Where is the evidence pointing? The constant churn of new conventional wisdom about this topic over the decades is not encouraging. Should we have smaller class sizes? I believe you can make a strong argument for that, yes. But the argument is that we should have smaller class sizes for the comfort of students and parents and superior working conditions for teachers, not because of uncertain benefits in quantitative metrics.

How about peer effects, the influence of learning alongside higher or lower performing students? Like class size, this factor is often cited as having a causative impact on education, but the evidence is slight. A large study looking at exam schools in New York and Boston - that is, selective public high schools in large urban districts - found that even though enrolling in these institutions dramatically increased the average academic performance of peers (thanks to the screening process to get in), the impact on relative performance was essentially nil. This was true in terms of test metrics like the PSAT, SAT, and AP Scores, and in terms of college outcomes after graduation. A study among students transitioning from the primary school level to the secondary school level in England, where dramatic changes occur in peer-group composition, found a significant but very small effect from peer group in quantitative indicators. Like, really small. It just doesn’t appear to matter.

The lack of class size and peer effects are just two of many dogs that don’t bark, intuitive explanations of academic outcomes that don’t actually work out. Another is grit, or a student’s capacity for perseverance in the face of challenge, which an 88-sample, ~65,000 subject meta-analysis finds is vastly less important than sometimes suggested in the media. (There’s an awful lot more grit skepticism out there if you’d care to look, and it’s not even clear if grit can be learned.) If you want your child to succeed in school and you can choose to give them more grit or a higher IQ you’d go with IQ 100 times out of 100. “Smaller classes give teachers more time to devote attention to individual students and thus improve performance,” “peers matter for how much a child learns,” and “it’s academically important to have perseverance and work ethic” are deeply intuitive stories about education that may be true in a broader sense. But the notion that they will reliably improve quantitative educational metrics is demonstrably false. Why? Because they’re premised on the notion that the relative outcomes of individual students are deeply malleable.

Merit pay and more stringent teacher evaluation were sold hard as the solution to our educational woes (or “woes”) and enjoyed the muscle of the federal government at their backs. But the actual implementation of these programs proved to be disastrous. The results of evaluations were frequently incoherent, with teachers scoring the highest one semester and the lowest the next, or getting great results for their Period A class but awful results for their Period B class. And principals frequently hated these schemes, as the outcomes on such quantitative metrics so often clashed with their own perception of which teachers were most worthy. Recent research is profoundly discouraging.

Federal incentives and requirements under the Obama administration spurred states to adopt major reforms to their teacher evaluation systems. We examine the effects of these reforms on student achievement and attainment at a national scale by exploiting the staggered timing of implementation across states. We find precisely estimated null effects, on average, that rule out impacts as small as 0.015 standard deviation for achievement and 1 percentage point for high school graduation and college enrollment. We also find little evidence that the effect of teacher evaluation reforms varied by system design rigor, specific design features or student and district characteristics.

It’s not just that the evaluation systems don’t reliably produce better outcomes. The value-added models themselves have been subject to sustained critiques, such as in the paper that demonstrated that “the standard deviation of teacher effects on height is nearly as large as that for math and reading achievement, raising obvious questions about validity.”

Nor does pre-K, the most commonly cited cure-all for educational inequality, seem to have much effect, although as you’d imagine the topic is very contentious. There’s been a lot of positive findings in this space that have then been challenged or walked back. For example, the well-known Campbell et al Science article looking at the health improvements (and knock-on effects) from early child care programs found robust gains, and this was reported all over the place. Unfortunately, this finding was severely undermined by the immense attrition of the sample (40% of males!), a problem that could not have been identified in the original paper because the information necessary to know literally wasn’t published there. To me, it screams of optimism bias in this type of research. I’m not accusing anyone of deliberate research fraud. I am saying that people who research pre-K programs tend to have a great deal of personal investment in their efficacy, and this unconscious bias inevitably colors the research. And it’s not like what’s actually in the research record is so great anyway. In fact, it’s gotten worse over time. Duncan and Magnuson, 2013:

(Why would the reported effects of pre-K programs shrink over time this way? Because we got better at doing studies.)

We have very recent evidence in this regard in the form of a paper in the journal Developmental Psychology. It’s a pre-K study that has many virtues, including a large n, genuine random assignment, and a longitudinal component, and it says kids who were assigned to the pre-K condition actually did worse than kids who were not. This paper is particularly discouraging for advocates, who tend to say that pre-K has non-academic benefits when academic results are discouraging, as it also shows pre-K students as having worse attendance and disciplinary outcomes. Afterschool programs? Sadly, no. Pretty unambiguous returns from several large-n studies performed fairly recently.

Education is of course a highly political issue, and one of the most common arguments in this domain is that educational differences are the product of socioeconomic status, that socioeconomic status is causative of academic performance, that these static student outcomes are the product of America’s high-income inequality and relatively high child poverty. Unfortunately, liberals tend to vastly overstate the impact of socioeconomic status on educational metrics. Yes, a generic SES effect exists in K-12, but it varies widely from context to context, and it does not have anything like the explanatory power some liberals assign to it, given that they speak as though it explains essentially all of the variation. Nor do dramatic changes in a family’s wealth seem to have much measurable impact on the outcomes of individual children within those families.

College attendance is undoubtedly influenced by SES, but it’s unclear how much of this is through the educational mechanism itself. Claims that the SATs merely replicate the income distribution float around social media constantly, but it’s very easy to produce a correlation coefficient that shows the relationship between the variables of SES and SAT score. And a ~150,000 score sample shows an r-squared of .0625 - that is, less than 7% of the variation in SAT scores is explainable via family income. Is that number meaningful? Sure. It’s not nothing. But it means that the large majority of the variance is not explainable by SES. Meanwhile, the most regularly cited reason that better SES would raise SAT scores, test prep, does not have a strong evidentiary basis in the research record. I regularly encounter pushback on this issue, but the data seems fairly clear to me: Powers & Rock 1999, Briggs 2001, McGahie et al 2004, Griffin el al 2008…. All show little or no effect on the outcomes of standardized tests from coaching. The story liberals want to tell about the SAT and similar tests is a mirage.

It’s also common to speak imprecisely about differences in the SES status of families vs the expenditures of the schools that serve those families, and assumptions about which schools have greater financial resources are frequently incorrect. (For the record, high-poverty and high-racial minority schools actually receive significantly more per-pupil than whiter and more affluent schools, but there is a lot of complication there.) Peer and neighborhood effects are frequently endorsed as explanatory, but they don’t tell us much of what we want to know. An analysis considering segregation, neighborhood effects, and the SES of schoolmates still left 90% of the racial achievement gap unexplained, suggesting that these factors have limited salience for any population of students.

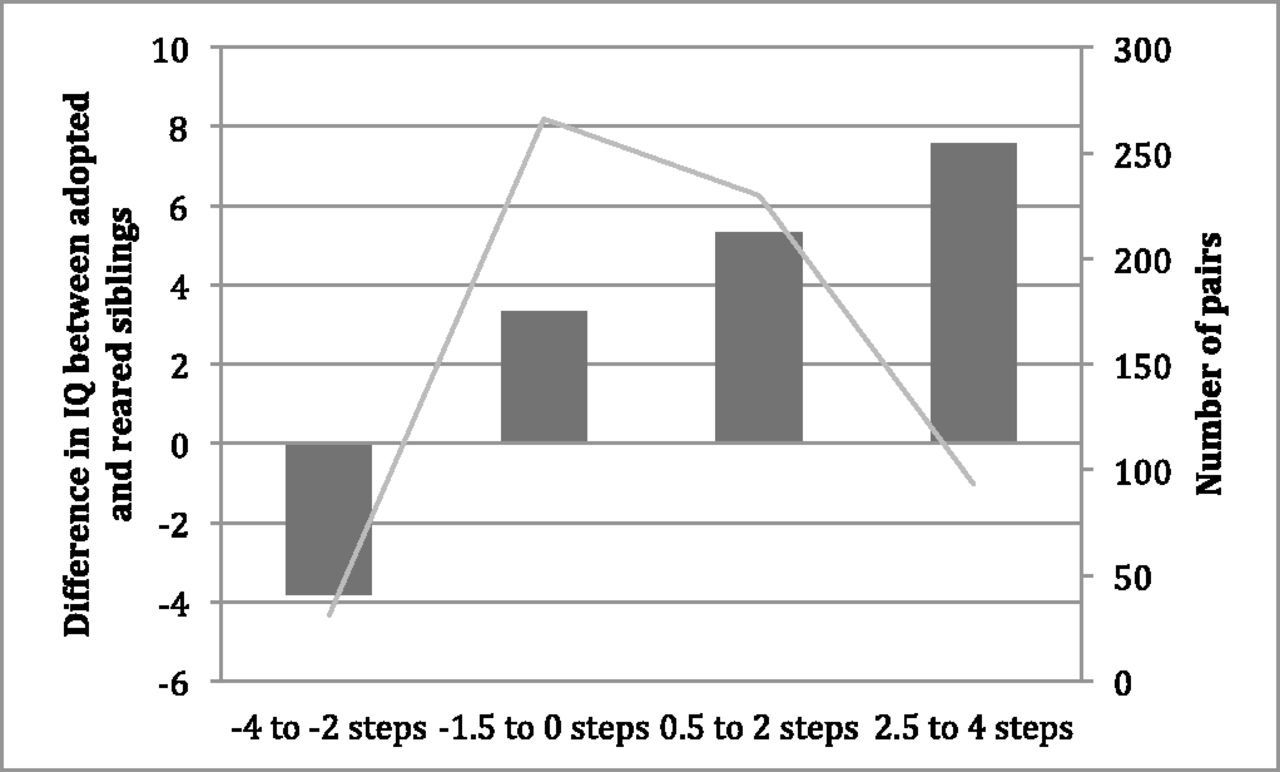

I have largely avoided using IQ as a metric in this piece, as IQ is dismissed by many. But IQ is, if nothing else, highly correlated (by social science standards) with school performance, and it’s worth mentioning the following study because it considers perhaps the most radical environmental intervention we can imagine, adoption. In 2015 Eric Turkheimer looked at pairs of Swedish siblings who were raised in different home environments to determine the influence of parent education (a strong proxy for income as well) on IQ.

Turkheimer argues that this demonstrates a strong effect from being reared by parents with significantly greater education. But the chart can be a little misleading if you don’t apprehend the scale of the Y-axis. The difference between 0 step-ups and the largest step-up is 7 points of IQ. 7 points is not nothing, and is consistent with a belief is that there is some environmental impacts on academic and cognitive outcomes. But 7 points is less than one-half of a standard deviation in IQ. Moreover, consider what it means that the massive environmental difference of being raised in different families can only muster that much effect, and that of course placing students into an entirely different familial environment is not a remotely practical means of fixing things. Meanwhile, the Wilson effect suggests that the importance of the family environment on cognitive outcomes fades over the course of childhood.

The left further claims that a robust social democratic state could ameliorate these problems and create educational equality. But as I’ve discussed in the past, Denmark’s vastly more redistributive social state, far lower poverty, and lower socioeconomic inequality than the United States do not result in any greater intergenerational educational mobility at all. It’s true that intergenerational mobility is not the same as the type of movement in relative measures I’m talking about, but as I suggested above since parent and child are correlated in educational outcomes for both any individual student and their peers a lack of movement in intergenerational mobility would suggest a lack of movement compared to peers also. And the bigger question looms: if everything Denmark is doing to influence the environment of its citizens has such little impact on their educational outcomes, what more could we realistically do?

Is my claim here that environmental factors don’t contribute at all to educational outcomes? No. There are consistent and demonstrable impacts from various influences that might be considered environmental. For example, premature and low birth weight babies frequently go on to struggle academically as older children. The negative cognitive effects of lead have perhaps been somewhat overstated but are nonetheless real. Access to legal marijuana does negatively impact the academic performance of college students, though by less than a tenth of a standard deviation. There are of course others, and the aggregate of many small environmental influences can be meaningful. I’ve said many times that I believe the racial achievement gap is likely the product of the profoundly different environments Black children live in on average, and these environmental changes are far more complex and multivariate than the SES differences that do not adequately explain the achievement gap. The problem is that it’s far harder for policy to change a vast number of tiny influences than to change one big influence. Nor is there any guarantee that any given environmental influence can be changed. As neonatal medicine becomes more advanced we will have more surviving preemies, not fewer; we could do a massive lead cleanup, but the political barriers are significant for debatable gain; we are deciding as a culture that the costs of criminalizing marijuana are higher than the benefits of doing so; etc. Environmental does not necessarily mean malleable!

And, yes, to repeat myself, absolute learning can happen. Formal education in and of itself does have durable and real improvements to intelligence. (The child care function of public schooling has also been transformative and progressive.) Doesn’t that disprove the point of this piece? Look at learning loss from Covid. Doesn’t that prove education works? Not in the sense I mean, no. Again, the question is not whether schooling helps individuals gain absolute knowledge or skills, but whether it can close relative gaps. If school works generically well across ability levels, it can’t. Formal education has real benefits. The trouble is that most everybody goes to school and enjoys those benefits, so the power of schooling to establish durable changes in relative position on the ability spectrum is limited. (And lower-performing people self-select out of higher education, which accelerates their being left behind.) Compulsory education is a double-edged sword if you’re interested in shaking up who’s on top and who’s on the bottom. As I suggested above, if you were really maniacally focused on closing relative gaps, you’d just prevent the higher achievers from attending school at all.

All of this suggests that there is something innate or inherent to academic ability. (Which again does not necessarily imply that this factor is genetic.) Many will reply to this essay by saying that just because something is innate does not mean that it is unchangeable. This is true, and I haven’t and wouldn’t say educational outcomes are permanently immutable. The question is, what can we do from the perspective of the system that would work to “fix our schools,” to achieve the (remarkably vague) education-driven social outcomes politicians and policy types want? How would we close the gaps?

The kind of intervention we would need has to

Have a meaningful influence on academic outcomes where so many others have failed

Be reliable, replicable, and scalable to a vast degree

Cost little enough that the administration of this intervention is economically and politically feasible

Somehow apply only to the students who are struggling or any subset thereof, and not to the students who are already flourishing, or else allow for us to prevent the parents of flourishing students from accessing this intervention for their own kids, lest we merely advance the whole student population forward but preserve the current relative distribution that determines professional and monetary rewards under meritocracy.

Simple.

I quote James Heckman, the same James Heckman who co-authored the Denmark paper and the problematic pre-K health outcomes paper. Ten years ago he wrote

Gaps arise early and persist. Schools do little to budge these gaps even though the [perceived -ed.] quality of schooling attended varies greatly across social classes…. Gaps in test scores classified by social and economic status of the family emerge at early ages, before schooling starts, and they persist. Similar gaps emerge and persist in indices of soft skills classified by social and economic status. Again, schooling does little to widen or narrow these gaps.

I would argue that, in the years since, the evidence that academic hierarchies are essentially static has only grown.

I will not attempt to spell out the political and policy repercussions of this reality here. The Cult of Smart is a book-length version of this argument that includes long sections describing both more practical educational reforms and broader society-level changes that could better protect those who are on the bottom of the academic performance spectrum. You may disagree with some or all of those proposals as you like. But they are an honest attempt to wrestle with a basic reality of education and society that politicians and wonks are not allowed to address plainly because of misguided fears about the consequences of this thinking. The evidence is clear: immense efforts in educational interventions have utterly failed to close performance gaps, and vast expenditures in education have failed to close socioeconomic gaps. It’s time to try dramatically different approaches, and it’s time to demand that people in the policy world accept reality.

Education is a good in and of itself, but the impact of education on the economy will always be most salient in political debates. By some metrics, the fastest-growing occupation in America is not programmer or microbiologist but home health aid. The job doesn’t require a college education. The median wage is $27,000 a year. Our system’s message to all of those people who will spend their days helping keep our elderly alive for poverty wages is, well, hey. Should have done better in school. Maybe the first step in doing better for them is recognizing that most of them never had a choice. But if you’re really dead set on education as the key to improving the economic fortunes of the disadvantaged, and you don’t think we can or should redistribute our way to a more just and equal society, and you’re fixated on moving kids from the bottom of the academic performance spectrum to the top, what can we do? What works?

Nothing.

I agree strongly with this essay, based on my experiences growing up in a rural, working-class community, where I was one of the very few students whose parents had gone to college, let alone graduate school, and where only about a dozen students out of a graduating class of 650 went to selective colleges (more students went into the military than to college).

A significant problem with educational policy is that people who set the policies didn't attend public schools like mine. They tend to come from elite educational backgrounds and the professional managerial class, and very few of them have direct personal experience with people who are bad at and don't like school. So they think that all students will be like they were and will succeed at school, if we just have high expectations for kids and do this new and fashionable intervention (whatever it may be this time).

It doesn't work that way. I think we need a system like the have in Europe, and yes, I'm talking about tracking students into academic and vocational tracks. I'm old enough to have gone to school when tracking was still done, and it made a huge difference not just for me, but for students who struggled in school. Based on my experience, and pace claims from the experts that stronger students will buoy up the weaker ones by tutoring and challenging them, the weaker students didn't learn or enjoy the academic classes; instead they would pressure the stronger students to help them cheat, or would rely on the stronger students to do all the work in group projects. My high school allowed students to leave campus for classes at the local vocational school and to work at jobs, and the students who participated in these programs enjoyed them and got a lot more out of them than they did from the academic classes.

I believe that the most humane system allows every student to discover his or her interests and talents and receive an appropriate education for those interests and talents. I am grateful that this position has as eloquent and convincing an advocate as you, Freddie.

"This is the prioritization of the relative over the absolute, and it is foundational to our education system and our labor market."

This, for me, is the crux of the issue. It doesn't matter if an individual gets a higher score on an IQ test compared to previous generations, what matters is where they place relative to their peers right now. Given two candidates for a high paying position in tech or finance who is going to get the job offer? The individual with an average IQ or the really bright one? Labor markets are competitive. In the end it doesn't matter how much an individual's educational attainment has improved if he is still relatively less qualified than the next guy in the interview.

There is nothing inherently wrong with sorting based on intellectual ability in the labor market. Who doesn't want a smarter doctor? But society goes off the rails when it sniffs in disdain at manual labor, dismissed it as "unworthy" and therefore implicitly condones condemning an entire segment of the population to a lifetime of drastically lower wages.

To be clear I don't think there is anything inherently wrong with physicians making more than fast food workers but there are extremes. When we talk about a country where the federal government pumps billions of dollars into higher education while leaving vocational and technical schools to starve we are talking about a country where the class of the college educated has seized the reins of power and are busily engaged in securing their economic advantage. Consider this: workers without a college degree live shorter lies and earn far less than the college educated. Why should they be the ones on the hook for forgiving college tuition debt?