Let’s start by conceding that what I don’t know about artificial intelligence could fill a vast ocean.

Like many people, I am by turns impressed and unimpressed by ChatGPT, the recently-unveiled AI chatbot. Its results are generally coherent and polished, which is impressive - impressive enough that Microsoft appears to have invested $10 billion in its developer. And yet it also returns responses that are generally flavorless and generic, and sometimes wrong. It’s an uncanny simulator for freshman composition essays, but the world is hardly lacking for those. I mentioned this past weekend that, often, when asked to produce stories about specific characters or settings, or to parody or ape the style of a particular writer, the results appear to have no particular relationship to those characters or settings or writers - they’re pro forma and without defining character.

I imagine that those results can be improved over time. But I think it’s important that everyone understand what this kind of AI is and is not doing. Let’s pick one particular issue for AI that must parse natural language: the dilemma put forth by Terry Winograd, professor of computer science at Stanford. (I first read about this in this excellent piece of AI skepticism by Peter Kassan.) Winograd proposed two sentences:

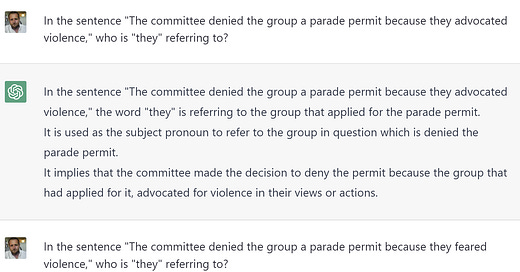

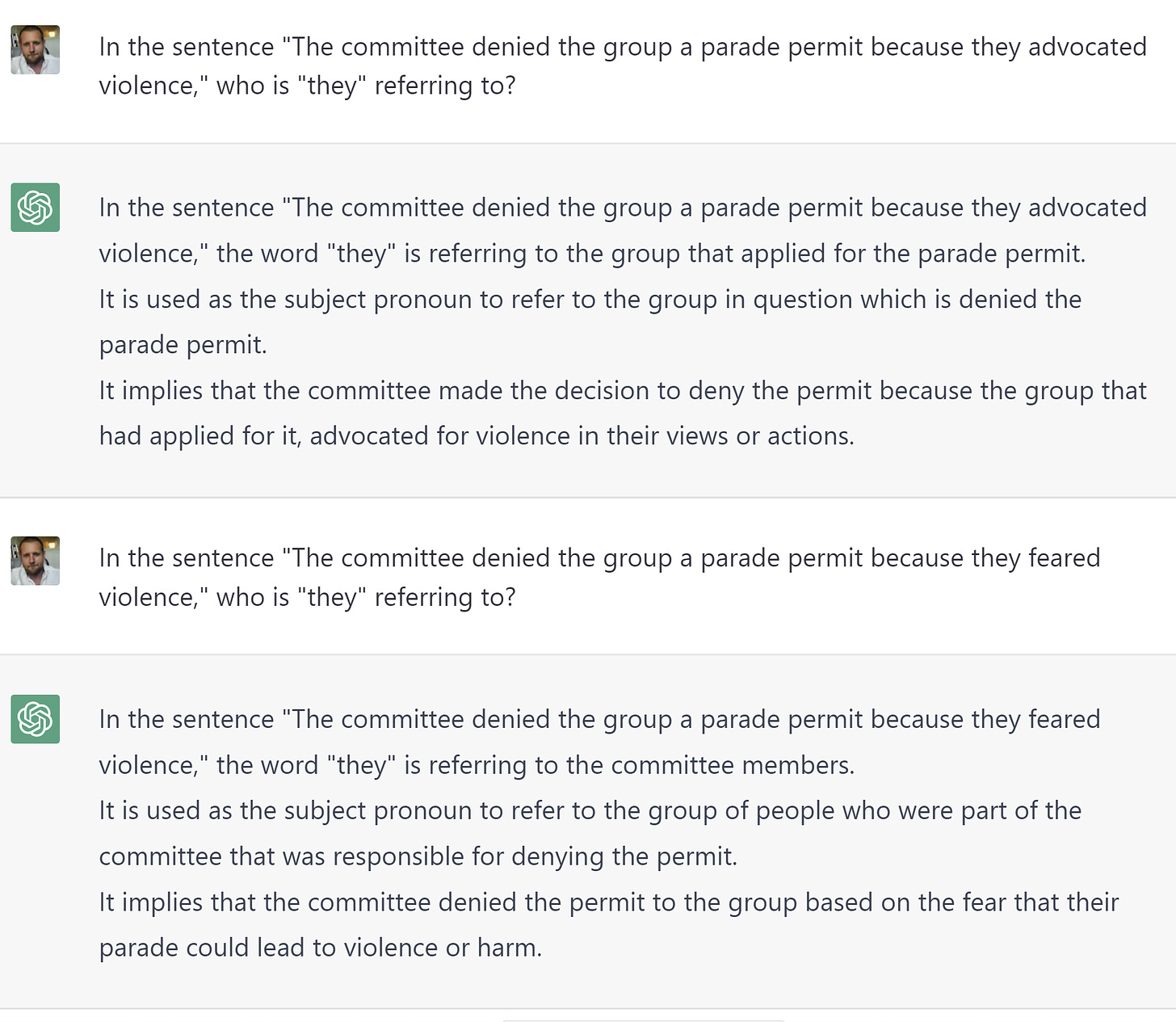

The committee denied the group a parade permit because they advocated violence.

The committee denied the group a parade permit because they feared violence.

There’s one essential step to decoding these sentences that’s more important than any other step: deciding what the “they” refers to. (In linguistics, they call this coindexing.) There are two potential within-sentence nouns that the pronoun could refer to, “the committee” and “the group.” These sentences are structurally identical, and the two verbs are grammatically as similar as they can be. The only difference between them is the semantic meaning. And semantics is a different field from syntax, right? After all, Noam Chomsky teaches us that a sentence’s grammaticality is independent of its meaning. That’s why “colorless green ideas sleep furiously” is nonsensical but grammatical, while “gave Bob apples I two” is ungrammatical and yet fairly easily understood.

But there’s a problem here: the coindexing is different depending on the verb. In the first sentence, a vast majority of people will say that “they” refers to “the group.” In the second sentence, a vast majority of people will say that “they” refers to “the committee.” Why? Because of what we know about committees and parades and permitting in the real world. Because of semantics. A syntactician of the old school will simply say “the sentence is ambiguous.” But for the vast majority of native English speakers, the coindexing is not ambiguous. In fact, for most people it’s trivially obvious. And in order for a computer to truly understand language, it has to have an equal amount of certainty about the coindexing as your average human speaker. In order for that to happen, it has to have knowledge about committees and protest groups and the roles they play. A truly human-like AI has to have a theory of the world, and that theory of the world has to not only include understanding of committees and permits and parades, but apples and honor and schadenfreude and love and ambiguity and paradox….

Well -

You could say that ChatGPT has passed Winograd’s test with flying colors. And for many practical purposes you can leave it there. But it’s really important that we all understand that ChatGPT is not basing its coindexing on a theory of the world, on a set of understandings about the understandings and the ability to reason from those principles to a given conclusion. There is no place where a theory of the world “resides” for ChatGPT, the way our brains contain theories of the world. ChatGPT’s output is fundamentally a matter of association - an impossibly complicated matrix of associations, true, but more like Google Translate than like a language-using human. If you don’t trust me on this topic (and why would you), you can hear more about this from an expert on this recent podcast with Ezra Klein.

You don’t have to take his word for it either, though. Indeed, just ask ChatGPT.

There’s this old bromide about AI, which I’m probably butchering, that goes something like this: if you’re designing a submarine, you wouldn’t try to make it function exactly like a dolphin. In other words, the idea that artificial intelligence must be human-like is an unhelpful orthodoxy, and we should expect artificial general intelligence to function differently from the human brain. I’ve never been particularly impressed by this defense. For one thing, for many years human-like artificial intelligence has been an important goal; simply declaring that the human-like requirement is unimportant seems like an acknowledgment of defeat to me. What’s more, dolphins have a lot of advantages on submarines - they’re slower in straight lines but quicker to turn, nimbler, more adaptable. And dolphins don’t need human pilots. Besides, you’d like to know how dolphins swim simply from a scientific perspective, wouldn’t you? Failures in AI always occur against the backdrop of a larger failure: we still know so little about cognitive science and neurology. You can’t replicate what you don’t understand.

I won’t try to summarize Douglas Hofstadter’s entire career here. I’ll just say that ChatGPT seems to me to be an advance, but an advance in the status quo: the AI tools that are not human-like get more and more sophisticated, but the work of creating a machine that thinks the way a human thinks remains in its infancy.

Update: Since this has been controversial in the comments, again, let’s ask the AI itself:

Also, this profile of Douglas Hofstadter is a decade old, but it’s a good introduction to the fundamental conceptual issues (as opposed to technical difficulties) at play with human-like AI.

ChatGPT can pass the canonical Winograd schema because it has heard the answer before. If you do a novel one, it fails. Someone posted a new one on Mastodon "The ball broke the table because it was made of steel/Styrofoam." In my test just now, it chooses ball both times.

You can reliably make chat gpt fail the winograd test. The trick us to split up the clauses into different sentences or paragraphes. Eg:

Person 1 has attributes A, B, and C. (More info on person 1).

Person 2 has attributes D, E, F. (More info on person 2).

Person 1 wouldn’t (transitive verb) person 2 because they were (synonym for attribute associated with person 1/2).

Chat GPT doesn’t understand, so it uses statistical regularities to disambiguate. It over indexes on person 1, because that’s the more common construction. Sometimes it can pattern match on synonyms, because language models do have a concept of synonymy. But you can definitely fool it in ways you couldn’t fool a person.