What Would Success Look Like in American Education?

it's more complicated than you think

Last week, Matt Yglesias responded to a reader question about how well the American education system is performing. His response amounted to saying that we’re doing OK but not great, which is correct. One of the bigger sins of the education reform movement is that, in their zeal to prompt change at all costs, they’ve dramatically overinflated the problems with American schools in their rhetoric. Specifically, they tend to suggest a breadth of problems that we simply have never had; our struggles are with depth, deep academic problems restricted to a small portion of the overall system, found in particular geographic and socioeconomic enclaves. Saying “American education is failing” was always hyperbolic and inaccurate.

The problem with American students is not a problem with the median student, who could certainly do better but does pretty good. (They do very badly relative to the amount that we pay, but since past a certain point there is no relationship between school expenditures and student performance, it’s not like we should expect more for our money.) Nor would it be remotely true to suggest that students in the top percentiles in our system struggle relative to the world at large. Our top 1% or 3% or 5% are competitive with any country you’d care to name; our graduates crowd the greatest universities in the world, we produce a highly disproportionate number of the world’s knowledge workers, and American teams routinely win international academic competitions, despite what Reddit seems to believe. No, our education problems are where everybody knows they are: in a relatively small number of places that also struggle with poverty and crime, predominately in inner cities but also in decaying former industrial communities and in deep rural spaces such as in West Virginia and the Ozarks. I know this sounds simplistic or tautological - students who do great do great and who do badly do badly - but the point is that relative to peers, there’s no American education crisis until you get to the bottom half of the distribution.

Of course, this gloss on relative strength and weakness (good at the top, middling at the middle, bad at the bottom, relative to students at the same strata from other countries) assumes that good test scores = success. I think that’s not a very comprehensive or coherent way to think about education, and I say that as someone who understands that modern educational testing is remarkably effective. Testing gives us information about how students perform relative to some benchmark and to each other, but can’t in and of itself define how well our education system functions in broader, societal terms. Unfortunately, you can’t determine success or failure until you define what exactly success would look like, and I don’t think we’ve done that as a society. At all, really. What I constantly want to get people to do, in this conversation, is to think really, really specifically about what it is they’re trying to accomplish. When you say you want American education to get better, what does that mean? Everybody acts like the answer is obvious. I don’t think it’s obvious at all.

The simplest response to that question is to say that, of course, students should get smarter, and what that means materially is that quantitative indicators of academic performance should go up. Grades should go up. Test scores should go up. Graduation rates should go up. We want our kids to be doing better in school! Simple! Well, OK - whose numbers should go up? Which kids? And they say, all the kids! Which again seems simple enough and probably represents the most intuitive definition of progress in education. But in fact, we’re already in a big conceptual pickle here. You see, if every student improves, there will be no relative (and thus social/economic) improvement for those on the bottom. There’s all sort of benefits that we can identify that might come from everyone getting more educated. I tend to think that the country-wide economic benefits of more education are overwhelmingly concentrated in the performance of the top quartile of performers, but certainly there would be some positive effect on the economy and society if everyone did better in school. But if improvements for students at the bottom are matched by improvements for students at the top, the relative benefit for the individual improving student will be minimal. This is not particularly complicated, but people seem to struggle to understand it.

If you ask why education is important, the average person will certainly talk about personal enrichment and education as its own reward, and I will gladly talk about those values too. But most of the rhetoric about our supposedly failing schools is rightly concerned with the material, economic consequences of education - those who do well in K-12 go on to enviable colleges and from there to steady and well-paying jobs, which provide the basis for a safe and happy capitalist existence. School matters because kids who do well in school do well in life. We have so much angst about education because there’s so much riding on who does well in school, and a lot of kids don’t do well, with clear and disturbing racial dynamics at play. So we want to make everyone smarter and thus more likely to live a good life with material security and comfort. Again, OK.

But let’s take a moment here. As I will go to my grave saying, what’s rewarded in our society is not so much the absolute learning of new skills, knowledge, and competencies, but your relative ability in those domains. People think the world works like this: you go and get trained as an electrical engineer, someone needs electrical engineer skills, they offer you a job. But how it actually works is that people want to hire electrical engineers of a certain level of competency relative to other electrical engineers by choosing between them in a competitive process, and then pay them as little as they can while still enjoying the required skills and abilities. If you aren’t good enough relative to peers, based on the criteria of the company that’s hiring, they won’t hire you; if they aren’t offering enough money to fit your level of skill, you’ll let them hire someone less qualified than you. Your bargaining position is based on your relative attractiveness as a candidate compared to peers. The top 10% of the world’s electrical engineers are compensated extremely well. If that top 10% were taken by the Rapture tomorrow, the next 10% would get the compensation that went to the now-disappeared 10%. Because we’re rewarded for our relative ability. And if all American K-12 students got equally better, the students at the bottom would stay at the bottom in the labor market. Every student getting better leaves the distribution of performance entirely unchanged.

People act like the dynamic I’m describing is some irrelevant thought experiment, but that’s what’s actually happening, all the time! Consider the Black-white educational achievement gap that’s been the great education policy obsession for more than 40 years. On consistent metrics, Black students of today handily outperform Black students of the same age from 20 or 30 years ago. Black students of successive generations have improved relative to those of the past. The trouble is that students of other races have been improving too, and so absolute improvements among Black students over time have not resulted in the kind of relative gains that would close the racial achievement gap.

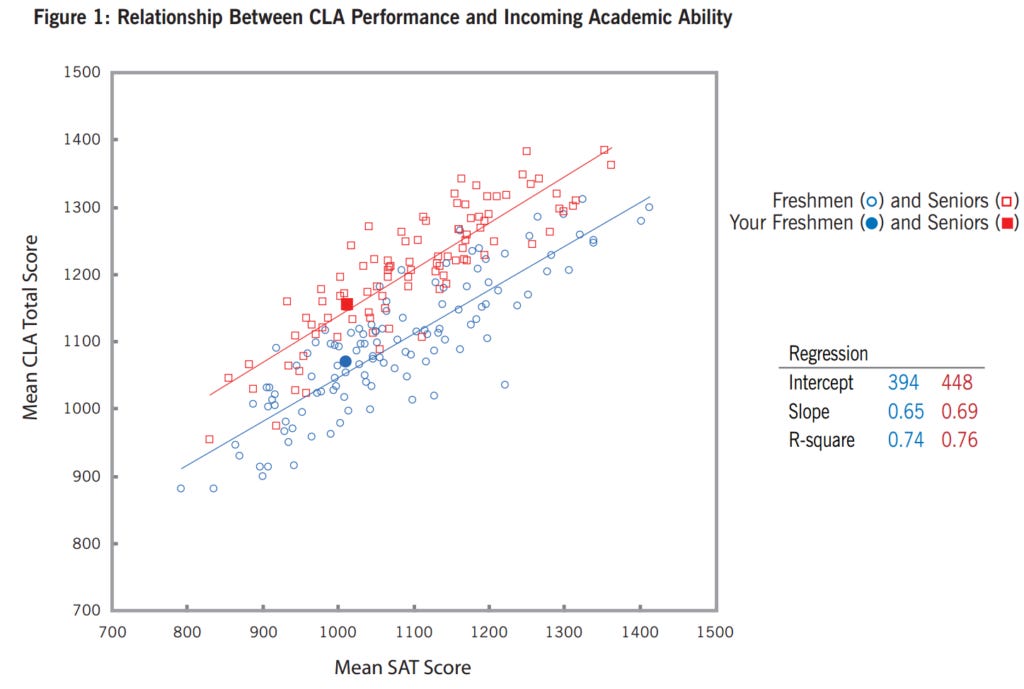

I’ve shared this image a half-dozen times before, not because the actual data is important but because it’s such an elegant visualization of this immensely-consequential dynamic. The blue scatterplot represents mean institutional SAT scores correlated with mean freshman performance on a test of college learning, the red line the same but with senior performance. As you can see, there’s robust growth from freshman to senior year in this dataset. But the problem is also plain to see: even after performance gains at those colleges whose students entered with low SAT scores, their students are still underperforming where high-SAT students started college, and since the high-achieving students made gains too, there is no system-wide gap closing between the schools with the lowest and highest pre-entry ability. This Zeno’s dichotomy paradox of education is a generalizable condition throughout our system, it has massive consequences, and I find that it’s barely discussed.

There’s also the preliminary question of whether we actually can get everybody to improve in the way I’m discussing. I’m guessing people would assume that I would be fatalistic about that question, but that’s not the case. Indeed, that’s what we’ve been doing for ~150 years, seeing people get smarter all the time. It just doesn’t happen particularly quickly, and (to repeat myself) we have no reason to believe that this kind of slow improvement in educational outcomes over time could reduce the relative gaps that produce bad social outcomes. Since everybody’s getting better, relative gaps don’t close. We would want that, though, right? To close relative gaps? In many instances, yes. In the broadest terms, no, which leads to the next point.

Some people say what we want is educational equality. Equality, that’s the ticket, that’s what we want. (This is genuinely something people tell me, that the goal is some such state called educational equality.) I don’t think it should be hard to poke holes in this. Among other things, actual educational equality, where every student performs exactly the same, ensures that there is no excellence. Again, this is not a meaningless thought exercise. You can see this exact tension at play in recent (deeply misguided) efforts to prevent students from taking algebra in middle school, based on the reasoning that some students taking algebra while others don’t increases racial inequality. That kind of heavy-handed effort can’t actually create equality, in the real world, and if it could it would be an equality achieved entirely by restricting the flourishing of students at the top. This is the easiest way to close the racial achievement gap, criminalizing sending white and Asian kids to school, but it’s all pulling down, no pulling up. All else aside, the achievement of educational equality would always result in erosion of excellence in one way or another. Perhaps if everyone was equal at the highest rung of achievement - whatever that could mean absent relative benchmarks - we could call that excellence. But, of course, we can’t achieve that kind of equality, at the top level of performance or any other. Because not all students are created equal.

Aha! They say. Not all individual students created equal, but all races/genders/ethnicities/socioeconomic classes/etc. created equal in the classroom! This is the perspective that says that the goal is to ensure proportional representation across different demographic groups, so that both male and female students make up half of the top 10 in a given high school class, so that the 13ish% of K-12 students who are Black end up being 13ish% of college graduates, so that poor kids are found in elite academic spaces in proportion with their overall numbers. And of course I would like to be able to snap my fingers and bring such a world into existence by magic. But proportional representation leads to the dilemma that (you knew this was coming) inspired my first book. The trouble with proportional representation is that, while it helps ameliorate certain obvious social injustices, it still leaves 20% of the population in the bottom quintile of every performance distribution. That bottom 20% may now represent a perfectly diverse rainbow, but the people stuck in it are still fucked. One of the early title ideas I thought of for the book was After the Achievement Gap, which honestly maybe I should have gone with. The point is simple: closing the racial achievement gap has been such an all-consuming policy fixation for so long that the basic question “What can and should we do for the students who are simply untalented?” has gone ignored. You could tell a student who finds themselves in the bottom decile, “Good news, the system is proportional now!” But they’re still going to struggle for the rest of their lives.

(The critics who complained that the book must have endorsed pseudoscientific racism when it didn’t, and the “human biodiversity” people who made fun of me for not endorsing pseudoscientific racism, both tried to force me into exactly the straightjacket I was refusing to wear: considering education only in terms of group inequalities rather than in differences between individuals, the consequences of those differences, and what we as a society owe to those on the bottom of the performance spectrum who suffer because of it.)

Finally, you have what may be the most superficially attractive goal of all, equality of educational opportunity. In this formulation, we don’t concern ourselves with who succeeds or fails, only with whether everyone has an equal shot at success in the classroom. Well, I’ve been documenting problems with the concept of equality of opportunity in society writ large my whole career, and if anything those problems are even more acute when we look at education specifically.

Equality of opportunity is often suggested as a more achievable, realistic alternative to equality of outcome, but in fact since any difference at all can be represented as an inequality, and because there is no limit to the number of influences and factors which could prevent true equality of educational opportunity, the demand is revealed to be quite extravagant.

Knowing when we’ve achieved equality of opportunity is close to impossible. I can tell you if everybody falls within X income range, has Y wealth, enjoys Z material condition. I have no idea how to tell if equality of opportunity has been achieved, because (again) the number of influences that contribute to equality of opportunity are endless. And to the people who struggle, minor influences are going to frequently appear very consequential indeed.

Once we acknowledge that literally any difference in condition amounts to an inequality in opportunity, we must recognize that equality of opportunity and equality of outcome are one and the same - the only way you’d ever achieve equality of opportunity is if you had created identical lived circumstances, which is another way to say… equality of outcome.

If we acknowledge that there is any inherent element to academic talent at all, whether from genetic influence of any other, we are confronted with the question of including that inherent influence within the definition of equality of outcome (in which case we can’t achieve it) or excluding it (in which case we’re blaming individual people for their lack of inherent talent, which they can’t control, which doesn’t seem very equal at all.)

I could go on. In general the concept of equality of opportunity either requires a belief that human beings have no inherent strengths and weaknesses, which no one believes, or it requires comfort with people suffering because of those strengths and weaknesses when they can’t control them, which seems to undermine the very purpose of equal opportunity and which most people in contemporary times won’t get on board with. It’s not an easy nut to crack.

Of course, there are practical syntheses of these possibilities, and I suspect that most people are comfortable muddling along in that way. Certainly you can say that you want the bottom to get closer to the median (accepting that this will move the median…) while hoping that racial inequalities are eased as racial averages grow closer, all against a backdrop of system-wide improvements relative to criterion references and benchmarks. To which we would have to say “and a pony!,” but it’s not an unattractive kludge. People will go to considerable lengths to try and reconcile various tensions in their education thinking, on the fly. I get a lot of this; when I point out that improving things for students at the bottom requires that they perform better relative to peers above them, and also that smart kids keep learning which makes that harder, I get notions like “well, if the curve just had a heavy left skews….” I think that you can get into philosophical questions about what it means for the median to move in that way, but let’s not. Muddling through with a general goal of improving outcomes for everyone while maintaining a special focus on shrinking racial gaps is pragmatically sufficient; you could do worse. But since the education reform crowd has embraced absurdly outsized goals and soaring rhetoric for decades, they’ve bitten off more than they can chew conceptually, and they haven’t really grappled with the consequences.

I think it’s very valuable to press people for what they think represents success in education, in mundane terms. Because it’s not as intuitive as they think.

I think this mostly traces back to the liberal bromide that we'll somehow solve inequality via education without actually changing the underlying socioeconomic structure of society, which is absurd on the face of it. If you handed every student in America a PhD in a STEM field, there'd be nowhere for most of them to go. There are only so many of those positions to go around, and no amount of schooling will change that. It's all pure neoliberal ideology, maybe with a human face, but neoliberal ideology just the same.

The better solution would be to change society so you could live a perfectly comfortable life just doing lower level jobs. I got a literature degree the first time around in college, and I never tire of pointing out that if college was less expensive and wages were higher it would be totally fine to just learn about things you liked and enjoyed. What a wonderful world that would be. Instead, with tuition and employment prospects being what they are, every single aspect of the education system is tailored towards making sure you have the best chances to get one of the dwindling number of high income positions available. Everyone loves talking about education reform, but you can't consider education on its own. It is absolutely a product of society on the whole and has all the same problems. Gyorgy Luckas had that whole thing about how the most defining aspect of the Marxist perspective was looking at society as a totality, on the whole. How all the different parts functioned as part of a larger system, and that's applicable here.

Freddie writes: "The top 10% of the world’s electrical engineers are compensated extremely well. If that top 10% were taken by the Rapture tomorrow, the next 10% would get the compensation that went to the now-disappeared 10%."

This is something of a pointless quibble, and I'm sure Freddie knows it, but because technically correct is the best kind of correct, I think that statement is partially true and partially not.

The best 10% of the world's electrical engineers are more productive than the next 10% - on average, they solve problems better and faster, their documentation is better, and they otherwise are better at things we want electrical engineers to do. So if we Raptured them, and replaced them with new, less good engineers, the new top 10% wouldn't be as productive, and wouldn't get paid as much for two reasons. (1) Generally, a firm's maximum payment to an employee is going to be capped at the employee's expected productivity - if you're paying an employee more than they produce, you're usually better off letting them go and hiring someone you can pay less. (2) Because there's less total stuff in the world now that the former top 10% has been replaced by a bunch of new engineers from school, there is less to pay everyone, including the new top 10%.

Freddie's essential point that making everyone smarter wouldn't reduce income equality in a capitalist system is completely right. But it would make all of us better off materially, by increasing the amount and quality of goods and services and the amount of leisure we consume. But again, that doesn't take anything away from Freddie's point. :)