My first book was an orphan before I wrote it; the guy I sold it to at St. Martin’s left the company a couple months after I signed the deal, seemingly under acrimonious circumstances. I think the book may have been the last released under that imprint. The people at St. Martin’s genuinely did heroic work with editing and promoting it, for which I’m forever grateful, but it really was facing far from ideal circumstances. (In part because of me and all my stuff, to be clear.) Another core problem was that I never came up with a good elevator pitch for it; that is, I didn’t and don’t know the best way to summarize its core argument. I have like three or four different ways that I talk my way through the book’s themes when I’m asked to explain it. This is, I’m afraid, not ideal from the perspective of trying to sell big-think nonfiction of this kind. Here’s a good explanation, but again it’s in the thousands of words. Let me try a bulleted list.

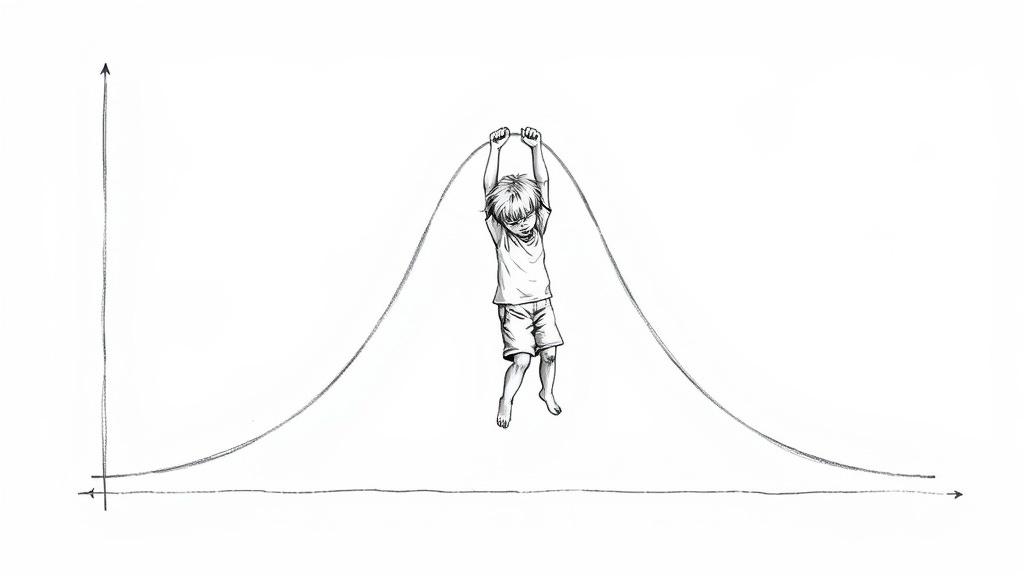

There’s an enormous amount of empirical evidence showing that very early in formal schooling children gravitate towards a given performance band in school - that is, to a particular position relative to their peers in a quantitative performance distribution such as grade point average, state standardized test scores, or similar - and stay in that band throughout academic life, with remarkable fidelity. Kids perform to a particular level of accomplishment in kindergarten and, in great majorities, stay at that level until they finish school. (That is, high-performing kids stay high performing, low-performing stay low, kids from the 25% very rarely make it to the top 50%, etc.) Data gathered the summer after kindergarten allows us to predict how students will perform in college, with considerable accuracy; third grade reading group, a very coarse predictor, nevertheless provides enough information to make pretty good assumptions about who will do better or worse in school even into adulthood. Yes, kids learn things they didn’t previously know, but as they age and learn they tend to stay in the same performance band, and it’s relative performance that’s reward in the labor market and larger economy. Here’s a ton of references if you’re curious.

Essentially no school-side interventions work to change quantitative outcomes; that is to say, despite expending vast amounts of money, time, and effort on hundreds of potential ways to “fix” education, the relative performance distribution is replicated. Absent truly drastic life changes like being removed from an abusive environment or suffering a terrible trauma, most kids stubbornly occupy the same relative ability level throughout academic life. Interventions that are purported to change relative performance at scale inevitably fail over time, and previous positive results are revealed to be the result of selection effects - i.e., of hidden non-random sorting - or out-and-out fraud. Small pilot programs reveal gains so large that they should not be taken seriously by anyone, yet they often are, right up until attempts to scale such programs demonstrate no actual benefits. These failed interventions range in scale from small (expecting piano lessons to improve math skills) to medium (the eternal hope of pre-K as the solution) to large (pinning hopes on school quality, despite the fact that many studies demonstrate that truly random assortment of students into schools of different perceived quality has no measurable impact… because there is no such thing as school quality.) Nothing works.

The only reasonable inference to draw from this reality - from the fact that students gravitate to the same level of performance throughout life in large majorities, even in the face of huge changes to environment, family, and schooling - is that there is such a thing as a generally-stable inherent individual level of academic potential. Individual, in that I’m not talking about any kind of racial or gender or other group differences but rather differences from child to child, student to student. Inherent, in that it is a stable property of individuals, not the sum of environment or family culture or chance influences but reflects some intrinsic property internal to the individual. It seems very likely that this property is heavily genetically modified, with the obvious explanation that our brains are the seat of cognition and are organs built by genes and thus subject to genetic influence like the rest of our bodies. But that’s all very controversial, and anyway it’s not necessary to believe in a genetic influence on education to believe that we all have some underlying level of natural or intrinsic academic talent. It is of course not the case that the presence of inherent potential means that no exogenous variables matter; I assure you, if you expose a child to serious lead exposure, that influence will be measurable. But the tendency in contemporary American society is to ascribed everything to schooling and environment, when individual talent is likely the dominant factor in determining who sits where on the performance distribution.

The consequences of the existence of such a property are wide-ranging and serious, not just for our education system but for our entire economy, thanks to how the former does so much to determine outcomes in the latter. Among other things, the concept of moral luck looms large; if our academic ability has profound influence on our economic outcomes and our academic ability is something we have little control over, it undermines a great deal of the moral justification for our system. In less grand terms, such thinking suggests that the ever-more-exacting standards demanded by many reformers, exemplified by the Common Core, are exactly the opposite of what we want. There’s also a glaring need for an economy that’s fair to people who aren’t naturally gifted in the academic skills that are most valuable in our system. You can read all about it in the book.

There’s a lot of stock responses to this. Most fixate on the possibility of genetic influence on educational outcomes; some point out that such influence is currently unproven, which is true for now, while others insist that it’s racist/eugenics/fascist/etc to even consider the possibility. Some of the more traditional school reform types just chalk all of this up to “excuses,” the way they do for everything. Some argue that if the above is true, we should respond by defunding the public education system, but as I say in the book I don’t think this follows at all. And some people make versions of the following points.

There are multiple intelligences, many different ways to be smart

No test or other form of academic assessment could ever perfectly or completely capture all of our cognitive strengths and weaknesses

The intellectual or academic skills and abilities that are perceived to be valuable by society are not transcendent or eternal but rather context-dependent, dependent on human uses and historical era.

To which I say, yeah, of course. That’s all true. It’s just that none of it contradicts anything I laid out up above.