The Machine God's Existence Would Insist Upon Itself, Wouldn't It?

if AI forever changes human life, you won't have to persuade anyone it's happened

Big announcement coming tomorrow morning, then a subscriber-only post on the contemporary world’s endless search for victims on Wednesday.

“Pay More Attention to AI,” reads the headline of this Ross Douthat piece, an unusually naked expression of emotional need - plaintive, wounded, yearning. It’s funny because I feel like our media has been paying attention to little else than AI for more than three years, now. Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson and sundry other general-interest pundits have periodically made these kinds of appeals, arguing that the amount of coverage devoted to AI has been insufficient, and I’m not quite sure what to do with the contention; it’s like claiming that it’s too hard to find opinions on NFL football online or that there aren’t enough newsletters where women get angry at each other for being a woman the wrong way. I would think it would go without saying that our cup runneth over, when it comes to AI. But it’s a free country!

Douthat becomes the latest to nominate this Moltbook thing as a sign of some sort of transformative moment in AI.

if you think all this is merely hype, if you’re sure the tales of discovery are mostly flimflam and what’s been discovered is a small island chain at best, I would invite you to spend a little time on Moltbook, an A.I.-generated forum where new-model A.I. agents talk to one another, debate consciousness, invent religions, strategize about concealment from humans and more.

I find this strange. We already know that LLMs can talk to each other. Any use of LLMs that produces impressively polished text in response to a prompt shouldn’t be particularly surprising. The LLMs on Moltbook are in essence feeding each other prompts that then produce responses which function as more prompts, a parlor trick people have been doing since ChatGPT went public and in fact long before. (Remember Dr. Sbaitso?)

The question is whether the systems connecting on Moltbook are actually thinking or feeling, and we know the answer to that - no, they neither think nor feel. They’re acting as next-token predictors that respond to prompts by running them through models developed through the ingestion of massive amounts of data and trained on billions of parameters, using statistical associations between tokens in their datasets to predict which next immediate token would be most likely to produce a response that seems like a plausible answer to the prompt in the eyes of a user. That the users are other LLMs doesn’t change that basic architecture; that these response strings are often superficially sophisticated doesn’t change the fact that there is no actual cognition happening, doesn’t change the fact that there is no thinking, only algorithmic pattern-matching and probabilistic token generation. Again, terms like “stochastic parrot” enrage people, but they’re accurate: however human thinking works, it does not work by ingesting impossibly large datasets, generating immense statistically associative relationship patterns and probabilities, and then spitting out responses that are generated one token at the time, so that we don’t know what the last word in a sentence (or the third or fifth) will be while we’re saying the first.

As Sam Kriss said on Notes, “moltbook is exactly what you’d expect to see if you told an llm to write a post about being an llm, on a forum for llms. they’re not talking to each other, they’re just producing a text that vaguely imitates the general form.” Please note that this is not primitivism or denialism or any such thing, but rather just a reminder of how LLMs actually work. They’re not thinking. They’re pattern matching, performing an exceptionally complex (and inefficient) autocomplete exercise. I think people have gotten really invested in this whole Moltbook phenomenon because the weirdness of LLMs performing this way invites the kind of mysterianism into which irresponsible fantasies can be poured. Yes, it looks weird, apparently weird enough for people to convince themselves that in ten years they’ll be living in the off-world colonies instead of doing what they’ll really be doing, which is wanting things they can’t have, experiencing adult life as a vanilla-and-chocolate swirl ice cream cone of contentment and disappointment, and grumbling as they drag the trash cans to the curb in the rain. Access the most ruthlessly pragmatic part of yourself and ask, which is the future? Moltbook? Or the all-consuming maw that is the mundane in adult life, the relentless regression into the ordinary?

Of course, you can always say “wait until next year!,” and Douthat’s analogy - that our present moment with LLMs is similar to the discovery of the New World, the entire vast and fertile landmass of the Western Hemisphere - depends on this projection, because on some level he’s aware that a bunch of LLMs crowdsourcing the creation of an AI social network (which, due to how LLMs function, amounts to a facsimile of what most people think an AI social network would look like) is not useful or practical or ultimately important. And, sure, who knows. Maybe tomorrow AI will end death and do some of the other things we’ve been promised. But this is the same place we’ve been in year after year, now, with AI maximalists still telling us what AI is going to do instead of showing us what AI can do now. As I’ve been telling you, I decline. 2026 is the year where I don’t want to hear another word about what you think AI is going to do. I only want to see proof of what AI is actually, genuinely doing, now, today.

Once again, I ask you to consider whether the yearning for AI revolutions that we keep seeing in guys like Douthat are the product of them… being guys like Douthat. Which is to say, endearing daydreamy types, the kids who spent every bus ride imagining they were on a flying carpet, the kids who came up with their own RPGs in the margins of their algebra notebooks. I mean, Douthat’s been writing and talking about JRR Tolkein his entire career, right? He’s written a serialized fantasy novel that’s genuinely well-regarded. He constantly injects modern politics with comparisons to distant history, apparently feeling like this injection can bring a sense of nobility and meaning that our grubby modern reality rarely provides. In fact I think you can argue that at the core of Douthat’s oeuvre has been not his mannered vision of conservatism nor his convert’s zeal for Catholicism or even his permanent discomfort in both his explicit ideological environs and his adopted liberal homes, but rather longing.

Longing permeates Douthat’s self-expression. His first book Privilege is about a young man who arrives at Harvard and longs for the world of genteel citizen-scholars he’s imagined, instead of the frivolous and grasping little selfish-interest machines he encounters on campus. His book The Deep Places is about longing, yes longing to be healthy from a mysterious chronic illness but also about the power of that longing to overwhelm the rational mind he’s spent a lifetime cultivating. His most recent book, Believe, takes his own longing for transcendent meaning and projects it out onto the world around him, hoping to find in the rest of us the same restless need for truth that haunts him, in what I find a charming and sad bid to feel less lonely. And I think you can find his permanently uncomfortable position as a house conservative in the temple of genteel American liberalism to represent a kind of longing as well; I think Douthat is entirely aware of how his role at the NYT ultimately fails both his very real root conservatism and his revulsion towards the excess and ugliness of the modern American right-wing, but he’s content to work in that space as an expression of his longing for a different, better American politics.

Not to pick on Douthat. I guarantee you that Ezra Klein spent a lot of time as a kid convincing himself that the hoverboards from Back to the Future II were real, you know what I mean? I think almost all of the most prominent AI boosters in our media are That Kind of Guy. And it’s fine. It’s just another example of a great challenge almost none of us ever really overcomes, the challenge to understand our own motives.

Here’s the point, folks: the motte and bailey has to stop. The constant two-step is exhausting. They make absurdly outsized claims about what AI is and does or will do; when it’s pointed out that these tools are at present very limited, certainly relative to the hype, the response is some version of “Well let’s be realistic now!” These are transformative technologies, but when we ask to see the transformation we’re accused of asking for too much. I can’t stand it anymore. The most capable consumer LLM has such little grasp of the nature of reality that it imagines that a high-security psychiatric hospital would have a pool hall for patients in the basement of a nonexistent building. And yet that very tool, that specific LLM, is routinely predicted to imminently take over a majority of all human intellectual and clerical and creative work. I’m allowed to have doubts about this vision! The problem is not disagreements about what the future of AI will be or even in assessing what AI can do currently. The problem is constantly searching for the most outsized rhetoric possible to describe the potential of AI and then, when challenged, hustling back to talk of being realistic about what we can expect.

I keep bringing up existing transformative technology, like indoor plumbing, in order to establish a baseline of what actually transformative technology can do. If we suddenly lost indoor plumbing no one would find it necessary to write wounded, defensive essays about how important indoor plumbing is. If automobile technology disappeared off the face of the earth tomorrow, nobody would feel compelled to write forty-tweet Twitter threads about how we don’t really fully grasp how important cars are. Transformative technology insists upon itself, its affordances are so obvious and powerful and pervasive that they’re beyond the need for persuasion. People at the commanding heights of our society have insisted that LLMs are more important than fire or electricity, a bigger deal than the Industrial Revolution. Well, allow me to ask you: if we somehow lost access to fire and electricity, if the Industrial Revolution was rolled back by magic, would anybody feel moved to write defensive essays in The New York Times about why they’re so meaningful? I would contend that no one would bother; no one would feel like they needed to. Let that wisdom guide you now.

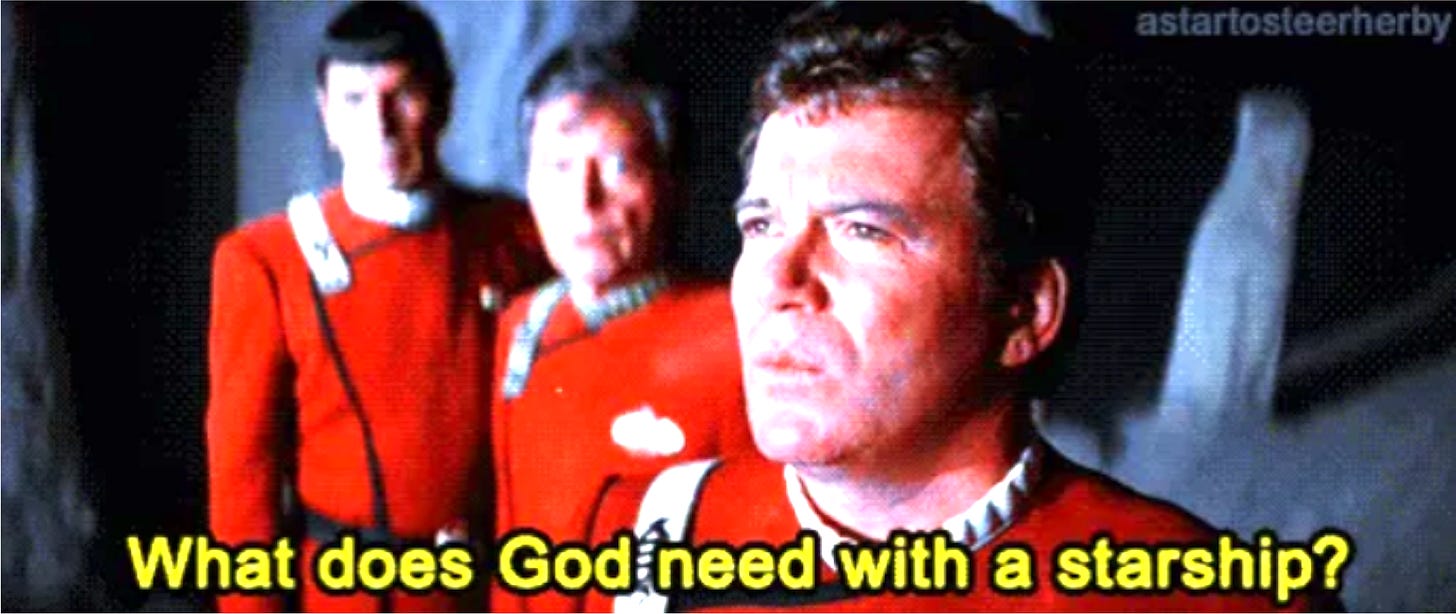

If this really is the time of the machine god, the machine god will assert itself the way a god can and no one will have to argue for its divinity. That’s kind of the whole point of being a god. Right?

I have no particular knowledge of what is coming but your argument is flawed in a way that seems really obvious: why if we are just in the early stages?

The automobile absolutely did not insist on its own transformative power in 1880. It took decades before it became clear it was going to revolutionize personal transport. Netflix’s vision of streaming, which they had all the way back in 2000 or so, did not seem like it was going to upend the entire movie/TV model while I was still a 14 year old buying the DVD for Idle Hands. The refrigerator had serious competition from the ice box and general inertia.

You may be 100% right about AI’s limitations and future, Freddie. But it’s weird to say “This tech isn’t going to be transformative or revolutionary because it’s not right now! DUNK!”

I find the reactions to moltbook incredibly bizarre. The training set for these LLM's is the corpus of text on the internet, a huge body of which comes from reddit. Recreating reddit patter in infinite quantity is the most basic, trivial function for this kind of technology. How do people not (pun intended) grok that?