Would you believe that when I sit down to write these little capsules of what I wrote in the past week, I can never remember what I actually wrote? Just no idea.

This Week’s Posts

Monday, 5/17/201 - You Aren’t Actually Mad at the SATS

As the University of California moves to drop the SAT and ACT, I debunk some myths about the tests - they don’t predict college success (they do), they only measure one’s ability to take a test (they don’t), they are merely a reflection of socioeconomic status (they aren’t), they are easily manipulable with coaching/tutoring (they aren’t). It’s a topic on which liberals long ago decided they can just make shit up, which I find frustrating. The larger point is that these tests are uncomfortable for progressive people because they reveal a true but unpleasant reality of human life: we are not all equal in our abilities, most certainly including academic ability.

Of course the elephant in the room here is race. I support race-based affirmative action, but the current system we have now is, at least at private universities, a farce. (There is considerable evidence that the large majority of those diversity slots are going to affluent students of color, particularly international students, rather than the economically disadvantaged Black and Hispanic students liberals think they’re helping.) But the larger point is this: liberals refuse to confront the possibility that the tests are giving lower scores to Black and Hispanic students because those students actually are less prepared than students of other races. Despite what they say, this is true even controlling for income band. For example, on the SAT Math Asian students from the bottom income quintile outperform Black students from the top income quintile. The Black-white gap, with income band controlled, shows similar dimensions. The reasons for this are complex, obviously, and the argument that this discrepancy is an indicator of larger societal injustice makes itself. But the SAT data is confirmed by GPA data and state-level standardized testing results as well. Recognizing that Black and Hispanic students are not as prepared as their white and Asian counterparts is not taking part in a racist conspiracy. It’s taking the wellbeing of Black and Hispanic students seriously. Because we know what happens to this underprepared students when they arrive at college: they take on student loan debt, struggle, and drop out at vastly higher rates. Does that sound like humane policy to you?

Besides, the small-but-real correlation between SAT scores and SES is not a problem to be solved because lower SES students are genuinely less academically prepared than higher. This should be common sense, and it too is confirmed by GPA and related data. The SAT is correctly measuring the construct it is designed to measure; it’s just that the outcome - rich kids genuinely are better at school than poor - is something progressive people don’t want to countenance. (This is especially true if we acknowledge a likely explanatory mechanism, that smarter people both make more money and have smarter kids, both of which are supported by a great deal of empirical evidence but which require confronting the genetics of individual differences.) And the problem here is the same as with race: I am in general sympathetic to the call for income-based affirmative action, but the devil is in the details, and if we just throw these less-prepared poorer kids into the deep end without investing the considerable amounts of time and money it will take to support them, we’re engaged in cruelty in the guise of equity.

The SAT doesn’t make our education system unequal. It merely reveals the inequality that already exists. Getting rid of the tests that show us the uncomfortable reality of our system is so wrongheaded and pointless. So of course the practice will spread.

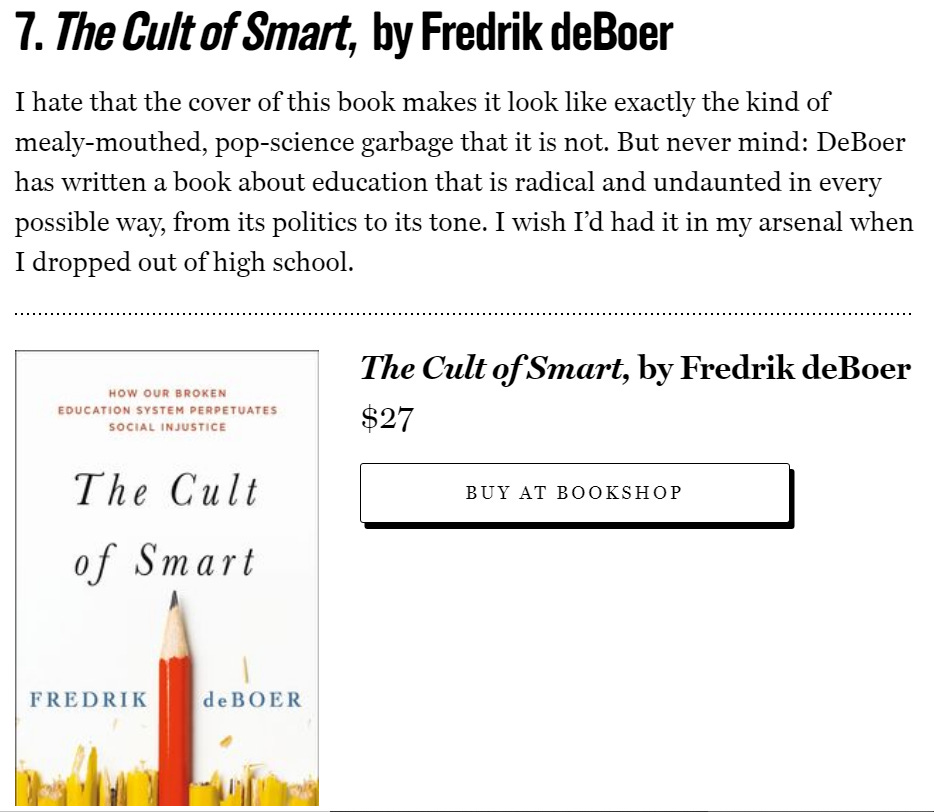

Tuesday, 5/18/2021 - by request: The Cult of Smart

A little rundown of the arguments in my book, which conveniently doubles as a concise diagnosis of what I think is wrong with meritocracy and our current economic and educational moment. Incidentally I recently learned that 98% of the books published in 2020 sold less than 5,000 copies. That makes me feel a little better. Kinda.

This helped a lot too.

Wednesday, 5/19/2021 - the Age of Kayfabe

A reflection on a strange political moment which seems, for progressives, to require a constant mutual commitment to unreality, a shared fantasy about the immediate outlook for truly radical reforms and a refusal to recognize that our discourse norms and argumentative spaces have become deeply toxic. I consider “Defund the Police,” a topic with some noble intent and a whole lot of confusion, terrible messaging, and ultimate political uselessness. I lament.

Friday, 5/21/2021 - Other People’s Lives (subscriber only)

For my subscribers this week, a meditation on a pervasive sense of meaninglessness and a constant anxiety among affluent people, which I chalk up to a lack of structures that provide guidance about how to live. In particular, I argue that many these days feel affronted by choices made by others, as these choices imply a different way of living than the way we live ourselves. I note the poverty of trying to build a self around the things you like. And I argue that this anxiety about other people’s lives is corrosive to the basic notion of pluralism, the ideal of society where we all live our own versions of the best life, which will always be different from those of our neighbors.

From the Archives

I recommend this piece on the Gambler’s Fallacy, which is the phenomenon of assuming periodicity where none should be implied. That is, people often think that because there has been a seemingly-unusual run of one outcome, the alternate outcomes must become more likely by that very condition. As I say in the piece, the classic example of this is seeing a run of one color on a roulette table and thinking that it must therefore be more likely to hit the other color. In fact the odds are exactly the same; reality does not “remember” the outcome of chancy events.

The piece was in large part a product of frustration with public response to the linked Kathryn Schulz article, which received immense fanfare in the rest of the media and on social media, in large measure because of people applying the Gambler’s Fallacy: the notion, repeated again and again following the article’s publication, that the Pacific Northwest is “overdue” for a massive earthquake. But this simply is not supportable given the definition of a recurrence interval. Of course no correction of that misunderstanding ever came, Schulz’s follow up where she discussed this misinterpretation got minimal attention, and due to the nature of geological time, nobody will ever notice that the communal response to the essay was so irresponsible. But I’m shouting into the wind.

Incidentally I think some will find it ironic that I objected (in 2017) to how the risk of a global pandemic was being represented, but I find that everything I said there holds up. There is a lot of the Gambler’s Fallacy going on when people predict things like epidemics, and the conditions of epidemiology really have changed. I did probably underestimate the negative impacts of a more globalized world, but a pandemic wasn’t “due” because we had not had one for a long time. And incidentally I think it’s fair to say that, from the perspective of history, Covid-19 has in fact been remarkably well-contained given underlying conditions of the disease and its spread, thanks to modern medicine. Also I pointed out that the biggest health threats remain smoking, heart disease, and obesity, and indeed twice as many people died from heart disease in the United States in 2020 as from Covid-19. Anyway, check it out.

Song of the Week

Me too.

Substack of the Week

In my last year as a Twitter user (or, as I like to call it, the Dark Time) I got in a minor bit of trouble with some lefties there because I had casually mentioned that I sometimes email Razib Khan for questions about genetics. I read a lot about the topic and try my best to stay abreast of some of the developments, but a great deal of the science is simply beyond me, so I often will ask for help from people who know a lot. Razib, it’s fair to say, knows a lot. But Razib has also been canceled; in 2015 he got hired and quickly un-hired by the NYT, thanks to having been published in far-right places like Taki Mag and VDARE. (Which, for the record, are gross.) So I got a little residual blowback for admitting that I occasionally went to him for information about subjects on which he is vastly more informed than I am.

Which is strange. I wasn’t asking him about pseudoscientific racism, which he was kind-of-but-not-really accused of by Gawker. I was asking him about population genetics and the way that traits are dispersed throughout large populations over time, and I said so to my critics on Twitter at the time. But suppose I was asking him about race science: so what? I don’t know what he actually thinks about that topic, as I have not seen him write directly about it and the accusation against him was driven by innuendo. But say he holds with the Steve Sailer version of the world. Why would listening to what he had to say mean that I had to believe it, that I would come to accept it, that I endorsed it? The idea that we’re all so vulnerable to bad ideas, endlessly moldable clay that can become one of the fallen if the wrong idea briefly flits across our brain, is so bizarre and pernicious. Where did this trope come from?

This is, for me, a really basic intellectual and ethical commitment: reading someone does not imply endorsing anything about them, including the specific thing you’re reading. I hate to bring this back to the David Foster Wallace discussion, but it’s a perfect example; the notion that seeing someone on the subway reading a DFW book tells you something about that person’s soul is ridiculous, because it doesn’t even tell you that they like David Foster Wallace. Who is behind this bizarre idea that the only reason you might read something is because you want to associate yourself with it or its argument? I recently finished reading a book by Mark Lilla; I assure you, I did not read it because I like Mark Lilla. The basic assumptions here just reflect such an impoverished vision of the life of the mind, where the thought of reading anything that you disagree with is simply assumed away, where you know before going in how you will feel about every written argument you encounter, and where we’re all such incredibly manipulable creatures that if we encounter hateful rhetoric we will immediately become captured by it. If you are that susceptible to every ugly idea that crosses your path, that’s a you problem.

It’s all a little irrelevant in this case anyway, as Razib’s Substack doesn’t actually contain much I disagree with. It would be hard for me to disagree anyway: I don’t know much about the steppe, and studying the flow of human populations over time with genomics is pretty baffling to me. I read David Reich’s book and could barely follow it most of the time. (I wouldn’t say that this was about technical details of DNA, though. It’s more about basic conceptual difficulties in imagining how populations move across the globe and change over time.) So I go to Razib’s blog to learn. What I like is precisely that it’s not really a blog about genetics; there’s a ton of history here that is integrated seamlessly into the discussion of genomics, with a lot of contrarian takes on the way ancient populations formed and how they led to the modern world. It’s worth reading and supporting, if you can live in a world where you might come in contact with ideas that are not approved by the liberal Politburo. Let’s fight for a world where we are defined by our values, not through guilt-by-association.

Book Recommendation

Widow Basquiat: A Love Story, Jennifer Clement, 2000

I have a complicated relationship to the romanticism of “old New York.” My father lived here in the 1970s, as did my godfather, and stories that I’ve heard from them really indicate the casual brutality of the place. My godfather Flip tells of being mugged by someone who took not just his wallet and watch but his belt and shoes. Another time a mugger took his wallet, started to walk away, then thought better of it and turned back around so that he could grab my godfather’s glasses and break them in half. Just for the pleasure of doing it, I suppose. Worse, my siblings and I came very close to blinking out of existence once, as my father was stabbed just below his heart by somebody who was out of his mind on drugs; two inches higher and I never would have existed. Sadly for the stabber my father had a glass liquor bottle with him and, when the guy lunged in to stab him, hit him right in the back of the head with the bottle, by pure instinct. Apparently the guy suffered serious and permanent brain damage, a fact my father regretted for the rest of his days.

I also got to experience a little of it myself as a child, as we would visit New York often to see his old friends. And it was big and overwhelming and great, but also deeply unpleasant in many ways. The subways were an absolute mess and you could feel the menace of crime when you rode them; I know that’s not a cool thing to say in this era where all good progressive people are supposed to shrug at crime, but it was true. There’s an awful lot of trash in the streets now but it was even worse then. People walked with their eyes down at night, hustling along quickly in fear of being on streets where there legitimately was great danger of being the victim of violence. Prospect Park, now so associated with bourgie Brooklyn, was so dangerous people wouldn’t cut across it in the day. Also, the dog shit. The amount of dog shit on the streets in New York City in the 80s and 90s…. If you never experienced it you have no idea. It was everywhere. You couldn’t walk down the street! Every fiber of my being wants to reject everything Rudy Giuliani ever did, but the crackdown on people just letting their dogs leave physical waste everywhere was an unalloyed good. As others have often said, people who now idealize the New York of this period are usually those who didn’t experience it.

And yet. Both my my father and my godfather adored the city and looked back fondly on that time. Flip never left. They had other stories too, and they told of wild and libertine times with amazing people experiencing genuine diversity of a type never portrayed in mawkish advertisements from virtue-signaling corporations. And it is absolutely true that there simply could not have been that explosion of art and music in those decades if the rents had not been so cheap, and a safer and less dirty city would have been a more expensive city. Few artists were more defined by this period of cheap lofts, moral licentiousness, and artistic ferment than Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Widow Basquiat tells the story of Suzanne Mallouk, the woman with (as the title implies) the most claim to being Basquiat’s life partner. As the title also implies, this is a story of a man told through the perspective of a woman, in turn telling it to another woman, and yet this refracted sense actually strengthens the book. And there is yet another layer, as even Basquiat himself is mostly a lens through which to grasp that old New York, when Soho was cheap living, when artists could scrape enough together to live and work in giant lofts, when punk bands formed as a way to pass the time and then became iconic. (And when cops committed acts of violence with impunity, which, well.) There’s just so much color here, and while it’s undoubtedly a love letter to an imperfect time, it’s also a mature look at the costs of artistic freedom, the pain of watching someone who loved you get famous, and the slow dissolution of heroin addiction. If that all necessarily comes packaged with some romanticism, well, who could complain?

A little romance never hurt anybody.

Comment of the Week

I think 'the poptimists won' is accurate, but what did they even win? Rolling Stone and Spin are brands that are on life support, Pitchfork is a website the vast majority of Americans have never heard of. The only time I hear people cite reviews in any context these days is 'It got a 90% on Rotten Tomatoes'. Marvel movies took over Hollywood because Chinese audiences like them, not because anyone cares what the NYT critics think. The internet killed the power of taste makers by crushing their institutions and making it free and easy to publish your opinion widely. That was the more important shift to poptimism, less a cultural trend, more a structural change tied to technology. Increasingly the taste makers are algorithms, I get most of my new music recommendations via Spotify now, a bit soulless but it works - EBS

That’s it for this week! Check back next week, where I write something controversial but cool, exasperating but beautifully expressed. Enjoy your Sunday.

You probably already know that Matthew Yglesias had a post on slow boring regarding the SAT yesterday. He linked to your post and cited one of the studies you linked to. But there was a comment posted by one of the subscribers that I thought would interest you. The commenter is one of the few right-of-center commenters on Slow Boring and here’s what he had to say about your book:

“Freddie DeBoer's book and the heritability of intelligence (as measured by SAT & academic achievement) are the primary reasons I changed my mind and now support welfare policies and a progressive tax code. I was raised in a household that valued hard work, and implicitly equated success in any field of endeavor to the level of dedication and effort put forth. I am grateful for the work ethic that upbringing instilled in me. I still think personal responsibility, effort, courtesy and risk-taking are important differentiators in levels of success and those things should be rewarded.

The research into the heritability of intelligence, though, is rock solid. It makes us uncomfortable when stratified by race, but that doesn't invalidate the data. And once I internalized the conclusion that a part (even a large part) of one's success in our meritocratic society is inherited, I finally recognized that those who earn less money are also victims of those same phenomena. Though we can and should argue over how much of one's earnings are deserved due to self-controlled actions versus the luck of birth (parents, the society created by our forefathers, etc), the redistribution of some portion of those earnings from the lucky to the unlucky is now something I strongly support.

The level of redistribution, and mitigating the moral hazard of that redistribution, is where I wish our political arguments would take place. The centrality of Kendi-style, identity-based arguments in today's political discourse is frustrating to me.”

So maybe your book was not the pop-seller you were hoping for (though time will tell. I could see your book getting a steady, slow following and becoming more popular than you see now). But you genuinely changed someone’s mind. We know how rare that is these days. And that will have a ripple effect. And knowing your ultimate goal of compassionate redistribution of wealth, I call that success.

"The idea that we’re all so vulnerable to bad ideas, endlessly moldable clay that can become one of the fallen if the wrong idea briefly flits across our brain, is so bizarre and pernicious. Where did this trope come from?"

That's not what it is. At least not in this case. The reason for cancelation and censorship isn't that the ideas are bad. It's that they are in a lot of cases completely reasonable and that it's the liberal consensus that's wrong, and that if you expose people to them they might believe their lying eyes.

Was the possibility - not the guarantee, the possibility - of a lab leak of COVID a "bad idea"? No, it was a very, very reasonable one, hence the screaming denunciation and banning of anyone who mentioned it for the better part of 18 months.

Nobody gets canceled for saying that high crime is caused by the fact that the moon is made of green cheese, even though it's a worse idea that most any competing theory.