Elite Education Journalism: Still Ideology at Its Purest

you don't get to write about education in fancy places unless you TOE the line

Years ago, in the before times, I wrote this post about a New York Times piece on New York’s forays into “school choice.” As I said then, the NYT story was only remarkable in how unremarkable it was - it was a very ordinary expression of how elite opinion on education functions. Which means that it reflected deeply incoherent attitudes towards what we want from education as well as what can be accomplished and what are the best means to do so. Now the Times is back with another bit of elite consensus-making that’s starved for logic. You can see this at work in its basic reason for being: it’s a piece about how an absolutely massive influx of cash into schools led to profoundly modest increases in student performance against benchmarks but nevertheless huffily insists that school funding influences performance. This is business as usual. People in elite policy and media circles say that more school funding will “fix” our schools, and there are no facts that are going to push them off of that position.

For the tedious bit about my qualifications, check this footnote1. I am uninterested in whether they’re good enough; we tend to embrace a consequentialist perspective on who is and isn’t qualified. That is, only those who tow the official line on education, in big-think terms, are recognized as possessing the necessary qualifications. They’re not letting anybody that doesn’t accept the Official Dogma of Education into the conversation. (I was able to sneak a piece in at WaPo by pretending it was about Donald Trump.)

Anyway, the NYT article reflects on two studies conducted in response to a truly massive injection of cash into our school system, thanks to Covid relief bills, and the attendant “modest” improvements to quantitative indicators. This advantage is summarized as “For every $1,000 in federal aid spent, districts saw a small improvement in math and reading scores.” You can dig into the studies, although I wouldn’t put too much stock in either direction; ed data is noisy and the pandemic presented so many confounds I wouldn’t know what to do with them all. I’m more interested in this defensive attitude towards the whole project:

A large body of research shows that increased spending on education is associated with improved student outcomes, especially for students from low-income families.

If you’re unaware, this is taking one of the most deeply-contested “facts” about education that we have and representing it as settled. As I discuss at length here, it is not. There are longstanding arguments that additional funding does not in fact improve quantitative student learning outcomes, at least past a certain bare-minimum that developed countries already easily clear. Why do those arguments persist in the face of forceful and sustained elite opinion that insists that our education problems are funding problems? Probably because our education problems are demonstrably not funding problems.

What you get a lot of, these days, is education researchers assembling very complex (and thus opaque) models that seem designed specifically to arrive at the conclusion that school funding can fix education, whatever that means. On the other side, you have, well, reality. Reality is not kind to this idea. We live in a reality where New York annually spends the most on school funding per pupil while barely outperforming Utah, which spends the least; where the United States, a very rich country, spends around eight times as much per pupil as Vietnam, a very poor country, and yet is essentially at parity in international educational comparisons; where the United Kingdom spends dramatically more on education than South Korea but does dramatically worse. We’ve been regressing expenditures on outcomes for a long time and getting the same result - money doesn’t determine student performance. And, really… why would it?

The dynamic is found at every level you choose to look at. Detroit significantly outspends Ann Arbor in per-pupil funding. 56% of students in Ann Arbor public schools met state standards in math proficiency in 2023; in Detroit public schools, that figure was 9%. If you think racial demographics are too big of a confound for that to be a good comparison, consider West Virginia’s McDowell County School District (88% white, $13,070 per student per year, 18% proficient in math) and Jefferson County School District (75% white, $12,438 per student per year, 32% proficient in math). Washington DC spends extravagantly on schools in both a national and international context; their quantitative outcomes are consistently awful. There is no credible argument that student performance is a function of how much their school, district, state, or country spends on schooling, none. And the argument that such spending even meaningfully influences student performance is remarkably thin on the ground. After all, if they had a big influence, well, they’d be having a big influence.

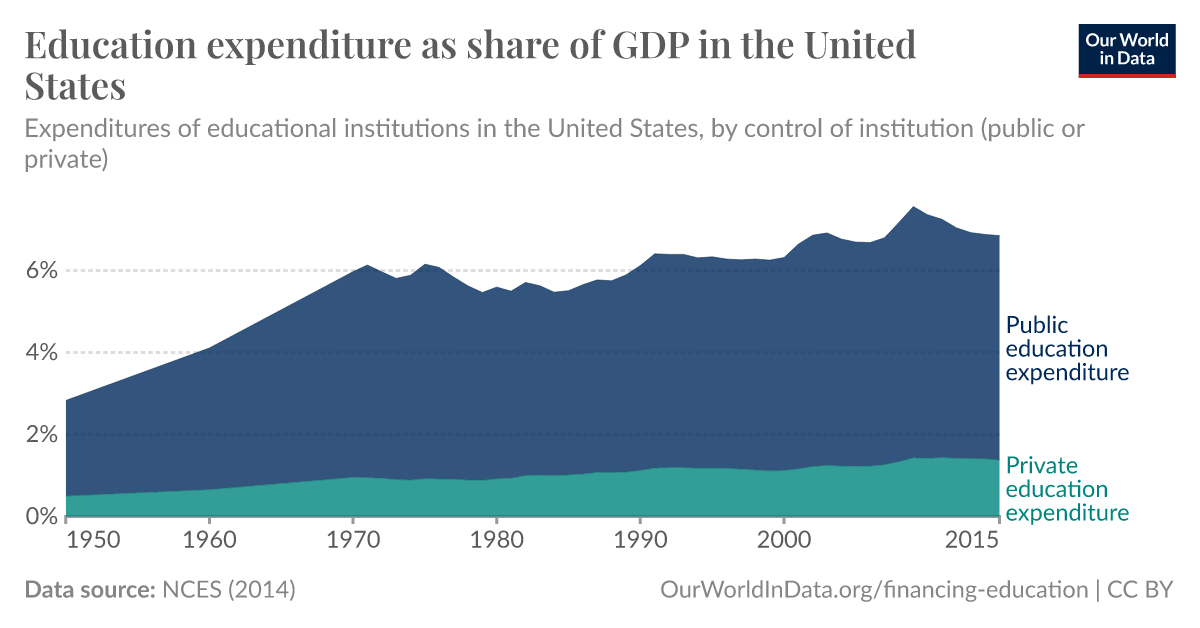

This is all bound up in conventional wisdom that was developed decades ago and is now well out of date. For example, that we’ve somehow “defunded” K-12 education. Just flatly wrong, and yet I hear it all the time.

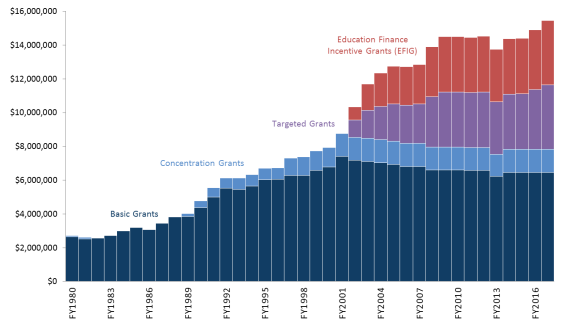

On the scale of a decade and expressed in dollars, or on the scale of three-quarters of a century and expressed as a percentage of GDP, we’ve spent more and more and more on education. No miracles in academic performance. You want funds earmarked for poor kids specifically? Here you go, here’s Title I spending:

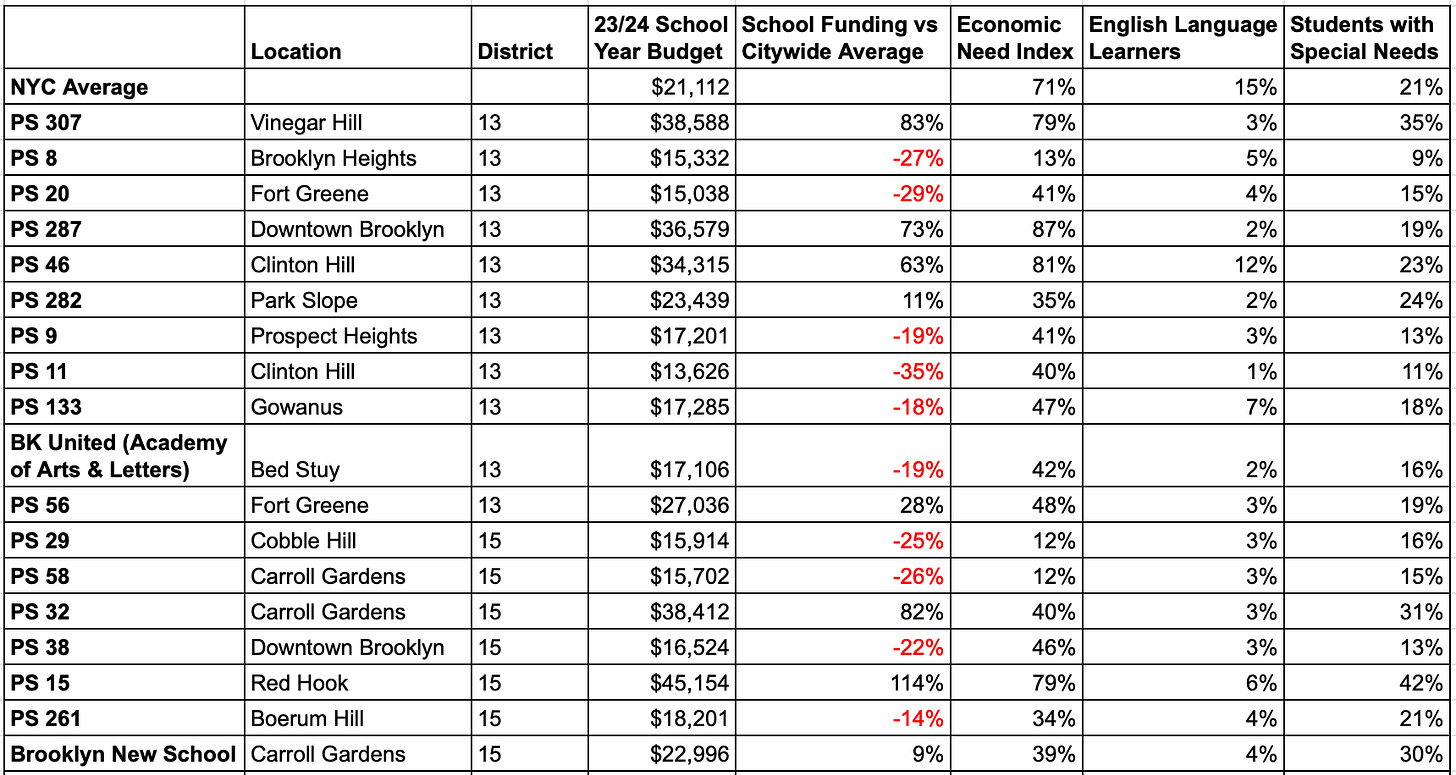

But the money gets concentrated in the wealthiest schools, right? No, it does not. The opposite is true. Poorer and Blacker schools get more public funding than richer and whiter, for the obvious reason that we’ve been throwing money at the achievement gap for ages. This is a consistent finding and can’t be ignored. For the micro, let’s take a look at some schools in Brooklyn, a borough in the highest-spending state and the site of a great deal of racial and economic diversity.

Do you see how schools with wealthier students (that is, from low Need Index neighborhoods) tend to spend less compared to the citywide average? For example, PS 8 in Brooklyn Heights, PS 58 in Carroll Gardens, and PS 29 in Cobble Hill have the three lowest per-pupil expenditures and also three three lowest Economic Need Indexes. Or just look at the stark difference in both figures for the two Carroll Gardens schools. I think most people find this to intuitively make sense, to spend the most on students who face the greatest economic hardship. And this makes sense to me, too, even though I don’t think that funding influences quantitative outcomes, as I want schools to be safe and comfortable places which present students with opportunities for enrichment. But note that this directly contradicts the absolutely unshakable liberal assumption that poorer and higher-minority schools and districts receive less funding. What do you think all of these decades of do-gooders have been up to? Since at least the Reagan administration we’ve taken a “money first” approach to achievement gaps.

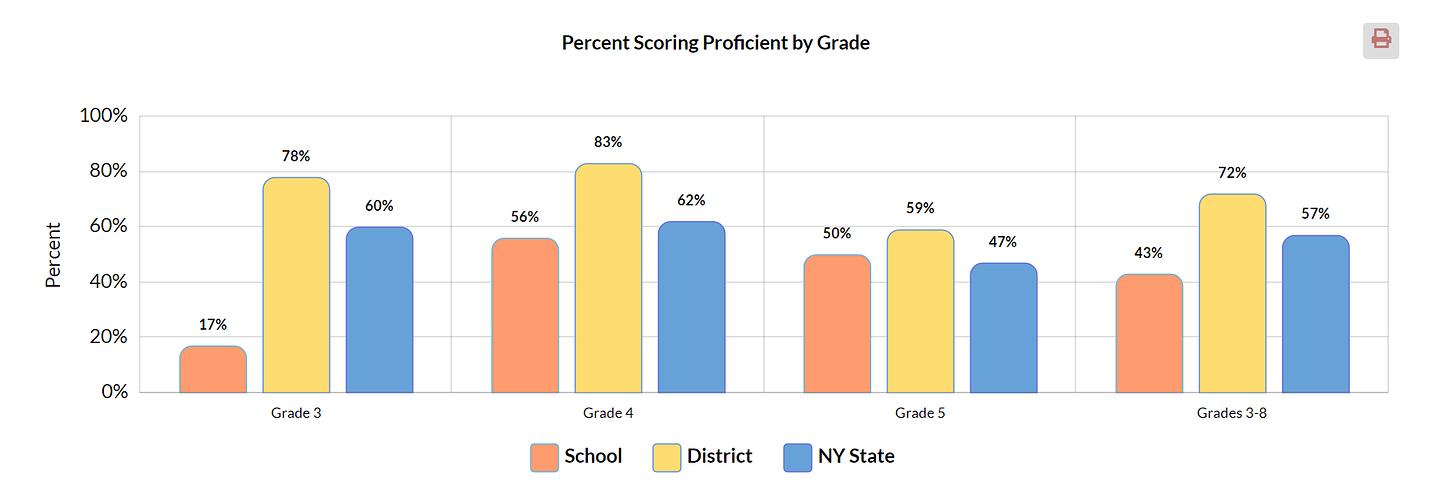

The NYT piece quotes experts who are ensconced in the Official Dogma and who would never let these studies shake them out of it. They engage in the usual mystification of saying “you need to spend the money well.” This of course makes the truth claim non-falsifiable: if money doesn’t improve student performance, you can just say that it wasn’t spent effectively, with no responsibility to ever ask if maybe it’s time to accept reality. (Am I supposed to believe that Vietnam has some brilliant strategy for spending educational dollars that we simply can’t replicate?) I mean, look at that chart. $38,588 per student at PS 307 in Vinegar Hill. That’s almost exactly the median income in Brooklyn! Don’t you have to start wondering, at some point, whether that money would be better spent on food or clothes and medicine for the students? And how much higher can you force that number before people start asking for results? Because here’s what taxpayers are getting for their money:

30% lower than district average proficiency. For 83% higher funding than the city average. Someday people just aren’t gonna roll with this anymore.

The outdated or just incorrect truisms will never die, or so it seems. Class size is the key! No, even proponents of smaller classes usually acknowledge that the effects are small and inconsistent. We’re understaffed! No, public school staffing levels per 1,000 students have increased dramatically. The problem is that schools are funded locally, which leads to inequality! No, that’s out of date. State funding is now at parity or higher than local funding in public schooling, and federal funding has increased for decades. Try again. And all of this happened before the Covid-relief spending explosion. I am just at a loss as to how people continue to promulgate these blatantly false narratives. Yes, more school funding is good when it gives students safer, more comfortable spaces in which to learn and to be nurtured as human beings. It’s good when it’s intended to provide enrichment in a holistic sense, with trips to the zoo and picture books and ant farms. Trying to use school funding to juice grades, test scores, or graduation rates is an experiment that has been failing for longer than I’ve been alive. Asked and answered, guys. Asked and answered.

I don’t use this term often, but this sure feels like what people mean when they use the term gaslighting. You have a country that spends profligately on education but which dramatically underperforms many others that spend much less, you have the same dynamics in states and districts, and you have an elite consensus whereby New York Times reporter Sarah Mervosh doesn’t just suggest that the consensus is correct, she insists on it as an assumption that will not be challenged in her piece. The best we get is vague stabs at the cost-benefit analysis, which is then not actually performed. I’m surprised she didn’t trot out Eric Hanushek so he can continue his years-long publicity apology tour.

How wide does the gulf have to be between spending and outcomes before people stop putting stock in a handful of models built on tendentious premises, developed by researchers who are clearly determined to engineer a particular outcome? Brow furrowing over this disconnect is constant; New York, by itself, has its own mini-genre of such pieces. But they’re all useless if they don’t include the most relevant information:

Regardless of whether we spend enough in some Platonic sense, by any historical or international comparison we spend extravagantly on public education in this country

We have vast amounts of data, compiled at every level of organization, that show that better-funded schools are not in any consistent way whatsoever producing higher-performing students, often the opposite, while the models suggesting otherwise have no similar backing in easily-observed relationships

Student-side factors like parents’ level of educational achievement are vastly better predictors of student outcomes than school-side factors like funding, and in general, schools control very little of the variation in student outcomes

Poorer schools with more students of color on average receive more per-pupil funding that schools with richer and whiter students

That finding, though often treated as scandalous, should be utterly unsurprising given that we have shoveled money at the racial achievement gap for 40+ years.

There’s a lot of influences at play in the elite consensus; nonprofits don’t get funded by telling donors what can’t be accomplished, for one thing. Pundit’s Fallacy logic and the tendency to look where the light is also explains some of it. “We can’t fix poverty and we can’t fix parents, so the answer has to be found in the schools.” It’s the same old magical thinking.

Our problem is a) we’ve got social problems related to race and class that cannot be resolved in the classroom and b) students possess a level of intrinsic academic potential which is likely heavily influenced by genetics and definitely influenced by environmental factors that parents have limited ability to control and which public school educators can’t possibly influence. But the concept of an individual student’s intrinsic academic potential is not discussed in polite company, even as everyone knows it exists. (I assure you that parents do not sincerely believe that their kids have the exact same potential as everybody else’s kids.) Meanwhile, conceptual confusion abounds. The NYT piece is framed around closing Covid learning loss gaps. But if you closed all those gaps and restored the performance distribution of 2019 you’d still have a bottom half, bottom quintile, bottom 10% of students. What does success look like for them? I don’t know. The elite consensus doesn’t know either.

What would I do if I was king? Gather population-level data using stratified samples, so that we never have kids or teachers laboring under tons of testing. Stop trying to move students around dramatically in the performance spectrum because we have no reason to believe we can achieve such a thing. Reorient schooling towards making childhood safe, nurturing, and stimulating for all, giving everyone a chance to learn what they like and what they’re good at so they know what to pursue professionally. Of course, some will fail in their professions regardless, which is why the real goal is to build a humane and just society. If you really care about kids who struggle at school, you’ll stop trying to shove their square pegs into round holes and instead invest in a robust public sector that will protect them from poverty and need, no matter how they perform in school. You can read all about it.

I hold a BA in English and philosophy from Central Connecticut State, an MA in Writing & Rhetoric from the University of Rhode Island, and a PhD in English from Purdue University, where I focused on assessment of student learning, particularly on writing assessment and education policy related to assessment. My dissertation was about the CLA+, a test that measures college learning, and the social and economic conditions that were (at the time) putting pressure on colleges to assess. I have also served as a peer reviewer for the academic journal Language Testing. In 2016, the New America Foundation contracted me to write a policy paper on the then-burgeoning field of standardized assessments of college learning. I have presented on assessment issues at several major conferences, and in 2023 I delivered the keynote address at the National Test Prep Association conference.

At Purdue I worked in the Oral English Proficiency Program, participating in developing and rating for the Oral English Proficiency Test, a proprietary assessment of spoken English for speakers of other languages. In the last year of my PhD studies I served as the assessment coordinator of the Introductory Composition at Purdue program, where I developed and implemented an essay-rating assessment system, including creating prompts and rubrics, training raters, and collecting and analyzing data. Relevant coursework from grad school includes classes in frequentist statistics and multivariate analysis, experimental design, quantitative research design for language testing, qualitative research design for education research, empirical methods for composition research, writing assessment, curriculum design for second language pedagogy, and an independent study in empirical research in writing pedagogy.

For four years I served as the Assessment Manager at Brooklyn College in the City University of New York, where I was in charge of assessing student learning, helping faculty to develop assessment systems for their departments and collecting and presenting college-level performance data. In that capacity I developed dozens of in-house assessment systems, collected, analyzed, and presented data on student performance. I have taught more than a dozen sections of freshman composition, classes in oral English skills for graduate students, a course for advanced undergraduates in public writing, and dissertation workshops for doctoral students. I worked for 18 months in a public school district, primarily as a paraprofessional in a program for students with severe emotional disturbance and as a long-term sub in middle school social studies. I also did test prep of various kinds for four years. I have done contracted work for testing-adjacent companies and consulting for the head of a nonprofit dedicated to solving social problems. I am approached to speak at conferences and to provide insight on education-related issues regularly. My academic CV is available here.

![U.S. Public Education Spending Statistics [2023]: per Pupil + Total U.S. Public Education Spending Statistics [2023]: per Pupil + Total](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7f724b6c-b277-4e48-8a5d-78790a1f465a_800x526.png)

The fact that most of the new funding in education goes to a bloated administrative class rather than teachers and instructors make me wonder if perhaps that are ulterior motives to the never ending calls for additional funding.

I think you mean “toe the line.”