Education Doesn't Work

student ability is remarkably static and predictable from pre-K to college and beyond, and this means that our social contract is broken

Note: this post has been superceded by a new and improved version. Please see that version for my definitive take.

This post well exceeds Gmail’s size limit, so please click the “view entire message” link if you’re in Gmail or go here and find the post. I’ll give you a couple days to let this one marinate. I will be participating in a virtual sociogenomics forum hosted by the University of Bristol on April 26th and will share the video when I have a link.

Stuck in Place

There’s this guy Jay Joseph. He doesn’t like me, but to my annoyance I like him. He’s been waging a one-man war against the field of behavioral genetics/population genomics for decades, arguing that we can’t responsibly say that genetics influence behavioral traits like academic performance. He has a blog and writes frequently for Mad In America, a kind of catch-all website for heterodox thinking on topics in psychology that I previously identified as a hub for the anti-psychiatry movement. He’s kind of a grouch, which is an underrated quality in writers and thinkers, and that grouchiness has produced a persevering quality I respect. I suspect he’s wrong on the merits of whether genetics influence cognition and behavior, and like so many making these complaints he is clearly motivated by moral and political objections that he rationalizes as methodological criticisms. But I admire the tenacity with which he pursues his project, particularly given that (as far as I can tell) he holds no formal academic appointment.

I bring him up because I think I have made the mistake of burying the lede when it comes to my basic claim about education and why it cannot create socioeconomic equality (or even mobility, liberalism’s false god). If I had the chance to do my book over again, I would not remove the genetic argument, but I would de-emphasize it12. To be clear, I do think that our genes influence our cognition and thus our academic outcomes. We and our brains are the product of evolution and genetics is the instrument of evolution. In an intuitive sense it would be incredible if there was no influence from genetics on any organ, including the brain, or on that organ’s functioning. But people who are much smarter than me will have the final say.

The problem with including the topic in the discussion is that genetics and intelligence is an inflammatory subject, and it has obscured the point that I am much more interested in. This point is both totally banal and yet potentially revelatory given our educational policy conversations: mobility of individual students in quantitative academic metrics relative to their peers over time is far lower than popularly believed. Students sort themselves into an ability hierarchy at a very early age and tend to stay in their position in that hierarchy for the remainder of their lives, to a remarkable degree. The children identified as the smart kids early in elementary school will, with surprising regularity, maintain that position throughout schooling. Do some kids transcend (or fall from) their early positions? Sure. But the system as a whole is quite static. Most everybody stays in about the same place relative to peers over academic careers. The consequences of this are immense, as it is this relative position, not learning itself, which is rewarded with economic gain by our society.

This is what I think people like Jay Joseph need to grapple with: even if you effectively refute the genetic explanation for differences in educational outcomes, you cannot dismiss the summative reality of limited educational plasticity. What I am here to argue today is not about a genetic influence on academic outcomes. I am here to argue that regardless of the mechanism producing this effect, most students stay in the same relative academic performance band throughout life, defying all manner of life changes and schooling and policy interventions. People like Joseph need to provide an accounting of this fact, and they need to do so without falling into endorsing the naïve environmentalism that is demonstrably false. And people in education and politics, particularly the liberals who insist education will save us, need to start acknowledging this simple fact. Right now they’re wasting their time.

Relative vs Absolute

The title of this post is, I acknowledge, something of a troll. Kids learn at school all the time. You send your kid, he can’t sing the alphabet song, a few days later he’s driving you nuts with it. Sixteen year olds learn to drive. We handily acquire skills that didn’t even exist ten years ago. Concerns about the Black-white academic performance gap can sometimes obscure the fact that Black children today handily outperform Black children from decades past. Everyone has been getting smarter all the time for at least a hundred years or so. So what’s the issue?

The issue is that these are all markers of absolute learning. That is, people don’t know something, or don’t know how to do something, and then they take lessons, and then they know it or can do it. From algebra to gymnastics to motorcycle maintenance to guitar, you can grow in your cognitive and practical abilities. The rate that you grow will differ from others, and most people will admit that there are different natural limits on various learned abilities between individuals, but everybody can learn. People think they care about this absolute learning. But what they actually care about, in general, and what the system cares about, is relative learning - performance in a spectrum or hierarchy of ability that shows skills in comparison to those of other people.

If Harvard (or Caltech or whoever) selected an incoming freshman class, and then aliens came to earth and abducted every one of them, Harvard would just reach into their bag of valedictorians and admit the next rung of students on their list. Those students would presumably have meaningfully lower ability in absolute learning compared to their abducted peers, if Harvard’s selection process means anything3. But they’d be the best relative to who was left. Correspondingly, would that reduced level of absolute learning mean that they wouldn’t receive the advantage that a Harvard degree confers in the labor market? Of course not. They would still be perceived as the cream of the crop relative to labor market peers. You sell your academic credentials in a market; their value is a function of their supply and their demand. We know that the college wage premium is to a large degree a simple function of the ratio between the number of jobs that require a college degree and the number of applicants who have one. (Duh.) The absolute learning represented by that degree is not the relevant criterion. The position of the student in the hierarchy is.

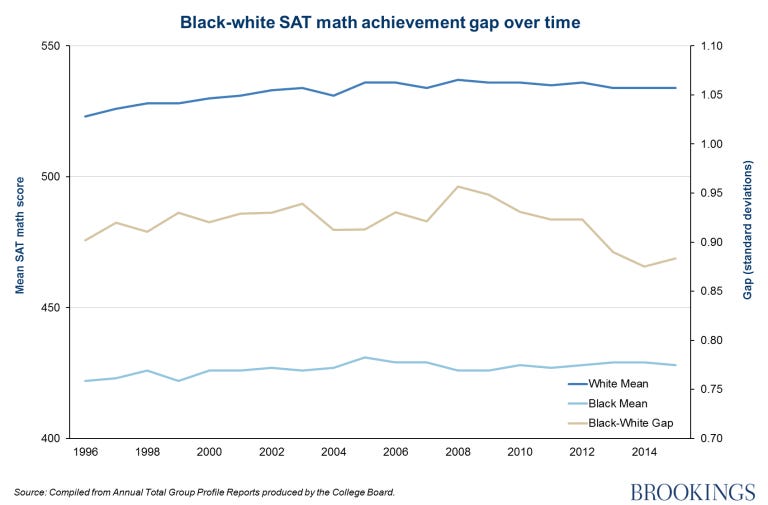

I mentioned above that Black students, even Black students from low socioeconomic status (SES), have been improving steadily in absolute terms over time. What a Black third grader (or any third grader) can do today is head and shoulders above what one could do 30 years ago. But we still obsess over the racial achievement gap. Why? Because it is relative performance that results in college acceptance and labor market improvements, not absolute, and white kids have been learning this whole time too, so Black student gains don’t advantage them4. When parents read their child’s state standardized test score results, are they doing so alongside a copy of the test or a detailed description of what the specific tested content was? No, because they don’t care. They care how their kid did compared to the other kids. When teenagers obsess over their SAT scores, they’re not motivated by their ability to answer reading comprehension questions correctly. They’re motivated by the fact that their SAT score percentile will have a meaningful impact on where they go to school, and (in their minds at least) how much they will eventually earn. This is the prioritization of the relative over the absolute, and it is a dynamic found all over education.

Of course, changes to relative learning for any individual or subgroup requires changes in absolute learning somewhere - you learn more than peers or less in an absolute sense and your relative position improves or declines. But in a fundamental sense it’s key to understand that, for example, the pharmacy school graduates who emerged into a world where they suddenly had vastly more labor market competition didn’t know less than those who had the good fortune to graduate a decade earlier. They probably knew more. But that absolute learning was not relevant from a career perspective; their relative position next to thousands of other new graduates was5.

Unfortunately, a large amount of education discourse in our media fails to understand this distinction. More unfortunately, while we can reliably prompt absolute learning gains in our students, we cannot reliably change their relative placement in the distribution, as I will demonstrate.

Is this about the racial achievement gap?

No. As I have argued repeatedly, including in my book, it is perfectly consistent (and in fact quite sensible) to believe that the observed academic differences between individuals are partly because of intrinsic differences (whether genetic or not) while the differences between certain groups (such as genders or races) are purely environmental. That is in fact what I believe - that within-group variation (differences between any individual kids, including within the same race) has an intrinsic component while the between-group variation between races is environmental. Racism is a powerful and multivariate force that could suppress the performance of Black students even while those students have varying individual academic potential like anyone else. To spare people who have heard this song and dance from me before, I will explain more in a footnote6. For an endorsement of this position from someone who (unlike me) has scholarly credentials in this area, you might consider Richard Nisbett’s Intelligence and How to Get It, although I do not share Nisbett’s optimism about the capacity to improve academic outcomes generally.

The Evidence

To begin with, while my great preference would be to use the term “educational mobility” to refer to the phenomenon I’m describing (the movement of any given student within an academic distribution or hierarchy, or the total movement within that distribution or hierarchy over time), that term already belongs to the relationship between a child’s educational outcomes and that of their parents, or intergenerational mobility. (Which is, as a generic statement, rather low.) This is especially annoying for me because I find liberal fixation on intergenerational educational mobility to be as misguided as their fixation on intergenerational economic mobility. Both are orthogonal to what we actually care about. Of course, there is a relationship: low intergenerational mobility suggests lower movement in the peer hierarchy as well as in comparison to parents; if students are moving around a lot relative to peers, they must be moving relative to static parent outcomes. Regardless, I’ll try to avoid using the term “educational mobility” in this essay to avoid confusion, unless I am specifically referring to intergenerational mobility.

We can express the staticity of relative educational outcomes quantitatively, in a variety of ways. The simplest is to observe that by far the most consistently effective predictor of future academic performance is prior performance. This paper summarizes the reality simply:

The present study shows that individual differences in educational achievement are highly stable across the years of compulsory schooling from primary through secondary school. Children who do well at the beginning of primary school also tend to do well at the end of compulsory education for much the same reasons.

Academic skills assessed the summer after kindergarten offer useful predictive information about academic outcomes throughout K-12 schooling and even into college. At essentially any point along a given student’s educational journey you can take their outcomes relative to peers and have strong predictive ability about their performance at later stages. (Past performance predicts future performance so well that it seems most education researchers don’t think of it as a predictor at all.) I could pull out reams of data demonstrating this. If you’d like to go short-term, student performance in third grade predicts student performance in fifth grade very well, as you would imagine. Long term, third grade reading group, a very coarsely gradated predictor, provides useful information about how well a student will be doing at the end of high school. The kids in the top reading group at age 8 are probably going to college. The kids in the bottom reading group probably aren’t. This offends people’s sense of freedom and justice, but it is the reality that we live in.

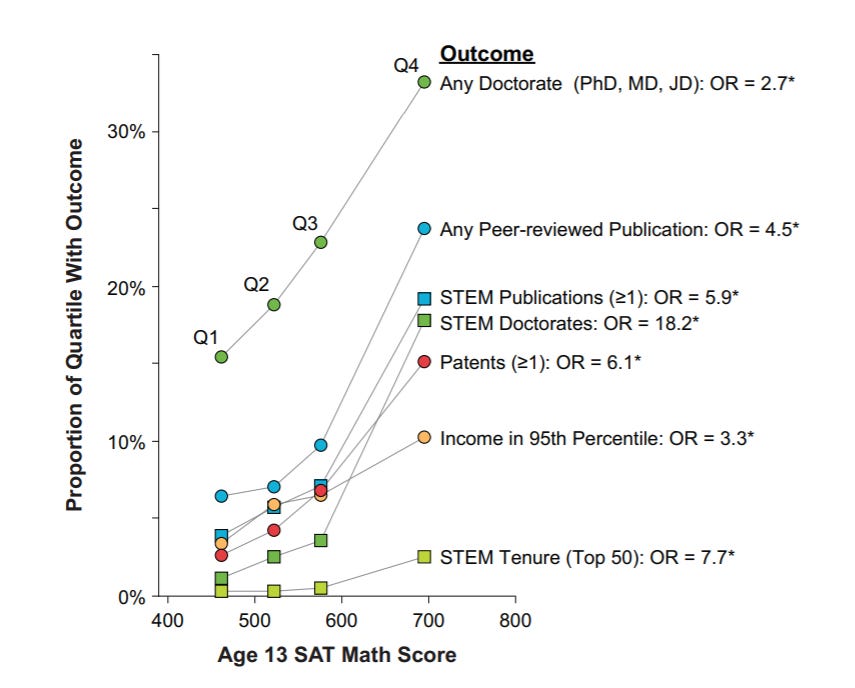

The persistence of relative academic performance is remarkable. Standardized test scores collected at the age of thirteen are strong predictors of not just future high school and college educational performance but adult outcomes like academic career milestones and economic position, even after adjusting for parental income:

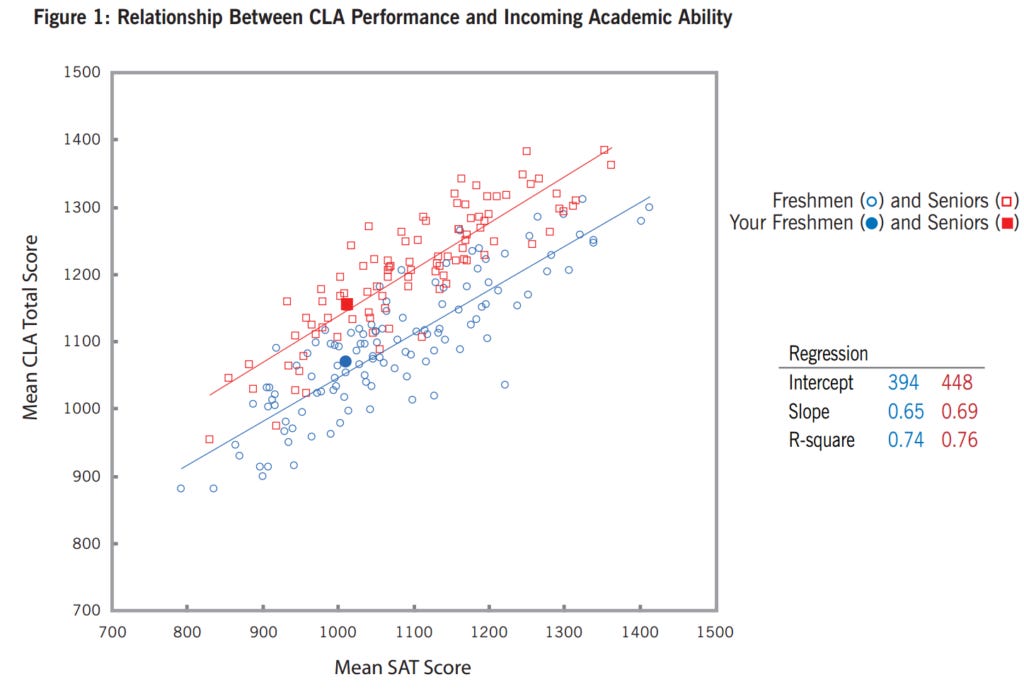

If you’re a college administrator, what is the best predictor of how your incoming freshman class will perform as college seniors on a standardized test of college learning? Their performance on the SAT as high school seniors, of course. What else?

The distance between the blue and red regression lines represents absolute learning, how the students at the average college have improved over the course of their college careers7. The relationship between the variables, the tight grouping and angle of the data pattern shows that the relationship between the mean SAT score your students got near the end of high school and the mean Collegiate Learning Assessment8 score your students got near the end of college is quite strong. If your admissions process screened out weaker students coming in, your reward was stronger students going out. Obviously. Were individual student outcomes as elastic as people in the policy and politics world assume, you wouldn’t predict this kind of relationship. Students would go to different colleges and the supposedly dominant environmental variables would overwhelm prior advantage to create very different relative performance. That simply doesn’t happen. What, you think Harvard is going to risk its reputation on something as illusory and intangible as “school quality”?

If you’re an administrator at a college that is not selective (the kind of college I went to), you can take heart in the fact that even though your student body is likely on the lefthand side of the plot due to low incoming SAT scores, you can move your institutional average northwards over the course of a class’s career by producing absolute learning gains. Your students will leave knowing more than they did when they came in. But what you probably can’t do - what there’s simply no reason to believe you can do - is teach your students so well that they catch the student bodies of the schools on the right half of the plot. Because those students not only started out ahead, they’re learning at college too, inconveniently. There is no evidentiary basis for the conventional wisdom that schooling can change the performance of students relative to their peers, with any consistency at anything like scale - and it is change at scale that would be required to “fix our education system.” Wonks should perhaps ask themselves why they believe otherwise.

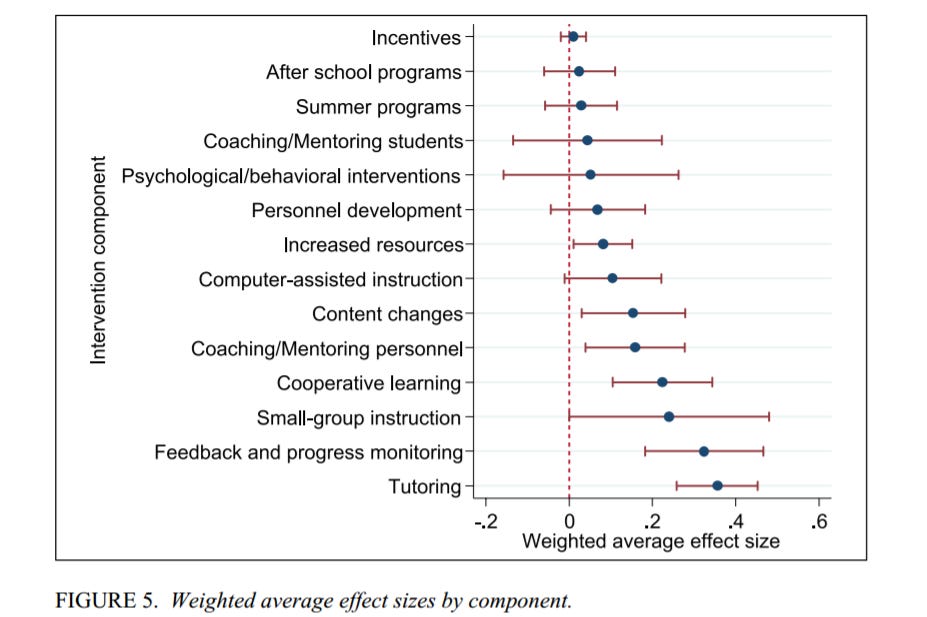

Many quantitative educational metrics prove resistant to the impacts of teaching and schools. Consider this large meta-analysis of techniques attempting to help low-SES students succeed.

The dots are the mean weighted effect sizes9 of a given intervention. The red lines are the error bars, which help to tell you if the observed effect is statistically meaningful. If the red line cross the vertical dotted line, we can’t say with statistical confidence that the effect is greater than zero. Which means that of 14 major studied interventions only 6 have statistically meaningful effects at all, and of those 3 are less than .2 of a standard deviation, which means they have very limited practical effects10. You’ll get a better picture of how often education research fails to identify any meaningful effects from interventions by looking at a similar graph of the means and error bars of individual studies:

You see how almost everything is clustered right around zero? Most things we try in education simply don’t do anything. This is reality. Why have vast expenditures in classroom technology so often had disappointing results? Why does randomly distributing computers for children to use at home make so little educational difference? There are so many cases where interventions that seem intuitively plausible turn out to have no or little effect in the real world. If you believe the standard liberal story of children as undifferentiated academic masses whose outcomes could be easily improved with a little want-to and ingenuity, this is perplexing. If you listen to research, experience, and common sense, you’d recognize that it’s precisely what you’d expect in a world where everyone is not equal in academic potential.

You might say “but that’s absolute learning, not relative.” But consistent absolute learning for the academically disadvantaged is the only tool through which relative changes could be achieved at scale, right? The poorly-performing students need to make academic gains that the higher-performing students don’t. The problem is that if you found such a tool - if any of this worked - it would be hard to imagine that parents of high-performing kids would accept not allowing their children to take advantage of it too. (If you want to close the Black-white achievement gap, the most reliable way would be to outlaw white students from going to school for several generations.)

If environment dictates everything, then school quality would be immensely consequential. If school quality is a real, stable, and meaningful property, and the environmentalists are right about educational outcomes, then switching schools should have a dramatic effect on how a student performs in the classroom. But what parents typically find is that their child slots into the distribution just about where they were at the old school. The research record provides a great deal of evidence in this direction too.

For example, winning a lottery to attend a supposedly better school in Chicago makes no difference on educational outcomes. In New York? Makes no difference. What determines college completion rates, high school quality? No, that makes no difference; what matters is “preentry ability.” How about private vs. public schools? Corrected for underlying demographic differences, it makes no difference. Parents in many cities are obsessive about getting their kids into competitive exam high schools, but when you adjust for differences in ability, attending them makes no difference. The kids who just missed the cut score and the kids who just beat it have very similar underlying ability and so it should not surprise us in the least that they have very similar outcomes, despite going to very different schools. (The perception that these schools matter is based on exactly the same bad logic that Harvard benefits from.) Similarly, highly sought-after government schools in Kenya make no difference. Winning the lottery to choose your middle school in China? Makes no difference. All of this confirms anecdotal experiences. Did kids you know go from failures to whiz kids when they moved to a different state, a drastic change in environment? No, of course not. Because they’re the same kid.

Teacher quality perhaps exists but likely exerts far less influence than generally believed. There is no such entity as “school quality.” (I have addressed the charter school shell game at considerable length here.) There is the underlying ability of the students in a school that produces metrics that we then pretend say something of meaning about the school itself. That’s it. Zoning doesn’t make kids perform poorly by keeping them out of the best schools. Zoning creates the impression of the “best schools” by keeping out the kids destined to perform poorly.

Late last century France created an artificial cutoff date for conscription into the military. The result was a sudden influx of students into higher education; men who would have spent years in the military instead spent them going to school. But it not only made no difference in terms of wages or employment, it made almost no difference in the amount of people graduating from higher education. Conscription was screening out the marginal students from attending higher education. But removing the screen didn’t make those students any less marginal. If school matters most, going to more school (or whatever quality) should have a demonstrable impact on students. At a vast scale, in one of the wealthiest and most developed countries on earth, it did not. It simply made no difference.

Meanwhile constantly cited explanatory mechanisms, like class size, aren’t necessarily explanatory at all. Calls for smaller class sizes are ubiquitous because they are one of the few interventions endorsed by both neoliberal ed reformers and the teachers unions who are their enemies. But the quantitative effects of class size has been a research obsession for at least 40 years, and yet there is no real consensus on what exactly works, for what students, in what contexts. Claims of a small class size advantage routinely carry extensive lists of provisos, such as saying that it’s necessary for physical classroom space to not shrink along with number of students, the kind of requirement that makes implementing these efforts at scale a policy nightmare. Nor is there consistency between different studied groups; for example, at the university level class size effects vary wildly depending on who you’re looking at.

The famous Tennessee Project STAR study from the mid-80s helped set the national conventional wisdom that class sizes have major impacts on student performance. But the STAR study 1) only placed students aged 5 to 8 in smaller classes, particularly troublesome because environmental impacts on academic outcomes of children tend to fade over time, 2) was conducted in a state that was a significant negative outlier in all manner of educational metrics, undermining our confidence that its results could be generalized, and 3) has met with consistent skepticism about its randomization processes. Teacher-quality advocates Steven Rishkin and Eric Hanushek pointed out in 2006 that only 40 of the 79 small-size kindergarten classes outperformed the regular classes at all. A ten-year follow-up, again represented as a victory for small class sizes, found a significant increase in passing the state standardized language arts test for 8th grade students who had attended small classes - statistically significant, that is. The advantage of those who had attended small classes earlier compared to those who had not was 52.9% to 49.1%. I will leave it to you to decide if that is practically meaningfully. Either way, we are left to decide whether these results are large enough, consistent enough, and scalable enough to be worth the enormous additional expenditures this type of intervention would require at the national level.

It’s also perfectly easy to find studies that find that class size advantages that are not remotely efficient give the expense associated or which find no meaningful small class size advantage at all. In 1995 Karen Akerhielm found performance boosts from reducing class sizes… by 10 students, a decrease with a financially massive cost at scale… of 5%… and only in history and science. In 2000 Stanford’s Caroline Hoxby found no statistically meaningful effect at all. Sathish Kumar does me a solid by providing a scatterplot in his 2019 study on student performance predictors:

Again, if environment matters most or is all that matters, we would absolutely expect a major and consistent effect from class size. If intrinsic ability predominates we wouldn’t. Where is the evidence pointing? The constant churn of new conventional wisdom about this topic over decades is not encouraging. Should we have smaller class sizes? I believe so, yes. We should have smaller class sizes for the comfort of students and superior working conditions for teachers, not because of uncertain benefits in quantitative metrics. I will return to this theme below.

The lack of a class size effect is one of many dogs that don’t bark, intuitive explanations of academic outcomes that don’t actually work out. Another is grit, or a student’s capacity for perseverance in the face of challenge, which a (88-sample, ~65,000 subject) meta-analysis finds is vastly less important than stated in the media. (There is an awful lot more grit skepticism out there if you’d care to look.) If you want your child to succeed in school and you can choose to give them more grit or a higher IQ you’d go with IQ 100 times out of 100. “Classes should be smaller so teachers can give students more attention” and “it’s important to have perseverance and work ethic” are deeply intuitive stories about education that may be true in the broader sense. But the notion that they will reliably improve quantitative educational metrics is demonstrably false. (It’s not even clear if grit can be learned.) Why? Because they’re premised on the notion that the outcomes of individual students are deeply malleable. But if relative student outcomes were so plastic, you would expect them to be changing constantly throughout a student’s life, and for individual students to be forever trading places in relative metrics. That’s not what happens.

Nor does pre-K, the most commonly cited cure-all for educational inequality, seem to have much effect, although as you’d imagine the topic is very contentious. There’s been a lot of positive findings in this space that have then been challenged or walked back. For example, the well-known Campbell et al Science article looking at the health improvements (and knock-on effects) from early child care programs found robust gains, and this was reported all over the place. Unfortunately, this finding was severely undermined by the immense attrition of the sample (40% of males!), a problem that could not have been identified in the original paper because the information necessary to know literally wasn’t published there11. To me it screams of the optimism bias in this type of research. I’m not accusing anyone of deliberate research fraud. I am saying that people who research pre-K programs tend to have an immense personal investment in them working, and this unconscious bias inevitably colors their research. And it’s not like what’s actually in the research record is so great anyway. Duncan and Magnuson, 2013:

(Why would the reported effects of pre-K programs shrink over time this way? Because we got better at doing studies.)

Relatedly, it is common for those on the broad political left to assert that these static student outcomes are the product of America’s high income inequality and relatively high child poverty. This is not anything intrinsic to the kids themselves, in other words, but rather a consequence of economic disadvantage. Unfortunately, liberals tend to vastly overstate the impact of socioeconomic status on educational metrics. Yes, a generic SES effect exists in K-12, but it varies widely from context to context, and it does not have nearly the explanatory power some liberals assign to it, given that they speak as though it explains essentially all of the variation. Nor do dramatic changes in a family’s wealth seem to have much measurable impact on the outcomes of individual children within those families.

College attendance is undoubtedly influenced by SES, but it is unclear how much of this is through the educational mechanism itself. Claims that the SATs merely replicate the income distribution float around social media constantly, but it’s very easy to produce a correlation coefficient that shows the relationship between the variables of SES and SAT score. And a ~150,000 score sample shows a coefficient of .25. Is that meaningful? Sure. It’s not nothing. But it means that the large majority of the variance is not explainable by SES. Meanwhile the most regularly cited reason that better SES would raise SAT scores, test prep, does not have a strong evidentiary basis in the research record. I regularly encounter pushback on this issue, but the data seems fairly clear to me: Powers & Rock 1999, Briggs 2001, McGahie et al 2004, Griffin el al 2008…. All show little or no effect on the outcomes of standardized tests from coaching. The story liberals want to tell about the SAT and similar tests is a mirage.

It is also common to speak imprecisely about differences in the SES status of families vs the expenditures of the schools that serve those families, and assumptions about which schools have greater financial resources are frequently incorrect. (For the record, high-poverty and high-racial minority schools actually receive significantly more per-pupil than whiter and more affluent schools, but there is a lot of complication there.) Peer and neighborhood effects are frequently endorsed as explanatory, but they don’t tell us much of what we want to know. An analysis considering segregation, neighborhood effects, and the SES of schoolmates still left 90% of the racial achievement gap unexplained, suggesting that these factors have limited salience for any population of students.

In 2015 Eric Turkheimer looked at pairs of Swedish siblings who were raised in different home environments to determine the influence of parent education (which is a strong proxy for income as well). This allows for better understanding of the influence of parenting and home environment while lessening the confound of genetic difference.

Turkheimer argues that this demonstrates a strong effect from being reared by parents with significantly greater education. But the chart can be a little misleading if you don’t apprehend the scale of the Y axis. The difference between 0 step-ups and the largest step-up is 7 points of IQ. (If IQ gives you the willies, remember that it correlates quite strongly with years of education and think of it in those terms.) 7 points is not nothing, and is consistent with what I’ve always said, which is that there is some environmental impacts on academic and cognitive outcomes. But consider what it means that the massive environmental difference of separate families can only muster an additional 7 points of IQ. And of course placing students into an entirely different familial environment is not a practical means of fixing things. Meanwhile the Wilson effect suggests that the importance of the family environment on cognitive outcomes fades over the course of childhood. Note too the possibility that both SES and educational outcomes are genetically influenced, in which case changes to family SES would not necessarily result in changes to educational outcomes.

The left further claims that a robust social democratic state could ameliorate these problems and create educational movement. But as I recently discussed, Denmark’s vastly more redistributive social state and far lower socioeconomic inequality do not result in any greater intergenerational educational mobility at all. It’s true that intergenerational mobility is not the same as the type of movement in relative measures I’m talking about, but as I suggested above since parent and child are correlated in educational outcomes for both any individual student and their peers a lack of movement in intergenerational mobility would suggest a lack of movement compared to peers also. And the bigger question looms: if everything Denmark is doing to influence the environment of its citizens has such little impact on their educational outcomes, what more could we realistically do?

Is my claim here that environmental factors don’t contribute to educational outcomes? No. There are consistent and demonstrable impacts from all manner of influences that might be considered environmental. For example, premature and low birth weight babies frequently go on to struggle academically as older children. The negative cognitive effects of lead have perhaps been somewhat overstated but are nonetheless real. The issue is that these factors are often real but very small. Access to legal marijuana does negatively impact the academic performance of college students - by less than a tenth of a standard deviation. Still, the aggregate of many small environmental influences can be very meaningful. I’ve already said that I believe the racial achievement gap is the product of the profoundly different environments Black children live in on average, and these environmental changes are far more complex and multivariate than the SES differences that do not adequately explain the achievement gap. The problem is that it is far harder for policy to change a vast number of tiny influences than to change one big influence. Nor is there any guarantee any given environmental influence can be changed. As neonatal medicine becomes more advanced we will have more surviving preemies, not fewer; we could do a massive lead cleanup, but the political barriers are significant for debatable gain; we are deciding as a culture that the costs of criminalizing marijuana are higher than the benefits of doing so. Etc. Environmental does not necessarily mean malleable.

Again, the more interesting dynamic to me than the existence of an achievement gap is that within the category of poor Black kids and rich white kids there are both those who struggle terribly and those who succeed at the highest levels. It’s far easier to explain why a poor Black student and a rich white student have profoundly different academic outcomes, given the vast differences in their life experience and environments, than it is to explain why two equally poor Black students who live in the same neighborhood with the same general family compositions and attend the same school would have equally different academic outcomes. But this happens all the time. Dr. Carl Hart, to pick a random example, escaped from poverty and crime in Miami Gardens to academic stardom where many of his peers did not, despite all manner of similarities in their backgrounds. Why? Pure environmentalism can’t possibly resolve that question. But this kind of example and our consistent research observations fit perfectly with the belief that environmental factors influence the most determinative factor of all, some sort of innate or intrinsic ability of whatever origin.

Many will reply to this essay by saying that just because something is innate that does not mean it is unchangeable. This is true. And I haven’t and wouldn’t say educational outcomes are immutable. The question is, what can we do from the perspective of the system that would work to “fix our schools,” to achieve the (remarkably vague) education-driven social outcomes politicians and policy types want?

The kind of intervention we would need has to

Have meaningful influence on academic outcomes where so many have failed

Be reliable, replicable, and scalable to a vast degree

Cost little enough that the administration of this intervention is economically and politically plausible

Somehow apply only to the students who are struggling or any subset thereof, and not to the students who are already flourishing, or else allow for us to prevent the parents of flourishing students from accessing this intervention for their own kids, lest we merely advance the whole student population forward but preserve the relative distribution that creates professional and monetary rewards under meritocracy.

Simple.

I quote James Heckman, the same James Heckman who co-authored the Denmark paper and the problematic pre-K health outcomes paper. Ten years ago he wrote

Gaps arise early and persist. Schools do little to budge these gaps even though the quality of schooling attended varies greatly across social classes…. Gaps in test scores classified by social and economic status of the family emerge at early ages, before schooling starts, and they persist. Similar gaps emerge and persist in indices of soft skills classified by social and economic status. Again, schooling does little to widen or narrow these gaps.

I would argue that, in the years since, the evidence that academic hierarchies are essentially static has only grown.

So what’s the origin?

All of this is consistent with the simple observation we all had when we were kids, which is that some of our peers were better at school and others were worse, and that their relative placement within performance band didn’t change much. Admit it: you thought there were “the smart kids” in school, whether you classified yourself among them or not, and that classification was justified by performance again and again until you graduated from high school. Did one or two of them fall down the rankings because their parents got divorced or they started doing drugs? Sure. But as a class, they stayed the smart kids the whole time. Because to a large degree when it comes to school we are who we are. If you think I’m disparaging everybody else, well. I wrote a whole book about why we should care much less about who’s smart.

Now it seems to me that the most likely, most parsimonious explanation for all of this is genes. I’m not going to try and summarize the entire field of behavioral genetics/social genomics, nor am I qualified to argue in its defense. But there is a very large body of research that lends credence to that idea. (And, as I have said, a very large body of criticism against it.) Again, I consistently find it hard to understand how genetics, which influences absolutely every other part of who we are as organisms, would have literally no impact on cognition and the mind. That this idea is not just prevalent but rigidly enforced as a matter of social dogma is baffling to me.

But I am not at all a genetics partisan. I have always said I am mechanism agnostic when it comes to why intrinsic academic aptitude exists. Any manner of explanations could apply to why some of us are intrinsically better at school than others. I am however quite partisan about the fact that intrinsic academic aptitude exists, because both overwhelming evidence and common sense insist that it exists. If the genetic explanation is conclusively disproven tomorrow I will not suddenly start believing that we are all 100% the product of our environments and our teachers, as many liberals believe. I will instead say “OK, what’s the mechanism creating innate ability then?” Because that is the only sensible approach given the evidence. The alternative is the hand-waving mysterianism of referring to shadowy hidden variables no one has thought to measure in the past 150 years of education research.

The first step to answering the question of why this happens is to acknowledge that it happens, the overwhelming evidence for a construct of innate academic ability.

Policy Implications

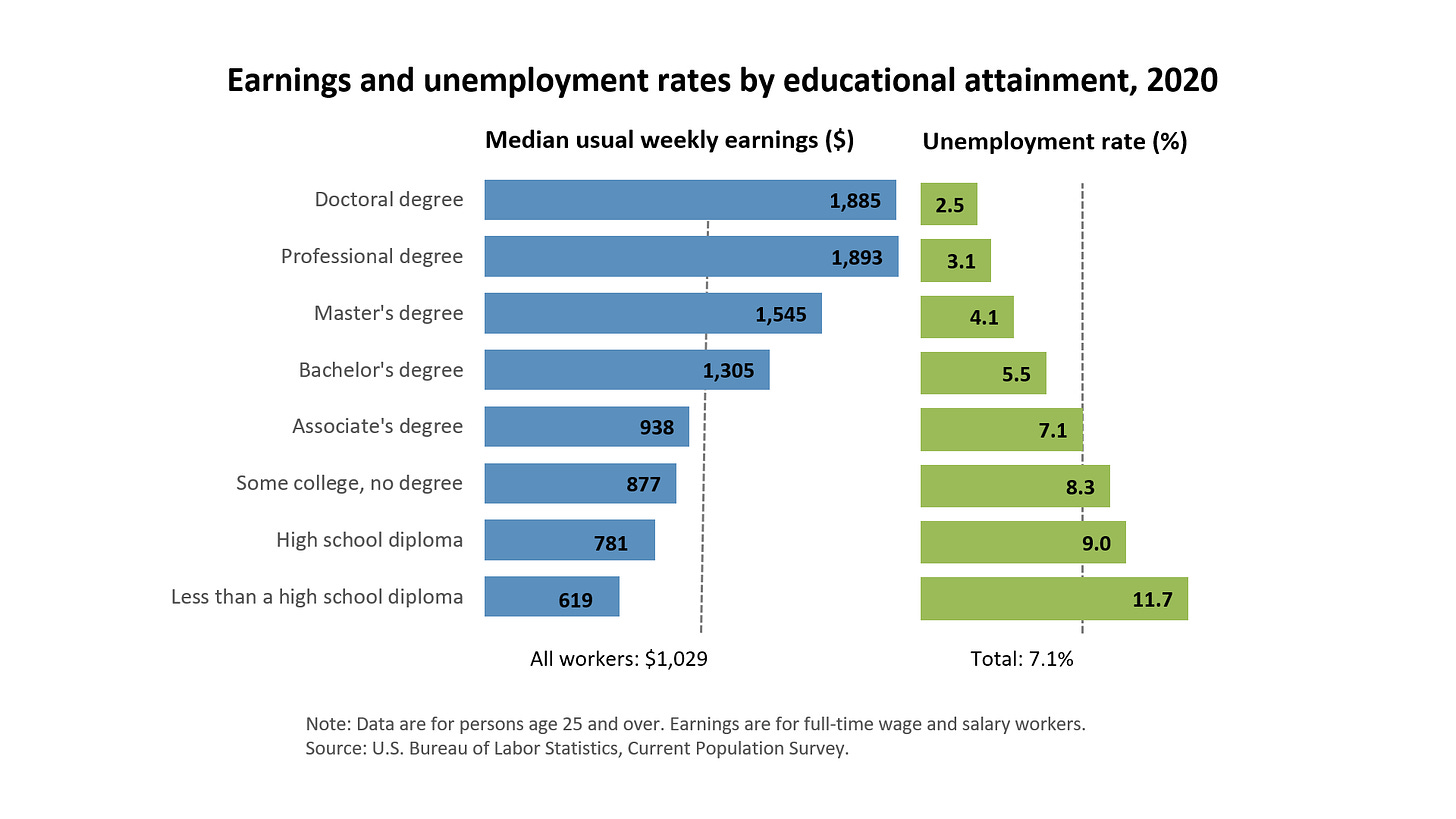

Education will never be the way we create economic security for all because, as I discuss at length in the book, it can’t be. There are all sorts of reasons for this that don’t even depend on belief in innate aptitude. Every president going back at least as far as Ronald Reagan has claimed that education is the key to solving our economic problems, but how this is going to happen is remarkably undertheorized. The general thrust of policy and rhetoric seems to be to send more and more people to college; after all, there is a wage and unemployment premium associated with a degree12. But I’ve already linked to the NBER paper that shows that the college wage premium is inversely proportional to the number of people with a degree in the market. (As common sense also suggests.) Which means that if we give everyone a degree then the market advantage of that degree will disappear. When you go on the labor market your degree is valuable because it shows how you are unequal from your competitors who don’t have one. If they all have one too (equality!) there’s no longer that inequality in your resumes and thus no positive inequality in your desirability as an employee. What will follow is an acceleration of the credentialism arms race, exacerbating the recent ludicrous increase in the number of masters degrees.

The Mark Zuckerberg vision of every poor kid becoming a Stanford-educated coder who gets a great job in the Valley is a cruel fantasy. It’s a shame that billionaire money has made that the target of our entire educational policy apparatus!

Some people say our goal is to give exceptional children who are trapped in restrictive environments a chance to excel and rise up from the ranks. But exceptional children are exceptions, and rising up from the ranks leaves the ranks behind. This kind of increased mobility does very little to address broader inequality or poverty. Also, as I keep insisting, any amount of mobility is zero sum from the perspective of the system. Whether you’re talking about class rank or income quintile, for everyone who moves up one rung on the ladder someone else goes down. As much fun as it would be to completely flip the distribution so the rich become the poor, mobility does nothing to actually squash the space between rungs, nor does it improve the living conditions of those on the bottom, so it’s of no use to us. An individual working their way up rationally desires mobility. Society, on the other hand, should want to squash the distance between bottom and top and make sure those on the bottom have security, comfort, and dignity.

If I’m correct, and there’s some innate quality of academic ability that individuals neither choose nor control? I would argue that this simple and empirically powerful observation breaks the liberal project completely.

I am constantly told that I fail to understand that what we “really want” is equality of opportunity, not equality of outcomes. I don’t know what we want, but equality of opportunity is certainly not what I want. (Like Marx and Engels I don’t actually view true equality of outcomes as a coherent political goal either, but that’s a discussion for another time.) Depending on your point of view, equality of opportunity would either amount to running in place or even cause more harm than good even in an idealized world. Besides, equality of opportunity is a nonsensical goal. For opportunity to be really equal in a meaningful sense, we would have to have all of the same natural endowments. After all, if you were present when God made you and He gave you significantly worse talents then someone else, you’d very likely say that your opportunity was not in fact remotely equal. And if everyone had the same endowments and the same opportunity otherwise, everyone would ascend to the same station, and we’re back to equality of outcomes. Of course everyone does not have the same endowments, including in terms of academic ability, so equality of opportunity is unachievable no matter what sort of society you build.

Is there no hope? Of course not. We know exactly how to help people. Observe.

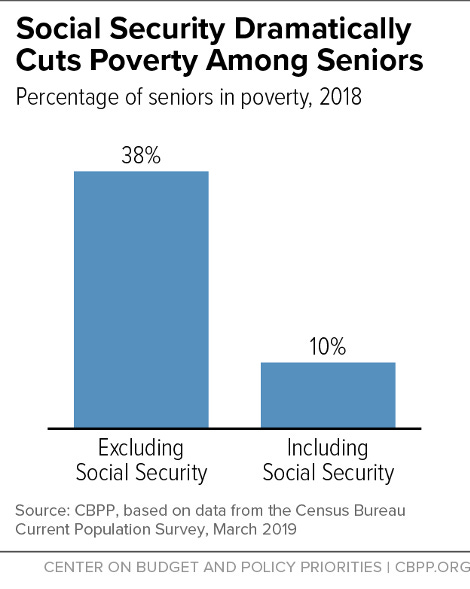

Voila! When we realized that our elderly poverty rate was a national disgrace, we didn’t send our old people back to school like Rodney Dangerfield. We gave them money. Rather than engaging in meritocratic voodoo with education, just tax rich people so they have less and cut checks to poor people so they have more. Remember the Denmark paper above, which shows that Denmark’s far more redistributive social state has no more intergenerational educational mobility than the United States? Heckman seems to think that this is a knock on Denmark. My own response is to say… so what? Denmark has the lowest socioeconomic inequality in the OECD and crazy low poverty. In other words, life in Denmark is pretty sweet even for the people who fail in the education game. Isn’t that vastly more humane than creating this Nietzschean hellworld Lord of the Flies competitive educational system, throwing chum in the water, telling kids who have substantially different academic gifts that their lives depend on the outcome, and then giving some of the struggling kids coupons for 10% off at the Scholastic book fair and calling that reform? Reform is not cutting it, folks. If academic talent is real, it can’t.

Why do you think those billionaires keep pouring absurd amounts of money into school reform, despite decade after decade of failure? Because they know the alternative is to take some of their money and give it away.

Sometimes I will go looking at Wonk Twitter to see what the white boys there are cooking up in the education space. You know, your Vox crew, your 538ers, your Slateys, your think tankies, your non-profiteers, your Nate Silver reply guys, your TED graph fetishists, your various dweebies. It’s always a remarkable exercise in fixating on the outcome you want without ever once considering your basic apprehension of the system. They look at decade after decade of education research and reform failing to move the needle in education metrics, they see the subsequent failure of the system to produce any more equality or mobility or utility, then they push their glasses up their nose and go “perhaps if we tweak the Earned Income Tax Credit.” Maybe they should get in touch with their inner 10 year old and arrive at the right answer: some kids are smarter than others, and that can’t be changed, but the less smart ones are still just as worthwhile and valuable as people as the smart ones, so let’s rescue them from economic immiseration by giving them money instead of, like, inventing a better graphing calculator or blaming a teacher who happens not to have the ability to reach into the skulls of her students and directly rearrange their neurons.

Imagine for a moment that you’re a rational person. You look at two options before you. You can look at the Scandinavian social democracies, observe that they took money from rich people, grew the public sector and built sovereign investments, and gave money away in a variety of clever ways, then note the many metrics of quality of life in which they flourish. Then you look at America for the past 50 years. You can look at effort after effort to “fix” education, all in service of some vague desire to improve student outcomes for economic benefits that are actually quite inscrutable when you think about it, and you can see how all of this money and expertise and time and brutal pressure on kids went up in a cloud of smoke, except that actually a ton of the money got shunted to some of the most rapacious corporations and individuals in our economy, and what we have to show for it is no progress but a broad bipartisan mandate that we should fire a lot of underpaid civil servants when we have essentially no reasonable argument that they’re to blame, because we’ve got to do something that doesn’t entail taxing the rich. Which system would you choose?

Now those wonk boys mentioned above, if they’re feeling cheeky, will say some version of this if they come across this post: if all of this is true, just slash funding to schools and treat them as daycare warehouses to keep kids safe until they turn 18. This is indeed a rational response, if you believe that the purpose of school is to change quantitative educational metrics. But the obsessive focus on these quantitative indicators is actually fairly new. For several decades after desegregation most students hardly took any standardized tests at all. The college-ready few would take the SAT. State-mandated standardized tests were rarer and shorter and less frequently occurring. International comparisons barely existed, and in those that did, the US generally sucked, but nobody noticed.. Parents may or may not have kept track of grades, and the ambitious students may have fixated on their class rank, but huge numbers of students and parents went through K-12 with hardly any notion of how the student stacked up relative to peers whatsoever. For the record, many would identify this period as the period of America’s greatest dominance.

Does that mean that the conditions under which our children learned didn’t matter? Of course not. It mattered because students and teachers are human beings and we should strive to make their lives at school more comfortable, fulfilling, and safe. There are all manner of virtues that we can hope to encourage in our schools and our students, ones for which there are no standardized tests - community, open-mindedness, creativity, respect for difference, patience, perspective, individuality, freedom. Those things can be cultivated, but teachers and administrators can only pursue them if they aren’t spending every waking second of their lives trying to juke artificial stats that will only remind us again and again that some people have intellectual gifts that others just don’t have. A more humane social contract with greater redistribution and a schooling system that prizes humanistic values rather than quantitative metrics and which helps students who are not academically inclined to find a career niche can all be achieved. Dramatically moving students around in the quantitative performance spectrum cannot be achieved. It has never been achieved.

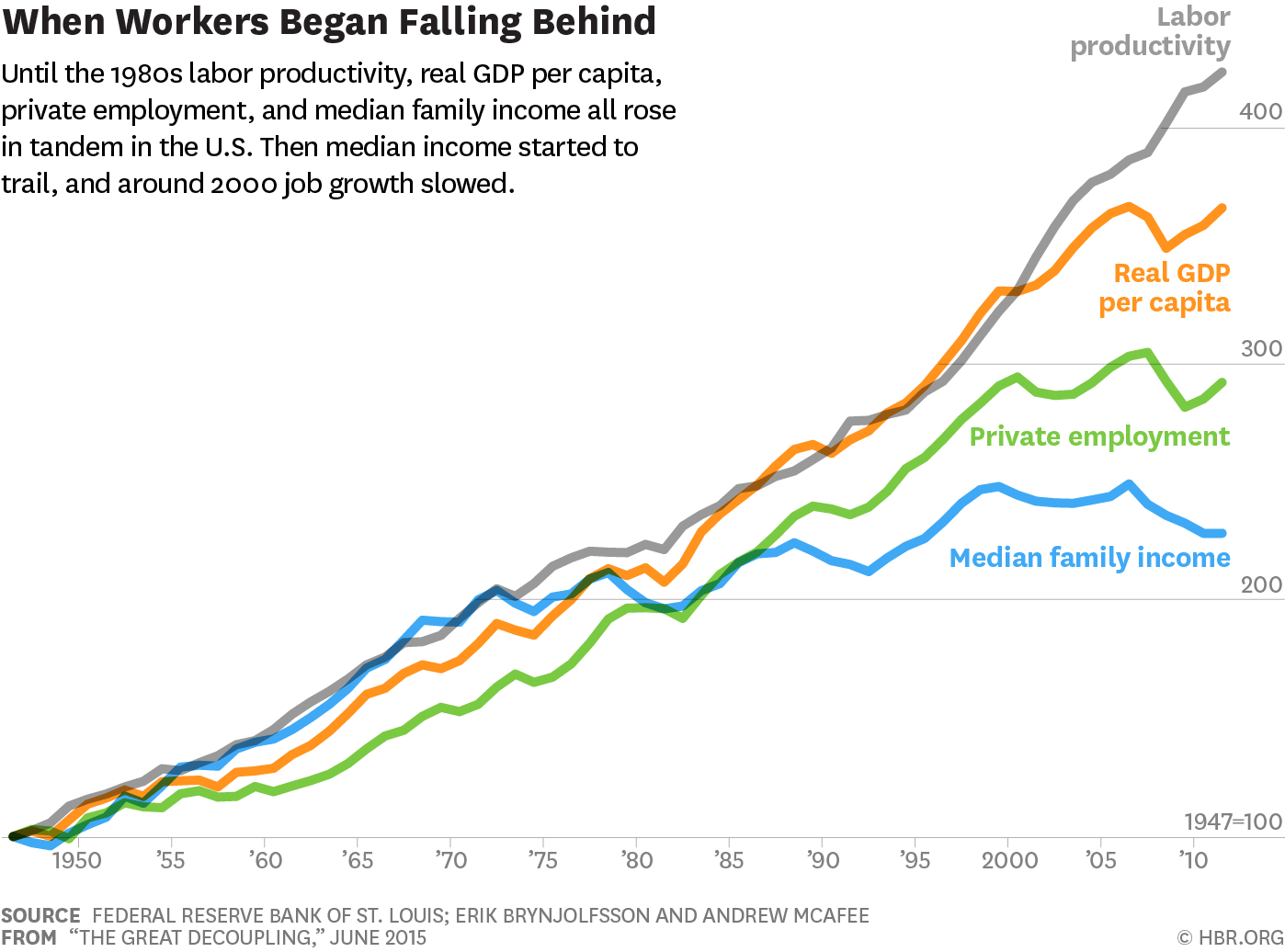

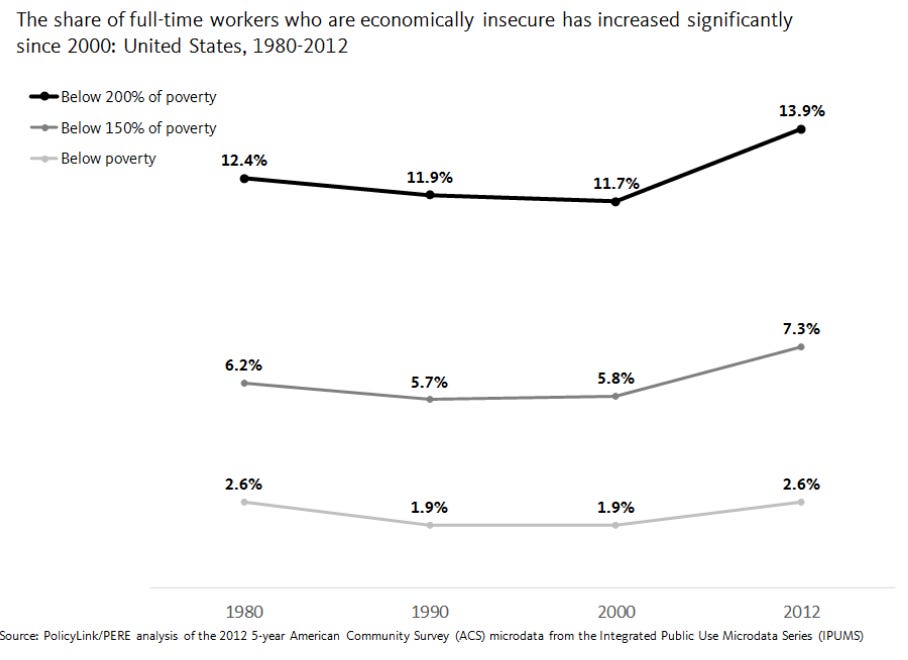

Look. We’ve become a vastly more educated nation over the past few decades. What has that meant for working age poverty rate (the relevant metric), inequality, and the decoupling of income and productivity?

Not great! Maybe we should give people money instead. Fun fact: the fasting growing occupation in America is home health aid. It doesn’t require a college education. The median wage is $27,000 a year. Right now our system’s message to all of those people who will spend their days helping keep our elderly alive for poverty wages is, well, hey. Should have done better in school. Maybe the first step in doing better for them is recognizing that most of them never had a choice.

If you’re really dead set on education as the key to improving the economic fortunes of the disadvantaged, and you don’t think we can or should redistribute our way to a more just and equal society, and you’re fixated on moving kids from the bottom quartile of academic performance to the top, then what can we do?

Nothing.

Or, go in the other direction and insist that the 4+ pages of engagement with the genetic science that got cut stay in.

That was one of the most repeated criticisms of the book, not enough engagement with the science, and I could have avoided it if I had stood up to a publisher’s requested edit. Ugh. (I probably would have lost the argument no matter what.)

Realistically speaking the provocation of the genetic argument helped sell the book in a tough market.

I concede that this is unproven.

If only we could have predicted that flooding any given labor market with new applicants would inevitably worsen the employment prospects for everyone in that market. But sure, learn to code.

Suppose we held a jumping competition. We would expect to find, and in fact find in real life, significant variation between individuals. (Because not everybody can jump as high as everybody else, a reality we just accept as a fact of life.) And most would readily concede that intrinsic ability play a role in this, as they do in all athletic abilities. We were not all born to run at the same speed. Now let’s say, for some reason, that we gave some of our participants weight belts that weighed them down, and others extra-bouncy shoes.

It would not surprise us to find that the average person with a weight belt jumped less high than the average overall, nor would it surprise us that the average person with bouncy shoes outperformed the overall average. This is the influence of the environment exerting itself. But we would also find that there is variation within these groups, with some of the weight belt kids jumping higher than the overall average because their sheer natural talent overwhelms the negative influence of the weight belt. It’s not unthinkable that a kid with a weight belt could be the highest jumper of all; talent is powerful. Correspondingly, there will be variation within the group with bouncy shoes, and some poor souls will finish well below average despite their advantage; a lack of talent is also powerful. The key thing to observe here is that it is perfectly consistent and sensible to believe that between-group differences are the product of the obvious environmental differences while within-group differences are partially innate.

In the analogy of course students with weight belts are poor Black students who suffer under their environmental burdens and the students with bouncy shoes are affluent white students who benefit from their environment. And as in our simple analogy environmental variation (the inequalities in living conditions between races in American society) can cause between-group differences (the racial achievement gap) while the observed variation between individuals is significantly shaped by innate potential. It is a common hobbyhorse of mine to complain that American educational research and policy is obsessively fixated on between-group differences like racial and gender gaps and remarkably uninterested in within-group differences, despite the fact that the latter would ultimately explain what makes educational (and economic) mobility happen.

I am a longtime skeptic of the narrative of Academically Adrift, the 2011 book that argued that college students aren’t learning, principally because the same analysis was performed with a larger and more representative sample and found robust average learning at colleges - absolute learning, that is.

This test was the subject of my doctoral dissertation.

Small group tutoring looks pretty good! I mean, it’s less than .4 SD, but in education research it’s a strong effect. Why is there not a big national movement to institute small group tutoring for low-SES students at public schools? Because unlike charter schools or wasteful ed tech expenditures it does nothing to advance the Silicon Valley ideology that controls the think tank industrial complex, which is the most powerful force in education at the national level.

In fact they did not report the initial sample size, which is frankly unbelievable for published work anywhere, let alone in Science.

https://youtu.be/OXj8mtUsyt4?t=60

Great post, Simpsons all over this in 1990.

I’m interested in what this means in terms of human capital. Is human capital only a thing in the absolute sense, that in aggregate humans gain knowledge and skills over time, especially in schools? Or are there relative accumulations of human capital, too?