The Modern Curse of Overoptimization

I know a guy who used to make his living as an eBay reseller. That is, he’d find something on eBay that he thought was underpriced so long as the auction didn’t go above X dollars, buy it, then resell it for more than he paid for it Classic imports-exports, really, a digital junk shop. Eventually he got to the point where, with some items, he didn’t ever have physical possession of them; he had figured out a way to get them directly from whoever he bought an item from to the person he had sold the item to, while still collecting his bit of arbitrage along the way. This buying and selling of items on eBay, looking for deals, was sufficient to be his full-time job and pay for a mortgage. But the last time I saw him, a few years ago, he had gotten an ordinary office job. He told me that it had become too difficult to find value; potential sellers and buyers alike had access to too many tools that could reveal the “real” price of an item, and there was little delta to eke out. He’s not alone. If you search around in eBay-related forums, you’ll find that many longtime sellers have reached similar conclusions. The hustle just doesn’t work anymore.

I don’t suppose there’s any great crime there - it’s all within the rules. And there does appear to still be an eBay-adjacent reselling economy; it’s just that, as far as I can glean, it’s driven by algorithms and bots that average resellers simply don’t have access to. It appears that some super-resellers have implemented software solutions to identify underpriced goods and buy them automatically and algorithmically. They have optimized the system for their own use, giving them an advantage, putting other sellers at a disadvantage, and arguably hurting buyers by eliminating uncertainty that sometimes results in lower-than-optimal-to-sellers prices. This is all in sharp contrast to the early years, when my friend would keep listings for lucrative product categories open - in separate windows, not tabs, that’s how long ago this was - and refresh until he found potential moneymakers. That sort of human searching and bidding work stands at a sharp disadvantage compared to those with information-scraping capacity and automated tools. It’s a good example of how access to data has left systems overoptimized for some users. One of the things that the internet is really good at is price discovery, and these digital tools help determine the “optimal” price of items on eBay, which results in less opportunity for arbitrage for other players.

My current working definition of overoptimization goes like this: overoptimization has occurred when the introduction of immense amounts of information into a human system produces conditions that allow for some players within that system to maximize their comparative advantage, without overtly breaking the rules, in a way that (intentional or not) creates meaningful negative social consequences. I want to argue that many human systems in the 2020s have become overoptimized in this way, and that the social ramifications are often bad.

Getting a restaurant reservation is a good example. Once upon a time, you called a restaurant’s phone number and asked about a specific time and they looked in the book and told you if you could have that slot or not. There was plenty of insiderism and petty corruption involved, but because the system provided incomplete information that was time consuming to procure, there was a limit to how much you could game that system. Now that reservations are made online, you can look and see not only if a specific slot has availability but if any slots have availability. You can also make highly-educated guesses about what different slots are worth on the market through both common sense (weekend evenings are the most valuable etc) and through seeing which reservations get snapped up the fastest in an average week. And being online means that the reservation system is immediate and automatic, so you can train a bot to grab as many reservations as you want, near-instantaneously, and you can do so in a way that the system doesn’t notice. (Unlike, say, if you called the same restaurant over and over again and tried to hide your voice by doing a series of fake accents.) The outcome of all this is that getting a reservation at desirable places is a nightmare and results in a secondary market that, like seemingly everything in American life, is reserved for the rich. The internet has overoptimized getting a restaurant reservation and the result is to make it more aggravating and less egalitarian.

As has been much discussed, nearly the exact same scenario has made getting concert tickets a tedious and ludicrously-pricy exercise in frustration.

Dating apps are perceived to be so annoying and exhausting to use that one of the biggest is getting an overhaul. When these apps were novel and new, people approached them with a certain degree of innocence, and indeed because there was a residual sense that it was embarrassing to meet partners online, many users engaged with a self-defensive lack of seriousness. But as more and more people crowded onto them and any remaining stigma evaporated, the competition got more and more fierce, and some determined users learned how to manipulate the interfaces and systems to maximize their chances of getting dates. In 2016 or so, a Buzzfeed piece titled something like “Seven Tips to Level Up Your Bumble Game” would be a lighthearted lark. Now, such things are serious business. There are all manner of creepy-but-efficient strategies that are traded online. Once people found opportunities to game the system - to optimize - and worked them relentlessly, until the sites were filled with the same annoying tricks.

Finding a first line to lead with on Tinder has been a source of constant agita. Years ago one user reported on Reddit that he had achieved great success by saying “there she is” as his first message. He posted some of the flattered, flirtatious replies that he got back from women. You’ll never believe what happened next! This became enough of a go-to move, at least in some circles, that many women groaned when they received “there she is” and automatically began to reject such men. Dating apps are interesting in that there is an organic and reactive target, so it’s not really possible to overoptimize with a specific strategy. But the overarching approach of doing A/B testing with various material, and developing stock moves and lines that have nothing to do with the specific recipient, represents a classic scenario of overoptimization. Such behavior may very well benefit the particular person looking to optimize their (I mean, let’s be real, his) chances. But it has negative effects for his potential matches, who will usually prefer not to be treated as a puzzle to crack, and on men on the site who don’t engage that way and would prefer to maintain an authentic approach.

There are also many complaints about these apps and services getting worse in terms of their core features. This piece argues that a core problem lies in apps now hiding people you’d like to match up with behind a velvet rope, which you of course must pay to pass through. This is definitely an example of a platform exploiting its userbase for more money, and in no sense do I want to exonerate any internet service for goosing profitability in a way that makes the system worse. (Which is just about all of them.) But bear in mind that while a paywall may very well be an annoying and exclusionary screen keeping out some users, for those who pay it’s an attempt to achieve greater optimization; the paywall not only gives them access to more potential matchups but, crucially, keeps some of the competition out. And so while nickel and diming dating apps are an example of enshittification, they are also an example of overoptimization - when a given digital technology enables at least some players to leverage its systems in a way that provokes negative social consequences for most.

Lauren Oyler’s recent essay collection No Judgment begins with a funny story about how the writer Adam Dalva set about to become one of the biggest reviewers on Goodreads. He achieved this goal by shamelessly gaming the systems in that site, deconstructing how they work until he was able to arrive at a clear process to become more and more prominent on the network. Of course, as Dalva cheerfully acknowledges, the way he does so degrades the overall level of information for other users; optimizing his own position necessarily entails reducing the organic value of his opinions. And if everybody starts doing that…

The paid newsletter economy of which I’m a part has been argued to be a threat to the traditional way that journalism has been funded, through bundling. Real journalism, involving sending people out on often-expensive fact-finding missions, has never really been profitable. Newspapers survived by paying people to opinionate, or design crosswords, or draw comic strips, or write recipes, etc., all of which was ultimately cheaper and more profitable than actual newsgathering. The internet has pulled those bundles apart, such that you can get free comic strips, free games, free recipes, and (so much) free opinion, which threatens the viability of the news business. And paid newsletters in particular afford writers price discovery - they can now find out what the market will bear for their writing, which is to say, optimize their writing income. Which means that some have now priced themselves out of working for traditional publications, who could use their bundling power. Newspapers have a lot of problems, but certainly the ability of talented workers to simply set out on their own and know exactly what they’re worth is a big one. Price discovery information is in and of itself neither good nor bad, but from the standpoint of someone trying to keep a newspaper afloat by (in part) paying writers less than what they’re worth, the newsletter economy amounts to an overoptimization of the media business. Meanwhile, newspapers are dying.

Consider travel. Complaints about traveling have become relentless and unavoidable. In particular, there’s a widespread sense that every place you might want to travel to is stuffed to the brim with tourists (like you), which for many defeats much of the aesthetic and emotional point of traveling. The world is a big and rapidly-changing place. For much of the history of air travel, the number of places that most people could realistically travel to was restrained, in part because there were few air options and little lodging but more because they simply didn’t know to go anywhere else. Travel gurus like Rick Steves made their living by sharing “secret” destinations with those who purchased their books or read their magazine columns. And while those audiences could be large in relative terms, in general few average Americans knew that they might enjoy Vienna or Patagonia or Bali more than Paris or the Swiss Alps or Hawaii. (To say nothing of Riga or the Jotunheimen mountains or Ibo Island.) But the mass adoption of the internet changed all that. Now, there’s not just “best hidden gem travel” Google results available at a moment’s notice but an innumerable amount of online spaces where people share travel tips. Suddenly there’s no secret travel information anymore. The idea of a hidden gem has lost almost all meaning, and that’s true in the macro (“Check out Bratislava!”) and the micro (“I know this wonderful hidden-away café out there, you have to check it out”).

Combine all of that free knowledge with plummeting costs for airfare during the period of mass internet adoption, and you have a recipe for this sort of thing - thousands of residents of the Canary Islands marching in protest against the negative effects of constant mass tourism. Whatever degree of obscurity once protected places like the Canary Islands, or Santorini, or Iceland is long gone, and cheap air travel ensures that they get throngs of travelers descending on their shores, which hurts the quality of life for locals and, perversely, for tourists. Once upon a time, the reason you might go to Iceland is to experience quaint Nordic life far from the hustle of the urban Western world and to go to natural spaces where you can be truly alone. The former is certainly gone in Reykjavik and the immediate environs, and while you can go out and find solitude as a traveler in the countryside, it’s considerably harder to do so. Iceland is also a good example of a common problem, which is that the economy has become too dependent on tourism (overoptimized for tourism) to take major steps to shut it down but where the amount of tourists becomes more and more unbearable. And there are also spillover effects, such that people who would once have gone to Iceland now go to Greenland to experience that austere and inhospitable solitude, which in turn pushes another unblemished landscape past what it can healthily sustain….

By the way, airlines are starting to crack down on their frequent flyer mile programs. Why? Because tricks used to exploit them have become widely available online, no longer secret in any sense, meaning there’s too many people using them, prompting the airlines to make the system worse for everyone.

Travel is too accessible for some of the traditional pleasures of travel to survive. Information about where to travel to is too accessible for some of the traditional pleasures of travel to survive. I’m not going to make a value judgment about which virtue is more important, accessibility or preserving the experience. The point is that a lot of travelers find their own travel to be less fulfilling because of the very systems that enabled them to take the trip in the first place.

Overoptimization doesn’t have to be purely or primarily about the internet. Maybe Mount Everest is the ultimate example. Once, climbing Mount Everest was reserved for true experts. Then commercial guides began leading dedicated amateurs to the summit. Over time, the techniques for getting climbers with little or no experience up the slopes got more and more sophisticated. As the danger and difficult went down, the number of entrants went up, and all manner of attendant environmental and social problems followed. The industry that takes people up Mount Everest became overoptimized and now the experience has, at the very least, become less emotionally fulfilling and memorable. I can’t be alone in thinking that perhaps the only thing that will fix the problem is enough potential climbers seeing images like this one and concluding that it’s actually lame to climb Mount Everest. I personally struggle to see how it’s some sort of great achievement, at this point, given that thousands upon thousands of people have gone up there at this point. But to each his own. The problems still remain - the ease with which guides are able to take teams up the mountain now means that (paradoxically) the threat of mass death from an avalanche or sudden storm are huge, the area looks like a garbage dump given how much litter and human waste and human bodies have piled up everywhere, and the actual experience that customers are paying thousands of dollars for has seriously degraded thanks to the crowds. The people who organize these things got too good at it and now there are all manner of new problems that emerge with that ease. Overoptimized.

Sports is another decidedly offline pursuit where many have complained of overoptimization problems. With access to more and more information, teams and analysts have an excellent grasp on works and what doesn’t. And this inevitably pushes teams to all adopt the same strategies - exactly what the average sports fan, who craves different styles of play, isn’t looking for. Major league baseball has recently taken some drastic (and to my mind necessary) steps to change the game, as the product had become nearly unwatchable. You’ve heard this from me before. Modern baseball strategy has minimized action on the base paths, despite the fact that such moments are the most unpredictable and fun part of baseball. Adherence to stats created a game where 165-pound shortstops were constantly taking huge hacking uppercut swings because the statheads had decided that slightly increasing the chance of a home run was worth more than hitting to contact, meaning the game had lost some of its basic diversity in playstyles. And now that pitchers have been trained to see velocity as the one holy pursuit of their profession, we are unsurprisingly seeing pitcher after pitcher go down with elbow injuries. We learned too much about how a baseball team can secure the most wins over. The result is a less entertaining sport.

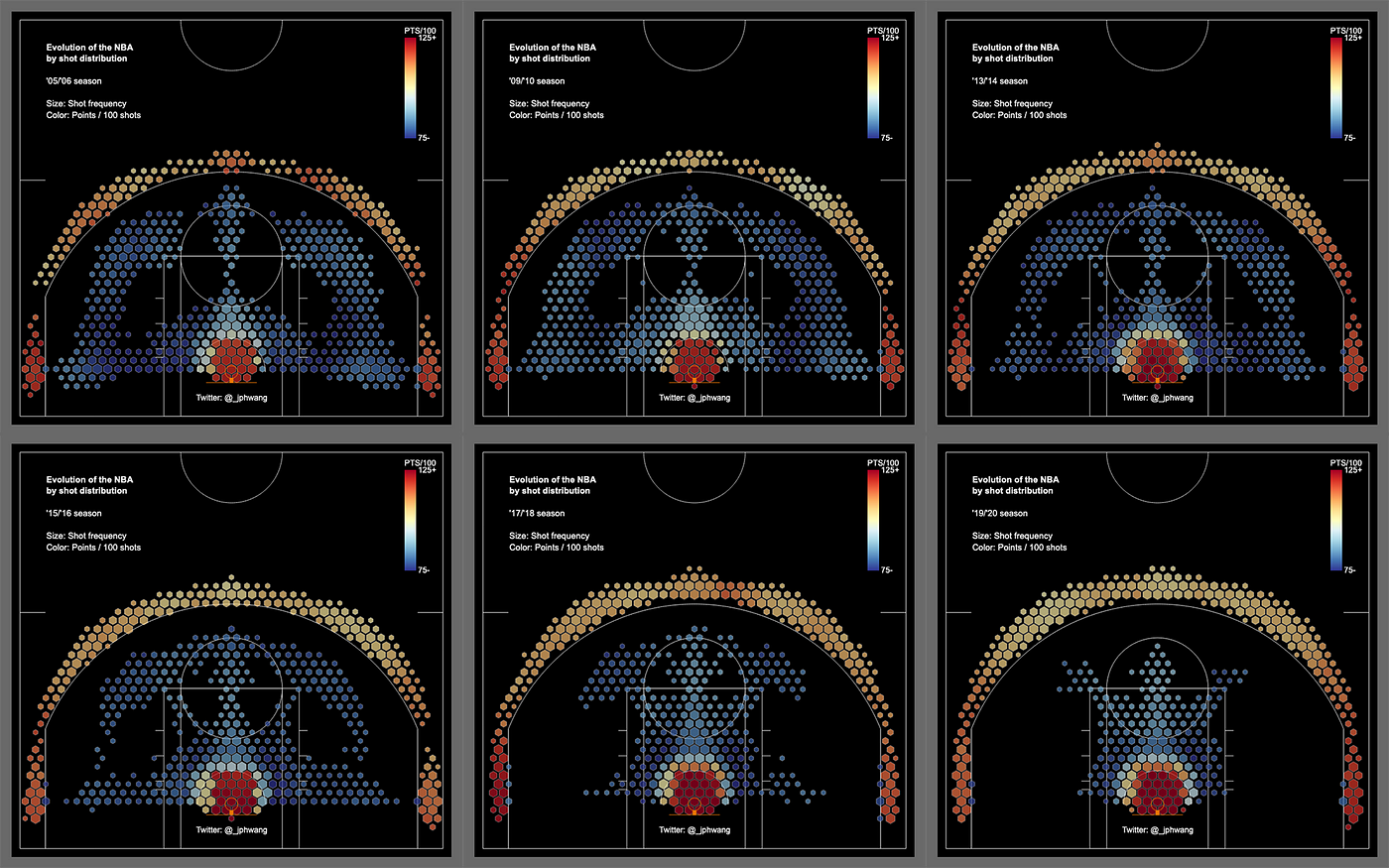

Basketball too has attracted criticism for years over its cramped and constrained modern tactics, which have produced a game where teams relentlessly pursue three pointers and layups to the detriment of other kinds of shots. This arguably results in a game that’s less fun to watch; it certainly results in a league full of teams all playing the same overall style of ball, at least at the macro level. You can see that clearly in this visualization of average NBA shot charts, which covers just 15 seasons of play, from 2005 to 2020. An entire world of two-point shots was lost as NBA shot selection was hollowed out in pursuit of maximum offensive efficiency. The fact that there are essentially no NBA teams that have consistently bucked this trend suggests that this strategy really does represent the best way to win. But some fans find the resulting play to be less engaging, which degrades the entertainment value that makes the NBA financially viable.

The sports examples are particularly apt, as they underline the fact that overoptimization does not stem from bad strategy on the parts of key players within a system. I don’t doubt that it really has been to the advantage of MLB teams to abandon the stolen base, despite the fact that the stolen base is the single coolest play in the sport, one which (unlike strikeouts or home runs) creates genuine uncertainty. I also don’t doubt that a 30% three-point shooter is often going to do more good for his team by jacking threes than by working for higher-percentage but less-valuable twos. I don’t disagree with the strategy as strategy. I dislike the outcomes that arise from teams all pursuing the same data-driven strategy when that strategy detracts from subjective enjoyment of the game. Just like guides on Mount Everest have no doubt arrived at remarkably efficient systems for getting well-paying climbers to the top. If there are not players in a system who benefit from overoptimization, then the system will not become overoptimized. The question in any case is whether anything can or should be done to change the situation and ameliorate the social costs.

There are other elements of modern life that you could potentially try to squeeze into this frame, to varying success. I suppose you could look at modern celebrity culture and its demerits as a result of overoptimization. Many have complained that the era of the great star is over, that today’s celebrities lack the transcendent quality that seemed to accrue to those of decades past. Meanwhile the celebrities themselves complain of broad lack of respect for their privacy, that they can never go anywhere without a camera in their face; the paparazzi function has been extended to anyone with a smartphone. These problems are intertwined. Many have argued, I think correctly, that modern celebrities seem less impressive because we now know too much about them. There’s too much information about their lives out there, whether it’s them giving away on Twitter which breakfast cereal they prefer or the endless amount of gossip accounts and publications constantly letting us know everything about their business. Humphrey Bogart wouldn’t have a mythical aura about him if he was sharing his lame thoughts about Game of Thrones with us on the internet. And, of course, the information-gathering process for the insatiable hunger for celebrity news - the aspect that has specifically been overoptimized - makes life less pleasant for celebrities.

In any event, though I’m sure some will see this as all too abstract or fuzzy, I’m convinced that the plight of too much information is a real thing in 21st-century life, and it’s hard to see it slowing down. So much of the internet era has been defined by unintended consequences. But we’ve opened a Pandora’s box by providing the world with immense amounts of easily-accessed information, and so of course we have many ambitious people doing everything they can to exploit it - often to the detriment of the rest of us.

This post was inadvertently rolled back to a prior draft before the last round of copyediting. The correct version has been restored.

I think over-optimization and too accessible are two important and often intertwined concepts, but they're worth teasing out some. Travel is ultimately fine, it's just less exclusive. In line with the Yglesias argument ( https://www.slowboring.com/p/restaurants-should-charge-more-forabout ) just charging people for dinner reservations, Hawaii should really have a tourist tax that's reinvested in the a range of local concerns with special attention to the native Hawaiian population.

This supply-demand mismatch is a classic problem for markets to solve. I think the trouble with efficient markets is that it becomes harder to substitute time and care for money. I think that's a problem worth thinking about, especially for things like cultural experiences where the care is part of what makes experience valuable. But travel becoming more accessible writ large is a good thing in a way the breakdown of traditional media business models is not.

Separately, your friend was making an honest living on ebay, arbitrage is part of markets clearing and all that, but it's not even a small crime that less savvy users now have a sense of the actual value of their stuff. Stores, media companies, and guidebooks add value because there's more to life than just price. They are taste makers and can help match people with the content that is a good fit for what they need or that would benefit from context and not just the content they think they want. Optimization is bad when, as in the sports case, it privileges a single goal (victory) over the larger point (fun competition).

So I think your point on the plight of too much information makes sense, but it's a few distinct problems, and, in some cases, just what greater equality looks like to those who once [benefited] from exclusivity.