Funding Gaps Cannot Explain Academic Gaps

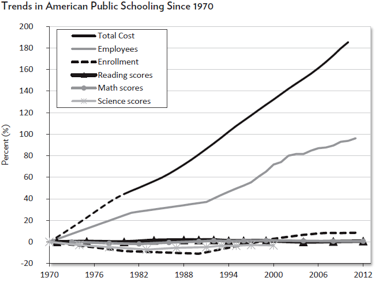

we've been throwing money at our problems for 40+ years

Do school expenditures determine student performance? Are our educational gaps resource gaps? I would have thought that I could confidently answer with a no and not be challenged, at this point. People have regressed spending by countries, states, and districts on outcome metrics for a long time, and they pretty much universally show that there is no relationship between spending and success as defined in traditional terms. Neither countries that spend more nor states that spend more consistently outperform their stingier counterparts. We haven’t been able to make real causal statements, but in education we almost never can, nor is it easy to do so at the scales we’re talking about here. Perhaps the most commonly-cited review comes from the Hoover Institution’s Eric Hanushek1, who is a zealous advocate of teacher quality measures (and their nastier consequences) and who since the 1980s has been a loud voice saying that we can’t spend our way out of our problems. In the intervening decades this view has become the conventional wisdom. But lately, there’s been a growing sense that it’s wrong.

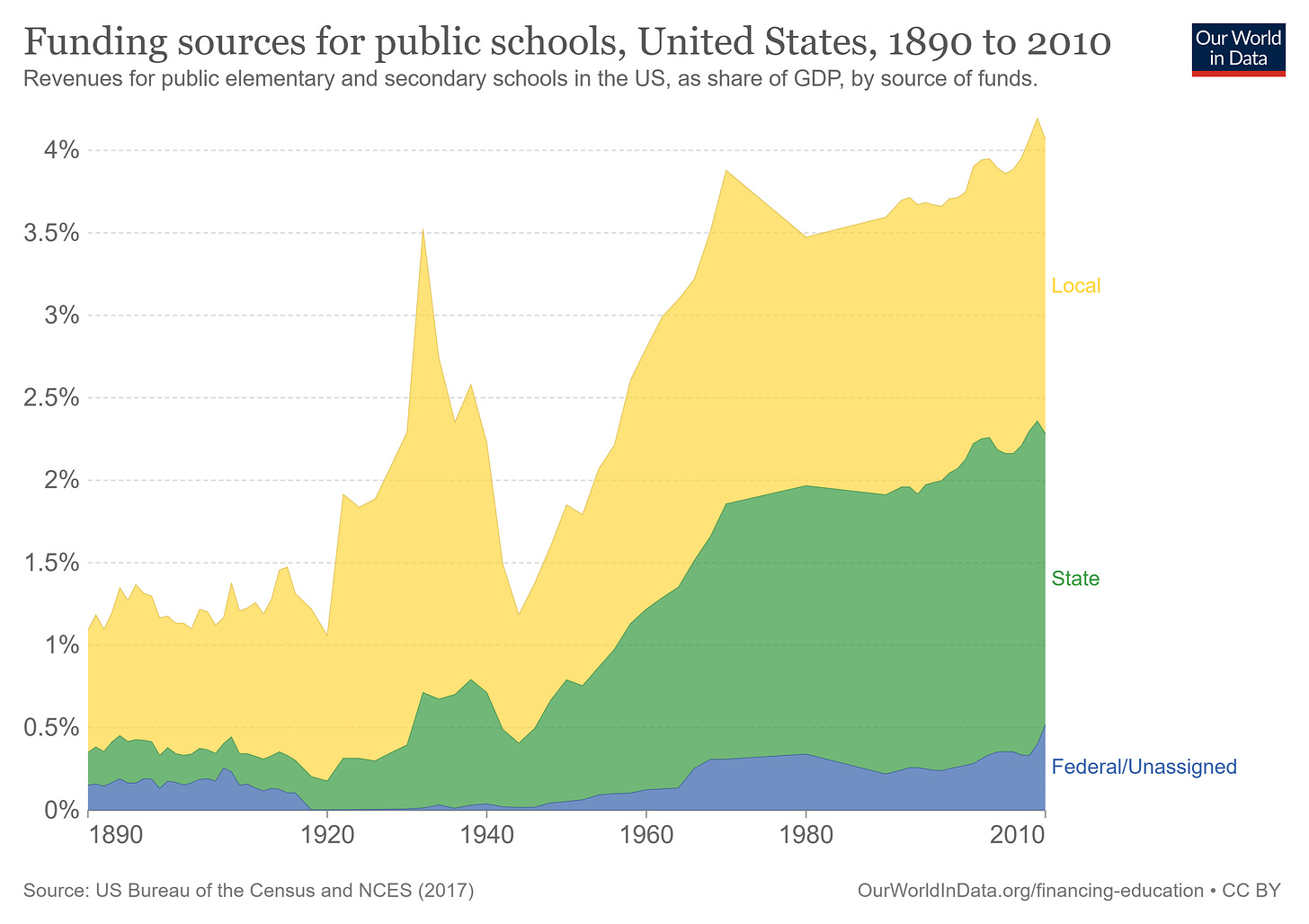

I doubt that anyone would object to the claim that the United States has been trying to spend its way out of educational inequality for decades. Though you sometimes hear, absurdly, that we are “defunding” education, we are spending as much as we ever have, in inflation-adjusted dollars, and that is significantly more than we spent for the great bulk of the history of public education. And this funding increase has been steered in dominant majorities towards “need,” which means poorer schools and disproportionately higher-minority schools1. It’s typical for left-leaning people to lament that poor districts are broadly underfunded relative to others, but it’s hard to justify this belief. Part of the perception problem is that people are operating in a local-spending dominant mindset, when that reality doesn’t really exist anymore.

The growth of state spending has been a quiet but major story in recent decades, in part due to the massive expenditures necessitated by NCLB and ESSA testing requirements. State funding sources are now at parity with local sources and while federal education spending is still far behind, that expense has grown to something like .5% of GDP. Discretionary fed money tends to be heavily concentrated in the worst-performing schools, and state expenditures also are often steered towards struggling schools and districts. Here’s Title I spending as a convenient indicator of the larger dynamic, again old data but the trend hasn’t changed.

We’re spending more, and we’re steering the money where people say they want it to go. It just hasn’t worked.

I really need to underline this point: lower educational expenditures per student can’t be the source of race and income gaps because Blacker and poorer schools receive more per-pupil funding than whiter and richer schools. Sosina and Weathers 2019: “On average, both Black and Latinx total per pupil expenditures exceed White total per pupil expenditures by $229.53 and $126.15, respectively.” Check the tables in the study for more. And this does not encompass the small but growing amount of private dollars that are finding their way into public schools through various grant programs and foundation spending, which likely almost all goes to struggling poor and high-minority schools. This finding flies so directly in the face of the progressive conversation that I find people just can’t hear it, but it actually makes perfect sense. Of course those schools have more funding; we’ve been throwing money at our achievement gaps for 40 years.

(I also urge you to investigate special education funding if you are interested in these topics, as special ed tends to be hideously expensive and devoted to children who have unique difficulties in meeting standards.)

Combine this with the widespread sense that these costs haven’t resulted in better schools and you get some understandable bipartisan exasperation. Frustration about our “failing” schools is potentially misleading; we are arguably one of the best school systems in the world when you match for relevant demographic data in PISA scores, and our median and top 5% of students are competitive with anywhere else in the world. We suffer from truly terrible performance in our bottom quintile which drags our overall numbers way down. But that quintile exists, and it’s the case that we have large and troubling gaps and haven’t closed them despite it being a policy obsession since before I was born. We’ve burned money on it and gotten nowhere. It’s not hard to understand why people conclude that money doesn’t seem to matter much.

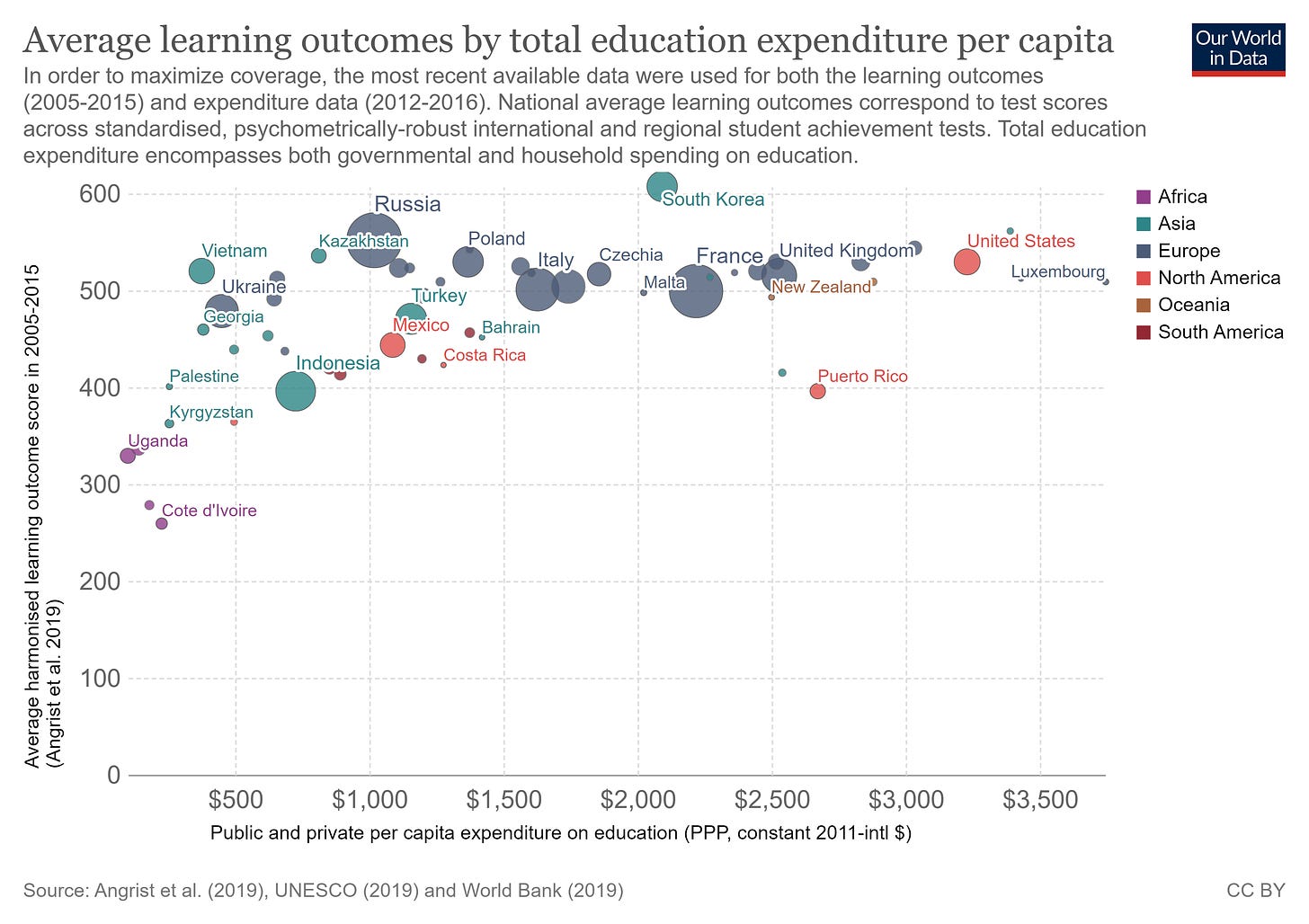

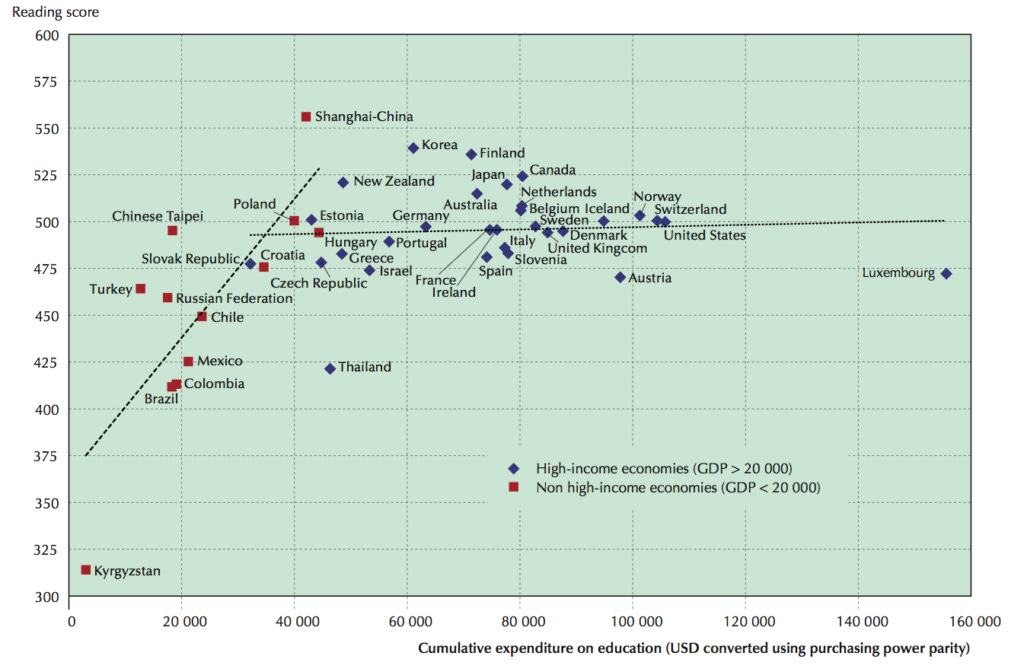

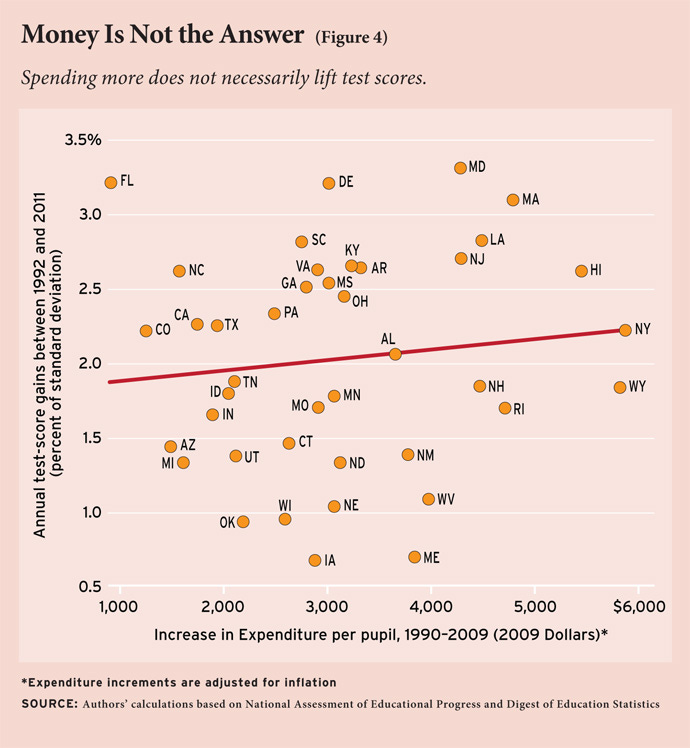

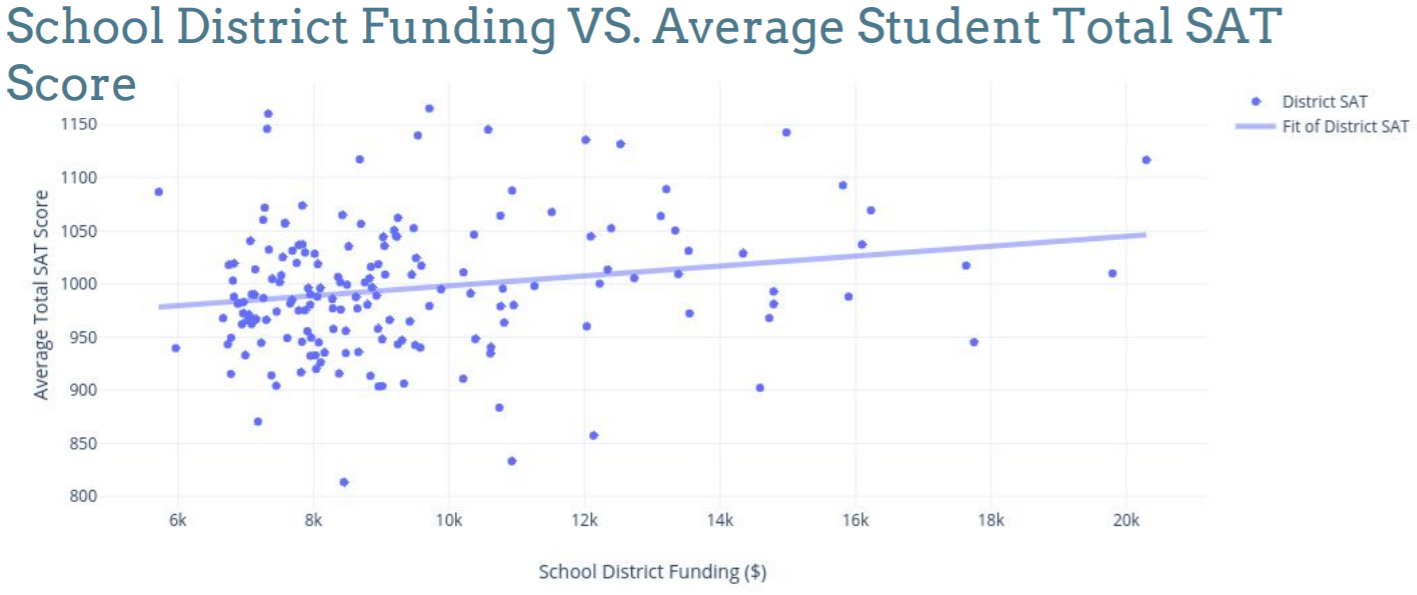

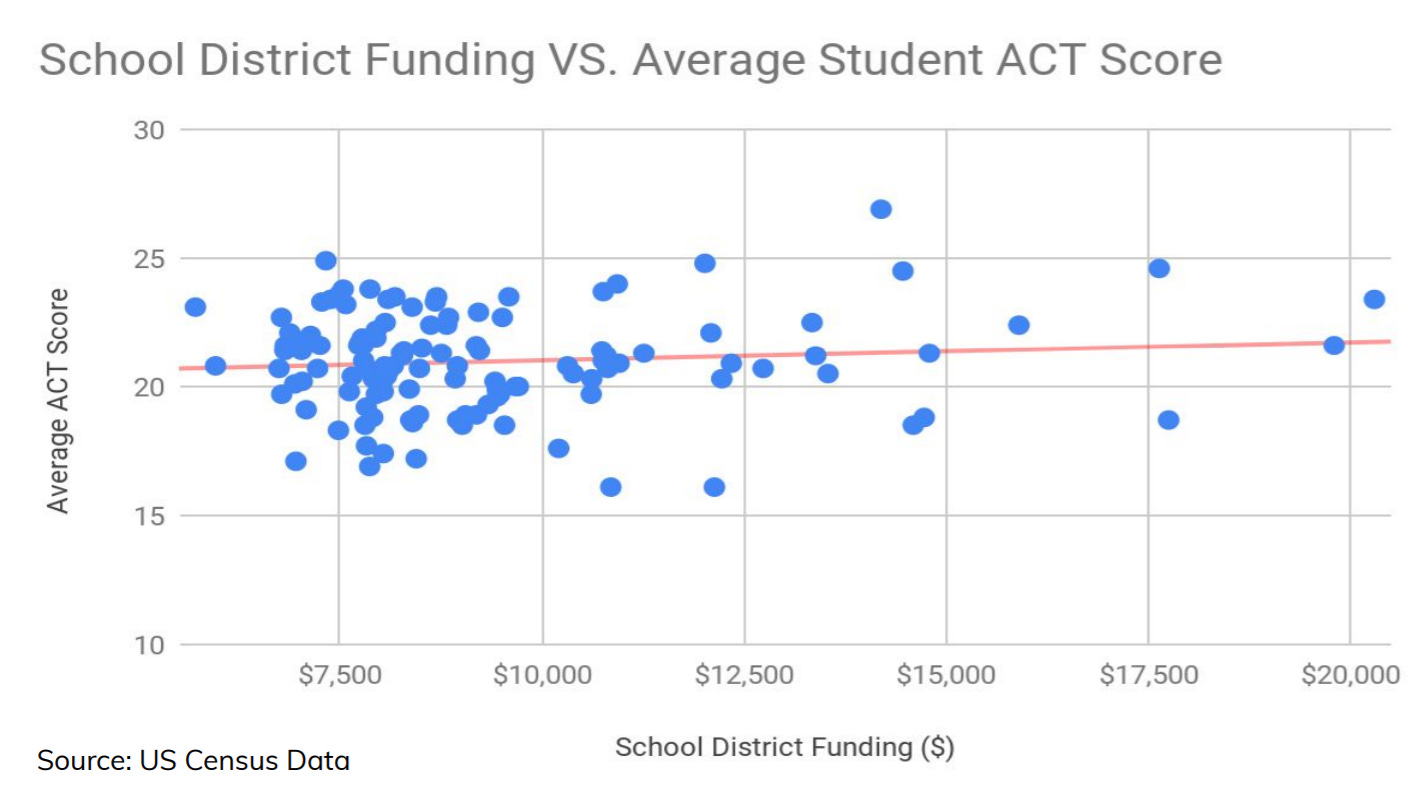

This point has frequently been argued through scatterplots, not unreasonably given how consistently they show little or no relationship.

There’s a relationship but the overall line is remarkably flat. The trend that exists is largely a product of outliers where truly poor countries have truly bad results; among developed nations there’s simply no trend. Poorer countries like the Ivory Coast, Uganda, Kyrgyzstan, Indonesia and Mexico would seem to suggest a relationship, but developed countries show no such thing. The USA spends something like 8 times what Vietnam spends per student and performs just about exactly as well, while Luxemburg spends more than anyone else in the world and performs worse. Is there a visualization to help with this? Yes indeed; different Y-axis variable but same overall dynamics:

I find this intuitively understandable; the poorest countries lack the ability to consistently house students in minimal comfort and to provide them with even the most basic learning materials. But past a certain level of spending the returns diminish and the power of money runs up against its limits. How about between states, though?

Not much. Also DC is a great sadness and would bend out whatever relationship is there if we don’t drop it as an outlier, which we probably should. Middle-of-the-pack performer Utah spends less than anybody; barely-better New York spends profligately. How about changes over time?

NAEP gains on spending increases rather than raw scores on raw spending. Still a lot of nothing. School districts? Here’s some plots, which have the added virtue of avoiding the NAEP so we don’t fixate too much on one DV.

Nothing and really nothing. Same concepts as above, different visualization:

So you’d think this would be pretty damning. But more and more often I read people questioning this conventional wisdom. I’ll use this post from Dave Evans of the World Bank as a jumping off point. Evans reports that in recent years researchers have undertaken causal studies that supposedly show that expenditures matter a great deal. Evans argues that the scatterplot data is not dispositive. As he correctly says, this is all correlative. Against it he advances several newer studies that purport to find significant effects from increased spending. Evans uses the word “causal” to refer to a quasi-experimental design and a design utilizing quasi-random sorting, which makes my trick knee act up, but I will leave the causality wars to others and as usual my commenters will pick apart the methodologies.

My intent is not to critique either paper, but rather to offer what to me seems like some serious problems we might have interpreting them from a policy standpoint. For now I will take their findings as given: despite the historical failure of spending or spending increases to result in proportional improvements in educational metrics, there is a causal relationship between higher spending and greater performance.

Which is not necessarily a contradiction. Causation does not erase the influence of correlates. For example, all manner of causal variables related to disease are not correlated with infection rates compared across countries because of different levels of sophistication of medical science and other variables. (Hepatitis C causes liver cancer, but not among those who have access to the pricy new medications, which means that as those medicines become more widely available the correlation between Hep C and liver cancer will be reduced.) But this leaves Evans et al. with a pretty glaring question staring them in the face: if school spending leads to student learning… why isn’t school spending leading to student learning? As far as I’m aware not even these researchers dispute the headline national numbers, which show ever-increasing resources spent on schools and nothing to show for it in comparative educational measures. The obvious assumption is that there must be some unexamined variable that is acting as a headwind on the power of additional resources to improve outcomes. But… what?

To my frustration…

Neither Evans nor either paper offers a plausible mechanism that could explain the failure of large-scale funding differences to produce the educational gains their research suggests we should observe. If spending more does produce learning gains, why does Vietnam perform as well as the United States? Why does Colorado get equal performance for a small fraction of New York’s costs?

Neither Evans nor either paper estimates a threshold of spending past which point student achievement should actually be expected to rise in contradiction with the historical trend, or alternatively, where returns start to diminish.

Neither Evans nor either paper can explain what aspects of higher spending actually provide efficient returns, or what this causal relationship actually looks like in simple real-world terms, although Jackson offers useful supposition.

Evans and Jackson both stress that how you spend the money matters. For that matter, Hanushek himself has conceded that targeted strategic spending could move the needle. The problem is that, despite decades of data from armies of researchers, no one really knows what kind of spending actually is strategic2, and the question is so inherently political and contested that it’s hard to imagine a scenario where some sort of useful best practices emerges, especially given that you can make ed data say what you want it to if you try hard enough. I don’t know anyone who says that money never matters or that there aren’t scenarios in which more spending would help. The problem is that we’re talking about big ungainly bureaucracies (yes, even in charter contexts) that have a vast number of gatekeepers and influences, making efficient spending difficult, especially considering that different students have different needs, and we have a profound dearth of compelling evidence for how to spend even if we could do so nimbly. Remember, small effect sizes, huge variances, no or questionable randomization….

Personally, I’m affronted by the fact that there are American schools that, thanks to faddishness and the influence of profiteering, have state-of-the-art computer classrooms but rotting walls full of asbestos. (This school district spent more than a billion dollars on iPads.) To repeat a mantra, the first priority is to make sure that schools are warm, safe, nourishing spaces for children, before we start to worry about quantifying learning at all. But can I prove that my intuitive priorities align with what would raise test scores? I cannot.

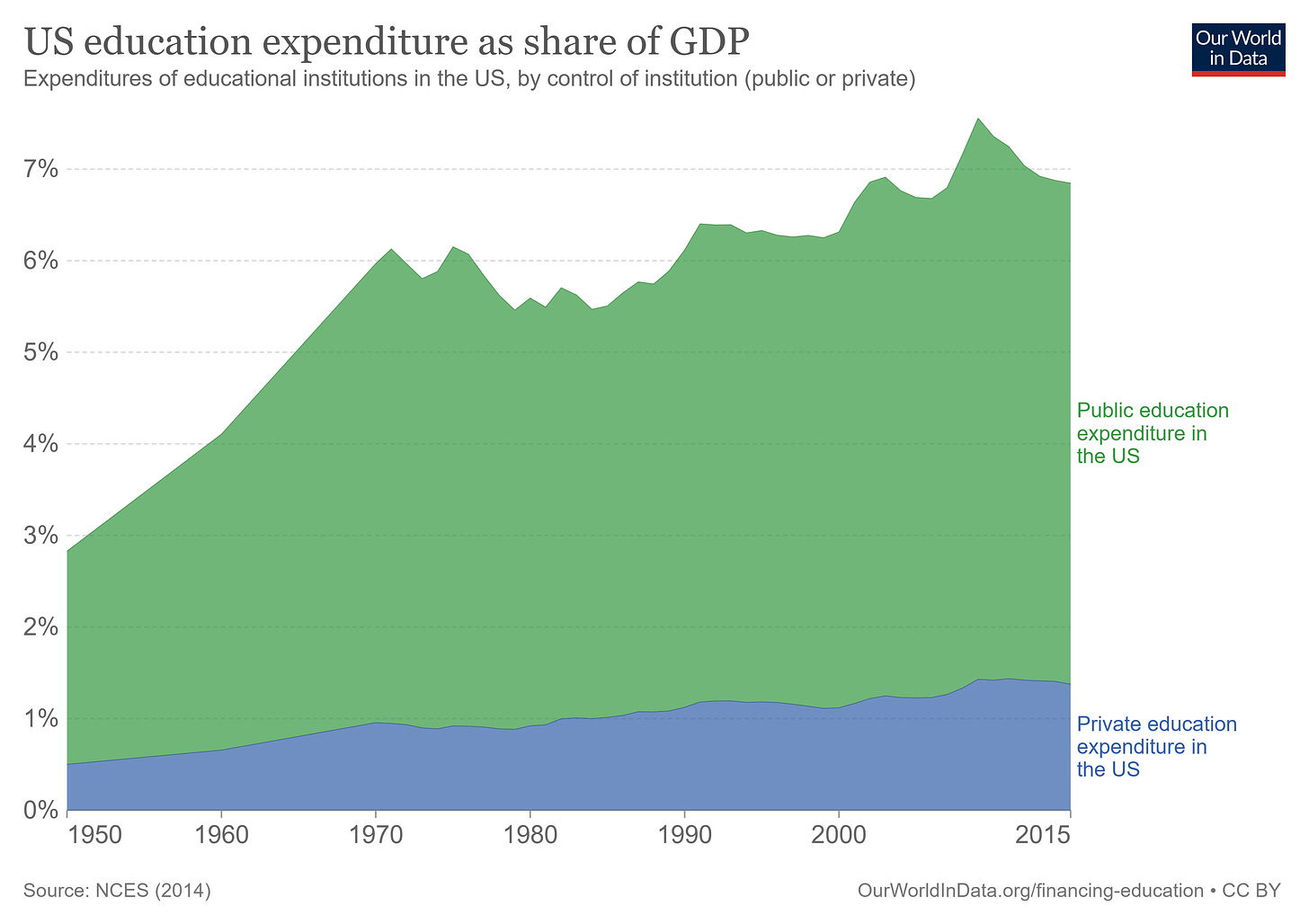

As usual, further study is needed. I don’t think the current scholarship is sufficient to outweigh the consistent observation, across many contexts and framed in many different ways, that those that spend more don’t consistently get better quantitative educational metrics in return. I do think that it’s an intriguing line of research. In the short term, though, I can’t see how it impacts the basic political calculus. If I want to spend more on schools, how do I take the current research to the public and ask them to accept tax increases? The political ask remains as hard to make as ever, by my lights. In 1950 we spent less than 3% of GDP on education in this country. Now it’s more like 7%. It’s hard to say that we have better educational or economic outcomes commensurate with that growing price tag. I am a free-spending, let’s-use-the-printing-press kind of a guy. But even I have to ask, how much are we ultimately going to have to spend, and at what point does just cutting people checks become a more efficient option?

It is worth saying that the view of a struggling American public school student as an urban Black child is not really justified. Because of America’s white majority, a very large portion of struggling students are white, even though their proportion is smaller than in the country writ large. Until recently a plurality of struggling students were white, although both changing demographics and the declining percentage of white students attending public schools have changed that, I believe.

I am curious how much the "what" could be the culprit here: anecdotally, my mother (who teaches in a wealthy district) and my roommates (who teach in a very poor district) spend approximately the same amount of money on school supplies each year, but what they buy varies a lot. My mom buys "fun" items: stickers, fidgets, different kinds of furniture so kids have options as to how they want to sit/stand, games, science experiment kits, etc. My roommates buy basic supplies their kids can't afford: pencils, notebooks, folders, etc. In poorer districts, is a lot of money being spent just to get kids to the same place their richer peers are? Does stuff like free lunches/breakfasts get accounted for? I'd imagine those are expensive programs. Throw in school districts chasing fads like iPads or anti-racism (my roommate's poor district spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on DEI training), and you can easily get lots of variation in what is spent. Doesn't help you figure out what specifically is useful to spend on, as you noted, but it does seem to me like the most interesting variable.

I'm curious if the research has delved into potentially "invisible" money like how much parents and teachers spend out of pocket? If District A is spending $500,000 a year on tutoring and the _parents_ of District B are spending $500,000 on tutoring, District A might look like it's spending a lot more even though the spending per community is similar.

From first quick glance at the two papers that try to use causal inference methods, they look pretty good. So spending probably does help. That still leaves the question of what are the main headwinds.

I suspect that the big spending increase in the 1950-1970 period was mainly just due to the big reduction in female oppression. Educated women had been pretty much forced into teaching or nursing with few alternatives. That kept wages artificially low. Now they can be doctors or lawyers etc. Perhaps it's an ironical reminder of how much more we reward lawyers, MBA-managers, financial advisers, etc. than we do people performing essential functions like teaching.

There's still a question of why subsequent increases didn't show up in improved outcomes, and that's where the headwind issue comes up.