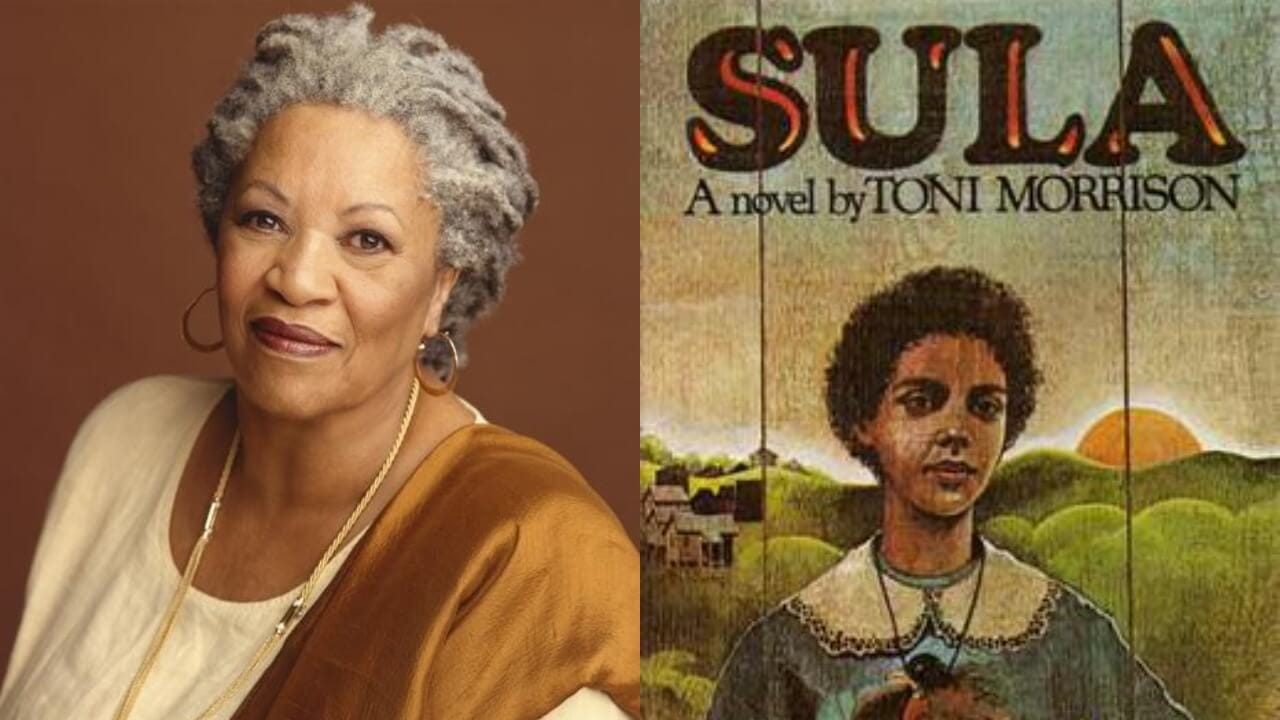

Toni Morrison's Sula, the Great Underrated American Novel

can a masterwork from one of our most celebrated authors be neglected? I think so

Perhaps the most irrational of the many irrational feelings we hold towards books is being offended that one we love is not more celebrated while simultaneously fearing that it will be discovered and thus cease to be our special thing, our perfect secret. For me that book is Sula, Toni Morrison’s gorgeous and challenging story of adolescent and adult rebellion, conformity, family, race, mental illness, and friendship.

Morrison is widely and rightly regarded as a titan in American fiction. After receiving insufficient recognition in her early career, no doubt owing in part to her gender and her race, Morrison became one of the most celebrated and awarded novelists on earth, her work earning her a National Book Award, a Pulitzer, and a Nobel Prize. Stately and magnificent looking, in her latter decades she took on the role of literary nobility, a presence of immense dignity whose work was respected by everyone. She was the queen of American letters. She deserved this status, but I confess it always bummed me out a little - her reputation for dignity obscured how wonderfully weird and playful much of her writing was. A good deal of her stature stemmed from her 1988 novel Beloved, a book of such immense critical and commercial success that it threatened to overwhelm all of the writer’s other work. Beloved helped her to get the Oprah treatment, a famously double-edged form of recognition. At one time it was the most-assigned book in college syllabuses across the country. She continued to publish in her later years but, like many authors, her last novels received little critical love. When she died in 2019 Morrison received the adulation that she deserved. I genuinely can’t think of a major critic who doubts her place in the pantheon.

Yet I find that for all of her fame Morrison’s reputation is… a little loose. That is, I feel that the way she’s discussed sometimes has little to do with the things that I love in her work. This is perhaps just an artifact of my idiosyncrasies as a reader, but I suspect it also has to do with the way that critical acclaim for Black artists tends to feature clichés and commonplaces that obscure the individuality of those artists. (Not out of animus, but out of heavy-handed reverence; don’t put writers into museums of their own reputation, you’re not doing them any favors.) The definition of her peer group is a good example of what I mean. Morrison is semi-frequently grouped with Maya Angelou and Alice Walker, which I find a little baffling; were all three not Black women it would be difficult to name anything the others share in common with Morrison. Walker and Angelou have a host of similarities in their work, in theme and image, that simply do not appear in Morrison’s writing. Those similarities are perhaps not entirely flattering, a New Age-y tendency towards soaring metaphors that operate as much through vague cultural association and familiarity as they do with specificity and purpose. This tendency just does not exist in Morrison’s work. “Wise and confident Black women” is not a literary style.

Walker and Angelou also, frankly, share the status of simply not being in Morrison stratosphere as talents, which of course puts them in company with most everybody. I don’t mean to damn them in a drive-by way. I’m not an Alice Walker fan, but I think a story like “Everyday Use” shows considerable craft. For a long time I thought I didn’t like Angelou, but eventually I learned that Angelou’s work, as with a lot of acclaimed poets, became more predictable and formulaic over time, spending more time showcasing what was critically celebrated rather than claiming new territory. Her early work, I find, is much stronger. If you can get your hands on a copy of her poem “Martial Choreograph” you’ll see something disciplined and wise and sad. (“Your eyes, rampant as an open city” is a line I envy like I envy the lives of the rich and famous.)

Anyway - I also don’t quite understand the relative reputations of Morrison’s books, with Sula’s respected but marginal status chief among my complaints. Look, these perceptions of relative stature are always limited by our own peculiar apprehension of what other people think. My impression could be way out of line with reality. It’s a certainty that some people will read this piece and say, “of course Sula’s great, everybody knows that.” Maybe they’ll be right. But I see Song of Solomon on best-of lists, and I see Beloved, and sometimes I see The Bluest Eye. (I do not see Jazz, which leads me to think other people have the same reaction I had while reading that book - “… why are we in Virginia again?”) I don’t see Sula much on those lists, nor do I find that it’s typically invoked when someone defines Morrison’s reputation. Or, to put this in the crudest terms I can think of, the body of Morrison’s Wikipedia article references Beloved something like 20 times. Sula is mentioned once. I read it again and that just seems so wrong to me.

I have not read Beloved. Mostly this is for no reason; there’s always something else to read, and I read in profoundly snaking and directionless paths. But to the degree that I have chosen not to read it, it’s due to its stature and its reputation. Beloved is one of those books that, to me, feels incredibly weighted with other people’s opinions, with its place in the culture, with its presence in the great assumed curriculum of American books. (Nothing makes me less inclined to read a book than being made to feel that I have to read it.) Beloved sometimes feels inescapable. Which I guess should be a reason to read it, but it all just feels like… baggage. And I have absorbed by osmosis some opinions about the book that make me pause. I’m not sure a ghost story is what I want from Morrison. And some people seem to feel that the book is portentous and self-serious, which is precisely what her best work isn’t. I don’t know. These are stupid reasons not to read any book and, in time, I will read Beloved. I guess I’m telling you this to explain why I can’t say whether Sula is Morrison’s best book. But I can say that it’s a gorgeous, perceptive novel that defies easy categorization and leaves me feeling spent and twisted up inside.

Here is my case for why Sula deserves to stand among the very best American novels, and why you should read it if you have not. I hope it will be useful to somebody.

Sula is the story of a place called the Bottom and two families there, families with daughters, Nel Wright and Sula Peace. They are the twin poles of the novel, two vastly different women bonded by friendship and separated by kin, personality, and circumstance. Nel and Sula live in a Black neighborhood in the hills above a rural white town in Ohio, a neighborhood called the Bottom. Nel comes from what is recognizably the Black middle class, in custom if not in income, a stable family ruled by her mother Helene, an aggressive matriarch who shows the protectiveness common to parents who have come from nothing and fear watching their children return to it. Sula, though, lives with her mother and grandmother, avatars of two warring generations whose relationship and lives are haunted by the scandals that will in turn engulf Sula too. Sula does not so much come from a broken home as one that never was fully assembled in the first place, her mother and grandmother locked in a perpetual cold war. Nel and Sula find each other as teenagers, and Morrison expertly portrays the fierce and complicated friendship of teenaged girls. Naturally, Helene despises Sula; naturally, this only makes Nel love her more.

A tragic accident casts a shadow over their relationship, in ways that will only really reveal themselves later, and creates a complex entanglement with Shadrack, a local veteran who has been driven to madness by World War I and what we would now call PTSD. Tragedy strikes again when Sula’s mother is burned to death and she is left with only her grandmother, with whom she shared a strained relationship even before her mother’s death, an event towards which Sula feels a profound ambivalence. When Nel marries, it seems as though the die is cast: she has accepted the Bottom and turned from the outside world she and Sula both craved. Stung, Sula leaves the Bottom and does not return for a decade, going to college, experiencing the Black renaissance, and sleeping around. When Sula returns to the Bottom, things are both different and the same - the community, her place within it, and her relationship with Nel. Set free from whatever constraints adolescence had imposed, Sula and Nel’s contrasts assert themselves in a painful and final way. Morrison sets the pieces in place and lets us watch the wreckage.

And that’s the novel: two young woman, coming together and apart, joined by their home and their race and their dissatisfaction with everything they’ve known, separated by distance and desire, then unhappily thrown back together again.

The relationship between the two, rocky and sweet and combative and intense, is defined by their differences and touched by recurring tragedy. Nel longs for adventure but struggles to escape from her familial obligations; at times it feels like she’s barely left her mother’s porch. She is thoughtful and reserved but harbors a wild side that she looks to Sula to draw out. Sula is independent and stubborn and more self-consciously Black than Nel, but lacks a vocabulary to express exactly what she wants and wants to be. Her defiance of social norms is by turns admirable and self-destructive, leading her into pointless affairs with much older men that bring her the condemnation of the community and seemingly nothing good in return. This contrast between Nel and Sula is not subtle or meant to be. Nel is the product of a stable home that is loving and constricting, which is two different ways to say the same thing. Nel’s mother is judgmental in the way of protective mothers in both fiction and reality, and as so often happens (again in fiction and reality) it is precisely that judgmentality that fuels Nel’s profound desire to explore beyond her mother’s boundaries. Sula is free, and suffers for it; you can’t help but realize how badly she needs the kind of strict mothering that Nel strains against.

Truly the stupidest way to understand Nel and Sula would be to see Nel as the assimilating Black sellout and Sula as the uncompromising rebel; Morrison is hunting much rarer game than that simple story. Of course, if you do a little bit of looking, you’ll find plenty of that analysis online. But then there are a lot of ways to misunderstand the two, I think. I suppose we need to start with the easy part: the title of the book is Sula, not Nel. This is less a statement of their relative importance and more about the way Sula’s personality overwhelms and dominates that of Nel. Among other things Morrison is exploring how the free-spirited and reckless among us let the rest of us live vicariously through them, hoping that they inspire us to do what we’ve never quite had it in us to do ourselves. And we learn too that there are profound limitations to this inspiration. Though Sula is her greatest influence and she yearns for the outside world, we are told the Nel will never leave the Bottom.

Sula is a complex figure, in some ways the classic picture of a wayward girl and in some ways uncategorizable. Her various rebellions are principled enough to leave you exasperated when her behavior is merely chaotic and thoughtless. (It must have been tempting to make Sula a saintly figure, but this book is not about sinners or saints.) Much has been made of the way Sula troubles the expectations of women in the early 20th century, and I think “gender nonconforming” is a good term for her. (Here I mean in the older sense of not acting according to norms, not as in trans or nonbinary or genderqueer, although I’m sure you can find arguments of that type too.) Certainly it’s valid to point out that the Bottom’s intense and violent judgment of Sula stems in large measure from her frank sexual freedom and refusal to conform. But I worry about applying any identity lens too narrowly, in part because though Sula is the novel’s enduring image it’s the interplay between the two that produces the novel’s drama… and its profound sadness. These are two women, utterly different, but joined together in the ultimately folly of the paths they chose. To say that Sula troubles gender and pays for it is not wrong, but it can never meaningfully explain how Sula and Nel damage each other despite sharing a fierce and strange love.

There’s a little of Jim and Will from Something Wicked This Way Comes here, the same sense of two young people who have adapted to each other in such a delicate way that the changes of young adulthood are bound to upset their unique calibration. More tangibly, I see a lot of resonances with Herman Hesse’s sharp, also-neglected 1919 novel Demian. It too tells of a more reserved and conventional adolescent whose desire for adventure and deeper purpose is activated by a mysterious friend who flaunts the restrictive conventions of the society around them. Both books show how the sparks inside of us can be nurtured by exposure to those whose natures are more wild and resistant to conformity - and how conventionality asserts itself nevertheless. But Demian is a book about the spiritual possibilities for white men in the early 20th century, while Sula is a book about the tangible constraints on Black women of the same period. Hesse’s free spirit is so free that by the end of the book he has become ethereal, a ghost; for Sula, the restrictions of the conventional world and its abundant unspoken rules for women eventually imprison her despite her individuality.

To me nothing in the book is more transporting than the story of Shadrack, who like so many of his WWI peers came home a shattered man. A Lear figure, Shadrack looks on from a place of madness and sees the Bottom in ways that his fellow townsfolk can’t - and, in his strange and askance view, applies a kind of order to what he sees. Shadrack’s National Suicide Day, a way to establish a bit of control onto the most uncontrollable element of human life, is for many the enduring symbol of this novel. Why would someone be moved to create a day on which to end your life? In Morrison’s hands, it’s no wonder at all: Shadrack has been broken, and in wounded defiance he has chosen never to be put back together again, so he imposes his agency on the world through the notion of suicide, which is both a conscious act and a surrender to chaos. The depiction of Shadrack’s experience at war should be studied in every MFA program in the country; the sheer narrative efficiency at hand there is a marvel. Morrison tells a war story that is devastating but utterly reserved, almost blank. We follow Shadrack through his horrors from a haunted remove, everything happening as through several panes of glass. I would block quote the whole thing for you if I could.

And then, almost casually, Morrison produces the most delicate and wrenchingly real depiction of mental illness I’ve ever read. Shadrack has just emerged from a year of institutionalization in an army hospital, wrecked by shell shock:

Shadrack stood at the foot of the hospital steps watching the heads of trees tossing ruefully but harmlessly, since their trunks were rooted too deeply in the earth to threaten him. Only the walks made him uneasy. He shifted his weight, wondering how he could get to the gate without stepping on the concrete. While plotting his course - where he would have to leap, where to skirt a clump of bushes - a loud guffaw startled him. Two men were going up the steps. Then he noticed that there were many people about, and that he was just now seeing them, or else they had just materialized. They were thin slips, like paper dolls floating down the walks. Some were seated in chairs with wheels, propelled by other paper figures from behind. All seemed to be smoking, and their arms and legs curved in the breeze. A good high wind would pull them up and away and they would land perhaps among the tops of the trees.

Shadrack took the plunge.

Here we see the destabilizing terror of returning to the mundane stuff of normal life, stepping out into the reality that does not seem real, seeing with virgin and wincing eyes the world of physical things that becomes, in hospitalization, the most distant of abstractions. Shadrack is, in some sense, a classic literary madman, yet his portrayal is subtle and profoundly unaffected. Shadrack is rude and drunk and paranoid and wild, but he does not suffer from psychosis, which too many writers of fiction seem to think of as the only expression of mental illness. Shadrack does not cut his matted hair, but he keeps his run-down shack in immaculate condition. He lives outside of the polite norms of his community but as a fisherman is a reliable part of its economy. He is unpredictable but in a predictable way, and the people in the Bottom adapt to his rhythms and cycles, effectively making him a part of the scenery - an act of compassion that ensures that no one will ever give him the kind of help he requires.

As Morrison writes of Shadrack, “Once the people understood the boundaries and nature of his madness, they could fit him, so to speak, into the scheme of things.” I think, for many who suffer in the way that Shadrack does, the thought of being fitted into the scheme of things this way is both terrifying and attractive.

One of my favorite of the novel’s many symbols is its simplest, the Bottom itself: the Bottom and its Black residents reside in the hills above, and the rich whites live on the valley floor. This inversion is the result of a con job by a white farmer who had promised a slave he would one day give him freedom and good land; reneging on his deal, he lies and tells the now-freed slave that “the Bottom” refers to the hills, where the soil is dead and choked with roots, the name meaning “the bottom of heaven.” And this is, first, a statement of how Black people suffer from white duplicity. But the symbol is neither uncomplicated nor direct. Though they are poor and suffer for it, the people of the Bottom look down on the white people on the valley floor in more ways than just the physical. “It was lovely up in the Bottom,” the narrator concedes, “… and the [white] hunters who went there sometimes wondered in private if maybe the white farmer was right after all. Maybe it was the bottom of heaven.” In the Bottom suffering is real, but there is nothing maudlin or wounded about the place. The Bottom is the result of white racism, and that bigotry teems at the edges of the novel, and yet Morrison has created a Black space far from white concerns, where the drama that ensues spools out almost indifferent to the vast edifice of racial inequality that waits just outside its doors.

To me one of the great strengths of Morrison lies in her ability to write about race and the Black experience without ever relying on the clichés we have come to expect from themes of race in narrative art, whether created by Black artists or not. In the five Morrison novels I’ve read, she has always resisted the tendency to talk about race purely in the simplistic terms of oppressor and oppressed. Don’t get me wrong: there is no hiding from the basic brute reality of racism in this book or any of the others. Morrison does not dissemble when it comes to America’s racist past or present. The Bottom is a poor and neglected place filled with poor and neglected people, its name a symbol of white duplicity. But there is something profoundly weird about the Bottom, a strange lyric lightness that sometimes makes the book seem almost… magical realist, I guess. And there’s a similar refusal to make the drama at hand here some sort of epiphenomenon of white people’s attitudes and actions. In so much of today’s racial politics, everything that happens to Black people is a function of some earlier decision by white. Morrison’s books show that, however much this attitude might make the prosecution of inequality easier, it also reduces Black agency and thus Black individuality. The Bottom may have been made by a white man, but it is a Black space, a space where Black people live lives and make decisions outside of the orbit of white judgment and white action.

As is always the case for me, the prose comes first, and Morrison’s prose in this book is spare, still, immaculate. Like the best realizations of the American style, Morrison accepts the philosophy of minimalism but not its form, describing as much as necessary but no more, without the clipped and straining rhythms of showy minimalist writing that have infected so many American writers. Or, to be less precious about it, this is a writer, just past 40, who was reaching the full zenith of her powers and writes both unconstrained by insecurity and without carrying the weight of self-consciously grasping for greatness. The woman could write a sentence.

Her bare feet would raise the saffron dust that floated down on the coveralls and bunion-split shoes of the man breathing into and out of his harmonica.

No one would ever be that version of herself which she sought to reach out to and touch with an ungloved hand. There was only her own mood and whim, and if that was all there was, she decided to turn the naked hand toward it, discover it and let others become as intimate with their own selves as she was.

There in the pantry, empty now of flour sacks, void of row upon row of canned goods, free forever of strings of tiny green peppers, holding the wet milk bottle tight in her arm she stood wide-legged against the wall and pulled from his track-lean hips all the pleasure her thighs could hold.

If milk could curdle, God knows robins could fall.

The rhythms of this book are the closest I’ve found to the quality that enraptures so many about The Great Gatsby - a quality of lyricism and artistry that comes from a bountiful and exacting prose voice which Morrison camouflages as the plainspoken and repressed style that has, misunderstood by so many, held American fiction hostage and ruined so many young writers. Fitzgerald, and then Morrison, chased the same white rabbit down the same dark hole and were not ruined. Some authors deserve special recognition for piloting books confidently up to the reef of the American style until they scraped the rocks that wrecked so many others and yet sailed safely away.

Do I have complaints? I guess so, maybe. In a book that is so relentlessly resistant to big moments, Sula’s mother’s death strikes me as a little stagey. Perhaps I find the latter half of the book less ruthlessly disciplined than the first half, a little more given to rumination and thus a little more self-conscious, a little more obviously an act of construction. Sula’s actions in the second half of the book, particularly her various betrayals of Nel, seem entirely in keeping with the character we met as a teenager, but occasionally the conflict does seem a little… overdetermined? Inevitable, in the sense of being pre-plotted for dramatic effect, rather than an expression of the organic architecture of the story we’ve been told? I don’t know. This is pretty abstract and my heart’s not really in it. It’s hard to find much in the way of flaws, other than the that the book makes me sad, which is its purpose. I just love it. I truly do.

When Morrison died, her life and work were celebrated as a giant of American fiction, as was appropriate. Yet I found that Sula was seldom mentioned, in part because of the way that so many of the accolades failed to escape the immense gravity well of Beloved. Song of Solomon, too, eclipsed Sula in remembrance, and no surprise there; Song of Solomon is a far more self-conscious and overtly ambitious novel, and so more likely to receive awards and critical adulation. It is also, to me, clearly the lesser novel. I say that with no disrespect. I admire it without reservation. But Sula is the work of a younger and freer artist, and a story that seems less concerned with the ostentatious pride common to those books that chase the title of Great American Novel. It does with silences and subtleties what Song of Solomon does with the sweep of history. Milkman’s story is baroque and teeming with life, to me a peer to (and contrast with) Augie March. But Sula is the book to which I’d rather return, in part because it’s so much tighter and more constrained. It’s a story about a small place and a few people within it, revealing little it doesn’t need to in order to cast the greatest light on what it does, a work of chiaroscuro.

Were we forced into the juvenile-but-inescapable task of assigning tiers to great books, I would perhaps concede that Sula is not at the level of Moby Dick, The Invisible Man, or Huckleberry Finn. But even if I did, I would do so saying that while those books are “greater,” Sula is just as wise, subtle, and true. And, in its way, devastatingly American, the America of places like the Bottom - quiet little out of the way neighborhoods where the machinery of racism and inequality grinds along, so natural a part of the world that those who suffer under them regard them as part of the endowment of God. The Bottom is no less a symbol of Black America than Ellison’s Harlem and HBCU, no less a site of the basic American struggle than Melville’s Atlantic ocean, no less a setting in which we learn of the American capacity to reconcile, and its limits, than that of Huck Finn. I think Sula is a book for anyone to cherish. Why it’s not universally regarded as a masterwork, I have no idea. But now it can be your hidden gem too, your secret favorite, your special thing.

If you pick up the Vintage International paperback, which seems to be the most common edition, my advice is that you not read Morrison’s brief author’s foreword until after you read the novel. It’s insightful and interesting history, and unsurprisingly exquisitely written, but it’s never good practice to read an author saying “and what I meant by that is this” before you’ve read the book itself, particularly when it’s been written from the perspective of decades later. Just some free advice.

I've never wanted to read a book so badly after a review. Dear God, please triple the hours in the day.

I googled “Martial Choreograph” and found a copy on an old RSS feed from an earlier post https://deboer30.rssing.com/chan-29998540/latest-article1.php