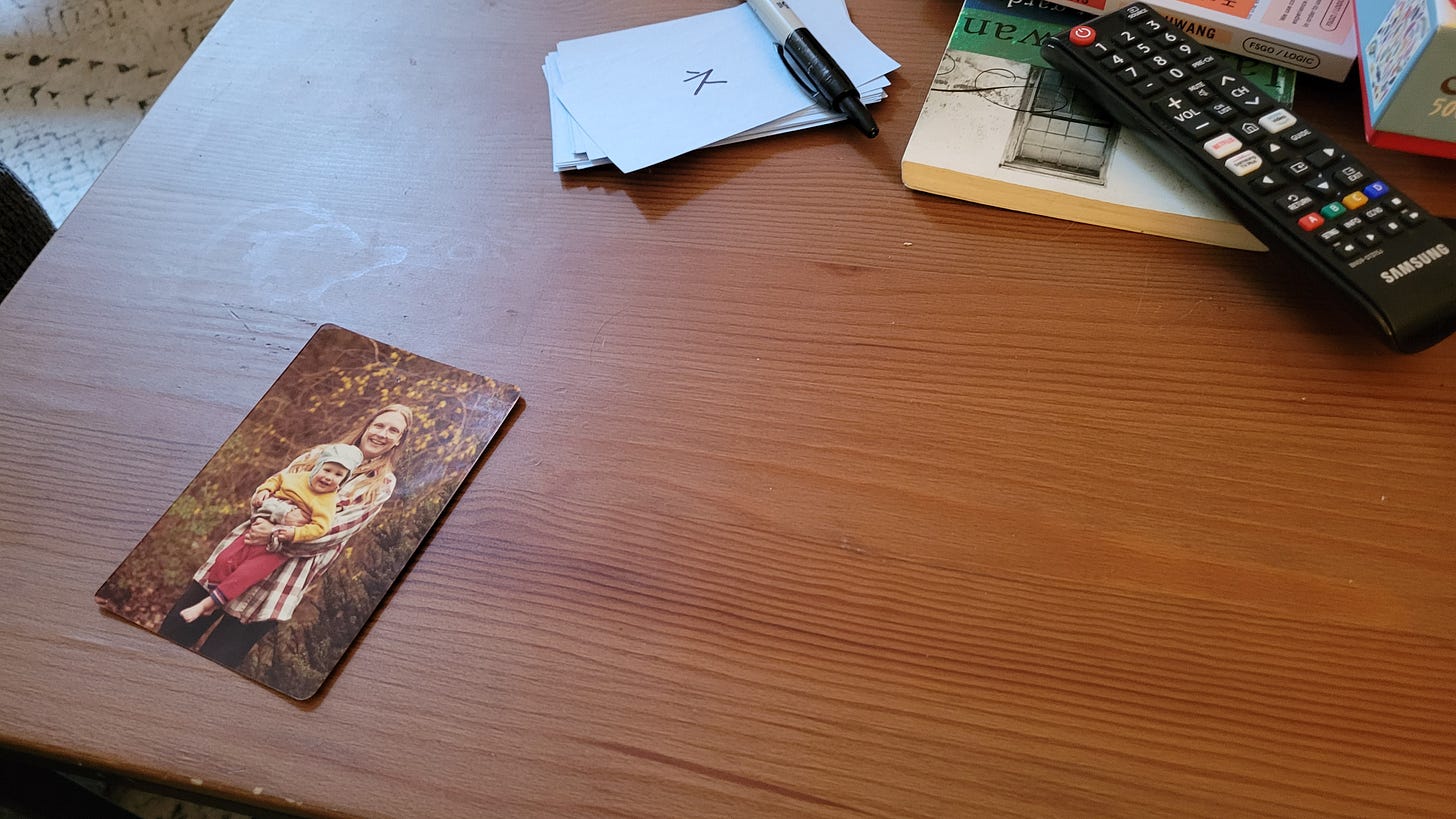

My mother, who I have made in paper

Dear Freddie, I have been reading you since 2016…. I wonder if you might consider my reader request. About five weeks ago I gave birth to my third (and last!) child, a beautiful healthy baby boy. It was a difficult delivery. After it was clear that he and I were healthy and I had some time to hold him, my husband told me that my mother had succumbed to her breast cancer while I was in labor…. We knew it was coming, but between Covid and [the pregnancy] there was no way I could return to Canberra to see her before she went…. You have written so movingly about losing your own parents to cancer, and I hoped you might write a little about your mother and her illness for me, or about children losing mothers, or however you would like. Either way, I will be making a donation to the American Cancer Society as a kind of payment for your attention and your words. Be well.

My memories of you are paper-thin fables, at this point, legends passed down through generations, the oral histories of an ancient people. I think back to the stories I told when I could remember them, and now I remember only the remembering, and that not well. Once you showed me how to press butcher paper against a gravestone and rub it with a crayon to create a facsimile of a marker of what once was alive, and such are my memories of you. Remembrance of grief outruns the joy that died and provoked that grief, and then the grief too recedes into a cool smolder, and in the end all that is left is the ash of what was once the hottest and hardest of human feelings. Little else remains.

And yet I know things about you, I know them by heart. I know you to be lithe, antsy, easy to grab hold of. You ambled along in life, both purposeful and relaxed, like a cat padding unhurried across a roof. Famously kind, famously stubborn, famously hotheaded. At your funeral a friend described how you told her, right after her infant died, that she would go right out and get pregnant again, and her great anger at you for saying so. “Presumptuous woman!” she said, meaning you and your thoughtless sunniness, your ebullient and clumsy light. “And she was right” was the next part of her story, for that was what she needed to hear and to do and that was what she did. I could never say what you said to her; I couldn’t counsel anyone else to say it, couldn’t imagine a scenario where it would be the right thing to say. But you did say it, and she said you were right to do so, and that was part of a magic that was all your own. There is no word for the thoughtlessness that springs from a totalizing belief in the power of love to heal all things, but if they name such a thing they should name it after you. For now it will have to suffice that when you died they gave the arboretum your name, for trees are wild things, intricate and strong, and like you they lift their fingers skywards to grasp the sun.

Everyone can spot a motherless child. I lived for years shrinking from that pitying gaze; I hated that they knew and hated myself for letting it show. The demand your heart makes is one that cannot be satisfied, the demand for a space with endless compassion and no pity, a place where every hurt is understood only in the ways you would like to understand it yourself. I hid and I hid and I hid and I hid…. But those who know must pity you, and if they’re compassionate they cast you in their mind as the protagonist of some old fairy tale, one of our innumerable stories of orphaned children forging ahead towards some trite moral that explains the purpose behind the pain. In reality all you can do is trudge along until you’re old enough that motherlessness seems less tragic. For all my resentment towards being pitied, I felt at sea when I was old enough that the pity was gone; I found that, despite myself, I had become an orphan, that it had become my identity. Loss eases into the hidden spaces of your personality like the moisture behind the walls in your bathroom that rots away unseen for years. It’s not beautiful to be your pain or noble to be your trauma, no matter what our culture tells you. In fact I find it quite pathetic when I find the way my hardship persists in myself, and I find it in myself all the time. But we have a way of becoming the mindset in which we live, and in those days I was motherless and afraid.

And yet today I feel that everything is in its place. I have finally finished deciding what name to give you, how to draw your picture in my own book. A mother’s love should mean something, and for me it does, something deep and simple: a mother’s love is to me that yours is the finger I cannot clutch.

Mothers, this is your gift, your glory. For now you exist to your children in all of your fleshy corporeality; you are a body first, and it is from your literal bosom that comfort springs. In time they will wander farther and farther away from your physical embrace, but you will always be their embodiment of safety and warmth, and it is that ideal which will inevitably recede away from them, the inescapable loss that we name maturity or adulthood in the vain hope of rendering it bearable. We live in the shadow of our longing for you. Yours is the call we hear, insistent and indistinct, on every spare breeze that passes softly through our windows. My mother has only been that longing, her absence her only presence in my life, and now even that is gone. But what is left is both delicate and indelible. I do not believe in God, the soul, or an afterlife in which my mother waits for me. The universe is not that kind. But I do believe, in some sense I feel but cannot know, that she lives and lives and lives again, and that someday I will stand in front of her and the world unashamed of what I am, and in that moment I will find some way to repay her for all the things she taught me, the wisdom she lent in silence and in murmurs by my bedside, in pressing her hands against my cheeks to help me sleep, all the things she told me that I needed to hear and did not understand.

Perhaps I will have the chance, someday, to repay that love. For as the man said, love returns to the love that made it. When you are a mother, you are that love. You were always that love.