Wanting to Convince People to Support You is Not "Popularism"

it's just politics, it's just movement building, it's just power

The book club returns in the new year! Your votes have selected No One Will Miss Her by Kat Rosenfield. I will have an introductory post on Wednesday, January 5th (in one week) and our first analysis and discussion post will be on Wednesday, January 12th. So you have two weeks to get the book and do the first reading assignment. I am waiting for my own copy to arrive but I will have a specific page range for you to read for the 12th in Saturday’s digest post. You can safely read any front material and the first chapter if you’d like to start. The book club has been a ton of fun and I’d love to see some new voices in there so please consider jumping in. Book club content is always subscriber-only. Now back to regular programming.

The “popularism” debate is, now, yesterday’s news, although I have a feeling it will crop back up around the 2022 midterms, particularly if the expected happens and the Democrats get walloped. Popularism is an awkward term that stresses the importance of, well, of politicians and political parties being popular with voters. (Crazy.) As Ezra Klein put it in a piece on these themes that centered on the pollster David Shor, “Democrats should do a lot of polling to figure out which of their views are popular and which are not popular, and then they should talk about the popular stuff and shut up about the unpopular stuff.”

Shor has been at the center of the popularism debate for over a year now. David and I go back a long time and I’m glad that he’s become so influential, but it’s odd that he’s become so personally associated with the concept of stressing the popular part of a political agenda. But then, it’s also odd that this even needs a name, odd that “popularism” could be seen as some particular orientation towards politics at all. We live in a democracy, and thus all politics are popularist politics. And I resent the notion that somehow there’s a conflict between being an authentic leftist and trying to emphasize popular parts of an agenda. How else are you going to take fringe ideas and make the mainstream, if not through emphasizing the popular elements, the aspects of left doctrine that have broadest appeal? The left is about shared sacrifice for shared prosperity - everyone contributing so that everyone can be happy and safe. The road there can involve complicated and controversial steps. Including holding views that the public doesn't always like, true, but also including speaking carefully and breaking bread with people we don’t very much like.

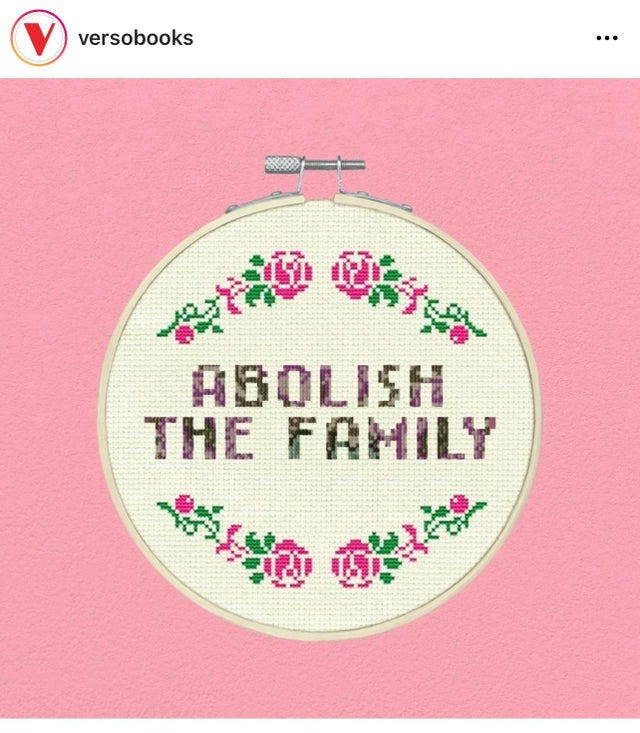

I post the image at the top with a little trepidation. There is this perpetually annoying dynamic that goes on: I will respond to something stupid that’s in my political orbit, then commenters or people on Facebook or wherever will complain that I should not bother because that stupid thing is too obscure or unpopular or whatever. This is quite frustrating for me because

I believe in taking adult ideas seriously even if they do not carry a great deal of political force; I like fringe ideas, hypotheticals, counterfactuals, and other positions that don’t really have particular application to real-world politics

If you’re a Marxist like me then you pretty much have to believe in 1. as we are not a politically relevant force in 2021

The claim that “nobody believes X” is almost always untrue and depends heavily on the individual’s particular viewpoint, media consumption, and political fellow travelers

Niche ideas can have profound effects within specific discourse communities and are thus of interest to people in those discourse communities even if of little salience in the broader world.

And so I share the above image with you. Verso is a small press, no doubt. But it’s very likely the most influential publishing company in the socialist/Marxist world, and since I live in that world, it matters to me. What’s more, this isn’t just something Verso threw out there, but an idea that from my limited perspective is gathering steam among academic leftists. As someone who has spent too many hours of his life at antiwar conferences and organizing meetings I have often seen anti-family rhetoric crop up alongside discussion of what seems like perfectly achievable political aims, like withdrawing troops from some hellish conflict we started or creating social structures that can help people when circumstance robs them of their ability to provide for themselves. I understand that there are cogent critiques of the nuclear family or the traditional family or similar. But some people genuinely, explicitly say that they think the family is an inherently oppressive structure and argue that we should get rid of it. And I wish they wouldn’t! Yes, Marx and Engels took their stab at the family, including in The Manifesto, but everything about post-revolutionary life under communism is a little underdrawn, and if we’re going to go to the mattresses for anything the Papas Smurf argued for, I would prefer it not be the family. Because I like the family! And so does almost everybody else, of any gender, race, ideology, or circumstance. To be anti-family really does strike me as looking for the thing that will piss the most people off, for the least possible political gain. I would prefer it if the most influential socialist press would not casually engage in this kind of useless leftist posturing, when we have so many more important and realistic goals.

For the record, family abolition is a classic motte and bailey - proponents talk casually of ending any sense of intrinsic responsibility between blood relatives, then say that they’re only for getting rid of certain unfortunate consequences of the family when convenient. Here’s a class at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research all about family abolition. The description includes

the foremost popular reaction to the proposal “abolish the family” is one of gut-deep, pre-conscious shock and horror. Even after that initial aversion has passed, sometimes the objection remains: but I love my family, I don’t want to abolish them! In fact, there is little in the history of family abolitionism to imply a ban on living with the people one loves. Rather, the demand, when it has been raised, has been for universal welfare; communal luxury; queer self-determination; a classless society; and transgenerational freedom from emotional scarcity and blackmail

Most of that stuff is just bog-standard leftist ideology; no one need abolish the family to achieve any of it. But saying “abolish the family” sounds radical and thus positions you in a more advantageous light within radical social spaces. This is precisely the condition in which we expect to find the motte and bailey, where extremity is rewarded among an ingroup but rejected among the outgroup. Incidentally, one of the people cited in the class is Shulamith Firestone, who suffered from schizophrenia and likely starved to death in her apartment. Her body wasn’t found for a week. She was a giant of second-wave feminism but she died completely alone. I would suggest that this was a person who could have used more family.

Like everything in American life, the popularism debate is deeply entangled with race. And like everything entangled with race, it involves a lot of people claiming that the other side is saying something that side says they’re not saying. Specifically, the claim has been made that popularism and Shor specifically are racist, in that they supposedly advocate for ignoring the needs of Black voters for fear of alienating white ones. Shor denies that this is his point, and says instead that the question depends on the way that racial politics are waged. Eric Levitz of New York has a useful discussion on those themes here. As is the case with so many discussions that touch on Black voters, this debate is made harder in the progressive sphere because liberals in media and academia often insist on acting as if the median Black Democrat has politics identical to those of a radical BlackLivesMatter activist. In fact, the best evidence we have suggests that the median Black Democrat is meaningfully to the right of the median Democrat writ large - 25% of Black Democrats self-identify as conservative and 43% as moderate, according to Pew. Regardless, I think the basic observation has to be made that in the past couple of years we’ve had a ceaseless ratcheting up of extremity in the racial discourse used by the left-of-center, and very little in the way of material results.

And I think this speaks to Shor’s perspective: it’s easier to take power by avoiding inflammatory rhetoric about race, and then you can do things (not everything that you want, but real things) to reduce racial injustice. If your rhetoric offends too much of the 70% of the electorate that identifies as white1, then you can’t do anything. Of course, if you take this logic far enough you’ll never do anything that doesn’t sit in the dead center of current popularity, which means you’ve forgotten that most of politics is about moving where the median American sits. I don’t pretend that there’s some clear or easy rubric to let us know when we should chase public opinion and when we should give it a shove. But I do know that having this debate isn’t something particular to post-Obama Democratic politics. It’s just what politics is.

I favor a radical agenda; I live in a country that is not (coherently) radical. I say coherently because I pretty much reject the idea that this is a center-right or center-left or center-center nation; opinion polls consistently reveal an incoherent citizenry that wants the government to fund every program you can imagine and also to shrink, that wants Medicare for all but is deeply resistant to banning private insurance, that wants to be strong on defense abroad and to close our bases and bring our troops home. So I don’t truck with the notion that there’s some obvious bright line where popular and possible ends and unpopular and impossible begins. I do, however, recognize that I won’t get a lot of my totalitarian lefty economic changes that I want anytime soon. So I have what I want and I have what I can plausibly get, same as you. What bothers me about the popularism debate is this implicit notion that if you admit that there are things you can’t immediately get and feel that your political movement should prioritize and moderate its rhetoric where appropriate, you are necessarily a DNC-style neoliberal, that this kind of thinking only comes packaged with center-left politics of the type you might have gotten from The New Republic back when it had a coherent political identity. That just isn’t the case.

Everybody, of every political stripe, is perpetually making deals with themselves about what they want and what they can get. The trouble for the left, both the socialist left and the woke left (which are increasingly the same thing), is that they feel so far from power that they don’t think they ever have to make those deals - they won’t get what they say they want either way, so why bother to compromise at all? Why moderate, why reframe, why bargain? But in fact we always have choices. There are always things we do that make our agenda a little more viable or a little less. As a cultural and social phenomenon, I get why so many would be averse to the kind of rhetoric that Shor and Yglesias and others engage in; if you’re a socialist you’ve spent your political lifetime being told to vote Democrat and shut the hell up. But I have felt and will continue to feel that there are all manner of options in-between “vote blue no matter who” and “let’s establish Juche in America within the next year.” Let’s keep our wildest dreams alive, but let’s recognize that yelling about justice does not in fact empower us to get it. Let’s be passionate and ethically uncompromising while we recognize that politics is the realm of compromise and mundanity. Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will, if you follow me.

And if you really insist on coming against the concept of the family, well, you’re going to have to answer to my family….

Why “identifies as white” instead of just “white”? To underline an important fact. Part of the problem with the Emerging Democratic Majority/browning of the United States prediction of Democratic dominance is that this idea stemmed in part from extrapolating the number of mixed-race Americans in the future based on trends in intermarriage. The trouble with this approach is that there are a lot of people who we think of as mixed-race based on their ancestry but who identify as white - and vote like white people do, by and large, rather than like self-identified mixed-race people do.

After 15+ years of being involved in far left/rad left/woke left/whatever you want to call it left organizing and activism, I walked away from basically my entire social circle and 90% of my friends over this issue. I don’t think I’m particularly valuable as an activist (I was only ever the person who took the notes and made the coffee, and I was happy being that person), but I do think that my story isn’t crazy unusual, and I think that maybe the people engaging in this sort of craziness should think a little more about how many more of the note-takers and coffee-makers of the world the left really can afford to lose.

When I try to tell this story I get two common reactions. One is the motte and bailey: “no one” is making the crazy arguments I cite to, and I must be either stupid or deluded to think that they are.

The other is a No True Scotsman argument: I must not have really been committed to any of it in the first place. I was secretly conservative all along!

What actually happened was that the craziness of much of the rhetoric started me off with questioning my entire belief structure.

Much like a fundamentalist Christian might start asking themselves whether Noah *really* took two of every kind of animal onto a literal ark that floated on the face of the earth for however many days (and if so where did they store all the food???), and find that one question leads to another and suddenly the entire edifice of their faith has been lost, I found myself asking whether it was *really* my internalized privilege and white fragility that made me want to cry when I was called out in front of 300 people for mixing up the words systemic and systematic, and from there I found the entire structure of belief collapsing.

Some of my beliefs have been retained to be sure, since I did in fact sincerely believe much of it: I would like to see higher caps on immigration from Central America, as a random example.

But I can’t imagine ever being able to actually work on the issue with lefty activists ever again because the degree of purity testing is so high. Everyone is an activist for everything and wants to test everyone else on the subject, so I doubt I could attend an organizational meeting on immigration policy without being required to nod along with all sorts of opinions I no longer hold.

I confine my volunteering to soup kitchens etc these days, which is fine, and again it’s not like I think I am some terrible loss to activism; I just took the notes and made the coffee.

But it seems significant to me that I was driven out, first because it happened to me and I lost a lot of friends and I’m not over it yet, but also because if you can drive out a fifteen year note-taking veteran, who else are you driving out, or never bringing in? Is this really the way to change the world?

And because I do still care about a lot of the concrete goals, I possess a fury born of heartbreak that the only responses I typically get are either pretending that nothing untoward is happening, or suggesting I must have been a cuckoo in the nest all along.

“Abolish the family” might sound like something that will never happen (because it won’t happen) but some activists on the left are increasingly hostile to parents / parenting in a way that voters notice and loathe. I’ve been thinking about what happened in the Virginia election, especially after reading Matt Taibbi’s reporting on Loudon County – parents were shut out and demonized by school officials, and they were pissed and voted for Republicans.

I’ve also been troubled by the story of 2 teachers in California who bragged about the tactics they used for their LGBTQ club at their middle school (and have since been suspended from the club pending an investigation). The short version is that people are angry because they stalked the kids’ online activity to recruit members, and because of their efforts to conceal kids’ participation from parents. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Two-California-teachers-were-secretly-recorded-16732562.php

As a gay person, I’m obviously sympathetic to adolescents who are afraid to tell their parents they might be queer. Supportive teachers meant a lot to me and my queer friends. So I’m generally supportive of teachers providing a safe environment and not tattling to parents.

But what bothers me is how these teachers seemed to relish building a secret community that shut parents out. They didn’t encourage any kids to talk to their parents (surely not every single one was abusive?) They sound like they’re enjoying the fact that kids confide in them instead of Mom and Dad, because they get to feel morally superior and they don’t have to worry about anyone challenging their amateur diagnoses of troubled children.

Parents aren’t wrong to think some on the left are actively working to undermine them. When the family is perceived as a problem (parents aren’t woke) some activists are happy to sideline them in favor of their politics. “Abolish the family” won’t happen like “abolish the police” won’t happen, but the slogan reminds voters of real things going on that they hate.