It’s Book Week!

Here is the winner of the 2023 Book Review Contest! Congratulations again to Alicia Kenworthy, who’s newsletter you can find here. Sorry for the delay but when I realized I was going to do a Book Week I realized I wanted to hold off sharing this until then. Below is Alicia’s review, along with a little collection of related audio clips that she’s gathered for a potential future podcast project. I will coordinate with the two runners up about posting their entries to the website next week. Also, I’m at the Tucson Festival of Books this weekend. Say hi.

Like many women who look like me, I’ve lived most of my life untouched by America’s criminal justice system; it wasn’t until a close friend found himself “locked up” circa 2019 that I became intimately acquainted with the realities of incarceration. I rearranged my schedule to take his GlobalTelLink calls in 15-minute increments at $1.20 a pop and eagerly awaited his handwritten letters in my mailbox. Every Thursday, I placed a handful of quarters in a Ziploc plastic bag and made my way to the jail for what quickly became a familiar routine — open your mouth, take off your shoes, show the bottom of your feet, shake out your bra.

It didn’t take long for me to admit what I felt for my friend verged on something more than platonic. Under the glare of fluorescent lighting and the watchful eye of correctional officers, our relationship evolved into an all-consuming romance — this, despite a nagging question I could never quite shake:

What drives an otherwise sane woman to love a man behind bars?

Love in the Time of Incarceration: Five Stories of Dating, Sex, and Marriages in America’s Prisons by Elizabeth Greenwood is an attempt to answer that question. Is every woman who falls in love with an inmate as damaged as Dr. Phil might have us believe? Or might we learn something from couples who “press against the confines of preconceived notions” about what a relationship should be?

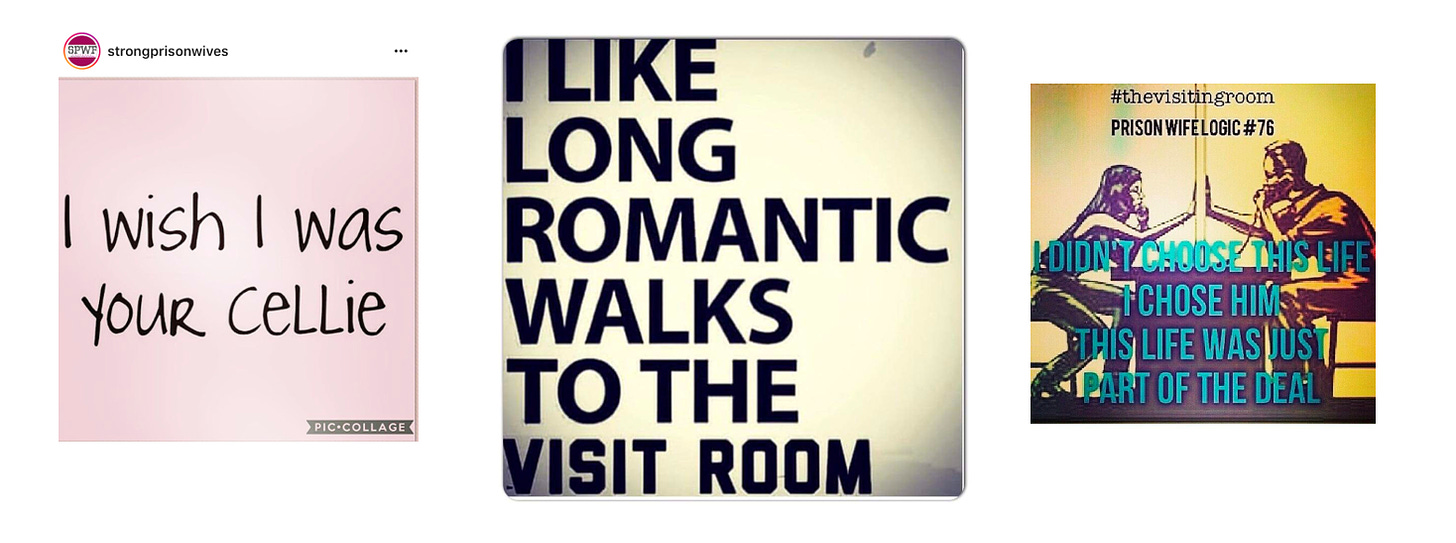

I discovered the subculture of “prison wives” not long after my own romance became official, somewhere down an internet rabbit hole of prison-related support and advocacy resources online. Online communities for women with incarcerated loved ones, many of which boast memberships numbers well into the thousands, are a unique byproduct of the country within a country that is America’s prison-industrial complex. The virtual sisterhoods - comprised of women from all different socioeconomic backgrounds and walks of life, united by less-than-ideal circumstances and the appreciation of a good meme - are often a lifeline for women experiencing the vicarious incarceration of someone they love. Here, a woman can ask questions about prison dress codes or commiserate through waves of “post-visit blues.” Here, she can share moments of joy without being judged.

(Men are more than welcome in these groups, too, though their presence is relatively rare. As Greenwood notes in her reporting, only seven percent of prisoners across the U.S. are women1, and an even smaller subset of those women meet their partners via pen pal websites.)

I’ll admit I had my own doubts about what kind of personalities I might encounter when I first joined these support groups; the term “prison wife” almost immediately conjured the image of a thrill-seeking young women writing fan mail to convicted serial killers on the evening news. Instead, I found myself growing fiercely protective of the women I met inside. Which is maybe why I first approached Greenwood’s book — originally published under the title Love Lockdown in summer 2021 — with a hint of trepidation.

Greenwood focuses her reporting specifically on couples who are “Met While Incarcerated,” or MWI, a stigmatized brand of romance viewed with skepticism even by some women in a prison relationship of their own. Though I may be loathe to admit it, stereotypes of MWI relationships do exist for a reason. For prisoners facing Kafkaesque pricing on phone calls and basic necessities — or who may have racked up a debt to someone inside — manipulating lovestruck admirers for commissary money can make for a lucrative, and sometimes existential, side hustle; human beings starved for companionship and low on self-regard, irrespective of gender or intelligence, will ignore red flags if the affection lavished on them feels real enough. I’ve never personally met a murder “groupie,” but I have come across a handful of women who readily admit to hybristophilia — a phenomenon defined by the American Psychological Association as “sexual interest in and attraction to those who commit crimes.” (Greenwood doesn’t hesitate to address the “serial killer groupie” cliché in the book’s opening chapters, with a thought-provoking portrait of Samantha Spiegel, deemed “the most successful murder groupie” by SF Weekly in 2010.)

Still, more often than not, I’ve found women in MWI relationships to be fiercely intelligent, witty, and self-aware. “Mama Jo,” an ex-marine and former correctional officer who Greenwood describes as running on “Jesus, coffee, and cigarettes” has given me whip-smart advice over a Facebook thread on more than one occasion. I keep L. - an endlessly dynamic British woman who doesn’t appear in the book but who has become a central character in my own life - on speed dial in my phone; our friendship developed while she was dating a juvenile lifer in Ohio. These are women with an exceptional capacity for empathy and nuance, for accepting outside judgement with grace and holding multiple perspectives at once. By contrast, most producers and writers who set out to tell their stories lean into stereotypes unabashedly sensational and one-note.

I was pleasantly surprised to realize any worries I had about Greenwood’s reporting were overblown.

While she would never call herself an activist, Greenwood’s careful journalism feels like a subtle form of activism in its own right. Though she nods to the more salacious aspects of prison relationships, Love in the Time of Incarceration mercifully steers clear of gratuitous judgment and tired clichés to paint a picture of human beings just as multifaceted as anyone else. Greenwood follows her subjects over the course of five years and, in the course of her immersive reporting, comes to share some of their anxieties — e.g. the feeling of guilt-by-association when she walks through a metal detector for a visit. Her main subjects are also not who you’d expect: Sheila, who now lives with her formerly-incarcerated husband, Joe, in a two-bedroom West Village apartment, fell into writing letters for a prison ministry after a storied career at the New York Times. Crystal, who came from a “stable, two-parent household with high expectations for their youngest daughter,” has been married to her husband Fernando for 27 years; after serving 18 years, he was exonerated with the help of The Innocence Project in 2009. Each relationship highlighted in the book demonstrates the ways love can flourish in a context of constraint — how, when you’re deprived of everyday gestures readily available to couples on the “outside,” senses heighten (I’ll always remember the elation I felt sitting alongside my loved one during a graduation ceremony inside. He’d successfully completed a college-level course offered by a local university; I reached for his hand while the commencement speaker spoke about Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. A correctional officer — the same woman who, in the visiting room, strictly forbade hugs longer than three Mississippi — glanced over at our intertwined hands and, humanely, averted her gaze.)

The flip side of Greenwood’s honesty, of course, is the book will read like an uncomfortable mirror to some women who see themselves in it. She unflinchingly asks questions about race (why do so many white women find themselves tantalized by a reality that is a tragic fixture in communities of color?) and questions whether some women’s relationships don’t belie a deep-seated need for male approval or flirtation with unhealthy levels of codependency. (“Where does one draw the line when nurturing others at the expense of oneself becomes its own pathology?”) At its best, Greenwood’s voice reads like that of a compassionate but understandably concerned best friend. When she finds herself rooting, explicitly or implicitly, for Jo and her husband, Benny, to “make it” upon his release, she wonders if she hasn’t gotten too drunk off the Kool-Aid herself. How much should we judge a life partner based on their past? Things like misdemeanor drug possession are easily left in the rear-view mirror; domestic violence and attempted murder are something else altogether.

“Even meeting Benny, “ she writes, “I couldn’t quite see what all the fuss was about.”

My own relationship ended after a nearly four-year run for reasons both unique and universal, related and unrelated to the challenges of re-entry. There’s something cathartic about re-reading Love in the Time of Incarceration in its wake, although, if we grieve in proportion to how deeply we’ve loved, I never needed a work of investigative journalism to inform me of the book’s most obvious conclusion: love can, indeed, be found in the most broken of places. People fall in love with other human beings all the time; a RAP sheet doesn’t preclude romance any more than a resumé guarantees it.

And maybe that’s the tragedy of it all — stripped of true crime dramatization and MWI shock value, incarcerated love is so widespread as to be considered banal. The Essie Justice Group estimates 1 in 4 women in America have an incarcerated loved one. For Black women, that figure rises to 1 in 2. 95% of inmates eventually return to their communities and, when they do, it’s often women who pick up the pieces and endure the ripple effects of their experience inside. In the absence of substantive re-entry and mental health resources, women become the bread winners, the caregivers, the providers of comfort and respite when their partners struggle to find employment and society opts for stigma over second chances. “Prison wives” are there to open the door when parole officers make surprise home visits at 11 PM; they share the burden of post-incarceration trauma and the feeling their lives can be upended at any time. We enshrine their stories in our literature — from If Beale Street Could Talk to An American Marriage — but overlook their experience in narratives of reform; we both depend on them to care when care is needed and gawk at them when they appear to care too much.

Greenwood makes it clear her book is “not a polemic on prison reform,” even if she “came to witness the singularity of American prisons: their horror, their inhumanity, how domesticated into our culture they are,” even though “there is nothing normal about how we treat people who have (or in some cases have not) committed crimes in this country.”

If only polemics generated the same interest as Prison Bae.

The Prison Policy Initiative estimates 2024 figures fall closer to 10%; in a win for gender equality, “women still represent a larger portion of people in prisons and jails than in previous decades. Moreover, in many states, women's incarceration rates are continuing to grow faster than men’s.”