Slowly, Imperceptibly, the Hegemony of the Cult of Smart Loosens

but almost certainly not in a productive way

Recently Alan Jacobs did me the favor of summarizing my philosophy of education, which is useful because I always have such a hard time doing so myself.

In any given population, the ability to excel academically (whether or not you call it “intelligence”) is, like almost all other human abilities, plottable as a normal distribution: that is, a few people will be really bad at it, a few people will be really good, and the majority will be somewhere near the middle.

Because some people are simply better at school than other people, any pedagogical strategy, practice, or method that improves the performance of the worst students will also improve the performance of the best students; this means that “closing the performance gap” between the worst and best students will only be possible if you use the best strategies for the worst students and the worst strategies for the best ones — and even then the most talented students will probably adapt pretty well, because that’s what being a talented student means. (N.B. I am assuming that “Harrison Bergeron” strategies will not be employed, though maybe that’s not a safe assumption.) Another way to put it: if every student in America were equally well funded and every student equally well taught, point 1 above would still be true.

Resistance to these two points is pervasive because we collectively participate in a “cult of smart” that overvalues academic performance vis-à-vis other human excellences. That is, because we value “intelligence” as a unique excellence, necessary to our approval, we cannot admit that some people simply aren’t smart. (By contrast, we have no trouble admitting that some people can’t run very fast or lift heavy weights, because those traits are not intrinsic to social approval.)

That’s quite elegant and an accurate summary of what I’ve been talking about for a long time. There are of course a number of challenges to my position, though they don’t usually emerge from any official or high-profile people or publications - to rebut me would be to give my arguments a chance to be heard, and there’s a real wall of silence about these issues. I’m not impressed by most of the stock answers to my points, in large measure because they pretty much universally depend on incoherent perspectives on the distribution of academic performance, which is what this is all about.1 Most people I argue with acknowledge that there is at least to some degree such a thing as natural academic talent, a predisposition to a particular performance band, although some don’t. Most are attached to the idea of academic excellence and refuse to give that up. And right there, you’ve got irresolvable contradictions; if there is such a thing as academic excellence, then there must necessarily be a distribution of performance and some students at the bottom of that distribution - some students destined to be Left Behind. If there is any such thing as latent academic talent, then there are students who don’t have it, and the pretense of universality and equality fall away. Etc.

Still, the Cult of Smart is baked into our economic system and thus challenges to it are reflexively deprecated. As I demonstrate in the book, the “college for all” mindset” really got going in the late 1970s and 1980s, right as the neoliberal consensus was capturing American politics and policy. Which makes sense; when you dismantle the labor movement at the behest of large corporations, you need to at least come up with a notional or theoretical vision of how ordinary people can achieve the good life. And college was sitting there, for most of our history only embraced by a small slice of the population; the policymakers needed a good story about opportunity and broadly-shared prosperity, and the colleges certainly wanted more public money and more customers. The vision of every citizen as a busy little meritocrat that climbed up the ladder with hard work and study flattered our self-conception as a nation of go-getters. It’s a rearticulation of the American dream, just now filtered through the lens of “the knowledge economy.” And college is a legitimately great time for many people, fun and genuinely enriching, so it wasn’t hard to convince far more people to sign up. All that added expense could be parceled out as long-term debt to a bunch of 18-and-19-year-olds for whom the long-term didn’t seem to exist.

The trouble should have been obvious. The value of a college diploma is derived from its scarcity relative to the number of jobs that call for one; if you flood the job market with degrees, the value of those degrees will necessarily decline. (Contrast with labor unions, which grow more powerful the more people join them.) Meanwhile, if there is in fact such a thing as an inherent or intrinsic or natural tendency to be good at school, then this whole setup has cursed a lot of people to hard lives based on factors they can’t control. But with the American vision of success having evolved to add college success to the life plan of job, marriage, kids, and with the neoliberal consensus going utterly without challenge in our political system, there’s been no room for broad public debate on the basic sense of this whole operation. Of course, many millions of students failed to succeed in school, seeming to undermine the system. So the school “reform” movement stepped up to blame those lazy teachers and their greedy unions for failure, against all evidence. And any notion of differences in individual academic talents was swept up in arguments about pseudoscientific racism, with the baby of the common-sense reality that different individual people have different levels of academic talent being thrown out with the bathwater of race science. This was all a matter of true bipartisan consensus, and for as long as I’ve been researching and writing about it there’s been no hope of carving out space for alternative points of view on education and meritocracy.

But now maybe, just a little bit, we are?

Dana Goldstein has a piece in the Times about how the long-sacrosanct goal of “college for all” has begun to be challenged. It’s being challenged in dumb ways for dumb reasons, driven by Trump-era resentment towards elites and those with left politics, but it’s at least being challenged. This is all articulated through a rising call for alternatives to college, such as job placement programs and trade school and similar. The value of such alternatives is always contextual and subject to some of the same distributional issues as college - the more and more people you send to electrician school, the more the financial value of being an electrician is eroded - but nonetheless we need alternatives and I’ll take some more investment in them even if it’s mostly a matter of Republican teeth-gnashing. I’m just not confident that this shakes out with actually beneficial policy changes.

Of course, Goldstein (whose work I like) can’t come out and say the quiet part out loud: that the consensus has started to slip in part because it’s simply become too obvious that differences in individual talent are real and thus the system cannot actually push everyone through “the college pipeline,” unless standards are reduced to a ludicrous degree. We lived through a long lull for the school reform movement in recent years, obvious and meaningful enough that Matt Yglesias wrote a good series about it. There have been many culprits identified for why school reform fell on hard times, most of them political; the most prominent and powerful critics of public schools and teacher unions stopped being Barack Obama and Arne Duncan and became Donald Trump and Betsy DeVos, changing the culture war valence. Social justice and equity politics were always skeptical of the achievement gap narrative. These were indeed all relevant for the politics. But there was another obvious reason why the movement to blame teachers and replace public schools with charter ran out of steam: they kept failing to live up to their incredibly outsized rhetoric.

The reform movement had bipartisan (though not uncomplicated) support, and they scored many policy victories. And, conspicuously, this did not correspond with any educational gains commensurate with the resources involved and the political capital expended. Because the problem was never schools. The problem was a) vast differences in structural social conditions between races produced racial achievement gaps that prompted a great deal of angst and b) academic talented is unequally distributed among individuals in our population and so some students would always be in the bottom 50%/25%/10% of the performance distribution. Neither of those problems were remotely addressable through the school-side solutions that the reform movement was intensely fixated on. Which speaks to another reason why these ideas have held on for so long: in the United States in the 21st century, schools are the proverbial hammer; reformers assume that policy cannot fix families, parenting, or environmental/societal factors and so must believe that school policy changes are the only way forward. In any case, the perhaps-temporary setbacks the school reform movement faced in the 2010s has for the most part done little to erode our national attachment to the Cult of Smart, to the notion that intellectual and academic abilities are the most important in all of human life and correspondingly that we must produce a nation of child geniuses for the sake of social justice.

KIPP’s presence in Goldstein’s piece is particularly noteworthy. KIPP schools are attrition factories and have been subject to accusations of student body-pruning for decades, which of course is the norm rather than the exception in charter schools. (I’ve aggregated a lot of information about just how common admissions fraud is in charter schools before - in many contexts the lotteries that determine admission are run by the schools themselves, an absurd conflict of interest - and you can pull lots of examples, such as when an ACLU investigation found more than 250 schools committing admissions fraud just in California.) Well, KIPP is an example of a notorious “no excuses” institution that’s now maybe sorta kinda willing to think about some excuses, so long as they hide the football sufficiently. Advocating for placing kids into alternative programs rather than college helps maintain a hint of respectability while standing down, however subtly, from one of the most dogged demands of the school reform and charter movements: that every kid end up in college. Perhaps that’s because, as Goldstein sheepishly admits, KIPP graduates only graduate from college within five years at a rate of 40 percent. No amount of saying “no excuses” can obscure the fact that this represents a whole lot of failure at our supposed success factories.

What Goldstein wouldn’t, and can’t, say in the pages of the New York Times should be plain to everyone: that some large percentage of those former KIPP students who never get through college fail to do so because they lack the necessary underlying talent and drive. For decades we’ve slashed standards and spent profligately on remediation, but the fundamental problem remains - some people just aren’t college material, just aren’t built for a life in certain professions that depend heavily on education. This would have been an utterly banal thing to say for most of American history but has become fighting words in the twenty-first century. Well, if you think it’s a harsh thing for me to say, remember that the whole point of my book was to argue that a society that only sees value in one kind of flourishing, that rewards only one kind of human success, is a cruel and impractical one, and a better world is possible.

Yglesias is a good example of someone who appears to have gradually shifted, although only moderately so. In many ways he’s still a conventional neoliberal wonk type when it comes to education, which means that he believes in the power of economic incentives and market forces to engender competition that improves educational equality. You know how I feel about that - a widget-making factory can only make better widgets if the factory has a great deal of control over said widgets, and the proportion of variance in grades and test scores that schools control is around 10% at best. But Yglesias has also been admirably willing to say that the returns from the school reform movement have been paltry compared to the investment and the hype, and he’s much more apt to discuss student talent in a policy context than many of his peers. He recently wrote, “[The bipartisan education reform consensus’s] problems included overpromising on addressing achievement gaps and overreliance on fiddling with teacher pay as One Weird Trick for fixing schools.” Coming from a school reform proponent, you could certainly do a lot worse.

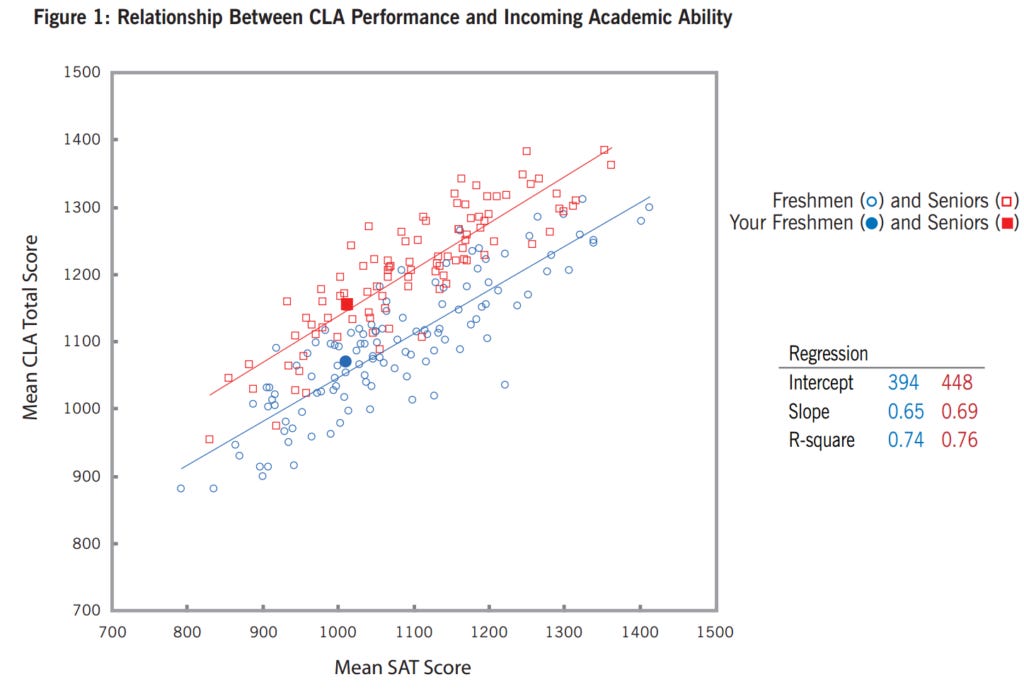

Yglesias also said, in the context of praising that consensus’s overall impact, “The campaign to close achievement gaps failed not because low-income kids and racial minorities didn’t do better, but because everyone was doing better, so gaps persisted.” Which I agree with; indeed, it’s simply a statement of some of the same issues with distributional coherence that I mentioned above, a reformulation of point 2 at the top. I’ve shared this scatterplot a jillion times, not because the data itself is particularly meaningful but because the dynamic is so prevalent in education - the gaps between the blue freshman test averages and the red senior test averages shows that students are learning in absolute terms, but because the schools on the righthand side of the plot improved as much as those on the lefthand side, the less-selective schools could never catch up. This is generalizable, as Yglesias’s observation about the racial achievement gap shows. I just think that this dynamic is more powerful than he seems to understand, and I think you can talk tough about accountability all you want, but it won’t matter if the people you’re getting tough with fundamentally don’t control the relevant variables. But a gradual shift towards understanding that schools cannot close gaps that schools did not create, however partial, is a good development and something I’d like to see more of from our commentators.

Ultimately, Trump is going to want to crush higher ed more than he’s going to want to shake up America’s meritocratic ideals. In many ways, Trump and Devos proved less threatening to public schools than Obama and Duncan, for the simple reason that the former just generally had no philosophy on education at all; Obama and Duncan represented an ideology that I find noxious, while Trump represents nothing but momentary cruelty and whim. Which is why I’m not holding out hope for a German-style education system anytime soon. I actually think that the American higher ed system could be strengthened rather than weakened by a right-sizing effort that saw a single-digit percentage of institutions close, which is already happening to some extent. But the people shepherding that change would have to want to improve our system rather than savage it. Trump doesn’t qualify. So for now, I have to find a little optimism in these rare green shoots of people slowly, maybe kinda sorta coming around to the idea that there will always be good students and bad, that schools can’t force untalented and unmotivated students to become stars, that a school system that sorts good from bad can’t also be an engine of equality, and that a society that has no capacity to recognize various forms of human accomplishment is one that’s doomed to declare many of them losers, no matter what we do in school.

I don’t want to swamp the main argument with more of my usual saw, here, but I think it’s best to understand educational debates as suffering from distributional incoherence. You can skip this if you’ve familiar with my whole shtick on this or if you just don’t want to read hundreds of more words.

A place where I most often get pushback to my philosophy, in Alan’s terms above, is “any pedagogical strategy, practice, or method that improves the performance of the worst students will also improve the performance of the best students”; a lot of people tell me that we could in fact create interventions that would only help the poor performers. I would respond by saying that, first, I don’t even know what that would look like and I’m skeptical such a thing could exist. Intelligence (or academic aptitude or whatever you prefer) is voraciously adaptable; this is precisely what makes it so valuable. To find a method of educating that resists the intellectual assimilation of the most talented students seems… quixotic, I guess, and that’s a euphemistic way to put it. It seems rather perverse, after all, to devote resources to developing pedagogical tools that perform less effectively for some students!

Another common response to my perspective is to say that we shouldn’t care so much about whether students learn things as fast as others or can do them as well as others, that the only thing that matters is whether they can “master the material” - this is the insistence that absolute learning, not relative, is what matters. I might start by pointing out that many students, indeed a majority of students, never “master the material” no matter how much time you give them. Indeed, the truly horrible passing rates in abstract math, even among highly privileged students, demonstrates that failure is always an option. And no matter how much you might want absolute learning to matter most, you will always end up caring about relative learning. The entire notion that education is a tool to increase socioeconomic mobility or equality, to reduce poverty, to close racial gaps in standards of living - all of this depends upon the economic and professional advantages of improved relative performance. People who go to college and put together an impressive resume see economic benefit from doing so because doing so differentiates them from peers.

This is what I mean by distributional incoherence. Most commentators assume that there is such a thing as a distribution of performance in academic tasks and abilities, seeing that as a natural and healthy state of affairs, but are unwilling to countenance the inevitable consequences of a distribution. Consequences such as “Any distribution must have a bottom” and “One person moving up within a distribution of relative performance must necessarily entail someone else moving down.” You can set a goal of equalizing performance so that there is no distribution, if you want to, but we can barely move the distribution we have now and anyway I don’t think you actually want equality. You talk to most anyone who does ed policy and they’ll acknowledge that genuine educational equality is not achievable, and if you press they’ll also admit that educational equality is not desirable. Educational equality would mean the end of academic excellence, as well as a complete collapse in the way that we identify and promote talented people into professions and positions that depend on talented people.

I get some strangled replies to this, which typical involve saying that we should just have average performance and excellence, no bad performance. I’m afraid that you can try to move everyone to the average, but that simply moves the average and now previously-average students are getting Left Behind - and, anyway, we have tried to make poorly-performing students perform as well as average students for decades with little to show for it. You can potentially move the average to the right, ignoring distributional effects and only caring about absolute performance against benchmarks, but it’s performance within the distribution that’s rewarded within the meritocracy and thus is considered loaded from a social justice sense - and, anyway, we have tried to move the average for decades with little to show for it. This is what I mean by distributional incoherence, fundamental failures in thinking about what it means to assess student performance and to make distinctions between those who do better and those who do worse.

"in the United States in the 21st century, schools are the proverbial hammer; reformers assume that policy cannot fix families, parenting, or environmental/societal factors and so must believe that school policy changes are the only way forward."

Until I started reading your stuff on education, the thought that we were asking schools to do too much never really crossed my mind. I used to be very critical of public schools (even though I graduated from public schools) because I thought they just weren't doing their job correctly.

Now I am finally figuring out that our expectation of what any school can do (not just public schools) with a random student is unrealistic, and if we want to try to fix all of these other things, we can't expect to do it through the education system.

Add in point 4. "No, Virginia, there is no magic bullet, no educational practice, no vademecum or cureall, that will make most people or most kids suddenly smarter than average."