We’ve got five days left in 2022, and our RAINN fundraiser is still about $1,000 short of our goal. Let’s get past the finish line!

So, there’s this from Matt Yglesias.

There’s a couple different ways to read this. I take it that Yglesias means to say that people who have technical skill in the visual arts are uninterested in producing the kind of visual art that most people like. I’m not sure that Yglesias is right on the merits - millions of people go to art museums every year, and the modern/contemporary wings tend to be among the most popular. (Also, plenty of critically celebrated novels sell very well; Hanya Yanagihara’s exercise in misery A Little Life sold in the seven figures.) Yglesias is pretty neutral here, but certainly this is playing in the realm of straightforward reverse snobbery - you create a hierarchy of taste just like regular snobs do, but you do so by inverting that hierarchy. As the title of this post alludes to, this has been a common tactic for well over a century. The ascendance of non-representational art (often referred to as abstract art) was already well on its way in 1922, and yet we still have people like Yglesias here who have had their jimmies rustled by the fact that not everyone wants all art to look like pretty pictures of rolling green fields. Thus, the imagined caricature of an art world that’s filled with elitists who don’t have the sense to like paintings of children playing at the beach like everybody else.

You also sometimes hear suggestions that those who moved towards non-representational art did so because they lacked the technical skill to create representational art. That, at least, is simply wrong. Art history shows us that many of the most celebrated abstract artists were perfectly capable of creating traditionally representational works of art, and used those skills when it suited them. The interesting question is why they often didn’t.

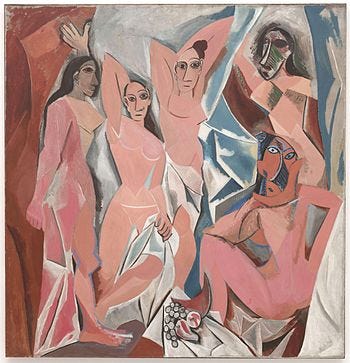

Pablo Picasso was probably the quintessential modern artist. His cubist period helped usher in the world of abstraction that so many associate with the first half of the 20th century. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, shown here, scandalized the art world, expanding the definition of what visual arts were and could do. Picasso’s willingness to bend perspective and to visually complicate faces and figures helped make his reputation. Yet here’s an early painting from Pablo Picasso.

Of course, Picasso was a famously virtuosic artist who was preternaturally skilled in seemingly every avenue of the arts that he tried. Clearly, he wasn’t lacking for technical ability; instead, it seems that at some point in his life as an artist strictly representational visual art ceased to achieve what he felt he needed to achieve. You might also fairly point out that, as abstracted as his work frequently was, Picasso rarely produced work that was purely abstract in the sense we might associate with someone like Mark Rothko.

Rothko has always attracted a lot of derisive reactions - his work is visually simple and often attracts the “my kid could paint that” cliche.1 The response to such an attitude is that the purpose of art is not always to impress but rather to invoke a feeling or mood. Besides, even Rothko was not totally averse to representation. Here's his "Underground Fantasy" from 1940.

I’m not sure if this is sufficiently skilled draftsmanship to satisfy those who insist that famous art demonstrate a narrow vision of technical proficiency, but it shows that even one of the most famous abstract expressionists was perfectly willing to play with more traditional forms when doing so served the art. (I am quite confident that Rothko was uninterested in proving that he could paint “realistically.”)

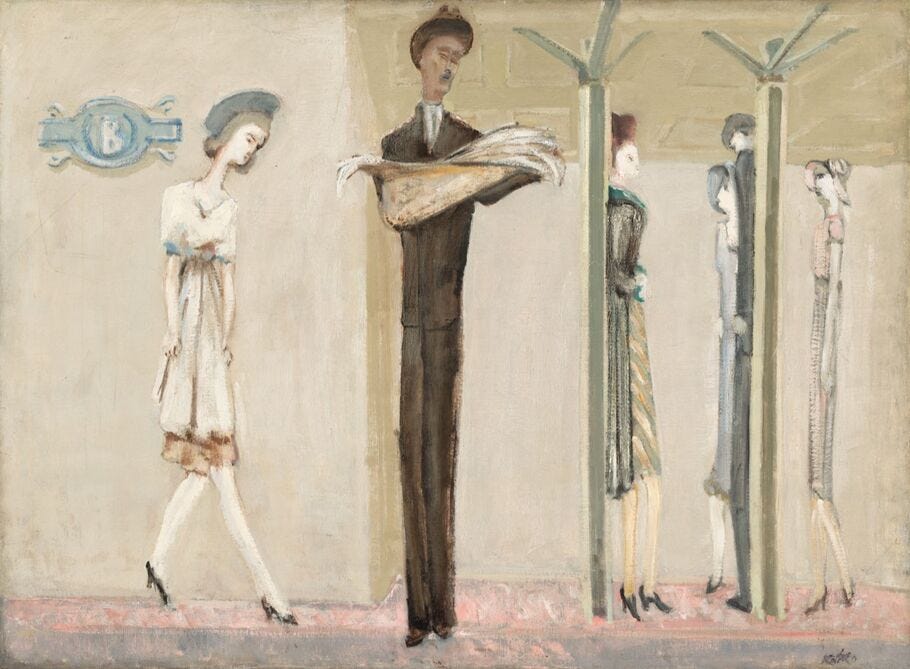

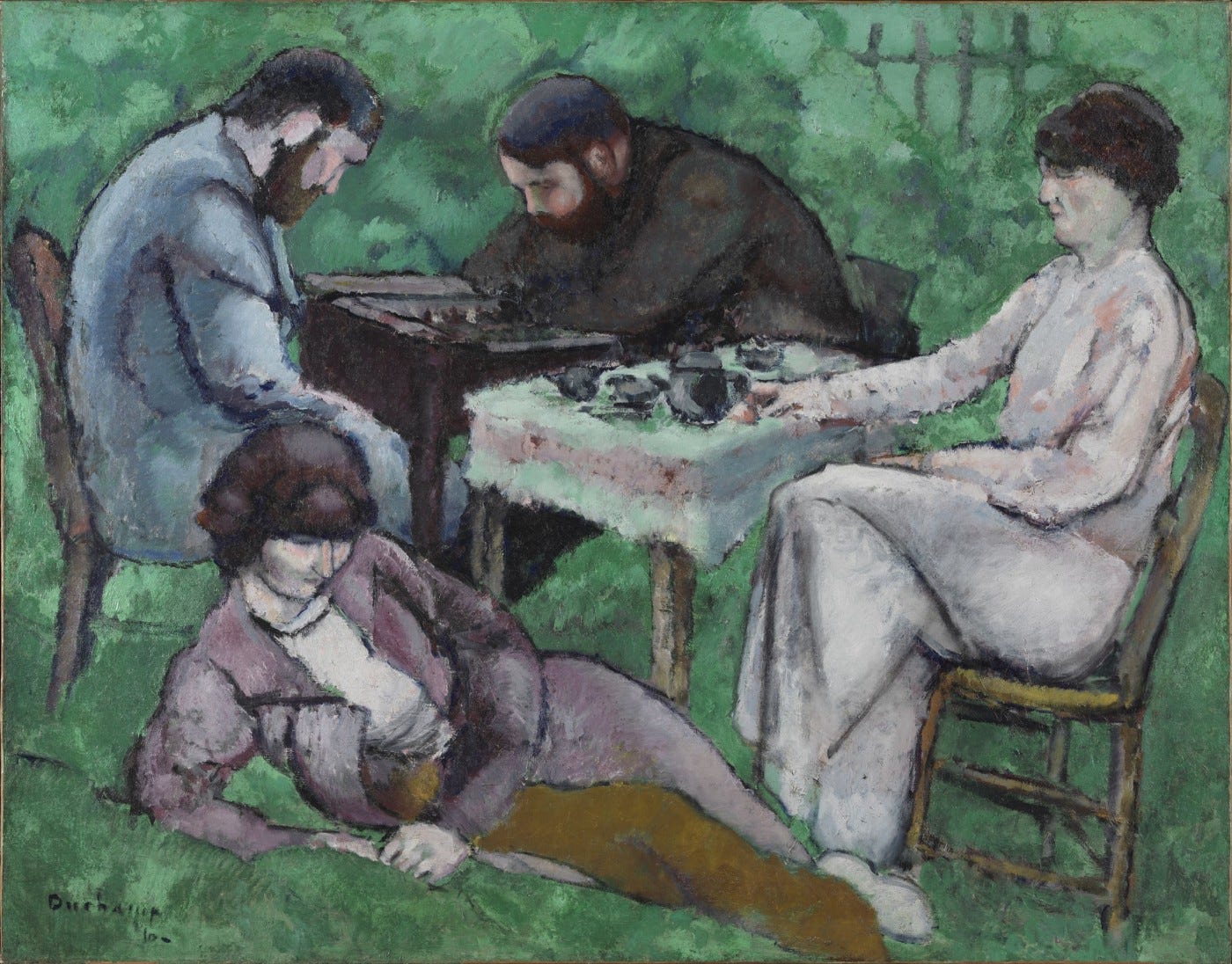

Here’s Marcel Duchamp, a famously cerebral artist who hung a urinal on the wall and called it art, with a representational painting, somewhat abstracted but hopefully good enough to rate alongside Thomas Kincade, Painter of Light.

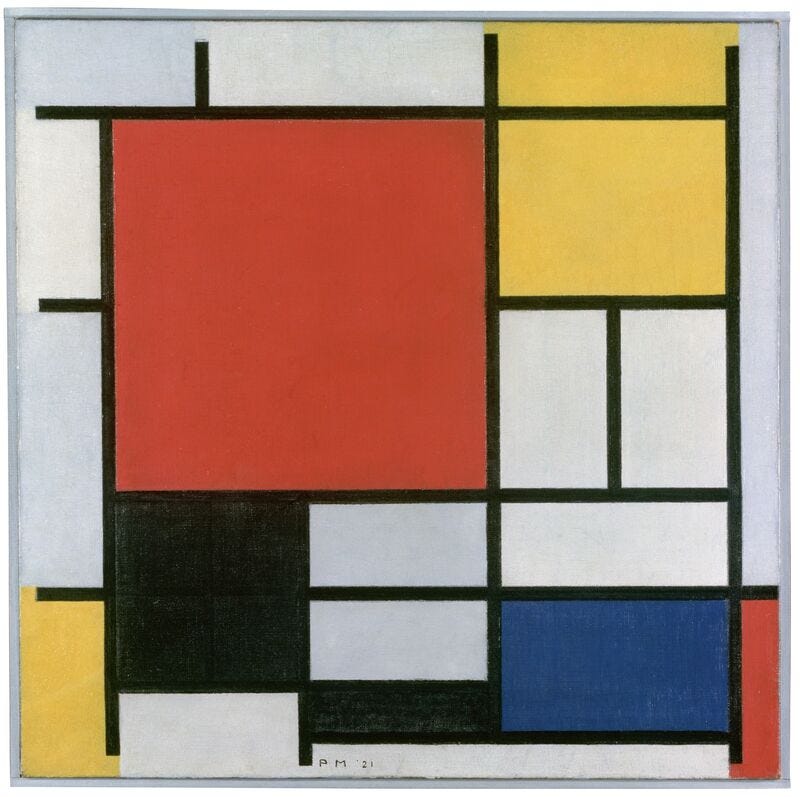

Or better yet, take Piet Mondrian. Mondrian was a consummate modernist; few painters thought more about what their work meant in terms of the definition of art and art’s purpose. He’s best known for this kind of painting:

But once upon a time, he made work that was less abstracted, such as his many depictions of trees.

It’s been argued before that you can see Mondrian’s work becoming more abstract as his career progressed. But for the record here’s a drawing of his that could probably get a good grade in an Into to Illustration course.

What’s my point here? In part, I would like you to consider whether or not there was a good reason that so many of the most talented artists in the world moved towards abstraction in the high modern period of the early 20th century. If they could draw nice pretty trees and nice pretty people, why did they choose not to? Why did Mondrian go from realistic trees to abstracted trees to pure abstraction? Here’s a well-worn and simplistic reason: the crisis of representation happened. The crisis of representation arose from advances in photography that made traditional types of art like portraiture and landscape seem superfluous. With cameras becoming cheap and ubiquitous, why spend endless hours on achieving photorealistic effects in visual arts, given that photographs would always be more true to life? Traditional draftsmanship seemed suddenly obsolete. Besides, centuries of work in representational art had already been accomplished; there was little left to do in that domain. So many artists turned inward, hoping to express not what they saw but what they felt, to capture their own emotional inner lives. When challenged by a critic who asked why he did not paint subjects from nature, Jackson Pollock said “I am nature.”

Of course, culture trudges along, and over time the abstract work that had once scandalized the art world started to become tired itself. Art went in all kinds of directions, such as performance art, or into less traditional materials, as in my beloved “A Portrait of Ross.” Some artists, such as Chuck Close, developed enviable critical reputations while working in the kinds of traditional representation that Yglesias suggests is “low status.” Anything goes, but also art arises from its own constraints. Representation and abstraction both stand as tools in the toolbox for contemporary artists, who need as many different modes and mediums as possible, given that every young artist works in the shadow of a longer and longer history of art.

Yglesias sees the rise of AI art as an opportunity for those who want supposedly low-status pretty pictures. I wonder if he’s considered the other side of the coin: the better that AI gets at creating artwork that perfectly represents visual reality, the more valuable art that instead fixates on the depiction of human interiority will become. AI art simply replicates the crisis of representation - the value of being able to paint beautiful representations of reality falls as a computer can ape those skills through machine learning. But this leaves art that foregrounds the artist’s emotions even more valuable. Were I to look out at the kind of art that these AIs create and decide where I could fill a niche, I would look at something exactly like abstract expressionism. MidJourney has no human emotions to share. Unlike Jackson Pollock, Dall-E is not nature.

As for the broader sentiment of those tweets… as I suggested, Yglesias is playing it pretty close to the vest here. I can’t say he’s explicitly expressing a particular disdain for the kind of art that Thomas Kincade didn’t make. But it’s not hard to detect resentment towards the pointy-headed “real art people” who reward work that’s something other than sun-dappled cottages in the mountain snow. To which I can only say, really? In 2022? We're still bitching about non-representational art in the 21st century? That line of complaint was tired literally 100 years ago. Yglesias is a Dalton-and-Harvard-educated scion of a well-to-do NYC family with a successful novelist and screenwriter for a father. And yet even he appears consumed by the most powerful force in American culture, the fear that somewhere, someone is looking down their nose at you.

But perhaps the endless ascension of “poptimism,” the seemingly endless period of total artistic populism we’re living in now, such resentment is actually good for abstraction, artistic difficulty, and experimentation. Years ago I got into an argument online with one of those shrieking poptimists for whom no amount of respect towards Taylor Swift will ever be enough. She was mocking me for using the term “avant-garde.” And what I tried to make her understand, unsuccessfully, was that her mockery of the idea was precisely what the avant-garde needs most. This is the Chinese finger trap our artistic populist overlords can’t get out of: the more they disdain the idea of an artistic vanguard that stretches the boundaries of what is possible in art, the more that spirit of experimentalism is reinvigorated. Challenging art needs to challenge, and in our current pop culture landscape where superheroes and bubblegum pop rule, the highbrow offends again. It may offend in a different way, but it still offends. And in art, offense is the lifeblood of the new. That some people still see a work of abstract art and get cranky about the snobs who champion it tells us that art isn’t dead.

No he couldn’t

No one cares

This isn’t Olympic diving, you don’t get points for degree of difficulty

Fuck your kid

My personal cutoff point is that I have no background in art whatsoever, so if a weird painting generates rave reviews but looks stupid af to me, that means it was made for an audience I’m not a part of. Which is fine- YA adult novels and Japanese comics and treatises on Cambodian architecture by and large fail to interest me because I’m not the target audience.

But I do kind of object to the idea that I’M the one who was caught lacking. If Piet Mondrian paints a lot of squares and lines in primary colors intending to provoke a feeling, and the only feeling that is provoked in me is “why am I bothering with this”, then I would assign the blame for the failure to connect on egalitarian lines- me for not being art-aware and him for being weird and meta.

But every so often, some piece of art seeps through the filter and I could stare at it for hours, remember it for years. My personal indifference to art that I don’t “get” is pierced through and the feelings flow.

I saw this mosaic (http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/files/2016/04/gm_00766201_800x800-1.jpg?x45884) at the Getty Villa Roman art exhibition in LA and it haunted me for years. I couldn’t remember a goddamn thing about the little label on it- all I could remember were the boxers. One standing tall and proud, the other drifting off to one side gushing blood from the head. A bull was in the background- why? No idea. Maybe it was a metaphor for stubbornness in the ring. The effect of the mosaic was hypnotic, like an early form of pointalism where the individual stones implied so much more shape and movement and detail than they actually gave. The winner showed no exhaustion, but strutted away chest out. The loser had all his weight on his right foot, implying a plodding gait as his head leaked blood. The bull was upset at something, God alone knows what.

Finally I lost my patience and google searched for it years later with the description “two Roman boxers mosaic bleeding bull” and finally got the context. It was piece of fanart, basically. There was a scene from Virgil’s Aeneid where two boxers- a young, fierce up and comer from Troy and a champion from Sicily who was maybe losing his touch as he aged- go at it in the old timey Olympics. The older champion is expected to go down, but instead fights furiously and bashes the living daylights out of the youngin’ so hard that the refs stop the fight to prevent the Sicilian from accidentally murdering the Trojan. The champ wins again and is awarded the prize bull, which he piously sacrifices to the gods by PUNCHING A FUCKING HOLE IN THE BULL’S SKULL.

The art captures the moment where the champion struts off, coming down from the adrenaline high of the fight, his opponent still staggered and bloodied, and the bull dying in the background.

I don’t think it was a coincidence that the boxers’ mosaic breached my defenses while abstract artists mostly don’t. Even with context, I can’t bring myself to give a fuck about shapes; even without context, rocks embedded onto the floor haunted my dreams. That’s because Mondrian was painting for himself and for his fellow artists, who had their own meta thing going on that I was not a part of; the artist who crafted the mosaic in the ancient Roman Empire was doing it for normal people to go “oh shit! I love that story” when they walked into the villa.

You admit that you may be stretching, but it seems to me that you're projecting a resentment into Yglesias's tweets that is uncharitable at best. I see far more "jimmies rustled" in the response than in the tweets.