Pre-K Research is Mixed, Running to Discouraging, at Best

here's how bad analysis becomes conventional wisdom

At the NYT’s Upshot vertical, Claire Cain Miller says of universal pre-K

The bulk of the research shows that high-quality preschool tends to benefit children into adulthood, especially children from low-income families.

I find this a little brazen. Miller summarizes a corpus of research that even pre-K proponents admit is mixed but finds “the bulk” of the research encouraging. I know it can be annoying to report on controversies rather than to proffer conclusions, but this is a perfect example of when that’s warranted. I read an awful lot of ed research and am pretty plugged in to these arguments, and I’m accustomed to the inevitable “the research is mixed, but…” framing from pre-K advocates. Here, though, you just have a bald statement about the findings of the extant studies, one many in this fight would argue/concede is too rosy. Don’t take my word for it! Let’s take it from various pieces from the liberal thinktank Brookings, selected specifically because their institutional bias cuts in favor of funding pre-K rather than against. From June 2019:

In 2005, the first report about the Head Start Impact Study found that one year of Head Start improved cognitive skills, but the size of the effects was small. While this first report affirmed Head Start’s impact on school readiness, the final HHS report published in 2010 showed that by the end of first grade, the effects mostly faded out. According to the 2012 HHS report on third grade follow-up, by the end of primary school there was no longer a discernible impact of Head Start. Due in part to these reports, some have concluded that while Head Start has some initial impact on kindergarten readiness, the fadeout in impact over early elementary school qualifies attempts to invest more in early childhood education.

From April 2017, summarizing a large task force report:

Convincing evidence on the longer-term impacts of contemporary scaled-up pre-K programs on academic outcomes and school progress is sparse, precluding broad conclusions.

My recent writings and presentations on early childcare have been motivated by what I see as the weak evidence behind the groundswell of advocacy for public investments in statewide universal pre-k.

Unfortunately, supporters of Preschool for All, including some academics who are way out in front of what the evidence says and know it, have turned a blind eye to the mixed and conflicting nature of research findings on the impact of pre-k for four-year-olds. Instead, they highlight positive long term outcomes of two boutique programs from 40-50 years ago that served a couple of hundred children. And they appeal to recent research with serious methodological flaws that purports to demonstrate that district preschool programs in places such as Tulsa and the Abbott districts in New Jersey are effective. Ignored, or explained away, are the results from the National Head Start Impact Study (a large randomized trial), which found no differences in elementary school outcomes between children who had vs. had not attended Head Start as four-year-olds. They also ignore research showing negative impacts on children who receive child care supported through the federal child development block grant program, as well as evidence that the universal pre-k programs in Georgia and Oklahoma, which are closest to what the Obama administration has proposed, have had, at best, only small impacts on later academic achievement.

Again, this is all from Brookings, a liberal think tank that engages in the same genetic denialism they all do and which is rabidly attached to solutionism, the notion that every social problem has some technocratic solution if we just have the will to commit to it. They are convinced that problems like our persistent and large achievement gaps can be solved within the constraints of a more-or-less unmodified capitalist democracy. So if even they are cognizant of the fact that the research record is mixed at best, surely the Upshot can report this faithfully too. Right-wing sources, unsurprisingly, are far more negative.

We could pick out many specific studies that show profoundly discouraging results. Take the Tennessee study, published in 2015, which is one of the largest and highest-quality pre-K studies to date. The nut:

By the end of kindergarten, the control children had caught up to the TN‐VPK children and there were no longer significant differences between them on any achievement measures. The same result was obtained at the end of first grade using both composite achievement measures. In second grade, however, the groups began to diverge with the TN‐VPK children scoring lower than the control children on most of the measures.... In terms of behavioral effects, in the spring the first grade teachers reversed the fall kindergarten teacher ratings. First grade teachers rated the TN‐ VPK children as less well prepared for school, having poorer work skills in the classrooms, and feeling more negative about school.

I have previously shared Duncan and Magnuson 2013 in this space, which shows that as time went on major Head Start/pre-K studies got more and more pessimistic, likely because we were getting better at doing studies as the decades passed. There’s an awful lot of want-to at play here, a profound optimism bias in education research funding which pushes many in academia and thinktanks to relentlessly pursue encouraging findings in a way that inevitably influences results. You often find strained readings of the available evidence to support the predetermined outcome that pre-K provides the kind of educational benefits to make it “worth it.” Anyone who wants to engage on this topic fruitfully and honestly, whether a proponent or skeptic, has to factor in the intense pressure within policy circles to find evidence of pre-K’s efficacy. Too many people have too much invested in pre-K, socially and politically and even financially, to simply accept the discouraging news from the research record. As always, educational policy involves a lot of looking where the light is.

Do I think it’s inherently illegitimate to read the available research as positive towards pre-K? No, you can proffer more optimistic readings than I do and still speak responsibly. But any such conclusion would have to come with heaps of qualification, the Upshot has provided almost none, and I would contend that the article requires a formal correction for that reason. (I doubt they’d agree!)

There are a many reasons why pre-K might not work1, but the most parsimonious is that academic ability, both in terms of raw cognitive processing and non-cognitive skills that enable academic flourishing, is heavily influenced by genes. And the tendency for fadeout is highly compatible with the Wilson effect, which shows that as children age the degree to which various cognitive and behavioral metrics are influenced by genetic heritage increases. The point is not that environment doesn’t matter. The point is that a) the so-called “shared environment,” the behavioral genetics term that more or less refers to the family and parenting effects but also can refer to school effects, has consistently shown little influence on outcomes by adulthood; b) the so-called “unshared environment,” which more or less refers to all of the random things that influence a person that we can’t quantify, controls more; and c) there are likely ceiling effects at play here - that is, yes, moving a child from true neglect to a nurturing and supportive learning environment could have major positive effects, but once children enjoy a basic minimal level of safety and comfort the returns from improved environments likely diminish.

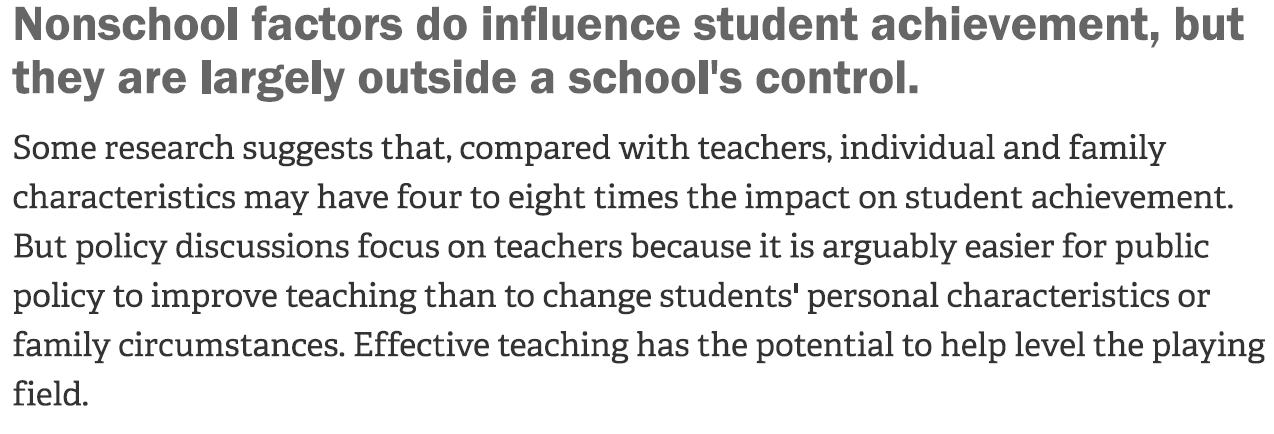

Indeed, I am on record as saying that I don’t think there’s really such a thing as school quality, and that while teacher quality may be a real and meaningful variable it is likely confounded to hell and there may be interaction effects2. That’s not the focus of this post and I won’t belabor the point here, but it’s worth mentioning. (My big picture summary of education research here remains maybe the most important thing I’ve published here, so check it out if you haven’t.) Before Jon Chait materializes like a poltergeist to complain, here’s the Rand Corporation’s education arm - very much a neoliberal pro-reform chop shop - summarizing how the variance breaks down:

When I found this while researching my book, I laughed out loud: “this isn’t actually the problem, but this is where we can imagine doing policy interventions” isn’t very encouraging. But it’s useful that this idea is floating around out there, that student-side factors are more powerful determinants of outcomes than school-side. If our educational policy debates are ever to bear fruit, we have to start there, with people on all sides getting real about the fact that student-side factors dominate school-side factors in ascribing observed variance. And yet Miller summarizes the research in a way that suggests to the lay reader that we can says that pre-K works with some confidence. I think this violates the basic commitment to giving readers a responsible view of the current state of knowledge.

I don’t want this post to sprawl to much, but I could certainly go on about this general topic. From the Upshot piece:

The bill in Congress includes quality thresholds. It says that within six years, all children should be able to secure a spot in a center of the highest quality.

It’s politics, so it’s par for the course, but it’s worth saying this anyway: this is nonsensical. Quality, if the term means anything at all, exists along a spectrum. It will always be unevenly distributed. To say you’re going to mandate “the highest quality” across a vast number of institutions and personnel, in any domain, is Lake Woebegone shit, just total defiance of basic understanding of how institutions work. One thing that you can never ensure, in any context, is universal excellence, and if educational equality (whatever that might mean) depends on it then we’re chasing a ghost. In the past I’ve called this attitude “we’ll only scale up the good ones” and I would hope anyone who’s been part of any human institution, public or private, understands what a mistake it is to hang your hopes on scaling excellence up across millions of students and teachers.

None of which means that I’m opposed to our government joining with so many other industrialized nations and providing some form of childcare for children younger than the age of 6. But that’s how it should be framed, as childcare. The most noble purpose of funding pre-K is keeping kids alive and giving parents the opportunity to work during the day without spending all their earnings on childcare. As with afterschool programs, the trouble with predicating childcare on the idea that it raises test scores is that usually test scores don’t rise, and where are you then? Instead, we should advocate for childcare as such, establishing programs that put it in reach of more working parents, and defend it on those terms. Manipulating the research record to support a tendentious conclusion about the efficacy of pre-K, in the long run, can only hurt our efforts. Advocate for universal childcare and if we can secure durable educational benefits, all the better. But don’t lead with weakness rather than strength.

Work how? Work to improve quantitative educational metrics and the kind of “soft skills” frequently studied in ed research. Research showing a large positive effect for children’s health was plagued by huge attrition problems.

By this I mean that it seems very intuitively likely to me that, rather there being some uncomplicated spectrum of good teachers or bad, some teachers likely suit some students/types of students better and some worse, which would complicate assessing quality beyond the point at which it would be practically useful.

No less a hardass than Charles Murray pointed out that preschool would be a great way to help poor kids stay in a warm, safe, place and should be funded on that basis. Or, as I put it:

"Maybe we’d stop holding preschool responsible for long-term academic outcomes and ask instead how it helps poor kids with unstable home environments and parents with varying degrees of competency, convincing these kids that their country and community cares about them and wants them to be safe."

https://educationrealist.wordpress.com/2013/04/05/philip-dick-preschool-and-schrodingers-cat/

My kid attends a pricey Montessori preschool. We just received his first progress report, and it’s 17 pages. They are tracking so many things. For example, he has improved in the area of “plant polishing.” I didn’t even know you were supposed to polish plants.

I am willing to believe pre-K makes no difference in longterm education outcomes. Most research that claims effects is plagued by selection bias, and the few with random assignment aren’t promising. But I do find value in the experience he’s having this year, just as a 4-year-old, verses what he’d be doing in daycare. They’re paying so much attention to his development, working with him on social skills (key for an only child) and providing a huge variety of indoor and outdoor activities for him to explore. Plus there is a ton of communication with parents on how he’s doing.

It has value beyond the impact on his future grades, or his future anything. I’m glad he’s having a good experience this year because that matters to me all by itself. So I’ll never say that we shouldn’t bother with pre-K just because it doesn’t improve future scores. (Not that Freddie is saying that.) I’m glad it exists.

Ideally, all parents should have the option of preschool or daycare, and both should be free.

It’s frustrating that we need to claim effects on future test scores to justify funding for families, because all of the false or inflated claims just lead us further into fantasyland where school solves social and economic problems.

Anyway, it looks like the pre-K funding in BBB had been gutted (source: Matt Bruenig’s Twitter). Same with childcare funding. So not much will change.