Hey guys, tomorrow afternoon in the Book Club section we’ll be discussing “The Open Boat,” Steven Crane’s classic short story. If you aren’t subscribed to the Book Club section this email won’t arrive in your inbox, so click on over there if you want to participate. There’s still plenty of time to read the story beforehand.

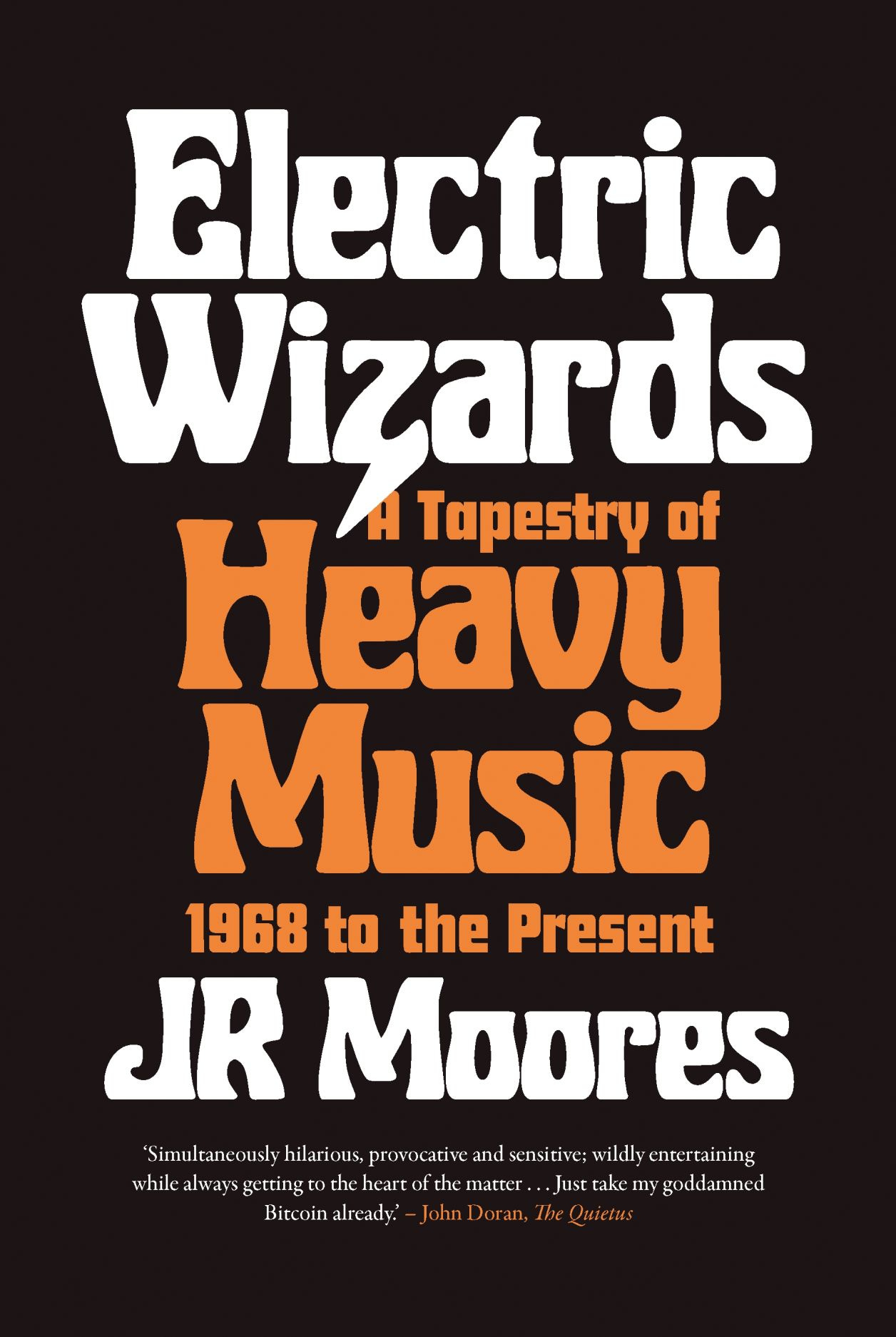

Sometimes, you’re walking through the bookstore, not really feeling anything you see, and then you find a book that feels like it was written just for you. Six months or so ago I was wandering through the basement of the Strand in Manhattan, not feeling inspired by anything I saw, and then suddenly JR Moores’s Electric Wizards: A Tapestry of Heavy Music, 1968 to the Present waved at me. The words “must buy” don’t quite do it justice.

“Heavy music” is key here, and a good choice by Moores, a veteran music journalist from the UK. You might be forgiven for immediately thinking of heavy metal, and indeed that big shaggy genre has been the engine of heaviness in popular music for decades. But as Moores points out, heaviness goes much further than metal. What is heaviness? Moores is wise enough not to include a sentence-long description, though this is unfortunate for us review writers. He rather writes around the concept, using the whole preface to gesture at what he means and doesn’t. Any too-restrictive definition would inevitably constrain what he’s trying to do unnecessarily, although he certainly has strong feelings on what does and does not belong, as do I. He does note that he will primarily be talking about guitar-based music in the book, which is also wise. Crucially, Moores also says “there is little need in who does or does not ‘keep it real.” I absolutely agree with that spirit. It’s always more fun to include than to exclude.

Heavy music is slow, low, and dark. It's lyrical subject matter tends towards the grim and the portentous. It relies on heavy distortion and grinding rhythms to create a sonic style that can be brutal and assaultive. The beauty of it is that each of those attributes can mean a great many different things to different people. For me, a core element is understanding that beloved heavy metal bands like Iron Maiden or Judas Priest aren’t heavy at all in this sense, where a band like Nine Inch Nails certainly is, despite the emphasis on synthesizers in the latter and the skull and bones metal imagery of the former. Iconography has always been integral to heavy music, and I love it (gimme Gwar in their costumes, baby), but fundamentally heaviness is a property of music, not bands.

One very key element of the book is that Moores recognizes that punk is fundamentally unheavy. Punk music has been immensely influential on heavier music, and of course there’s tons of crossover. Some classic punk acts have moments of deep heaviness. (I would say that the first 10 seconds or so of “Anarchy in the UK” is heavy in exactly the way that Moores and I mean.) But punk is defined, among other things, by three elements that are contrary to heaviness: expressly political lyrics, higher-pitched instrumentals and vocals, and speed. And while there are always an immense number of exceptions and exemptions to this stuff, it’s the case that there’s literally nothing heavy about the Ramones and very little heavy about the Clash or Sex Pistols. Metal and punk grew up together, always mutually influencing each other and in conversation with each other, but are very separate impulses. Punk, hardcore, and their various offshoots often access heaviness, but they are not its natural home. This is core to the whole project and the fact that Moores gets it just right is very important, at least to a weirdo like me.

In many ways Electric Wizards is everything I was looking for, a deeply-researched and near-exhaustive chronicle of a lot of music that I love and some I hate, as good of a primer on this broad movement as I can imagine currently exists. He starts with the origin of heaviness in pop music in the Beatles and “Helter Skelter,” which is a little tired and a little cute but not wrong. He then weaves a path through Black Sabbath, the lodestar of the book and the genre, through the major touchstones of heavy metal precursors like Motörhead, through industrial, the hardcore movement, grunge, nü-metal, and more. Along the way, he highlights acts both high-profile and niche, and I learned about several acts that I had never heard of before, which is a thrill. I learned a lot in general - Moores has clearly put in his time in the library, and most of the book is more than adequately sourced. There’s tons of nuggets to be found here, and I got just the combination of big sweeping consideration of trends married to great anecdotes and quotes that I was looking for. Moores also writes well, which really helps along the course of a 423-page book, one that’s meant to be slowly savored.

And also, JR Moores is the normiest normie who ever normied a normie. Moores is very much a Certain Type of Guy, a particular kind of metal fan I’ve known for most of my life, and within that archetype he perfectly fits every stereotype you can think of. He’s a progressive and a hipster, somebody who’s a little embarrassed to love metal (or to be known to love metal), the kind of guy who’s forever telling you “you know if you like these guys, you should be listening to those guys.” His tastes are just eclectic enough, his opinions are just enough steps apart from the perfectly mainstream, his limp social justice politics are just radical enough in the context of genres still dogged by a certain brutish conservatism. (I don’t mind the politics themselves, at all, but rather that Moores is so boring in his presentation of those politics.) This might all seem very arch to you, especially if you don’t have Swans somewhere in your Spotify history. But if you’re like me and you like the music I like I think you’ll know just the Certain Type of Guy I mean, and also be a little tired of Moores’s opinions.

Moores is sure Sabbath is superior to Zeppelin. He hates the Doors, Marilyn Manson, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and hair metal. He’s dismissive of post-Ozzy Sabbath, despite the fact that Ronnie James Dio was the greatest Sabbath singer. He respects AC/DC in a self-defensive way. He idolizes Steve Albini, because of course he does. He regards Britpop as a contrivance of the record labels. Hey, did you know that Alice in Chains is the grunge band that was really heavy? The problem isn’t that these opinions are wrong, but that it’s all so expected, tuned just exactly to the right bearded metal guy dial. I myself am a bearded metal guy, and I like IPAs, but Moores has the taste of someone who only drinks IPAs, you know what I’m saying? I honestly don’t think I was surprised by a single musical opinion Moores expresses, across a book that exceeds 400 pages. It makes the experience less enjoyable for me, even as I’m soaking up so much great history. Surprise me. You’ve got twenty chapters. Surprise me!

Did you know nü-metal… isn't very good? The chapter on nü-metal is titled “The Nadir,” which is about as challenging as a glass of milk. Was the music of that period very bad, in general? Yes, I do agree. But hating nü-metal is so boring, so well-worn, that it makes the chapter an absolute drag to get through. Oh, but did you know Deftones is the good nü-metal band? My lord. If I never hear someone say that Deftones is the good nü-metal band again, it’ll be too soon. “Deftones is the good nü-metal band” is the reflexive qualifier of those who equally reflexively disparage the broader genre. And yes, yes, OK, I like some of their stuff. The point is that if you’re publishing a book in 2021, you have to do something else than write about how nü-metal was bad, how it was the nadir. Yes, JR - we know. You have to tell me more. You have to go further. You have to find a different angle. And so often, he doesn’t.

A weird omission to me is System of a Down. They were always a little to drama club for me, but for many people they were the keepers of the flame of heaviness during “the nadir,” yet they get no mentions in a book on heavy music that has plenty of time to talk about Muddy Waters. And that’s the other big problem: there’s a really weird sense of inclusion and priority. Stuff that would seem patently out of place in the world of heavy music gets long sections while core, popular acts that helped define sounds are sidelined.

It’s a general problem, but two chapters exemplify it. I 100% agree that “Maggot Brain” is a very heavy song, and that the heavy spirit resides in a good deal of P-Funk’s output. But even the album on which that title track resides is mostly not heavy, and the average funk band just isn’t heavy. Yet funk receives its own chapter, and weirder still, so does krautrock. Krautrock! I think a lot of krautrock is very good, but its an existentially not-heavy genre. It seems clear to me that Moores just likes funk and likes krautrock and found a way to awkwardly wedge them into a book about heavy music. But the text loses a lot in discipline and coherence and gains little insight in the trade. Those chapters simply don’t belong in the book, period, end of story; there would have been plenty of opportunities to gesture at those genres in the flow of a chapter about more music more relevant to heaviness. (But do listen to Maggot Brain, if you never have. Its pleasures are many.)

Moores also shows his hand by fixating on minor acts while sidelining bigger relevant players. He talks about micro-niche act Lana del Rabies, bizarrely, for two pages in a book that has so much else to do. Moor Mother receives as much attention as Swans, a band that redefined heaviness for a generation of nerds. Look, I like Moor Mother; you all should check out Moor Mother. But I have no idea what Moores thinks he's accomplishing by going on about how Moor Mother is better than Ministry to conclude his chapter on industrial music. Even if it’s “true,” musical tastes being subjective, it inevitably makes Moores seem like he’s grinding a particular axe instead of understanding his book as fundamentally a work of history. Electric Wizards is a book that clearly wants to stand the test of time, and yet it’s easy to imagine how it could fail to age well, given his preciousness about what gets covered.

This problem makes the book seem positively hermetic at the very end, with its insistent fixation on the still-quite-obscure self-described “precious metal” band Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs. A few other tiny bands are namechecked in those chapters, but the scene they constitute is very small indeed, and it’s a bizarre amount of focus for a decades-spanning book’s final act. It makes me wonder if he didn’t have a previously-published essay on Pigs that he used to fill pages in the book.

Look, it’s inevitable that there are going to be judgment calls when it comes to inclusion and curation. There’s an entire chapter on Melvins, which I think is perfectly appropriate; they’ve done as much as anyone to define guitar-based heavy music and its palette of sounds in the past 30 years. A lot of microgenres spawn from Melvins, and they have been name-checked by dozens of prominent musicians. At the same time, I can’t deny that part of my approval stems simply from my love of that band. If I was, say, someone who came to heavy music through thrash and loved that genre (millions did, thoughI very much didnot), I might not get giving Melvins such a spotlight and paying such short shrift to Megadeth. Metallica appears on maybe 18-20 pages, but the only single album that is considered is Lulu, which seems like deliberate troll shit, and I say that as a Lulu defender. That chapter is immediately followed by another single-band-focused chapter, this one on NapalmDeath. And I think that’s appropriate, more or less, given grindcore’s way of taking metal and hardcore to their greatest extremes. But there’s barely any mention of hair metal at all, and while I would agree that hair metal is existentially unheavy (as well as terrible), a ton of the energy of early metal like Sabbath was eventually pushed into the direction of hair metal, and you just have to do the work of excavating that.

These are all judgment calls, and I don’t think Moores has done a terrible job of picking and choosing. I wish he had been a little more transparent with this process, though. I loved the way he used the underappreciated band TAD as his entryway to talking about grunge. But if you’re writing this book, you just have to write a little bit more about Nirvana and Pearl Jam and Smashing Pumpkins. Even if you don’t think they’re very heavy (and I agree that they aren’t), you have to grapple with the fact that for a huge number of heavy music fans, like me, those bands were the catalyst for journies into heaviness. (How many kids got into Paranoid only after having their minds blown by Nevermind?) The book is about lineages, and the simple fact of the matter is that there will be always be a bigger family tree coming off of Nirvana than off of Wolf Eyes. You have to stay disciplined in your focus to do the job you’ve set out to do.

And I will accept the fact that I am being self-indulgent when I say that the disrespect towards Boris feels incredible to me. Yes, Boris is my favorite band, so I’m biased. But still, they are a massively influential force in heavy music today. You only have to look at their list of collaborators to see that. Moores gives Merzbow his due, which is good, but shouldn’t that prompt him to take a real look at his friends in Boris? Few bands have ever jumped between different heavy genres as fitfully and effectively as Boris, and their almost-total exclusion seems like a real lost opportunity. Alas.

No Pantera? No Bell Witch? Punk isn’t heavy, but riot grrrl is? I would have loved a little digression into lowercase, though I guess that violates the guitar-based directive. And I understand: there’s only so much space in a book. But every weird exclusion makes every weird inclusion look a little bit weirder.

Also, Christ, the relentless return to Sabbath. Holy smokes. Yes, I understand that Sabbath was seminal and influential and I like some (some) of the music. But the obsessive focus on Sabbath not only by Moores but also by many other admirers of metal makes the world of heavy music seem smaller and staler than it really is. I hate sacred cows, especially in music, so when Moores quotes a few musicians as deliberately denying Sabbath’s influence it feels refreshing. There are other bands!

This probably sounds more critical than I mean it. Ultimately, this book does what it says on its cover, beyond my expectations. I was genuinely sad to close it for the last time, as it had become my nighttime ritual to read a chapter before bed and in doing so learn a little music history I didn’t know before. I absolutely recommend this to those who have an interest in the subject, although most of the heavy music fans don’t need my urging and have already ordered it by this point in the review. I wish Moores was a little more logical about what he wanted in the book and didn’t, and I wish he was a little less predictable. Ultimately, though, it was going to take a good-natured bearded British metal hipster to write this kind of immense tome on heavy music, and I am very grateful the book exists. And like Moores I am quite confident that, whatever the trends may be, heavy music will never die.

I know this is deliberately beyond the book's scope, but I'd love a discussion about "heaviness" in music beyond the rock/guitar super-genre.

There's heavy hip-hop, for sure, like some early Wu-Tang and Geto Boys; heavy ambient and space music, like Cryo Chamber; heavy jazz (Charles Mingus has plenty); trad blues is heavy, of course; there's even heavy classical music, like Richard Strauss's "Also Sprach Zarathustra."

I suppose there's some grand unified aesthetic theory of heaviness one could go on about for a few thousand words if one wished, grounding it in the Burkean Sublime or going back to Aristotle's opinions on the emotional effects of musical modes.

One of my pet peeves is crusty old metalheads constantly shitting on nu metal. I've spent my whole life gritting my teeth and ignoring it, but I'm old enough not to care. I've seen the Deftones live at least 5 times, and whole bunch of other acts (Slipknot twice, for example). I say all this as big fan of the bulk of the acts the author references. They'd die before they'd admit it now, but there were racial undertones to the backlash against rap metal, the intrusion of hip hop into an overwhelmingly white music genre.

I always thought there'd come a day when they'd stop complaining about nu metal, but a lot of hair metal guys never forgave grunge either.