Education Doesn't Work 3.0

a comprehensive argument that education cannot close academic gaps

This is the third iteration of my longform argument that the relative position of students in the academic ability spectrum (that is, the rank order of students as determined by quantitative educational metrics) is remarkably static over time, even in the face of massive spending and intense intervention, and that this persistence fatally undermines modern assumptions about schooling, its purpose, and its potential. The first iteration of this post is here and the second is here. Though large pieces have been preserved, this work is mostly new, with at least 10,000-12,000 words of new material.

In my PhD years, I went to a cookout on a warm spring day. Many of the graduate students and faculty members had brought their families with them. I was chatting with a PhD student from another department, the spouse of one of the many grad students from China who attended Purdue. She was talking about her older son with obvious pride, describing his achievements in his robotics club, how well he always did in math. And then her younger son ran by, and she said, offhand, “This one, he is maybe not so smart.”

I was taken aback and wondered initially if maybe something had gotten lost in translation. But over time I thought about that moment and came to see it not as a cruel insult, but as a refreshing piece of candor. There was no reason to think she loved her younger son less. She simply accepted that he had different strengths than her other son. Had she said that her son didn’t have an artist’s temperament; had she said that he would never be an athlete; had she said that he didn’t have an ear for music— I never would have thought twice about it. It’s only with intelligence that we have such massive hang- ups, only intelligence that we treat as the sole criterion of someone’s worth.

- from the introduction to my first book, The Cult of Smart

For some time now, I’ve been arguing for a perspective on the value of education that does not map cleanly onto any major contemporary ideological position, political party, or school of educational philosophy. My overall thoughts on education1 are as follows:

In any given population, the ability to excel academically (whether or not you call it “intelligence”) is, like almost all other human abilities, plottable as a normal distribution: that is, a few people will be really bad at it, a few people will be really good, and the majority will be somewhere near the middle.

Because some people are simply better at school than other people, any pedagogical strategy, practice, or method that improves the performance of the worst students will also improve the performance of the best students; this means that “closing the performance gap” between the worst and best students will only be possible if you use the best strategies for the worst students and the worst strategies for the best ones — and even then the most talented students will probably adapt pretty well, because that’s what being a talented student means. Another way to put it: if every student in America were equally well funded and every student equally well taught, point 1 above would still be true.

Resistance to these two points is pervasive because we collectively participate in a “cult of smart” that overvalues academic performance vis-à-vis other human excellences. That is, because we value “intelligence” as a unique excellence, necessary to our approval, we cannot admit that some people simply aren’t smart. (By contrast, we have no trouble admitting that some people can’t run very fast or lift heavy weights, because those traits are not intrinsic to social approval.)

In so many human domains, we’re willing to accept that some people are naturally advantaged, bound by some inherent trait to be better than others, whether it’s physical attractiveness, the visual arts, musical performance, athletics, memory, sense of direction, language learning, charisma…. We are, generally, perfectly willing to accept that different human beings have profoundly different strengths and abilities. But with education and intelligence, we’re unwilling to countenance the simple reality that some people are better equipped to succeed and some worse. It wasn’t always this way. For much of human history, that some people were simply smarter than others was accepted as a matter of course. In particular, and unfortunately, inherent group differences have historically been asserted in cognitive ability, and education was typically walled away from those who weren’t of the right class, gender, race, or station; this, obviously, was unjust and a terrible waste of human talent. In the last 50 years, however, a combination of forces2 has led us to overcorrect and embrace the opposite conclusion, that all individual people have equal ability to excel academically. This has led to all manner of ugly consequences, including blaming those who lack academic talent for their own immiseration and unfairly pinning educational failures on schools and teachers that they are not responsible for.

Our educational debates are largely useless because most people engaged in those debates assume out of hand that, absent unusual circumstances like severe neglect or abuse or the presence of developmental or cognitive disabilities, any student can be taught to any level of academic success, and any failure to induce academic success in students is the result of some sort of unfortunate error. Some tend to ascribe the failure to reach academic excellence as the result of exogenous social variables (like poverty and racial inequality) while others insist that students who have failed to learn to standard are evidence of failing schools and feckless, untalented teachers. My own perspective insists instead that as with any other kind of human ability, academic ability is unequally distributed across the population, with some destined to excel, some destined to struggle, and many destined to meet various levels of mediocrity. My belief is that this tendency is the result of some sort of intrinsic or inherent academic potential, that just as in natural talent for playing a musical instrument or playing a sport, there is such a thing as talent in school, and like all other talents, this one is not distributed equally to all people and is thus not fair.

I in particular hold these three beliefs with descending levels of confidence - the first is an empirical truth that is not debatable, the second is an obvious conclusion to draw that’s difficult to avoid given the first, the third is speculative but appears to be the most likely reason for the first two:

At scale, the relative academic performance hierarchy is remarkably static, with very few students significantly moving to higher or lower positions of educational success over the course of academic life

The remarkably consistency in student performance over time, even in the face of immense investment and relentless pedagogical and policy efforts to alter student performance, strongly suggests some individual attribute that constitutes an inherent or innate academic potential, predilection, or tendency

The most direct and parsimonious explanation for this attribute is genes

What I’m here to demonstrate today is the core empirical point that makes up the first belief: despite the widespread assumption that any student can be educated to any level of performance, in reality students demonstrate a certain level of overall academic ability and gravitate to that level of ability throughout their academic lives, with remarkable fidelity at the population level. Decades of grading data; standardized test scores; cross-sectional, longitudinal, observational, and experimental studies; along with many other types of ancillary and convergent evidence, ultimately tell the same story: education can raise the absolute performance of most students modestly, but it almost never meaningfully reshuffles the relative distribution of ability and achievement.3 We can reliably teach some (but never all) students certain knowledge, skills, competencies, and concepts that they did not possess before being taught, which we might call absolute or criterion-referenced learning. But all of these can also be assessed on a relative basis; whether students can read or do algebra or apply the scientific method are all questions that have polychotomous rather than binary answers. That is to say, students can be better or worse at the various cognitive and academic tasks learned in school, and we can assess these abilities and then assign them ranks in a relative distribution, which if our instruments are sound will almost always be normal or Gaussian - some kids will be excellent, some will be terrible, some will be in-between, and they number in each percentile will follow a predictable curve.

And here is what the data will show: rather than students moving regularly between different performance bands over the course of life, the relative distribution of students in the performance spectrum is remarkably static given the inherent noisiness of human variables. That is, the children who start out ahead in early childhood education stay ahead through the end of their academic careers, while the students who start out behind stay behind, in large majorities and with very few exceptions. There is always some “wiggle” in the distribution, and there are indeed individual students who move dramatically up (or down) in the academic hierarchy in their careers. But far, far more students gravitate to the level of their natural talent very early in life and stay there permanently. Reformers talk in terms of “unlocking potential” or “closing gaps,” but history shows the rank order is remarkably resistant to even the most sweeping and expensive pedagogical efforts. Intervention after intervention has failed to meaningfully affect the sticky nature of relative academic performance.

The brute reality is that most kids slot themselves into academic ability bands early in life and stay there throughout schooling. We have a certain natural level of performance, gravitate towards it early on, and are likely to remain in that band relative to peers until our education ends. There is some room for small-scale movement over time, and in large populations there are always outliers, individuals who move significantly up or down. But in thousands of years of education humanity has discovered no replicable and reliable means of taking kids from one educational percentile and raising them up into another.

This has profound consequences. In particular, since the neoliberal turn of the late 20th century, American opportunity rhetoric has stressed that education is the key to financial stability, mobility, and equality; from Eisenhower to Biden, American presidents have been quoted as identifying education as the key to ensuring a just economic arena for Americans. Students born in poverty and depravation can pull themselves up by their bootstraps by excelling in school, or so we’re told, and this will be the vehicle through which a strong and just economy is built in the United States. In this view, schools and teachers have large and determinative impacts of student outcomes in quantitative metrics like grades and test scores. Consequently, persistent educational failure is the fault of unaccountable schools, lazy teachers, and their corrupt unions. Hence the entire school “reform” movement that sought to discipline America’s teachers and replace a significant percentage of them with more talented and hardworking new entrants, who would sign up for the difficult grind of teaching at low median salaries for some reason or another. Then achievement gaps would close and economic justice would rise across the land.

But this rhetoric implies that most or all students have the ability to excel in school to any given degree. If instead relative academic performance is persistent, if rank order is largely preserved throughout life thanks to some sort of intrinsic or inherent academic talent, then this assumed source of social mobility is a lie. And, indeed, this is what I’m claiming today: that an overwhelming preponderance of evidence suggests that schools and teachers lack the ability to meaningfully close academic gaps. The fixation on their performance and the tendency to scapegoat them amounts to a form of blame shifting, undertaken to protect a fundamentally misguided societal notion of how widespread opportunity to doled out. We are so invested (literally and figuratively) in the notion that schools create equality and mobility that we refuse to accept the fact that they can’t despite watching child after child replicate their early-life performance throughout their academic career, year after year.

We have spent an immense amount of effort, manpower, time, and treasure on forcing students to meet procrustean academic standards, despite the fact that we have overwhelming evidence that their relative performance is largely fixed. And we continue to pour money on the problem; while spending has attenuated somewhat in the past decade, growth in the percentage of American GDP dedicated to education over time has been immense. Investing in education is noble, but only when we understand what we’re spending money on and why. At the end of this essay, I will argue that education is important, does matter, and is worth funding - but that what’s now assumed to be its primary purpose, moving students around in quantitative educational metrics, is actually what education does worst. What we need, ultimately, is a return to a holistic, humanistic vision of what school is for, and we need a robust social safety net to protect those who are not lucky enough to be naturally academically talented. What we don’t need is more magical thinking about what education can do for our kids and our economy.

What This Essay Does Not Argue

A strong affirmative case that genetics specifically influences cognition and thus educational outcomes; I think that influence is very likely, but this essay is about the persistence of relative educational outcomes and the implication of intrinsic ability, not about the potential sources of this intrinsic ability

That there are no influences on educational outcomes from environmental or familial variables; there clearly are, but the ones we can control are insufficiently powerful to meaningfully change relative student outcomes and the ones that are powerful enough to meaningfully change relative outcomes are ones that we can’t control

Race “science”/pseudoscientific racism; this essay is about the persistence of individual academic differences, not group, and such a standpoint is entirely consistent with the view that racial achievement gaps are environmental in nature, as I will discuss below

That absolute learning (that is, learning as measured against a standard or benchmark or criterion) has no value; rather, relative learning is practically and morally dominant in these discussions because only relative learning (sometimes discussed in terms of educational mobility) can better one’s economic fortunes, and it is that potential that underlies our entire modern educational debates and the reason for obsession with achievement gaps

That education can only be said to succeed if it achieves genuine equality or something like it, which is a straw man; rather, modern educational debates are caught up in the assumption that the purpose of schooling is to create socioeconomic mobility and equality (a profoundly new assumption), and the only way to achieve this mobility and equality is if students are able to reliably transcend their old position in the hierarchy, which (as I will argue) we have no reason to believe is possible.

What This Essay Does Argue

Academic performance relative to peers is remarkably persistent across the academic lifespan. Most people gravitate towards a level of relative performance early in life and remain there throughout formal schooling

The most sensible and parsimonious conclusion to draw from this observation is that there is such a thing as an inherent or intrinsic level of natural talent that is largely immutable

Contemporary American education discourse and policy assume a “blank slate” mentality in which every and any student can reach any given level of academic performance, despite both common sense and a massive amount of evidence that suggests that every individual has individual academic talent

Social, economic, and professional benefits derived from education are distributed on the basis of relative academic performance, not absolute performance, in college admissions and the job market and other sites of competition, and thus the inability to move students around in the performance spectrum has profound moral and political consequences

Given that educational outcomes are largely immutable and heavily influenced by accidents of birth and circumstance, it’s immoral for those outcomes to be used in social sorting processes that can result in a lack of opportunity and poverty, and we should build a robust and highly-redistributive social safety net to protect everyone regardless of ability

Education and schools will be healthier, happier places when they no longer feel pressure to create academic equality or economic opportunity and can return to more humanistic, holistic goals related to engendering curiosity, fostering social development, inspiring lifelong passions, facilitating creativity, and setting up a lifelong love of learning.

I Assure You, You Do Care About Relative Learning

One of the most common complaints I receive in response to my views on education is to dismiss the importance of relative learning. “Who cares how well kids do compared to their peers?” they say. “What matters is that they learn.” I’m afraid that, as intuitive as this seems to many, it doesn’t really work.

First, relative learning is ultimately just a way to put absolute learning into context. If someone has consistently scored terribly on relative assessments, this will inevitably mean that they have failed to learn much in an absolute context as well. A kid who’s in the 20th percentile in terms of GPA and state standardized test scores is a kid who certainly has not learned enough in absolute terms either. We have relative academic comparisons for several reasons, but a core one is that absent a norm to reference against (hence norm referencing) it’s difficult to interpret the results of even the best assessments. The fact that relative learning is limited necessarily implies that students are not learning enough in the absolute sense to transcend their rank order. If absolute learning was uncapped, there would be no such thing as a static hierarchy of student performance.

Second, while I am happy to concede that absolute learning happens all the time, this should not be mistaken for saying that absolute learning is easily achieved, reliable, or consistent. One of the books that has inspired me the most is Andrew Hacker’s The Math Myth, where Hacker patiently demonstrated that a remarkably large percentage of our students are not really learning abstract math to the degree required by standards, and that many who have officially passed those standards were simply allowed through via a form of social promotion. In fact, the most reasonable conclusion to draw from Hacker’s work is that many students simply are not equipped to meet those standards, that they do not possess the underlying ability necessary to succeed at that type and level of math. (The sensible thing to conclude, given how few adults actually use algebra, trigonometry, geometry, or calculus in their daily lives is that we should replace these onerous standards with broader, looser, more forgiving quantitative reasoning requirements or similar.) Anecdotal experience relayed by the large network of professional educators I know is even more stark: it’s very common for teachers of all kinds of subjects at any given age group from all manner of schools (public, charter, private, university) to admit mournfully that many, many students pass through the halls without learning anything like up to standards.

The point being that, yes, absolute learning is common, and there’s obvious and consistent generic quantitative gains associated with schooling - and certainly, kids who don’t get to go to school don’t learn much at all. But that should not be confused with some sunny “hey everybody learns eventually” conclusion. Many students learn less than they are required to by standard, and a small but persistent number learn almost nothing.

Most importantly, though, is a simple reality: the consequences of education are derived from relative performance, not absolute. Yes, there are some scenarios where the ability to perform a given skill or task is sufficient to receive some benefit regardless of relative ability; being able to drive, for example. (And a driver’s test is a classic example of a criterion-referenced exam, that is, one where there is no attempt to rank performance relative to peers and instead a focus only on the ability to satisfy the criterion.) But in the vast majority of scenarios where education is relevant, applicants of whatever type are being evaluated relative to peers. Competitive college admissions is a perfect example; the entire process is intended to determine which students are better and worse, to weigh them against each other. SAT scores are considered valuable to colleges (and in a less direct sense to society) because they are good predictors of college preparedness. But they’re valuable to students because colleges use them to decide between potential applicants, because it helps them relative to each other. Then, when they apply for jobs or to graduate school or for fellowships or other competitive endeavors, they likewise hope that their academic resumes will distinguish them in relation to their peers.

For example, consider the recent collapse of the entry-level programmer job market and the cult of “learn to code.”4 I’ve been talking about the folly of that little motto for a long time. The trouble is that, first, flooding the market with new entrants degrades the very advantages in employment rate and wages that made programming attractive in the first place - when you tell people that coding is a safe haven, they’ll believe you and try to break into the field in great numbers, meaning that there’s more and more competition, that is, other applicants who you need to prove your relative superiority to5. And second, “learn to code” suggests that coding ability is binary, like you either can do it or you can’t, when of course coding (like almost all human abilities, skills, and competencies) can and is assessed on a relative basis of better to worse. If you go on the job market, you care about your ability relative to other applicants because the employers doing the hiring care about your ability relative to other applicants.

Black students, even Black students from poverty, have been improving steadily in absolute terms over time. What the average Black K-12 student can do today is head and shoulders above what one could do 30 years ago. NAEP scores are designed to be interpretable in such a way that scores can be compared across eras. In mathematics, average scores for Black students at both the fourth and eighth-grade levels saw substantial increases over nearly three decades. The average score for Black 4th-graders rose from 188 in 1990 to 223 in 2017. A similar trend was observed for 8th-graders, whose average scores increased from 237 to 260 over the same period. Black students also have improved relative to their Black peers from the past in reading, as well, as average reading scores for Black students in the fourth grade were significantly higher in 2022 than they were in 1992, indicating a sustained positive trend over a three-decade period.

But we still obsess over the Black-white achievement gap. Why? Because these gains were not unique to Black students; White, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander students also saw their average scores improve during the same timeframe. That meant that even though they were improving in absolute terms, Black students were running in place when it comes to closing the gap with other racial groups. You can lament that this race is perverse, and I’d probably agree with you, but as long as the structure of American economic achievement is what it is, you can’t ignore these dynamics. It’s relative performance that results in college acceptance and labor market improvements, not absolute, and white kids have been learning this whole time too, so the absolute gains of Black students don’t result in sufficient relative gains. And this speaks to the point made in my three-part definition of my educational philosophy above: any new pedagogical or administrative developments that actually lead to greater learning gains are very likely to help high-performing students as well as low-performing.

Any skill that you hope to sell in a labor market, any skill at all, is not evaluated solely on a binary can do/can’t do basis. People spend hours researching which plumber to hire because different plumbers have different levels of reliability and skill; giant firms spend millions to identify and hire the best job candidates precisely because the relative differences in their abilities matter. As long as that’s true, as long as the job market is the identified vehicle for improving the economic fortunes of those struggling in our current system, then you very much do care about relative ability and relative learning. If you hope that schooling is going to create economic opportunity and thus racial equality and social justice, you’re hoping that students who have traditionally struggled will catch up with or exceed students who have traditionally excelled - and you are thus definitionally invested in relative learning, relative performance.

Indeed, one of the little ironies of this debate is that the people who are actually best equipped to focus only on absolute learning are those who understand that relative position is largely immutable - people like me. Liberate schools from the fixation on creating economic opportunity, and suddenly they can dedicate themselves to learning as learning. But as long as education is seen as valuable primarily for its dubious ability to reorder our socioeconomic hierarchy, learning for its own sake will always take a back seat.

Doesn’t the Notion of Inherent Academic Talent Imply Racist or Sexist Conclusions?

No. My argument is that individual students have an inherent or intrinsic academic potential or propensity, not that group performance differences (racial or gender or whatever) are the result of inherent or intrinsic factors. My assumption, or guess, is that such group differences are the result of environmental and social factors that are particularly hard to address because they are massively multivariate; it’s much easier to address individual influences of large effect than a very large number of influences of very small effect. (You could sit down and easily list a hundred or more environmental variables that significantly differ between white and Black children.) It’s not only possible to imagine that differences in outcomes between individual students can be intrinsic/inherent/genetic while observed group differences are environmental/social/cultural in nature, it’s quite intuitive and sensible. You might consider the analogy in this footnote.6

An early title I considered for The Cult of Smart was After the Achievement Gap, which reflects the frustration that helped inspire the book: the research record is absolutely obsessive about group differences like the racial achievement gap, but says remarkably little about what would happen after we closed that gap. Because if we take the current performance spectrum and redistribute it so that we have equal racial proportionality along that spectrum (and in so doing eliminate the racial achievement gap), we still have students who are in the bottom 50%, the bottom 25%, the bottom 10%…. We’d still have many people who are utterly unequipped for success in the meritocratic competition. And it’s hard to understand how such an outcome would be morally satisfying, even if we feel better about reducing racial inequality. This is an area of almost total myopia in elite conversations about education; because they can’t countenance the idea that different individual people have profoundly different levels of academic talent, they have no vocabulary for addressing the persistence of vast disparities even after closing every demographic gap. I do believe we’ll eventually close those gaps, precisely because I don’t think they’re the product of innate differences. But try calling that victory to the kids who are still in the 25th percentile.

On with the show.

Relative Academic Performance is Remarkably Stable Across the Educational Lifespan

Individual differences in educational achievement are highly stable across the years of compulsory schooling from primary through secondary school. Children who do well at the beginning of primary school also tend to do well at the end of compulsory education for much the same reasons - Rimfeld et al 2018

The story I’m telling is one reality has been trying to tell us for a long time. It’s just not one we’ve been willing to hear.

Consider, if you will, Project Talent, a massive longitudinal research study that was undertaken with the intention of serving as “the first scientifically planned national inventory of human talents.” Dozens of satellite studies have been developed using its data, and despite having been inaugurated 65 years ago, it remains one of the most important pieces of research into American educational outcomes in our history. The largest longitudinal education study in American history, Project Talent (initiated 1960) tested nearly half a million teenagers and tracked them for decades. Though academics and pundits rarely frame it this way for the usual political reasons, its central lesson is simple: students tend to stay where they start. Those who scored high as at first data collection were still scoring years later, and the same held for those who scored low. The rank ordering established in high school had remarkable staying power across life outcomes - college, jobs, income, even health. This is what education reformers are in denial about: school can raise or lower absolute scores somewhat, particularly very early in a given student’s academic career, but the relative distribution, the bands that children sort into early in life, hardly budge at all.

We could next look at the Coleman Report of 1966, a survey-based project of the Equality of Educational Opportunity initiative and another of the largest and most influential studies in U.S. history. It was commissioned to see if there were disparities in school resources between minority and white students. The report's most controversial and enduring finding was that differences in school funding and resources (e.g., libraries, science labs, teacher salaries) accounted for very little of the variation in student achievement. Instead, the study found that family background and the characteristics of a student's peers were the most powerful predictors of academic success. James Coleman concluded, “schools bring little influence to bear on a child’s achievement that is independent of his background and general social context.” This fits with my assumptions very cleanly: these “social context” factors are the kind of society-scale inequalities that can prompt group differences, while the individual differences that are assumed to be addressable by schools generally aren’t.

To finish our tour of giant 1960s studies, consider Project Follow Through, the largest educational experiment7 ever conducted in the United States. Running for nearly 30 years and involving more than 200,000 children, it tested almost two dozen competing models of instruction, from the most traditional to the most progressive. Its results were devastating for the reformist narrative: with vanishingly few exceptions, none of these models could alter the fundamental shape of student achievement in general terms, and none could produce meaningful distributional (that is, relative) changes.8 Students who began ahead tended to stay ahead, students who began behind stayed behind, and the rank ordering of children remained stable no matter which pedagogy they received. If billions of dollars and thirty years of experimentation couldn’t move the needle on relative achievement, there’s little reason to think the latest fad in instructional design will do so.

In more than a half-century since, this basic dynamic has been replicated again and again: the rank order of any given student, relative to peers, tends to remain remarkably stable across the entire length of a student’s academic life, and while there are individual exceptions, from the standpoint of the system the static nature of relative performance is remarkably reliable.

There is an immense amount of research that points in this direction, but much of the evidence is incidental to the intent of the authors; most educational researchers appear loathe to admit the dynamic I’m describing, out of misguided egalitarian sensitivities. Still, some quality work that directly references the stability of relative performance over time does get published. A recent meta-analysis of 363 longitudinal studies, involving over 740,000 individual participants, provides strong quantitative evidence for my argument. This comprehensive review establishes that the mean rank-order stability of school achievement is strongly and significantly correlated. This high correlation indicates that a student’s position within their peer group is remarkably consistent over time. The analysis further revealed a distinction in stability between different metrics: standardized achievement tests showed a higher long-term stability compared to teacher-assigned metrics like grades. While both measures are comparably stable in the short term, the stability of grades decreases slightly more significantly over longer intervals. This is unsurprising, as grading introduces more subjectivity and noise than test scores.

At essentially any point along a given student’s educational journey we can take their outcomes relative to peers and enjoy strong predictive ability about their performance at later stages. If you’d like to go short-term, student performance in third grade predicts student performance in fifth grade very well, as you would imagine. If you prefer long-term, academic skills assessed the summer after kindergarten offer useful predictive information about academic outcomes throughout K-12 schooling and even into college. Similarly, third-grade reading group, a very coarsely gradated predictor, provides us with reliable information about how well a student will be doing at the end of high school. The kids in the top reading group at age 8 are probably going to college. The kids in the bottom reading group probably aren’t. Likewise, a staggering disparity in long-term outcomes can be observed based on 8th-grade standardized test scores. Students who scored at an advanced level in 8th-grade reading were found to be approximately 62 times more likely to earn a four-year bachelor's degree than students with the lowest reading scores. Similarly, students with advanced math scores in 8th grade were associated with significantly higher rates of college attendance and four-year degree completion. With each downward shift in a score category, the likelihood of a student completing college sharply declined.

As students age, the stability of their relative performance tends to grow. This is a well-known phenomenon and is present in all manner of contexts. For example, consider pre-K research. (We will look at this subject in greater detail below.) Once, pre-K was thought to be a great academic leveler, as initial studies of young children showed meaningful differences. But larger-scale and more sophisticated research demonstrated that these benefits fade out over time; that is, as students age, they revert to their initially assessed relative academic rank. This tendency of encouraging pre-K effects to eventually fade out reflects the greater malleability of outcomes in earlier life and the likelihood of regress towards an individual talent level over time.9 As you move forward in the age range the correlations between past and future performance tend to grow. A 2015 study found that in reading comprehension specifically, for example, “the strength of the relation between Reading Comprehension from grade to grade tended to increase over time.” Examining six longitudinal datasets, Duncan et al 2007 found that performance in core academic skill areas tended to correlate more strongly as students aged. What’s more, follow up research found that skills tend to correlate across academic domains, as “early math skills… were as predictive of later reading achievement as were early reading skills.” Unsurprisingly, later-life academic comparisons, like high school to college and college to various forms of graduate school, are particularly robust.

The persistence of relative academic performance is especially remarkable when we consider the length of time separating various data collection events and the variety of outcomes we can predict. Standardized test scores collected at the age of thirteen are strong predictors not just of future high school and college educational performance but adult outcomes like academic career milestones and economic position, even after adjusting for family income:

Consider what it means for a test of 13 year olds to be a strong predictor of who will receive a doctoral degree. The average age for an American to receive a doctoral degree is around 31 and a half. That means that we’re talking about an average (with a large standard deviation) of eighteen and a half years between test administration and degree conferral. It’s powerfully difficult for a purely environmentalist vision of education to explain this predictive accuracy. Over the course of almost two decades, different students are going to be learning in different schools and from different teachers, having all manner of different life experiences, drawing from different educational and quasi-educational opportunities like internships and travel, developing relationships with very disparate peer groups, being influenced by the hand of fate and variability, and generally having remarkably different cognitive and academic experiences and influences. And yet their academic potential as measured at 13 years old is sufficiently powerful to serve as a strong predictor of a terminal degree almost always conferred on people in their late 20s or older. This is one of many dynamics that are easy to explain from the standpoint of innate ability and almost impossible to explain from simple environmentalism.

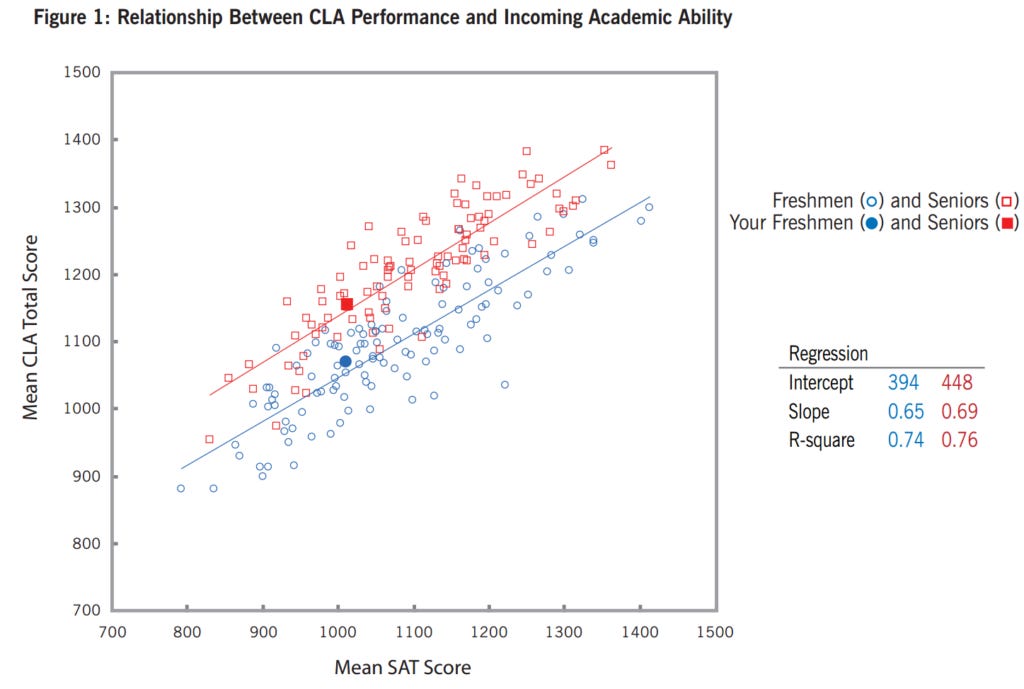

If you’re a college administrator, what’s the best predictor of how your incoming freshman class will perform as college seniors on a standardized test of college learning? Their performance on the SAT as high school seniors, of course. What else? Here’s an elegant visual to demonstrate how students can grow in absolute terms while staying in place in relative terms:

The data points here are institutional average scores on the Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA), a standardized test of college learning. Each blue circle represents the average score for a given institution’s freshman, while each red square represents the average score for a given institutions seniors, regressed on the average SAT scores for those institutions. (Data points don’t line up perfectly on a vertical axis because of attrition in the samples over time.) As we move right along the X axis, we see schools with higher and higher average incoming SAT scores for their accepted students; as we move up along the Y axis, we see schools with higher and higher average performance on the CLA. Using SAT scores this way helps to adjust for pre-entry ability, an essential practice when trying to make fair comparisons across institutions.

This all fits very elegantly with what we’ve been talking about. The distance between the blue and red regression lines represents absolute learning, how the students at the average college have improved over the course of their college careers in an absolute sense. The relationship between the variables, the tight grouping and angle of the data pattern shows that the relationship between the mean SAT score your students got near the end of high school and the mean CLA score your students got near the end of college is quite strong. Similar relationships have been observed with similar tests such as ETS’s Proficiency Profile. If your admissions process screened out weaker students coming in, your reward was stronger students going out. Obviously! Were individual student outcomes as elastic as people in the policy and politics world assume, you wouldn’t predict this kind of relationship. Students would go to different colleges and the supposedly-dominant environmental variables would overwhelm prior advantage and create very different relative performance outcomes. But that simply doesn’t happen.

If you’re an administrator at a college that’s not selective, you can take heart in the fact that even though your student body is likely on the lefthand side of the plot due to low incoming SAT scores, you can move your institutional average northwards over the course of a class’s career by producing absolute learning gains. Your students will leave knowing more than they did when they came in. But what you probably can’t do - what there’s simply no reason to believe you can do, really - is teach your students so well that they catch the student bodies of the schools on the right half of the plot. Because those students not only started out ahead, they’re learning at college too, inconveniently. There is no evidentiary basis for the conventional wisdom that schooling can change the performance of students relative to their peers, with any consistency at anything like scale - and it’s change at scale that would be required to “fix our education system.”

This essay is concerned with academic/educational outcomes as traditionally defined rather than measures of raw processing or reasoning such as IQ tests. However, these phenomena are clearly deeply interrelated, and here we have a great deal of strong evidence at very large ns. To pick one example out of many, the remarkable Scottish Mental Surveys of 1932 and 1947 and follow up research allow us to see across many decades of life. Unsurprisingly, IQ is a largely static property across large swaths of human lifespan, as can be seen in this scatterplot. As your own experience will no doubt suggest, smart people don’t often simply stop being smart, absent some sort of traumatic injury or disorder. Captured in that scatterplot above, no doubt, are instances of alcoholism, abuse, imprisonment, poverty, exposure to environmental contaminants, the development of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s and dementia…. And yet the association between IQ at 11 and IQ at 80 remains strikingly strong over lifespan. Cognitive ability remains quite stable over life until age-related decline sets in, and obviously the falling correlations associated with this decline do not suggest that cognitive ability is malleable in any constructive way.

Interestingly, students seem to understand this dynamic themselves, as they tend to be good predictors of their own future academic achievement. In data from John Hattie’s “visible learning” research, “the highest recorded influence in the study” was self-reported grades, which “simply means that students predict their [future] performance – usually accurately – [based] on their past achievement.” Reformers often deride this tendency as self-fulfilling prophecy, the Pygmalion effect, stereotype threat, the Matthew effect, or similar. But another way to think about this is that students have the best understanding of their own strengths and weaknesses and tend to assess them realistically.

Many will reply to this essay by saying that, even if I were to prove that academic talent is innate, that would be insufficient - just because something is innate does not mean that it is unchangeable. This is true, and I haven’t and wouldn’t say that educational outcomes are permanently immutable. The question is, what can we do from the perspective of the system that would work to “fix our schools,” to achieve the (remarkably vague) education-driven social outcomes politicians and policy types want? How would we close the gaps? Again, I have to stress a central practical fact: it is not sufficient for a given intervention to improve metrics for students at the bottom. To produce social and economic effects, those improvements must move students at the bottom into a better position relative to those students at the top. (Which forces us to acknowledge the uncomfortable fact that upward educational mobility for students at the bottom requires at least some degree of downward educational mobility for students at the top; relative mobility, whether in test scores or in income, is always zero sum.)10

The kind of intervention we’re looking for has to

Have a meaningful influence on academic outcomes where so many others have failed

Be reliable, replicable, and scalable to a vast degree

Cost little enough that the administration of this intervention is economically and politically feasible

Somehow apply only to the students who are struggling or any subset thereof, and not to the students who are already flourishing, or else allow for us to prevent the parents of flourishing students from accessing this intervention for their own kids, lest we merely advance the whole student population forward but preserve the current relative distribution that determines professional and monetary rewards under meritocracy.

Simple.

I quote James Heckman, a researcher who has both produced a tremendous amount of data that buttresses my perspective and yet has remained stubbornly dedicated to the dream of an educational revolution. Ten years ago he wrote

Gaps arise early and persist. Schools do little to budge these gaps even though the quality of schooling attended varies greatly across social classes…. Gaps in test scores classified by social and economic status of the family emerge at early ages, before schooling starts, and they persist. Similar gaps emerge and persist in indices of soft skills classified by social and economic status. Again, schooling does little to widen or narrow these gaps.

I would argue that, in the years since, the evidence that academic hierarchies are essentially static has only grown.

Teachers and Schools Are Not Guilty

Over the last 50 years in developed countries, evidence has accumulated that only about 10% of school achievement can be attributed to schools and teachers while the remaining 90% is due to characteristics associated with students. Teachers account for from 1% to 7% of total variance at every level of education. For students, intelligence accounts for much of the 90% of variance associated with learning gains. - Douglas K Detterman

The education reform wars of the 21st century have been consistently nasty, and it’s no wonder why: the conventional neoliberal reform story identifies bad schools and bad teachers as the fundamental problem in education. Our failing educational system - which, for the record, was never really failing11 - had to be the product of lazy, incompetent teachers and low-quality schools. Reform advocates railed against career educators and called for policies that, implicitly or explicitly, would require firing hundreds of thousands of teachers and closing hundreds of schools across the country. Alternatively, more left-leaning critics would be likely to assert that the problem lay in the lack of funding and resources for our schools. A perspective that received very little attention was the one I’m articulating here: that we should expect a normal distribution of student ability such that there will always be a predictable and unfixable portion of students who struggle thanks to their lack of prerequisite abilities, and our inability to close performance gaps at the school side is not evidence of untalented or lazy teachers but of the simple fact that those gaps are the product of forces that teachers can’t possible change.

The easiest way to demonstrate why teachers and schools were unfairly targeted is to look at a wealth of research demonstrating that genuinely random placement into different schools (and of different perceived quality) has no effect on student outcomes. This must be underlined: a large body of research shows that randomly placing students into various schools, often dramatically different schools, has no impact on student outcomes. This flies directly in the face of the naive assumption that student outcomes are simplistically a product of school or teacher inputs and, as I have argued, contributes to a deeper understanding that in the way typically understood, school quality does not exist.12

What do some of the relevant studies show? Let’s review. Winning a lottery to attend a supposedly better school in Chicago makes no difference for educational outcomes. In New York? Makes no difference. What determines college completion rates, high school quality? No, that makes no difference; what matters is “pre-entry ability.” How about private vs. public schools? Corrected for underlying demographic differences, it makes no difference. (Private school voucher programs have tended to yield disastrous research results.) Parents in many cities are obsessive about getting their kids into competitive exam high schools, but when you adjust for differences in ability, attending them makes no difference.13 The kids who just missed the cut score and the kids who just beat it have very similar underlying ability and so it should not surprise us in the least that they have very similar outcomes, despite going to very different schools. Highly sought-after government schools in Kenya make no difference. Winning the lottery to choose your middle school in China? Makes no difference. I will address the highly-touted charter school advantage in its own section below.

This study, helpfully titled “Going to a Better School,” finds that moving to a school perceived to be substantially better yields very small test-score gains - like, around 0.05 SD, so zero practical significance. Similarly, this study finds that once you account for selection effects, moving to a selective school has no difference for student outcomes. That is the most essential element of all of this, understanding the role of selection effects, which I have long argued are the most powerful force shaping perceptions of educational quality in our culture. Parents look at the local private school, see lots of high-performing students, and conclude that the private school is superior at educating. But of course private schools systematically exclude large swaths of students. All private schools exclude students whose families cannot afford to pay, and family income is broadly associated with academic performance14; many or most private schools also have educational admissions standards that further ensure that they are systematically excluding the hardest students to educate. Of course they then graduate academically impressive students. As I’ve said before, this is akin to having a height minimum for your school and bragging about how tall you’ve made them.

You can see the lack of control teachers have over student outcomes in the repeated failure of merit pay programs and the associated “value added models” schools and districts have attempted to use to assess teacher quality. Such schemes have repeatedly failed to demonstrate durable improvements in student learning, and in many cases suffer from methodological fragility. Critics argue that VAMs attempt the impossible - extracting isolated teacher contributions from a complex web of factors like family background, attendance, peer effects, and non-instructional school resources - with available data typically limited to proxies like free-lunch eligibility or special-education status, leading to arbitrary and unstable results. RAND analysts have shown that standard errors in VAM estimates are large, meaning that teachers rated as “highly effective” may in truth be average, or vice versa. VAMs have in fact been subject to many damning critiques, such as in the paper that demonstrated that “the standard deviation of teacher effects on height is nearly as large as that for math and reading achievement, raising obvious questions about validity.”

The merit pay systems that VAMs are meant to power, meanwhile, have consistently failed to produce any learning gains. A rigorous Nashville performance-pay experiment found no discernible improvement in student achievement as a result of financial incentives for teachers, while a comprehensive meta-analysis pegs the average impact at a minimal 0.043 standard deviations, a grain-of-sand style effect, which diminishes further when implementation duration and subject matter vary. The broader historical record is even more damning: as education scholars point out, merit-pay schemes have been tried, failed, and resurfaced repeatedly over decades with no lasting academic benefits. VAM-based teacher assessments and merit pay systems risk misclassification, demotivation, and distraction from meaningful improvement, without delivering measurable or lasting boost to student learning, all at the cost of teacher trust and buy-in.

Meanwhile, a beloved argument for progressives doesn’t appear to have much empirical basis either, the claim that school outputs are simplistically a function of school funding. Traditionally, regressing school funding on schedule performance on the country level has shown a clear threshold point beyond which more funding doesn’t matter - once you hit a certain minimum level of funding, there’s simply no relationship. Lately there have been a number of studies that attempt to establish this connection despite the fact that higher-funded schools and districts do not summatively do better in quantitative metrics. Again and again and again, we find that there is no clear relationship between school funding and student performance - higher-funded countries, states, districts, and schools do not consistently perform better than lower-funded. But researchers keep coming up with these abstruse and complicated models that suggest that money does matter, which coincidentally is exactly what the people who do the hiring and funding in academia want to hear. I’m afraid that I just have to keep pointing out the obvious: the United Kingdom spends far more per-pupil than Russia but does worse, Utah spends the least per-pupil while New York spends the second-most but barely does any better, in state after state there’s no relationship between the best-funded districts and the best-performing districts…. Read all about it.

For the record: poorer and Blacker American schools receive significantly better per-pupil funding than richer and whiter schools. This is both perfectly predictable from the policy context (we’ve been throwing money at the racial achievement gap for about a half-century) and appropriate, if you believe in spending more where there’s the most social need. (That is, you can support spending the most money on the schools with the most material depravation without believing that money will close gaps.) But people react very unhappily to being told that the most deprived students receive the most school funding, no matter what the facts say. Regardless, if throwing money at our educational problems solved those educational problems, they would have been solved a long time ago. Here the reformers are correct: we can’t spend our way out of this.

All of this confirms anecdotal experiences. Did kids you know go from failures to whiz kids when they moved to a different state, a drastic change in environment? Did you, yourself, dramatically change your position relative to the kids around you over the course of K-12 education? Does sending a kid to private school solve all of that kid’s educational problems? Do Montessori principles ensure that even severely struggling children can succeed? Are students constantly jumping around in the student rankings as they cycle through different teachers from grade to grade, as you’d expect from a purely environmentalist perspective? No, of course not. Because they’re the same kids. Why doesn’t this simple wisdom penetrate policy and politics?

Teacher quality perhaps exists but likely exerts far less influence than generally believed. There is no such entity as “school quality.” The concept is an illusion. There is the underlying ability of the students in a school who produce metrics that we then pretend say something of meaning about the school itself. That’s it. Put together with robust behavioral-genetic evidence that individual differences in cognitive ability and achievement are substantially heritable and increasingly stable with age, the most plausible reading of the literature is this: schools can raise absolute skill levels for some students and improve life chances in specific ways, but they are not a panacea for deep, early-rooted inequality that emerges from structural social inequalities and from differences in innate ability.

The Charter School Con

There’s no “solution” to our supposed educational crisis that’s been sold more aggressively than charter schools and the broader “school choice” movement. Unfortunately, outsized claims about a supposed generic charter school advantage have consistently crashed against the rocks of reality, despite a relentless effort by our media and much of academia to support this narrative.

Large-scale, national studies on charter school performance have generated top-line results that appear to favor the charter sector. A 2023 study by the Stanford-based Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO), which drew on data from the 2015–2019 school years, found that the typical charter school student had academic gains that outpaced their peers in traditional public schools (TPS). On average, these students gained an additional 16 days of learning in reading and six days in math over a year's time. This finding has been widely cited as evidence of the sector's positive impact.

However, a closer look at the data reveals that this positive national average is a statistical abstraction that obscures a fundamental truth about the charter sector: its extreme heterogeneity. The national aggregate is heavily influenced by a non-representative subset of schools, particularly those located in urban areas and those affiliated with Charter Management Organizations (CMOs). For instance, the CREDO study found that urban charter students demonstrated far more significant gains, with an additional 29 days of growth in reading and 28 days in math per year. (Put a pin in that.) This finding is consistent with a National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper, which noted that while charters perform at about the same level as their district counterparts on average, those in urban areas appeared to consistently boost test scores, especially for Black, Latinx, and low-income students. Conversely, other parts of the sector show weaker performance. The CREDO study found that rural charter students had the equivalent of 10 days less growth in math, and virtual charter schools showed large negative effects. (Like, disastrously bad effects.)

Then there’s this whole “days of learning” metrics, which is a classic example of fine-tuning an output variable to make outcomes seem better than they are. While the top-line results from studies like CREDO's have drawn significant media attention and led to claims of “unequivocal” success, a critical examination of the methods and the magnitude of the gains challenges this perception. The CREDO study's days of learning metric is controversial among researchers and difficult to interpret. When converted to a more common and understandable metric, the findings show that attending a charter school for a single year would raise the average student’s math score from the 50th percentile to the 50.4th percentile and their reading score to the 51st percentile. The small size of these gains is often obscured by the more dramatic days of learning metric.

(CREDO, for the record, is a pro-charter shop that’s treated as some neutral party in our media; CREDO researchers are usually charter true believers who arrive at the project with a preexisting bias towards the charter model.)

What’s more, the methodologies used to compare charter and traditional public school students come with significant limitations. CREDO's approach, which matches charter students with “virtual twins” from nearby district schools, is a serious attempt to create a comparable dataset. However, this strategy does not guarantee a truly apples-to-apples comparison. The basic problem is that these methods cannot fully account for critical, unobserved factors that differentiate students who attend charter schools from those who do not, such as inherent motivation, parental engagement, and family background. There are massive selection bias issues with charter schools that result in dramatically different student populations in traditional public schools and charter schools.

To pick a salient example that has long haunted this debate, because families self-select into the charter school system, a true comparison group that is identical in every respect remains elusive. That is to say, simply the fact that parents might opt into the lottery system for charter schools can bias analysis in favor of charters. Hoxby & Murarka (2009), for example, note that lottery-based evaluations are the “gold standard” only within the applicant pool - that is, the group of families motivated enough to enter the lottery - not the broader population of students. A RAND analysis from the same year argued similarly. This inherent self-selection bias means that some of the observed differences in academic outcomes may be due to pre-existing student characteristics rather than the school environment itself.

Charter supporters insist that “demographic matching” ensures that research compares apples to apples. We might note, first, that while sufficient similarity is often asserted when it comes to high-profile research scenarios, many many charter schools in fact do not have anything like the same demographics as their geographical peer public schools do. We know, for example, that New Jersey charter schools enroll significantly fewer special ed students and that the students they do serve have less damaging disabilities. (The famous New Jersey CREDO study has numerous methodological issues, for the record.) The highly-regarded MaST Community Charter School of Philadelphia has 41% low-income enrollment; the city’s public schools have 91% low-income enrollment. In one Georgia town the local charter school is 73% white, while the public schools in the district are 12% white. What could be the source of these enormous disparities if not deliberate bad behavior? But again, charter advocates love to point to research that demographically matches students across charter and traditional public contexts - that is, they insist that the student body populations are equivalent by showing that they have similar racial compositions, gender compositions, familial income compositions, etc. But as this essay should make plain, demographic matching is insufficient. What you would need, if you wanted to really prove equivalent teaching and learning conditions, is academic matching, students of equal talent and pre-entry ability. Unfortunately, because ed researchers don’t like to admit that different students have profoundly different levels of academic talent, this obvious problem is ignored.

Furthermore, charter schools operated by CMOs, while comprising only a quarter of the schools in the CREDO study's national dataset, served 37% of students and were responsible for a disproportionate share of the observed learning gains. This suggests that the positive average performance is driven by a small number of high-performing networks, while a significant number of charters - particularly stand-alone and rural schools - show similar or even worse results than their public school counterparts. The debate over the value of “charter schools” as a monolithic entity is thus unproductive, as the evidence shows that success is concentrated in specific contexts under certain conditions… and that’s if we trust the CMO results, which we shouldn’t.

Why not? Because the conduct of these schools demonstrates that they don’t trust their own supposedly superior instruction. In 2016 at least 253 charter schools in California were found to be illegally manipulating their student bodies to exclude those who were least likely to succeed and enroll those who were most. Similarly, a 2013 investigation by Reuters reported that

across the United States, charters aggressively screen student applicants, assessing their academic records, parental support, disciplinary history, motivation, special needs and even their citizenship, sometimes in violation of state and federal law.

There are many individual cases of charter school admissions misconduct that you can investigate, along with other types of fraud. In fact the charter system is so rife with graft and mismanagement that it was reported in 2019 that the federal Department of Education has wasted $1 billion on various shady or incompetent charter schools, including many demonstrable cases of charter schools deliberately manipulating their student bodies to exclude undesirable students, in exactly the way I’m criticizing.

This is all to say nothing of grey-area student body manipulation practices, such as through charter school applications themselves; these are efforts to massage student bodies that stop short of out-and-out fraud but which still amount to putting a thumb on the scale in terms of who gets in and who doesn’t. A classic way to manipulate which kinds of students end up enrolling is by enforcing application requirements that are so onerous they strain credulity. Consider this mountain applicants had to climb to apply to a Los Angeles area middle school:

The “Getting to Know You” sections require would-be students to write five short essays covering two pages (“use complete sentences”) on a variety of topics (“Tell us about your family”). Then there’s a third page calling for short responses on an additional six issues (“The qualities and strengths that I will bring to school are… .”).

Wait, wait. We’re just getting started. The parents have to write seven little essays of their own and then fill out the child’s medical history, including medications (an intrusive request that some critics say violates federal privacy law) — and remember, this isn’t for an accepted student to attend, but for a student to apply in the first place. It’s capped by the would-be student’s minimum three-page autobiography, typed, double spaced and “well constructed with varied structure.”

Beyond this kind of direct, unambiguous admissions skullduggery, the simple reality is that charter school results are utterly dependent on the integrity of their lotteries, and we have no reason to trust that integrity. We simply do not have good public information on the real-world conditions of charter school lotteries. They are hugely important for the children who are being sorted and for the research that informs our future policy, but I can tell you from researching my book that getting solid information that goes beyond parroted lines about the official process is quite difficult. Repeated efforts to research accountability mechanisms have mostly turned up a lot of blanks. What’s really going on in these vitally-important events? I don’t know. You don’t know. Nobody knows.

Not only is there a lack of consistency between different states in charter school lottery practices, from what I’ve gathered there is also a lack of consistency within some states and even within some municipalities. There’s also a profound lack of transparency in many of these lotteries; they occur behind closed doors, often undertaken by charter employees who operate under less regulation than their public school peers. That really is the worst of all - in many cases the schools themselves are handling key parts of the lottery process or the entirety of the lottery process. They have direct financial incentives to cheat, and yet in many cases they have multiple opportunities to influence the results. When you give people incentives to break the rules and you trust them with enforcing those rules themselves, they’ll break them. (Certainly including public school educators.) The honor system is not a check on cheating.

There’s also the question of backfill. Backfilling refers to what you do when students drop out of the school - do you fill in those seats, or don’t you? If you don’t fill them in, you’re going to look better by the numbers. The students who drop out of K-12 schools are the more transient by definition and the more transient students tend to be the more academically marginal. Public schools generally have no choice but to backfill given their enrollment policies. Charter schools often get to choose and, unsurprisingly, frequently do choose not to replace their poorly-performing dropouts with new enrollees who might prove to perform poorly themselves. This has consequences in terms of their quantitative metrics.

Media darling Success Academy charters is an attrition factory in part because of strict backfilling practices for grades past fourth (previously third). The first incoming Success Academy kindergarten class had 83 students. By the time those kids got to their senior year of high school there were 17 left. Then Success Academy bragged about what a high percentage of those remaining students got into college, with no word on the vast majority who were no longer in the system! This success-through-attrition should not surprise us, coming from the home of the “Got to Go” list. (When Eva Moskowitz is asked about the disparity between the student body that starts and the student body that finishes at Success Academy, she dissembles.) The founder of the celebrated Boys Latin charter school in Philadelphia just straight up said that backfill policy is how they get the best students. In general the sheer mass of students who start at charters but don’t finish is a scandal. KIPP schools are similarly ballyhooed, yet 40% of Black students leave before graduation. In the past Washington DC charter schools have had expulsion rates more than 72 times that of their public school counterparts. Are you noticing a pattern?

The most common and widely cited form of getting rid of undesirable students without influencing performance metrics is the practice of “counseling out,” a process by which charter school administrators advise the families of students who do not meet the school's standards to leave and enroll their child in another school. This is particularly common for students with disabilities or behavioral issues, as their needs can be expensive to meet and their test scores may lower the school's overall performance. Unlike traditional public schools, which are legally mandated to serve all students with disabilities, charter schools can use this unofficial policy to strategically shape their student population. This practice of counseling out is often so subtle that the schools can deny its existence, as students are rarely officially expelled but are instead pushed out through persistent pressure or threats of punishment.

Here’s the question: if the charter school advantage is real, why would these schools behave this way? Why would they commit admissions fraud? Why would they “counsel out” difficult-to-educate kids? Why would they allow backfill to improve their numbers via attrition? Why would they have “got to go” lists? If charter school magic is really magic, why would so many schools be caught engaging in so much explicit student body fraud, and so many more engage in dubious practices that have the effect of leaving them with the most talented students? Well, it makes perfect sense - if there is no charter school magic, if the ability to chase off low-performing students just is the charter school advantage.

Nothing “Works”

Many critics of my observations here assert that the static nature of student performance is no surprise because most students maintain static educational environments over the course of life; impoverished students in failing school districts continue to be impoverished and continue to face the same social challenges they already have, privileged students enjoy similarly static environments, therefore it’s no surprise that students mostly stay in the same place. The problem with this reasoning is that we’ve made massive efforts to change student conditions in schools and classrooms, and they have almost universally resulted in minimal differences in quantitative success metrics.

Despite decades of pedagogical research and development, real-world evidence consistently shows that most academic interventions deliver only modest, inconsistent, or negligible gains. The null hypothesis haunts education research; everywhere we look, we find dogs that didn’t bark. We try all sorts of things, and one by one, they fail to produce meaningful academic differences in research.

For example, many claims have been made about mindset and the power of positive thinking in education, but such mindset interventions are found to have tiny effects, fail to replicate, or both. “Grit,” an operationalization of concepts like stick-to-itiveness and resilience, was briefly a sensation among the TED Talk set, but further investigations found that the effect sizes associated with the concept were very small and vastly less meaningful than differences in raw intelligence. The concept is also essentially a rebranding of the well-studied psychology concept of conscientiousness, one of the “Big Five” personality factors. Grit studies and similar research are also hampered by the fact that our assessments of student grit are usually driven by student self-reporting, which introduces a tremendous amount of noise. Growth mindset studies have similar issues with self-reporting and reliability, and a major review of growth mindset studies, spanning hundreds of cases, finds the effects weak. There’s also persistent questions of whether grit or growth mindset are really more malleable than intelligence; if we can’t change our grit or mindset, there’s no policy benefit.

Educational technology is a notorious graveyard of initiatives that were launched to immense fanfare and then crashed and burned. There’s no better place to start than the hideously expensive LA school district boondoggle, where the Los Angeles public school system spent $1.2 billion on new iPads for their students while the buildings crumbled. The program was a disaster and led to ethics investigations into local government agencies and prompted the resignation of the superintendent of schools. Randomized controlled trials demonstrate that neither giving random American students desktop PCs nor giving random developing world students laptops has any measurable impact on student learning. In fact, long-term follow ups on the One Laptop per Child program in Peru found that, in addition to not providing any educational gains or cognitive skills, the students who received the laptops actually had worse outcomes in terms of completing school on time! Meanwhile, much ballyhooed “learning analytics dashboards” have not produced any tangible or consistent impact on student learning. Despite marketing claims, digital textbooks do not provide any learning advantage compared to paper. Some research suggests that digital text leads to slower reading and worse comprehension compared to paper.

There are all manner of factors that are believed (hoped) to have a meaningful impact on student performance that don’t, too many to list. Does playing high school sports help students learn? No. Giving students free lunches? No, though you absolutely should still give kids free lunches. Playing chess? No. Playing a musical instrument? No. Speaking a second language? No. Neither participating in extracurricular activities in general nor enjoying a sense of belonging from this participation is associated with any superior learning outcomes.

Meanwhile constantly cited explanatory mechanisms that are not primarily policy or pedagogy-driven, like class size, aren’t really explanatory at all. Calls for smaller class sizes are ubiquitous because they’re one of the few interventions endorsed by both neoliberal ed reformers and the teacher unions who are their enemies. But while quantitative effects of class size have been a research obsession for at least 40 years, there’s no real consensus on what exactly works, for which students, in which contexts. Claims of a small class size advantage routinely carry extensive lists of provisos, such as saying that it’s necessary for physical classroom space to not shrink along with number of students, the kind of requirement that makes implementing these efforts at scale a policy nightmare. And I would argue the research is discouraging anyway.