They Still Won't Say That They're Sorry

deindustrialization's victims and the wonks who won't acknowledge them

In this recent appearance on Ezra Klein’s podcast, Harvard economist and Obama admin enforcer of neoliberal consensus Jason Furman is teed up to express at least some remorse for the Americans who were devastated by deindustrialization. Klein notes that a number of economists have argued that the human costs of deindustrialization were far higher than was predicted during the fights over NAFTA and similar free trade agreements. It’s a softball windup designed to give Furman the opportunity to say “The human costs in these places was deeply unfortunate, and we should have done far more to help them, but….” And then he could go on to treat the terrible costs of deindustrialization as some minor downside to the overall benefits of globalization. Remarkably, he does not! He does not say a single word to even empathize with the people left behind in these communities, let alone suggest that the hyper-educated elites who created this policy outcome - people like him - got anything wrong. It would have taken him 30 seconds to extend some parenthetical sympathy. He declined.

You can listen for yourself. Klein says, “some really celebrated economists will say the deals we made had a much more significant and negative effect on a lot of communities in America than we were told.” And Furman’s response is to say “I’m much more unapologetic than what you just laid out.” Extremely compassionate, Jason!

It’s remarkable. The amount of human devastation in the deindustrialized spaces in the United States has been unthinkable. Entire communities where the most common source of personal income is disability payments, fentanyl addiction rates in the double digits, 60+% unemployment rates among workers aged 18-25, collapsing municipal services, a doom loop of people fleeing all of that destruction which in turn devastates the tax base even more. At an extreme, you have a place like Gary, Indiana, where the population is lower than it was in 1927, where the violent crime rate is 318% higher than the national average, where residents live scandalously short lives, where fully a third of all residents live below the poverty line…. You could do the same kind of analysis in Detroit or Youngstown or Akron. These social problems are often dismissed as being a problem for white people, which is absurd given the demographics of these regions; arguably, no group suffered more from deindustrialization than the Black middle class. It’s a scandal that such terrible conditions exist anywhere in the United States for any reason. That the policy effort was made to benefit huge corporations and the wealthy only makes the whole situation more inexcusable.

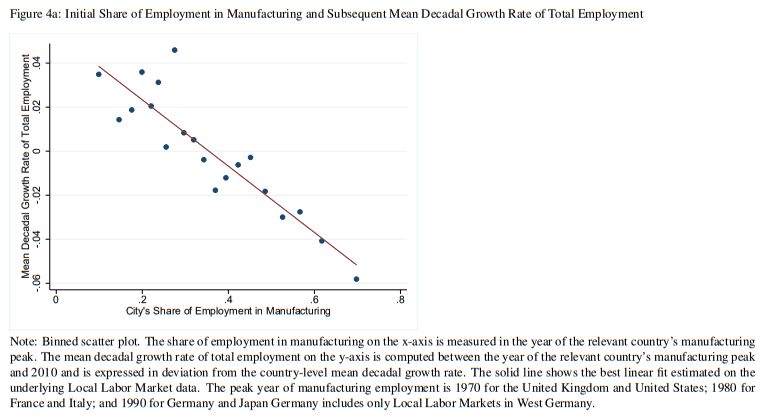

Furman does a little kabuki by saying that most of the growth in American inequality, so broadly fretted over, came between 1980 and 2000, not after. Setting aside whether this is a remotely meaningful statement on deindustrialization writ large, it’s hiding the football of manufacturing employment:

It’s not just that this job loss happened, it’s that it was meant to happen, predicted to happen. Some defenders of NAFTA specifically and free trade generally frequently insisted that predictions of mass closures of American plants and factories was just doom-saying; it was not. Others, though, steered into it, arguing that yes there would be job loss, but it would be worth it. (This kind of “that’s not happening/it’s happening and it’s good” arguments have a constant presence in American politics.) Meanwhile, it’s largely forgotten now, but a huge part of the push for NAFTA was based on stoking anti-immigrant rhetoric - supporters argued that the policy would improve Mexico’s economy to the point that Mexicans would no longer seek to enter the United States illegally for work. Mexican undocumented immigration rises and falls with the American economy, but the predicted cratering of illegal crossings simply didn’t happen. So you have a policy sold on an ugly xenophobic basis that didn’t even have the anti-immigrant outcomes supporters insisted it would.

That decline in that chart, there, represents a lot of human devastation. You are certainly free to argue that the overall impact was a net positive for American workers or that the impact on global poverty rates was worth it or that this was inevitable etc etc. That’s all fine. But you have to count the costs, and what I find so relentlessly vulgar about people like Furman is that when given the opportunity to do so they very often crawl into the shell of insisting the policy choices were the correct ones. Even if you think the globalization policies that caused deindustrialization were ultimately the correct ones, you have to account for the losers and what it cost them. But in big fights over NAFTA, before passage and after, pro-globalization forces have relentlessly insisted that there would be no meaningful costs at all, with attack dogs like Brad Delong relentlessly mocking anyone who questioned the rosy narrative. Even The Economist, where I believe Friedrich Hayek’s ghost works as a columnist, has stated plainly that the losers of the free trade policies of the past 30 years have lost very badly indeed. Dean Baker and Robert Scott, not exactly UAW executive board members, have argued that NAFTA has cost the United States 600,000 jobs since its implementation. Furman, it would seem, cannot bring himself to say the same.

Even the Cato Institute dismisses these costs with the aside that “Disruption, of course, can still be painful for certain manufacturers and workers,” before barreling on talking about how great free trade is. And that’s Cato! They don’t even pretend to care about poor people. For the record, I’m not unwilling to entertain the possibility that the net impact on jobs from these polices was positive. But while jobs may be fungible in the eyes of fancy doodah economists, they most certainly aren’t for the individual people living in actual devastated communities. An autoworker who enjoyed a stable and fulfilling life who has his job “disrupted” out from under him is not going to feel much better about it because some 22-year-old in Berkeley got a job. The implicit notion that people who lose jobs in one industry in one part of the country can simply get a different one in a different industry in a different part of the country is absurd. That’s how you get these ludicrous fables about how laid off uneducated machinists in their 50s, who worked the same job for 30 years, are going to learn to code and go work for Google. If you think all of this pain was necessary, be a fierce and, yes, unapologetic supporter of robust public spending to ameliorate the economic devastation these people could not possible control!

All of this was more or less to plan, by the way. Barack Obama represents many things, but more than anything he represents the total takeover of the Democratic party by the Brownstone Brahmin class. Obama and his team of bloodless wonks steered policy in a way that benefited upper-middle-class professionals and the college educated again and again, and indeed, once the manufacturing output of a developed country declines, inequality between uneducated workers and educated workers starts spiking. So Obama’s indifference to the costs of deindustrialization - the right people win. Unsurprisingly, standing by in indifference accelerated the erosion of white working class support for Democrats. This should have caused every alarm bell to ring, since white working class support was crucial for Obama’s electoral victories. But his administration didn’t appear to notice, seemingly content to become more and more thoroughly a vehicle of wealthy urban liberals who supported faux-radical social and cultural politics while quietly preferring the economic conservatism that would benefit them. Who was around from the relevant parts of the country to make Obama care about the people rotting to death in the Rust Belt? Was Furman going to run into any of them at the Harvard faculty lounge? It’s a profound and intractable problem in modern progressive politics: the people who gain influence in progressive spaces are almost universally drawn from a tiny class of hyper-educated professionals, rather than the natural constituencies of progressivism. Constituencies like those in poverty and the working class.

I am increasingly convinced that Chuck Schumer’s notorious comment before the 2016 election is a Rosetta Stone for the 21st century Democratic party. Schumer said, “For every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia, and you can repeat that in Ohio and Illinois and Wisconsin.” Whoops! That didn’t happen. The states most associated with deindustrialization - Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin - went for Trump. That was a bad decision on the parts of those voters, but I understand even while I don’t approve; when the National Honors Society members that ran Obama’s administration governed with total indifference for the suffering happening in these states, they guaranteed a backlash, and it’s our bad luck that that backlash came in the form of Donald Trump. It doesn’t matter if the choice to vote for Trump was a good or bad decision. It was a consequence of the supposedly progressive party forgetting the most central and sacred duty of progressivism: to make sure no one is left behind.

The thing that really gets to me is…. I don’t think Schumer was just predicting. I think that was a statement of preference as well as prediction. I think the Democratic donor class, as well as the policy apparatus, as well as the people who do all the ground work in the various offices, are all people from a very particular slice of the American population, a self-regarding elite slice. And it seems like Democratic leadership was more than happy to say “Sayonara!” to the blue collar voters that Schumer disdained, eager to be the party of Lena Dunham and HR professionals, of architects and higher ed bureaucrats. Those moderate Republicans whose votes they coveted may have been Republicans, but hey, at least they were people who knew what intersectionality means. This all looks like a conscious decision to me, and it’s one entirely in keeping with the priorities of Barack Obama, who always aspired to be the cool dad of Greater Park Slope, more eager to share his playlists than to pay attention to the great mass of the country which never had the option of going to an Ivy for grad school.

The bottom line is this. Opening up the United States to unfettered free trade had devastating consequences for a number communities in our country, many of them filled with racial minorities and immigrants. Jobs that had brought not just economic security but a sense of community and purpose to hundreds of thousands of people who lacked the social capital of the college-educated class were systematically destroyed. This had all been predicted by the critics of globalization in the 1990s. (Even Ross Perot, who always sounded like he had just been concussed, got it right.) And yet still the people left behind were given just about zero organized assistance of any kind, told to adapt, lectured to about “creative destruction,” treated like they were just grievance-mongering racists despite the fact that very many of them were Black. You think globalization was worth it, a net good, cool. You still have to account for those whose communities were destroyed by those policies, and no one ever did, most certainly including the Democrats, most certainly including Obama. And that’s immoral.

Someone tweet this at Furman.

![Somebody goes around Flint, Michigan posting signs like these at abandoned buildings and lots [OC] : r/AbandonedPorn Somebody goes around Flint, Michigan posting signs like these at abandoned buildings and lots [OC] : r/AbandonedPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F320281af-0247-4ffb-846b-70efa984b2ae_3840x2160.jpeg)

This post rolls a whole lot of things together in a way that isn't really sensible to me. NAFTA came into effect in 1994 and I definitely buy that it accelerated deindustrialization. But deindustrialization started in the late 70s; manufacturing share of employment peaked in 1979, a full 15 years before the policy Freddie is blaming for its decline. But then also we're focusing on Jason Furman and Obama, who were in power from 2008-2016, which is a further 15ish years after NAFTA went into effect? There's definitely continuity of thought in this area from Clinton to Obama, but what exactly did we want Furman to do?

I do want the Democratic party to pay more attention to helping the Rust Belt and similar areas, but we still have to ask: are the alternatives to globalization actually better? Is it really preferable to just have everyone be poorer, for most things to cost more, for most people to make less money?

“ That the policy effort was made to benefit huge corporations and the wealthy only makes the whole situation more inexcusable.”

The public also loves cheap shit from China. It’s not all about bad policy being imposed by “elites” from above. It’s also the public’s voracious appetite for the benefits of globalization.