What (Some) College Administrators Understand That (A Lot of) Wonks Don't

the answer is always selection effects

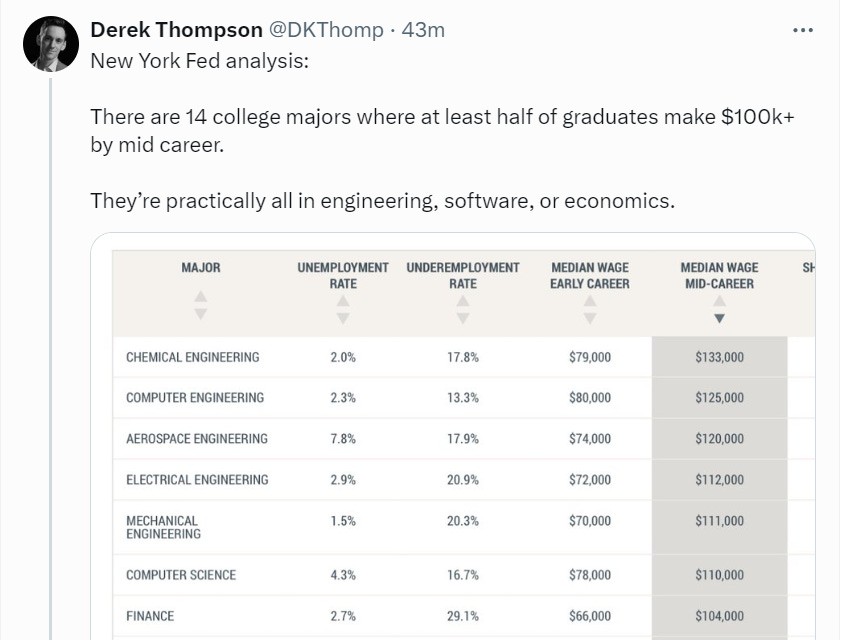

If you’ve been reading me for any length of time at all, you already now how I feel about these tweets from Derek Thompson of The Atlantic. This outcome information is only useful to students if they can be confident that they actually can a) get into those fields and b) avoid the lowest rungs of their labor conditions. And we can’t say that based on outcomes because of selection effects - the students with the essential cognitive skills (however defined) self-select into the majors that result in these good careers and the kids who lack those essential cognitive skills are screened out of those majors, and thus we’ve got a big glaring confound here.

IQ is probably a decent but not-great predictor; traditionally IQ effects on income are modest. But there are non-IQ cognitive strengths that influence outcomes too, and of course preference is an important factor that people can’t just choose - as Thompson’s second tweet suggests, a lot of people pursue less tangible professional goods than pure income, and it would be a mistake to suggest that they can just override those preferences and pursue money at all cost. (Some profoundly talented people are very happy to be starving artists, and I’ve known my fair share.) So while there’s a natural ceiling on how well a measure like IQ can correlate with income, that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a big cognitive screen standing in between a lot of marginal students and the economic rewards show in this chart. And if you restricted yourself to the top percentiles of job desirability and gave all of Google or Apple’s engineers various tests of general cognitive aptitude, I think you’d find very strong performance indeed.

“These majors get great financial outcomes, so we should push more and more students into them” is very understandable reasoning but misguided. Setting aside the implausibility of having an all-engineering, coding, or finance labor economy…. I have a big network of people who work at colleges that I interact with regularly, and I think this is something that frustrates them. Commentators often ask why colleges don’t do more to push students into the fields where the jobs and money are. Tell more kids they should go into engineering! But people who do the advising in colleges have perspective on this question that others lack: they have to help pick up the pieces when students start majors they’re not equipped for in terms of talent and temperament. If a pundit says that everyone should go into computer science, there’s no stakes for them. When someone providing formal professional advising to a student tells them to go into computer science, only for that student to find (as so many do) that they can’t match the rigor of that discipline, that advisor has to deal with the back end as the student chooses a new major and tries to cobble together the credits to complete it, which takes time and money. And if you think that’s unfortunate, remember that it’s still more humane than graduating someone into a field where they can’t excel.

Thompson says that this sort of thing should be more widely known. But I think it is known, by college students and colleges alike. The trouble is that knowing which fields enjoy high salaries and being able to secure the positions that earn those salaries are two very different things. Here’s another place where an analogy to athletics is useful. Major league baseball players make astounding amounts of money, even relative to professional athletes as a whole. And yet nobody says “go where the money is, get a job as a left fielder on the Diamondbacks!” Nobody says that because everyone knows that it would be a pointless and cruel thing to say, and it would be a pointless and cruel thing to say because we have a built-in understanding that careers in sports track talent and that athletic talent is an unequally-distributed resource. In an ideal world, you’d have a similar situation with engineering or computer science or similar. The reality is that, for one thing, sports provides an unusual amount of objective performance data to tell us who’s good enough and who isn’t. For another, we have a political prohibition in our society against acknowledging that cognitive talent is also unequally-distributed, that different students from the same countries, the same fields, the same colleges, even the same families often have widely-diverging levels of baseline talent. So while you can choose your own major, we quietly understand that doing so won’t change the fact that someday someone with power may evaluate your talent and say you aren’t good enough.

I’ve often referenced Purdue’s notoriously challenging First Year Engineering program, which I got a close-up look at when I was teaching freshman there during my PhD studies. It’s a classic “weed out” program, designed to introduce the rigor of engineering early on in a student’s prospective career; the instructors are often very frank with students that their goal is to separate the people who will make it from those who won’t. Every time I talk about it, some commenters get mad. “That’s so cruel!” they say. “They’re squashing the dreams of those kids!” But of course the whole point is that it’s the alternative that’s cruel, letting students who aren’t equipped to flourish hang around in the engineering major for a couple years before the inevitably fail out, having to then take on more debt to switch majors and finish their degree - or, even worse, to graduate someone with an engineering degree whose skills are so poor that they can’t get a good job anyway. Getting your dreams squashed as a freshman in college has far lower stakes than getting your dreams squashed by the job market as a 23-year-old. The idea that we should just let students breeze through prized majors regardless of talent is based on the patently false notion that everyone is equally equipped to be an engineer, when almost no one in the field actually believes that.

Now, yes, I think that you might have situations where students are right on the cusp of being talented enough to secure a financial existence somewhere near the median of a competitive technical field but instead choose to take majors where the median pecuniary outcomes are far worse. And you have some edge cases where impressionable students will end up markedly less happy because they made that choice, students who could have used a heavier hand pushing them in the direction of mercenary educational choices. Those students certainly exist. However….

There are almost certainly more students who pursue majors they aren’t equipped for than their are students who are insufficiently career-oriented when they choose one

Students who are generally cognitively talented are very likely to be fine economically regardless of the field they choose

Those talented students who are (say) intent on going to film school to be directors are not going to be dissuaded from their creative ambitions or lifestyle goals by average salaries on a chart

I simply don’t think it’s true that the message that STEM graduates make more money isn’t getting out there; we live in a STEM-supremacist culture and “learn to code” has become an unavoidable conservative meme

A lot of people overestimate the strength of these major-income relationships and underestimate the spread; we’re talking about really wide within-field variance here, and as an individual person, you are always an individual data point who could be the two-sigma case in either direction

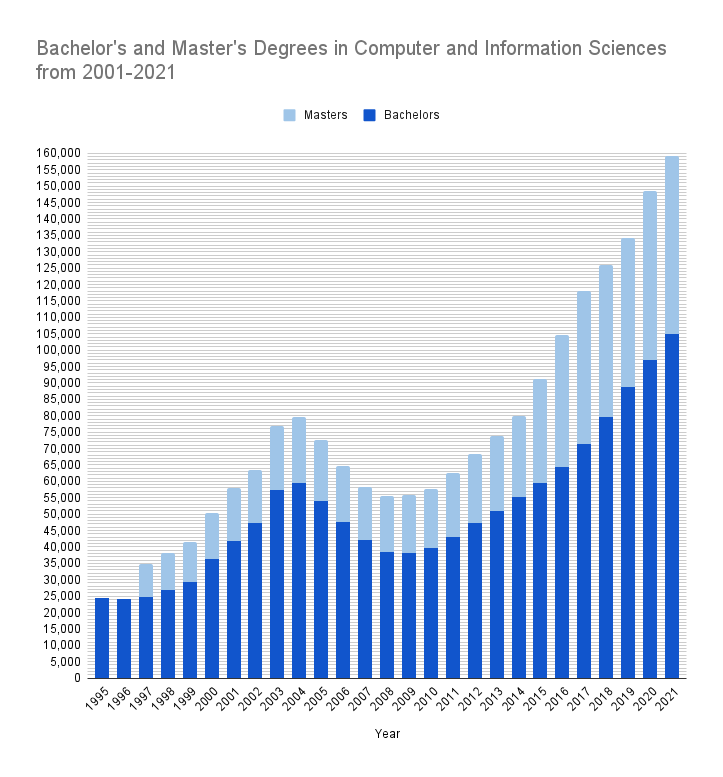

As I constantly point out, the price of educated labor is subject to supply and demand like any other, and flooding fields with new entrants results in worse economic conditions for people in them - you’d still rather be employed as a programmer than almost any other job in purely financial terms, but the entry-level coding job market has gotten far harsher for entrants because of decades of “learn to code,” coding boot camps, and Silicon Valley worship. Do you think this is a entry-level-worker-friendly scenario in computer science?

Again, of course the average programmer is fine. But to be the average programmer you have to a) become a professional programmer and b) be good enough to be average! I have a friend who’s an independent contractor who does back-end web development for a lot of financial and insurance firms. Last year I asked him how he felt the average newly-minted computer science BA was doing in the labor market, in 2023. He shrugged and said, “I don’t know, can they code?” And that’s the whole game, isn’t it? The question isn’t so much what your major is, the question is, are you good at what you do? The major and degree help to give you the necessary skills that you need professionally, yes, but you can only access those skills if you have a certain baseline of underlying ability. And your diploma is mostly valuable to you to the extent that it acts as a signal to employers that you’ve got that baseline of ability. Meanwhile, employers believe that the signal is far stronger if the degree says Stanford or CalTech or UC Berkeley on it, and we’re pumping out tons of mediocre young coders from nondescript state school (like the one where I got my BA) who are really struggling, even though they did exactly what we told them they should do. Unfortunately “go to MIT and then get a job at Google” is not a replicable career path for most. All of the charts and graphs showing average incomes make it appear like there’s a clear path to follow, but like everything else in our economy, this is all a competitive arena where people fight over scarce goods, and winner take all.

All of these conditions became inevitable when we abandoned the labor movement and redistribution as the key to a broadly prosperous economy, and in fact the “college is the pathway to economic success” ideology arose at exactly the time that the Reagan/Thatcher neoliberal vision was becoming the Western default. When you’ve destroyed unions and demonized muscular redistributive programs as a core part of shared prosperity, you need to advance an individualistic vision of economic progress. But if the whole system is bent so that the richest take more and more of the pie, the labor economy will always be a matter of crabs in a bucket. Our contemporary educational philosophy sprang from our economic philosophy, and not the other way around. You can read all about it.

I’ve said many times, and still strongly believe, that I’d rather be a French poetry major with a 120 IQ than a computer science major with a 100 IQ. A lot of computer science types get offended when I say that. But they shouldn’t; the whole point is that the screens in the system ensure that a massively disproportionate number of programmers have both.

Yeah, not sure who that guy from the Atlantic thinks he’s bringing the news to. What, engineers make good money? Ya don’t say!

But the reason engineers make good money is because there are a finite and limited number of people who have the capacity and the inclination of being engineers. If you overwhelmed the market with supply….guess what….they would no longer make good money. But also guess what….the Venn diagrams of the people majoring in basket weaving probably don’t overlap very much with those of engineers. Telling people who have no hope of being engineers that it’s great to be one is truly useless info. The athlete comparo is spot on. To the average person or student who isn’t on track to becoming an engineer, they have no more hope of becoming one than of becoming a major leaguer.

You have to get pretty far down the engineering competence curve before you find someone who can’t create any value. Only a handful of us will conjure billion-dollar companies into existence; a larger but still elite club will earn mid six figures from Big Tech and buy homes in California, but legions of workaday computer whisperers are still clearly worth normal white-collar salaries to a normal companies in regular metro areas.

Whereas even a 95th percentile directing student will never create a single dollar in box office revenue. A 95th percentile literature major will not write a successful book. A 95th percentile history major will not get tenure. These fields are brutally competitive, much more so than engineering, because there is only room for the most successful handful of individuals to create (economic) value with them at all. It’s as if unicorn founder paid a middle class living and Google SWE paid couchsurfing wages, and those were the only two jobs in all of tech.