If you missed it, please check out my recent piece for Vital City.

Education may be the issue that I’ve written about the most in my career, at least on my own blogs and newsletters. It’s the topic I’m the best credentialed in, whatever that means, and I have taught many classes and worked in various capacities in schools at several levels; I also come from a family of educators. Beyond those things, though, I think education is a perpetually fascinating topic which brings some core elements of modern society into friction with each other, sometimes even productively. Education is the ultimate proxy issue, the issue we use to talk about core societal dynamics that many in our society would otherwise prefer to avoid, most notably racial issues but also gender, class, opportunity, the definition of success. American education is, as they say, a rich text.

Education discourse is caught in many contradictions and tensions, including

Our education system is presumed to serve the essential function of sorting high school graduates into colleges and college graduates into jobs commensurate with their ability, but modern norms prevent us from acknowledging that for this system to work, there must be students who are at the bottom of the distribution - that is, bad at school

Education is purported to be a great equalizer even while it fulfills the aforementioned mission of sorting good students from bad, a central internal tension that results in endless controversies like those concerning the SAT

Education research has profound and unique challenges in terms of basic research design and empirical principles, which I detail here

Issues of schooling highlight the odd reality that many people have limitless compassion for children and will support all manner of programs to help them but lose all of that sympathy once someone turns 18, putting intense pressure on the system to promote social justice while they’re young

Basic resource questions, like “Should the best teachers teach the best-performing students or the worst?,” go unanswered even in elite spaces that regularly debate education, largely because those questions are complex, uncomfortable, and politically unpalatable1

In recent decades our school system has been purported to be the key mechanism through which society moves people out of poverty and promotes equality, tasks which schooling was never designed to accomplish.

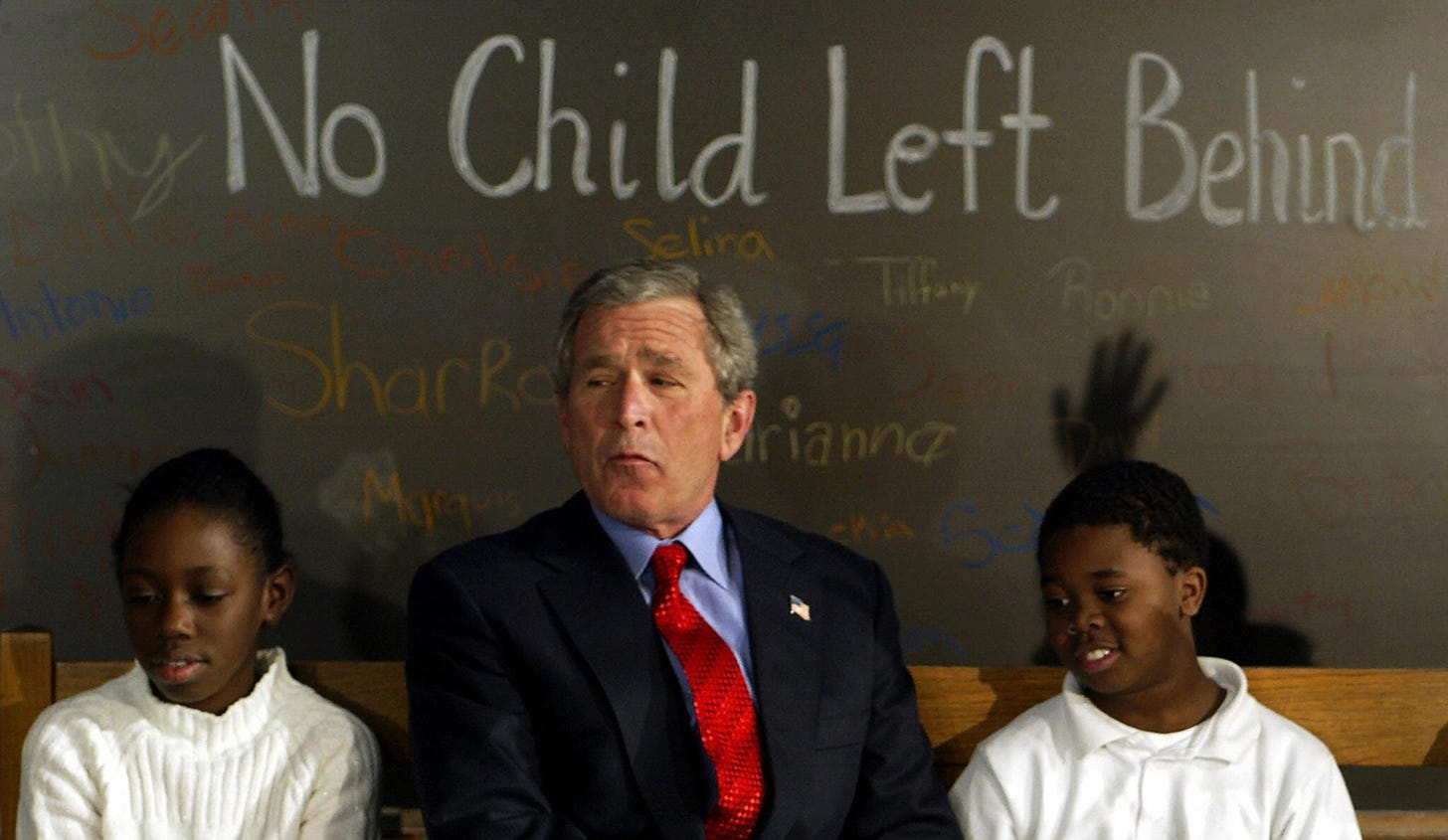

Nowhere are the pathologies of our education discourse more apparent than in the school/education reform movement. By that I mean the somewhat-amorphous but impossible-to-ignore effort to dramatically change American schooling that attracted a remarkable amount of attention, funding, and influence in the 2000s and 2010s. This powerful movement still exists, albeit in a diminished state. Typically associated with neoliberalism/market liberalism/Democratic technocracy etc, the education reform/school reform movement seeks to “fix” American education with reforms that stress accountability, choice, and using the power of markets to improve academic outcomes. Their consistent targets are teachers and their unions, arguing that endemic failures within our country’s poorest districts are primarily the fault of feckless and untalented teachers who are protected by their unions and teacher tenure. They have, at times, venerated heroes like Harlem Children’s Zone school Geoffrey Canada, former Washington DC public school chancellor Michelle Rhee, and Obama administration Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. They tend to deploy a maximally righteous political rhetoric, insisting that any objections to either the fairness or efficacy of their professed solutions are simply excuse-making.

Some key ed reform efforts include

The dramatic expansion of America’s (almost always non-union) charter schools, which is to say, schools that operate with government blessing and often some degree of government oversight but outside of most local school district leadership structures and, crucially, without falling under the collective bargaining agreements that teachers unions strike with traditional public school systems

Merit pay initiatives that seek to reward teachers based on the performance of their students, rather than a conventional salary structure that includes bumps for seniority and sometimes for additional education; these systems often are tied to various value-added models and similar efforts to fairly and accurately assess how well teachers are teaching

The establishment of universal standards, common assessment methods, and shared national benchmarks for success, based on the notion that there’s too much variability from state to state and district to district in what students learn and how that learning is measured; the Common Core represents something of an ideal for the movement, both conceptually and in its remarkable success in being passed in a large majority of the states in the nation (in part because there was so little public input or debate when the standards were being adopted)

Relentless census-style standardized testing

Some school reform types have traditionally supported private school vouchers, while others have not

Some school reform types have traditionally supported abolishing teachers unions and teacher tenure entirely, while others have not

In general, education reformers have demanded systems with more latitude on the parts of principals and superintendents to make pedagogical and administrative decisions without being hampered by regulation, union contracts, and normal procedure; in practice, this mostly means conflicts with teachers over their rights and due process as employees.

Perhaps the ultimate school reform text is Davis Guggenheim’s documentary film Waiting for “Superman,” which was released at the zenith of school reform mania in 2010. In it, Guggenheim relentlessly insists on a maximally simplistic vision of education and what supposedly ails our schools. In the clip above, you can see what this looks like, an absurd visual metaphor of education amounting to teachers just pouring learning into the pliable brains of children. Anyone who has ever taught anything, or who’s remotely familiar with the educational research record, could tell you that this is a faulty depiction of how teaching works. But treating educational issues as all inherently simplistic is a core element of school reform rhetoric; doing so helps reformers ignore the vast number of complications and inaccuracies that have been identified in their thinking. Near the end of the film, Guggenheim yells in full righteous fervor, “Don’t tell me these kids can’t learn!” This is the ed reform movement’s ethos in a nutshell: sanctimoniously shouting down opposition in lieu of argument, using the poor students being left behind as rhetorical cudgels.

For some additional background, I recommend Matt Yglesias’s five-part “The Strange Death of Education Reform” series, the first of which is linked above. While Yglesias and I have some profound disagreements on this topic, and I personally came in for a little sass in the series, I think it’s a very useful primer on this political movement and what’s become of it. It’s called “The Strange Death” because, in a very profound and totally unexpected way, the education reform movement went from an unstoppable political force to an afterthought. In the early 2010s I had pretty much resigned myself to the belief that, given the bipartisan fervor for school reform that had gathered, teachers unions and tenure and various other teacher protections were sure to soon be a thing of the past. Successive presidents, a Republican and a Democrat, had both endorsed more or less the same anti-teacher, pro-reform politics. Prominent school systems were embracing merit pay and various accountability measures. Many liberals insisted, as did Barack Obama, that school reform was our great modern civil rights movement. And then… poof. In very short order, the juggernaut was sidelined, marginalized, disavowed. The way 9/11 went from the most important political issue of my 20s to a relic in my 30s will always be the most remarkable evolution in politics in my lifetime, but the sudden sinking of ed reform happened faster and was almost as stark.

What happened? As I said, read Yglesias’s pieces if you’re inclined. Short version, I think the most important contributor to this development was the election of Donald Trump, which ramped up partisanship and made bipartisan movements unpalatable. Democrats had helped George W. Bush with his disastrous reform efforts, but personal revulsion towards Trump helped ensure that wouldn’t happen again. When Trump nominated archenemy of public schools Betsey Devos as his Secretary of Education, many feared the worst. But Trump transparently did not give a shit about education, and Devos’s ugliness ultimately wore off on the school reform movement in a drastic way. No Child Left Behind had been an abject disaster and was considered so, by the 2010s, even by many of the bill’s old supporters. And as Education Realist has argued, money played a big role in opposition to endless state standardized testing; NCLB had provided funds for the initial development of tests, but not for regular administration, leaving a significant financial burden on states that they have been eager to get out from under. Conveniently, the opt-out movement of parents who were frustrated with all the testing helped give state politicians cover to agitate in that direction. And by the late 2010s, the social justice philosophy had come to dominate left-of-center Americans, at least in elite circles, which led to broad adoption of Ibram Kendi-style resistance to achievement gap rhetoric in toto.

More than anything, though, I think that the school reform movement hit a wall because its prescriptions kept failing. The fiasco in the Newark public school system, and the vociferous opposition of parents there, was a bellwether. Examples like the all-charter New Orleans system, implemented after Hurricane Katrina, led to appropriately jaundiced views of charter schools. They once talked about the “miracle of New Orleans”; today about half of those schools receive a D or F grade on Louisiana’s scoring system, which feels decidedly non-miraculous. Maybe most damning has been the endless drip of mini-scandals over the way charter schools cook the books to get the students they want. From this ugly Reuters investigation to the ACLU finding that more than 250 schools in California inappropriately manipulating their admissions to the sky-high attrition rates of the vaunted New York Success Academy and KIPP systems, on and on and on…. These constant efforts to cherry pick the best students prompt an obvious question: if the charter school argument is fundamentally correct, why would these schools need to engage in such manipulation?

Nothing is ever dead in American politics, though, and I expect ed reform to make a comeback under a potential Kamala Harris presidency. So here are my basic arguments against education reform philosophy.

American students do better than you think. Crisis rhetoric is draped all over the ed reform movement, with not just ordinarily-excitable politicians partaking but often stuffy nonprofits and serious wonks as well. Many Americans seem to casually believe that our education system is a top-to-bottom basket case. But this simply isn’t so. America’s top performing students are, arguably, the very best in the world, with students from our public school system frequently winning top international academic competitions. Our universities are still widely perceived internationally as the best on the planet, and of course a great deal of that value stems from the quality of our top students. We produce a vastly disproportionate number of the world’s top scientists, professors, engineers, doctors, lawyers, etc. There is no coherent argument to be made that our top-performing students are anything less than stellar, let alone evidence of crisis. Meanwhile, while our median student has been the result of relentless fretting, the truth is that their performance is not worthy of sustained alarm. International comparisons like PISA tests, while not especially encouraging, are better than you might guess thanks to the crisis narrative. It’s also important to note that even the largest international comparisons don’t include data from a vast number of countries in the world, almost all of which are considerably poorer and less developed than the United States and which would perform far worse if included.

To the degree that our median student’s performance is concerning at all, it’s largely a product of our actual problem: very deep and persistent trouble among our lowest-performing students, the performance of whom students is so bad that it drags down our averages considerably. These problems are very often represented as being matters of urban Black and Hispanic school districts, but it’s worth saying that much of the problem is also found in suburban and rural districts, as well as majority-white ones. (Up until recently, a plurality of struggling students in American schools were white, and this has changed because of evolving American racial demographics, not an improvement in white student scores; it remains true that a very large portion of our struggling students are white, despite assumptions otherwise.) These deep and persistent problems in our poorest districts are of course a social problem, but they invite immediate consideration of whether it’s a coincidence that the students who face the most intense social and economic problems also perform the worst in school.

American students do OK. On a bang for our buck level, OK is really weak tea, but then past a certain minimal level more money spent on education has no effect on educational outcomes.

There’s no glorious past of American education to compare ourselves to. People frequently talk about bad academic metrics as evidence that our country has fallen from its once great heights. This complaint is based on the faulty premise that we were once really good in international education comparisons. In reality, America has always sucked. Since rigorous international rankings started to appear in the 1960s, we have always finished near the bottom - again, of countries that have been measured, which is an important caveat because we would beat the pants off of most countries in the world. And for the record our previous shitty scores occurred during our periods of greatest scientific and economic dominance, such as in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the Apollo missions amazed the world. Because you don’t need everyone to be smart, you just need your top performing 10% or 5% or 1% to be really smart, and we’ve got that.

Expecting markets to fix education makes no sense. Perhaps the most common claim of the education reform movement is that we can fix education by creating competition between schools that prompts innovation and reveals excellence, bringing the power of markets to bear on the problem. Just like with a widget factory! Schools will do a better or worse job, the metrics will reveal which, parents will send their kids to the good schools, the bad schools will either adapt or be forced to close. Simple!

The first response should be fairly obvious: people have been applying market forces to schools for a long time. In fact, before publicly funded and provisioned education became a thing in the 19th and 20th centuries, every school was subject to market forces! Were there any bad students in the old all-private system? Yes. Were there stubborn demographic differences in outcomes? Yes, although of course most students in underrepresented groups did not have access to education at all. There are thousands of private schools in the United States which must make money to stay in business. Do they eliminate the gaps seen in public schools? No, adjusting for the massively unequal student populations, private schools educate no better than public. There are thousands of private colleges and universities in the United States, and though most are technically nonprofits, they still very much follow the profit motive that powers market effects. Are there failing students in private colleges and universities, which must attract students or close their doors? Of course there are. Are there consistent demographic gaps in private colleges of the type that have dominated education reform rhetoric? Yes, there are. Market forces have not closed such gaps.

The real question is… why would that work?

A child’s brain is not a widget made in a factory. We do not have direct access to the cognitive and emotional machinery that governs our academic ability. All of our educational tools are operating several layers away from the factors that we hope to influence. You can perform the job of teacher at the highest level, but if you have a student who has a lower level of natural ability, or who suffers from the depravations of poverty and an unhealthy environment, or who faces abuse or neglect from their parents, or who has a cognitive or developmental disability (diagnosed or not), or who simply doesn’t want to work, actually-altered outcomes are not at all guaranteed. A factory owner controls every stage and aspect of a widget’s development; teachers and schools get students after five years of development, by which time the racial achievement gap has already appeared, and then have six hours a day for ~180 days a year to attempt to close it. Teachers also have a social and moral responsibility to teach the high-achieving kids as well as those who perform poorly, which helps ensure that gaps don’t close. The market mechanism can only work when the entrants in a market have a reasonable amount of control over the “product” that they’re selling. But teachers just don’t have that kind of direct casual influence.

The measurements are wonky. Yglesias succinctly summarizes a core element of education reform as “measure learning, apply consequences.” The trouble is that even the most rabid ed reformer would concede that different classes and schools have profoundly different average levels of student ability, meaning it would be senseless to judge them simply with summative metrics. For this reason, ed reformers long advocated for “value added” measures to assess how much a given teacher or school’s students were learning. The trouble with that is the inconvenient fact that no one knows how to do that fairly and effectively. Critiques of value added modeling are legion and damning. When implemented, such as in merit pay systems, the outcomes have often been entirely out of keeping with the opinions of principals and peers in terms of who is a good or bad teacher. More concerning, VAMs often have disturbingly inconsistent findings, suggesting that a teacher is great at their job for their first period class but awful for their third period class, naming a teacher the best in a school one semester and the worst the following semester, etc. On the macro level, research has found that major efforts at teacher evaluation have had no positive impact on student scores. Particularly embarrassing, researchers showed that a real value added model could be used to assert that teachers have a measurable impact on student height, which demonstrates the degree of wiggle these systems need to generate their ratings. The whole thing is a blind alley.

Educational assessment of students is something we do very well. Assessing teaching is not, again because we’re trying to measure a kind of influence that’s profoundly intangible, inconsistent from student to student, and subjective.

We live in a profoundly unequal society. Not a lot of complication here - the United States is riven with deep inequalities that make education difficult for some and which make fairly assessing school performance close to impossible. It’s true that people often generalize too broadly and simplistically when it comes to the direct educational impact of poverty, but it’s also certainly true that a vast number of variables are associated with income and wealth inequality and racial inequality, and they certainly have an impact. (Lead exposure and prematurity, for example, are sufficient to drag average performance into very bad territory.) This makes many of the typical comparisons worthless. Finland is widely considered to have the best education system in the world. Finland’s Gini coefficient, which measures economic inequality, is .28; in the United States, it’s .47. Finland’s child poverty rate is 10.1%; in the United States, it’s 16.3%. They have among the most generous and effective social systems in the world. Do these things explain all of the difference between Finnish and American outcomes? No. Do the differences render casual comparison pointless? Yes. Reformers love to shout “No excuses!” but doing so doesn’t actually make the inequality go away.

Individual students have different levels of individual academic ability, student-side variables dominate school-side variables in influence, and thus expecting all our kids to meet arbitrary benchmarks is folly. My thoughts on this are pretty well known at this point: an overwhelming amount of evidence suggests that individual students have individual levels of intrinsic or inherent potential, likely genetically influenced, which varies dramatically from student to student. I frequently have to remind people that, however important various group achievement gaps are, gaps between individual students are far larger; the gap between the best-performing and lowest-performing kids from a particular racial group is several times bigger than between any two difference racial groups. Individual variation between students is massively important for the overall performance distribution - indeed, it is the performance distribution - but is curiously absent from much of the debate about our schools. If individual students really do vary in their underlying potential, any attempt to assess student performance that does not account for this variation is flawed and will result in bad policy. And fully grappling with the fact that individual students do not fully control their own academic outcomes has profound moral implications for our meritocratic system and the economy it rests on.

In the above piece, I lay out a massive amount of evidence demonstrating that the distribution of students in the relative performance hierarchy is remarkable stable and resistant to change through a variety of means - that is, while some individual students will move up or down the distribution dramatically, in remarkable majorities students will occupy the same position relative to their peers as they move through school. Students slot themselves into a given performance band in kindergarten and tend to stay in that band through college; there is some evidence that the correlation between past performance and future performance increases as students age, such that movement within the distribution becomes more and more unlikely in later grades. This does not necessarily prove that students have an inherent or intrinsic talent for school, much less that this talent is genetically determined, but it’s powerfully difficult to come up with another explanation that fits the facts. And, obviously, this all has profound implications for the school reform story: if different students have different levels of potential, expecting teachers and schools to create equality (whatever that might mean) or to raise everyone into excellence (whatever that might mean) is asking them to do the impossible.

You don’t have to turn everyone into an A student to fight poverty, promote equality, and improve mobility. Core to my overall perspective is that the modern tendency to see education as an effective vehicle for promoting equality and justice is badly misguided. For most of the world’s history, education was not seen as having this purpose; the widespread adoption of this worldview corresponds with the neoliberal turn and its antipathy to conventional leftist solutions like a robust labor movement and a generous social safety net. Acknowledging that schools can’t fix poverty or inequality doesn’t require that you give up. It simply prompts you to invest your efforts in solutions that are actually solutions.

Schools provide many wonderful benefits. I’m not going to go into my broader solutions for what to do with public education, which is a whole other ball of wax. But I would like to stress that, once we stopped insisting that schools fulfill a function they simply can’t, we can focus instead on the many wonderful things that schools can do. Schools can be warm and safe and enriching places for children to go; schools can prompt the kind of learning that enriches and provokes curiosity and entertains, when we aren’t obsessed over test scores; schools can show young people all the many ways they can be a valuable and productive member of society; schools can promote social and personal development; schools can open myriad doors to different kinds of experience, to different hobbies and interests, to new ways of thinking and understanding. And, yes, those students who are interested in academics as a competitive pursuit designed to move them up in the meritocratic rat race can certainly use school for that purpose too. The problem is that not everyone is equipped for that and, more, not everyone wants to take part in it. We need to get past the notion that the only fulfilled life is one that goes through a top twenty university and ends up in a Fortune 500 company, and no force in modern American political life has done more to insist on those bad priorities than the school reform movement.

A good example of the basic incoherence at play in how we talk about education can be found in an old New York Times piece on New York’s flirtations with “school choice,” which I discussed here. There’s nothing particular remarkable about the story in question. But as I say in my post, the piece reflects basic incoherence in how elite institutions and individuals think about what school is for, who it should serve, and how it should work. To a remarkable extent, even those who spend a lot of time reading and thinking and arguing about education have no defined what success would entail and how we would know it when we have achieved it.

"Should the best teachers teach the best students"... we have collectively answered that for athletics and music, and probably the rest of the arts, the answer is a resounding "yes." But somehow for mathematics it's not considered obvious that the best math students might thrive under the best math teachers.

Thanks as always for trying to make the public understand what education IS, not what we want it to be. That's a hard lesson, and too many people don't want to learn it.

As a former teacher, I think I understand why a little bit. I remember having the "Waiting for Superman" model drilled into me when I was getting my education degree, filling students' heads with knowledge. That and the entertainment counterpart: You MUST keep their attention, keep them entertained; that's essential.

I thought both models had problems, but I wanted to graduate. But after a couple of years of teaching, a different model occurred to me. In my third year, I opened each class, after taking roll, with silence. I stepped in front of my desk, and just looked at the students. This was high school sophomores, and after a bit they giggled and fidgeted a bit, but that did get their attention.

Then I pulled out my wallet (still silent), took out a five dollar bill and laid it on my desk. Then I stepped aside a bit. More giggling and fidgeting, and "what the helling?" but definitely more attention.

Next I said, "Anyone who wants that can take it."

A lot of "Is he serious?" looking at one another, some actual laughing and looking at me quizzically.

I told them I meant it. Anyone could take it.

There was a little more curiousity, and then a brave student or two got up. In some classes is was just one, the other classes had a couple who raced up to get it. In all cases they looked at me one more time to silently ask, "Really?" I nodded and they went back to their desks.

Now everyone wanted to know what was up.

I said, "That's my philosophy of teaching. It's not exactly something I give to you, it's something I offer. But you have to take it. I'll be placing five dollar bills, and tens and hundreds and thousands up here all year long, making them available to you. But unless you take them, unless you make the effort to make them your own, you'll be leaving money on the table. You may not be able to tell at first how what I'm offering you will be helpful in your life, and maybe it won't. But what I'm doing here has been the kind of thing that made millions and millions of people better than if no one had offered it."

I've sure I've cleaned up that speech over time, but it's the model I still think is right. You're also right that a lot of kids won't be able to understand what that means, or will mock it defensively. I did have students like that, who I worked harder with. But it did help instill the notion that education isn't a passive idea, it's an active one on my part and on theirs.

The end of the story is what I'm sure you'd expect. My first day was talked about among the students, it got back to the administration, and I was called in. "You can't be giving students money in class," I was told sternly. I explained the motive, but of course the bottom line was that it would make other students unhappy, there would be complaints, it wasn't teaching them the right lesson, etc.

So it was a one-time experiment, and I didn't try it again. A few years later I left teaching for other battles with administrators -- I was too young to have learned myself how to deal with bureaucracies, and went in another direction with my life.

But teaching is still the most valuable job to society that I've ever had -- well worth the much, much higher salaries I had later in life. And it's still something I discuss with other teachers I encounter. Most seem to agree that it is a more helpful model for kids to understand -- that they're not passive players in education, they're its primary actors. I think kids need more of that.

It's a lesson I wish I could teach to many adults in the education system, particularly administrators.