the lee of the stone

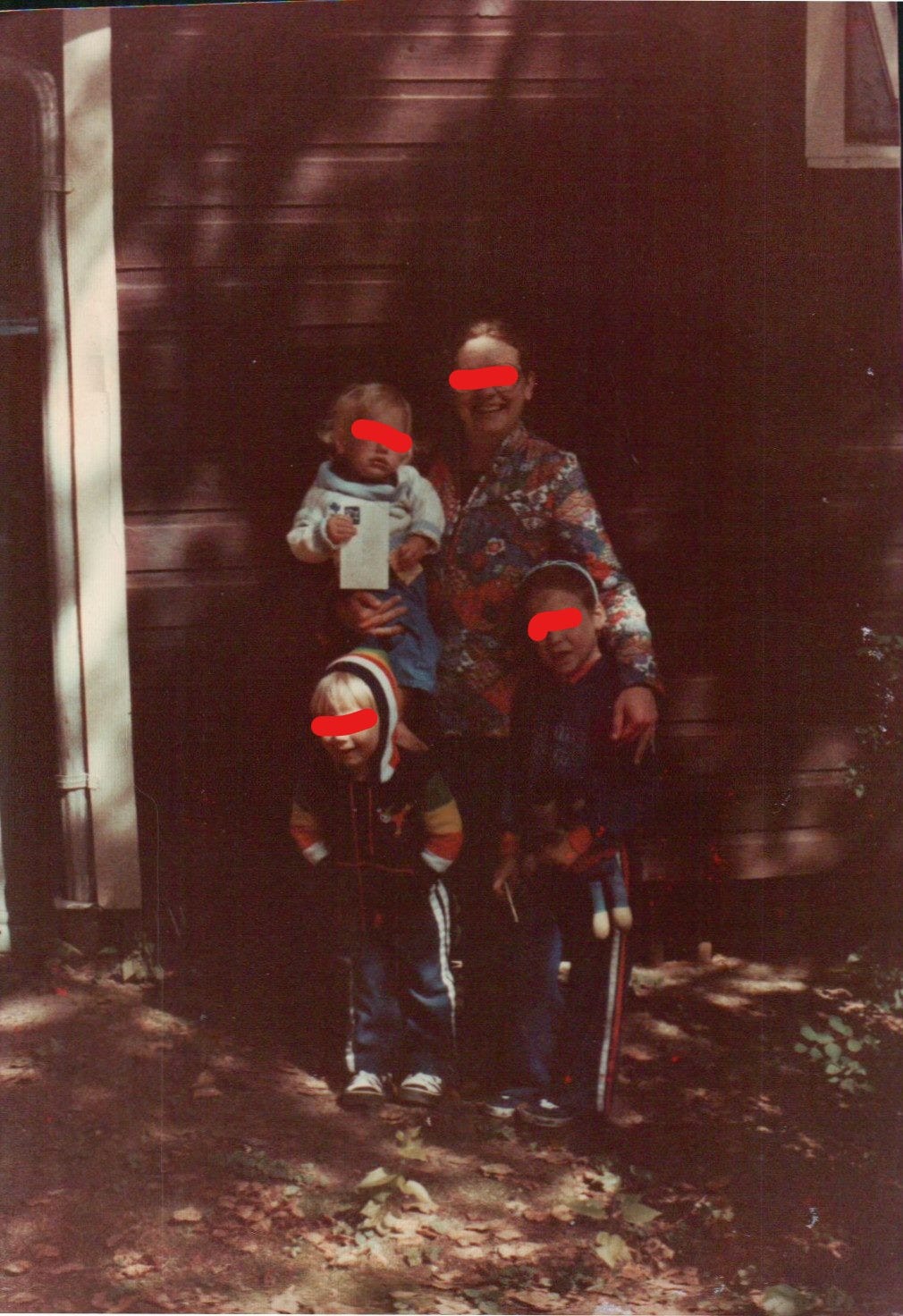

To the back and on one side were fields and so too across the street and as you faced the house to the lefthand side an old orchard of rotting crabapples and once I had tried to eat one, mealy and bug-ridden, its sourness less surprising than how it liquified immediately and stained my chin. We had two beautiful red Irish setters, Molly and her daughter Doogan, and they would wander for miles until he would come shuffling out past the rock wall he had built to mark our property line and would stand gazing out across the field up to the woods for awhile, until he would bellow out their names in that deep cracked voice of his like a cello string that threatened to snap at any time, and from backwoods and sewer tunnels they would come, carrying burrs and mud with them in their auburn fur. He grew weed in the backyard and there were raspberry bushes on the boundary of the property and a single sickly vine whose grapes tasted like liquid magic and we children would roam our little world like hermit crabs on a beach, never moving in the direction we seemed to. When Doogan died he never told us. By then those conversations had become too hard. I think he just couldn’t say it.

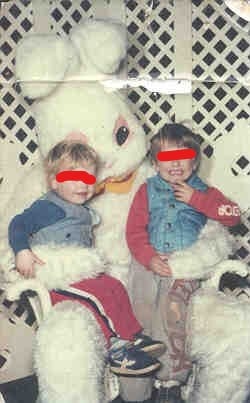

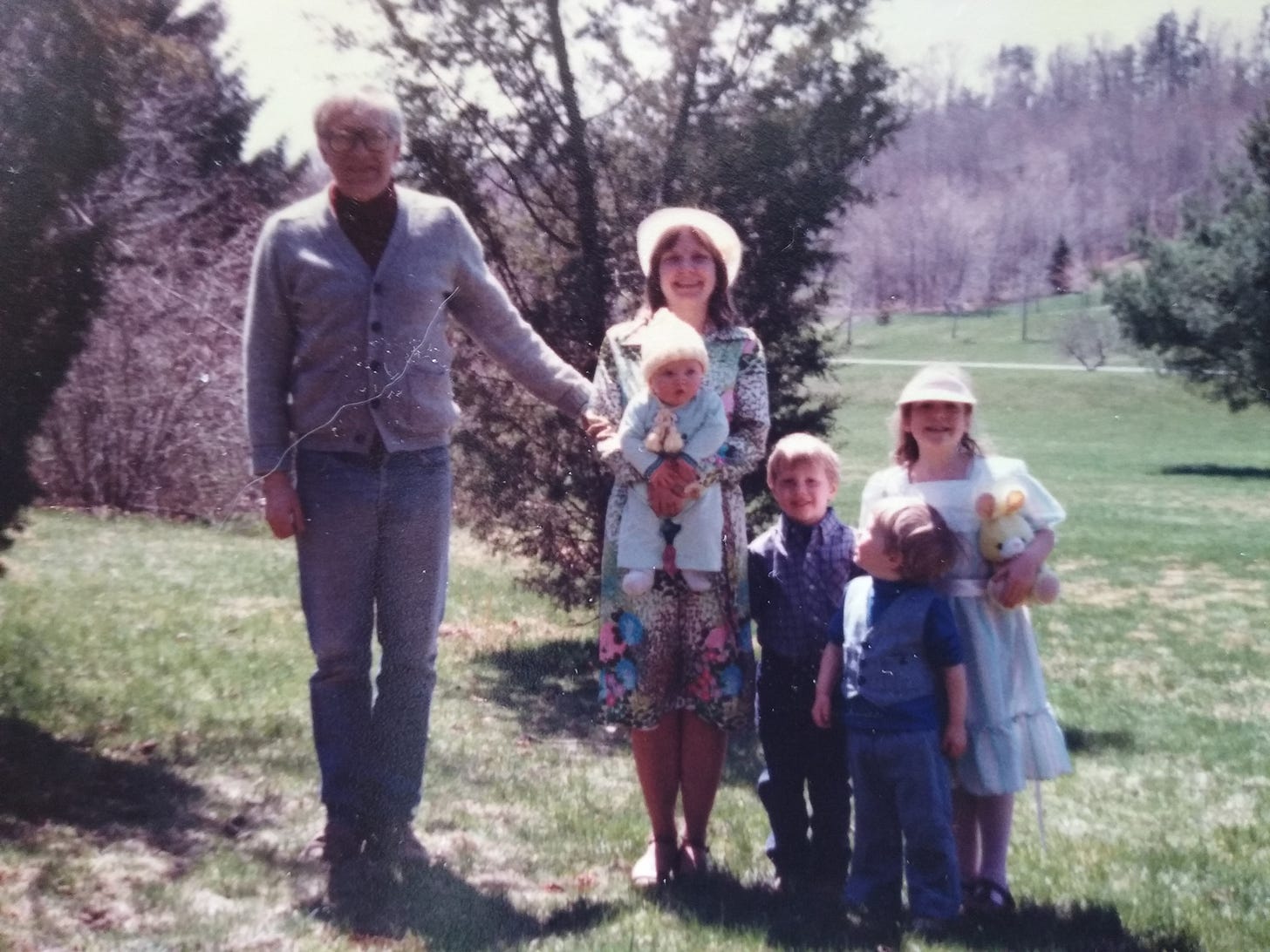

She had left what she could no longer bear in Florida and brought my beautiful 4 year old sister back to Connecticut and turned up at her ex-boyfriend’s little white house and told him “I need you to look after us for awhile.” And they just never left. That is how we came to be.

I went to see her in the hospital. They had wrapped her eyes in some sort of covering; later I came to realize it had to have been because, being brain dead, her eyes would have been hollow and vacant, staring across the room, certain to catch the glance of those who did not want to see what was left of their mother. I know it can't be right, but in my memory the wrapping is the texture of paper, white paper, butcher's paper. All I knew at the time was that nothing to me could have been more distant than her docile body. She had been a lithe creature, physical and antsy, and the motionless object before me should have told me all I needed to know, but I was still somehow surprised when he came home a couple days later to tell us she was dead. She complained of a headache on a Wednesday afternoon; by Saturday night she was gone. Our family friend Jane wept as she clutched my sagging body against her. I broke free and sat in the middle of the stairway so I could be on neither floor, determined to spend the rest of my life in that not-place where there were no mothers and no doctors to wrap their eyes in paper.

She had saved the local arboretum from development and they named it after her. In high school when I could not stand to be in that house with [her] I would go there and stand under a dogwood tree and picture myself as branches that refused to bloom.

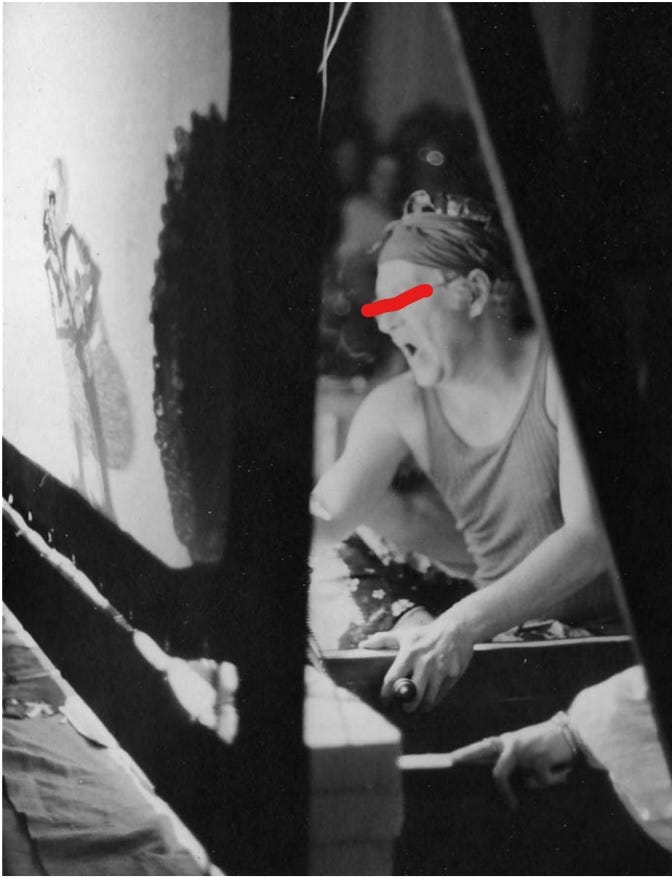

He did his best. He was loving and creaky and defiant and tender. He had a big belly for grabbing and he cried over movies and at night when I would find him by the rock where Molly was buried he would be gazing out into the darkness looking for something in the sky, far away. He was soft and sensitive and made of fire and so he would exhort his students to lie on the floor and feel themselves be burned as Artaud had commanded. He was unsparing against sentimental dishonesty. He radiated a kind of crippled integrity and when he felt like it, tottering slightly on his feet, dressed in a stained shirt and shoeless, he could render a vice principal or cop speechless with the brittle iron in his voice, his presence. As a father he was great at the big stuff, the unconditional love, and terrible at the small things, and it is the small things that scar you for life; to this day I wear the proof on my teeth. He did not forget and would not let us forget our middle class advantages even in the periods of our deepest grief. He spent his nights locked away with a bottle of vodka and his room had once been a garage and the path to it meant bare child feet on a cold stone floor and then you were confronted with the decision whether to knock, the locked door in front of you and the sound of him softly singing along to music he hadn’t bothered to play. But if you did knock, he would hug you and you felt it in your bones. He was gentle towards us, and he was wise, and he had lived through it all, and when I crawl outside of myself for long enough to briefly experience a quiet mind, it's his voice I hear.

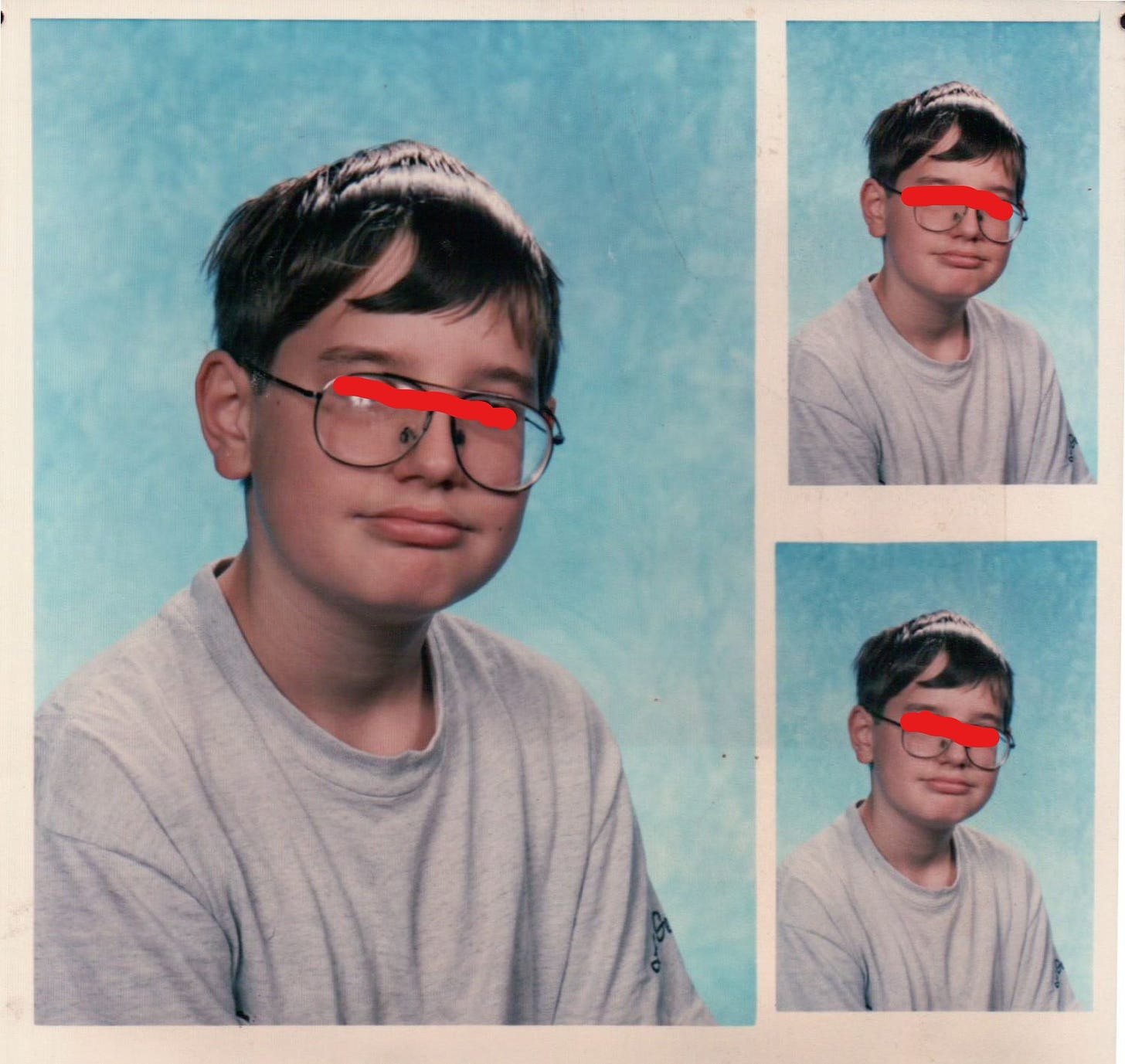

Eventually [she] was there. It didn't work, had never worked, but then he was ill and had been ill and he was dying and something had to be done. Where would we go? The daily unhappiness of the failed blended family was the bitter distraction from watching him fall away, drop drop drop. Screaming fights and broken glass but always, in the center of it all, the sad spectacle of someone trying not to die. He was 45 the day I was born. By the time I was a teenager he was weathered, wise, scarred from ancient track marks, big as a house, depressed and infirm. He went to church and sang in his crackle. He groused and lamented. He tried and failed to hide from us to smoke his joints. Unlike with my mother there were to be no surprises here; disease was written on his face, in his eyes, his sagging body. I can date a picture of him from the last couple of years by studying his jaundice. We went on a trip when I was 13, just him and me, and at the airport they insisted he use a wheelchair and I trudged along behind him wishing that I could disintegrate everyone whose path we crossed. The flight attendant said “your grandfather” three times and I hoped the plane would lose altitude, yaw lazily through the lower atmosphere, then slip gracefully into the sea.

The insurance company shipped him across country to die at Cedars Sinai. My little brother endured a year in hell in a Los Angeles middle school. My older brother and I lived alone in our house and went to high school, telling the administration there we were being looked after by an uncle who didn't exist. My brother handled the money and drove the car and at lunch I would cross from my part of the cafe to his and he would extract his comically large wallet and slip me two dollars, sometimes a five, and I would dine out on grilled cheese and Choco Tacos as the cafeteria would hoot directionless around me like the crowd at a baseball game and it comforted me. Beyond paying for lunch at school I don’t know that I spent more than $50 combined on anything that entire year. I just ran and read and watched MST3K on Sunday mornings on my little woodpaneled TV and studied the floor when grownups spoke to me and I would think of him in his sickness and wonder if he had already dissolved away into mist and they were all sparing my feelings. But we’d have our friends over and they would sit on armchairs and drink lemonade before running off into the cool summer night. What I’m saying is that for that year we were free.

When he lay dying in the hospital I came to visit him for the last time. Unlike her he twitched and spasmed in the hospital bed; some sort of wires emerged from his neck and where they did his skin was dark purple. He was dressed in a too-small robe, and they had given him a hypoallergenic blanket made of plastic, and in his delirium and weakness as he saw me approach he feebly tried to move the blanket to cover himself and preserve his dignity in front of his 15-year old son. And I knew even then that memory of all that was fierce and flawed in that fierce and flawed man would slowly be lost, and in my mind all I would have left was that feeble motion, that plastic blanket. Today at least I still have the creak of shoe leather in his voice, the smell of alcohol, and infinite love. Of my mother I have only fantasies I choose to call memory.

I was to fly back to Connecticut. Sophomore year was the big state standardized tests, brand new ones. I was in the bottom quarter of my class rank but somehow the guidance counselor thought it was essential. We had already discussed that I would go back home, he and I, but some combination of the drugs and the cancer had left him delirious and fading and when I told him I was leaving he cried like a child and asked me not to go. It would have meant everything to him for me to stay and it meant nothing at all for me to fly back to high school and the pitying half-hugs of teachers. And I squeezed his hand and told him I loved him and for some reason I left anyway, to take a test no one had heard of in a high school career that gave me nothing, and I have turned this over in my mind every day of my life for 24 years, that he wept and in his last days asked me for something I could have given and yet I walked out mutely for reasons I couldn’t define. The next time he appeared in my life he was my sister’s shaking voice over the phone. That night I lay curled up under a blanket and thought of him eating mango, smoking kreteks, tracing shaking patterns with his hands, speaking Bahasa to old friends long into the night as I pretended to sleep in the heavy island air.

After that came the days with [her], and about them I will not speak.

We emerged. When I left that house I took nothing with me. I can’t remember if I had ever intended to go back for my things, but either way I never did. Anyway [she] had taken most of what I wanted. One day when I was at school [she] had gone into my room and found my father’s old leather jacket and stolen it and given it to her brother. And the old house, which we had been told had been for us, was mysteriously sold, and the money went who knows where. All of his things were gone. I try not to think about it now. My sister and her husband uprooted their lives to come and take care of my younger brother. When time had passed and all the endless legal and financial and material connections with [her] were dissolved, it was time to look up and around at a young adulthood I had no capacity to face. My grades had been terrible. I couldn't get into college. Sometimes I had a little money and sometimes I didn’t. I found I could not ask for help and I wouldn’t have known who to ask anyway. I felt like someone should at least realize that something out of order had occurred, should at least say “something has happened here,” but the world spun on. And the guilt, it just worked its way into everything I was until I could physically feel it, the punishing guilt that pressed against my temples and the back of my eyes.

Then when I was 20 I lost my mind. I had rented a terrible $600 apartment with paper-thin walls and for months I would curl up in the fetal position on the carpeted floor and squeeze my fists until they ached and then, one day, I didn’t want that anymore, in fact I wanted to drive hundreds of miles in the middle of the night, the same circle of highway for hours or to Maine to walk with bare feet on wet sand in November. I would go down by the river and throw sticks into the current and count how long it took for them to disappear out of sight and as I did I would trod the dirt around me. Suddenly I could not move fast enough; suddenly I was of world historic importance and they were coming for me. It took over my brain over the course of months, a cat that lazily stalked my composure with unhurried diffidence until, one day, it pounced, and then I was fogging the glass of the window of a cop car. They try to take you back to make it easier, speaking slowly to you, confining your world to Jell-O and crayons, giving you drugs that blunt your mind until you are childlike again, but I did not want to go part of the way back, only all the way back to the womb or else into the uncluttered future. “You must always keep taking your medicine,” they told me, “and now let’s talk about your childhood.” I could not bear to tell my siblings, who had lived through so much so recently, which meant I could not tell anyone. When it was time to leave I just walked away. I ambled down to Main Street in my hometown and saw it with naked and narcotized eyes. The pills tasted like chalk and clattered like teeth when I poured them down the sink.

Then came years that squished together and expanded out again, back and forth like an accordion. I learned about 9/11 from a bored ophthalmologist as he switched between lenses in front of my face, “better one? better two? better one? better two?” I went to community college and then the local commuter school; I developed film in a dark room a year before they closed it down for good, then dove into anti-Iraq war activism with both feet and learned the hard way the price you could pay for being right. I would drive up to Boston to cure my loneliness and cling to friends, and we sanctified it all with alcohol. I got my dog Miles, and for thirteen years he was my own. A heroically misguided semester in Hawaii, hours spent staring at water and inhaling chlorine, a quick tour in Europe, drinking and drugging and fucking my way across Chicago, girlfriends I adored and did not understand, friends who sustained me, a trip to the great parks out west, years doing nothing but trawling Craigslist for gigs, drinking and fucking my way through grad school, coming to New York, making and losing friends, being enchanted and watching myself slowly coming unglued. Sprinkled throughout it all was reading, music, sex, friendship, sometimes pills, my dog and my cat Suavi, beer, forever hopscotching right by the edge of falling into the future I desperately wanted - a home, a wife, a child perhaps. And every once in awhile they would tell me I had to surrender my belt and shoelaces. Then, the hard stop, and no more running, and life was pills. All was pills. And here we are.

And now I am performing the secular sacrament: I am sharing my trauma. I don’t know why. Some lonely impulse I’ll regret. I hope it’s entertaining. They talk a lot about trauma today, and I wish I had something useful to say. I cannot tell you how to be traumatized. I can’t tell you how to do anything at all. If you are compelled to share your trauma, as I apparently am, you are free to do and say whatever you would like. I hope it serves you in whatever way you want it to.

I will tell you my experience, in case it is useful to you. And my experience is that there is no upside to trauma, no pleasant narrative of recovery after the fall, no fuller self to be gained, no wisdom waiting for you at the end of the trail. Trauma does not make you who you are, other than perhaps those things that are ugliest and least true about you. Trauma is not beautiful. Trauma is not regal or enlightening. Trauma does not have a narrative arc. Trauma is not a growth opportunity. Trauma is not ennobling. Trauma does not give you new reserves of strength. Trauma takes the reserves you have and drains them like a butcher desanguinates a pig. Trauma does not leave you looking picturesque as you cry in the rain. Trauma leaves you collapsed in public, screaming at your friends, sputtering in an ugly mass of self-hatred and impotence. Trauma hurts you and then it hurts the people around you in turn. Trauma is not interesting. Trauma is in fact very boring. You do not hang as a chrysalis within your trauma until you emerge some impossibly beautiful creature. Trauma makes you worse. Trauma fucks you up, and afterwards you are fucked up.

So if trauma breaks you consider allowing yourself to just be broken. Know that you could be broken again, worse and more easily next time. Go to therapy, take the pills, get the help. But don’t force yourself to see your trauma as a journey to peace. It will hurt and it will hurt and it will hurt and eventually it will hurt less, and maybe if you’re lucky somedays you’ll forget. And if you are fortunate enough to get over it, as I surely have not, you must let it go completely. You and I must no longer cling to it but let it slowly leave our lives like air slowly escapes from a withering balloon. That’s the end, that’s it. That’s all there is.

I walk in Prospect Park every day now. In spring the trees flower and little day care classes wander around with all the toddlers clutching the same walking rope, knuckles white like they fear that if they let go they would float off into the clouds like Chinese lanterns. The swans swim lazily by, beautiful and perpetually enraged, and the homeless pitch tents deep in the woods, looking for thick underbrush in which to hide. There are dogs that remind me of my dog and parents that remind me of my parents but best of all there is nothing that reminds me of me. And in the quiet corners I can stand motionless like a tree and pretend that if I can slow my heart until it stops she will appear before me and with the soft touch of her palm save me forever from myself, liberate the small worthwhile kernel of my heart from this life I do not recognize, this broken mind, this drug-diseased body. But the lithium makes my hands shake and she will not come. Instead there is only an aging mental patient who would prefer to be anything else than himself, standing stock still, hoping to be lifted up and feathered away by a woman who’s been dead for thirty years, and the beautiful young people in the park orbit all around me composed and unafraid.

Now, though. Now another woman has come into my life and for reasons that are mysterious and remote she has looked at all of this and said, “I would like to be with him.” She listens to me quietly as I evacuate my heart and with tender patience draws me close and tells me she will be the one who will not go. She too has memories of a childhood lived in pain, and hers have made her compassionate and free. And now when I reach out in the night I am reaching for her, for the creature that she is, with her wise sad face and her kindness, her grace. Perhaps now there is something to look forward to. Perhaps it is time to realize that this is good enough. Perhaps I have found myself at last on the other side of the rock, the side protected from the wind, and at last life’s depravations will blow harmlessly over my head and spin out over the plains where they can do no harm, and leave me alone. She is the rock. 진심으로 사랑해.

A year ago I was rotting away alone in this same apartment, waiting for the axe to fall at work, broke and directionless and afraid in a world that had suddenly locked all of its doors. I must have worn away the hardwood floors from pacing the same circles, pretending that the problem with my life was the virus. Now, after nine months of unemployment, suddenly this new project has appeared, and now there is money enough. And now too there is her and her gentleness and her endless brown eyes. My family draws breath, and beyond that there is little to say, only that we’ve grown by two nieces and a sister-in-law and, soon enough, a wife, and thus are so much more powerful than you can imagine, and we all hold fast to each other, and only we know what we have been through, and I am proud. I always knew we would shake off the grubby clutches of what the world had made for us, and I know looking forward that we will survive and, like some great owl, ascend above the world and from the safety of that altitude comprehend it with all-seeing eyes.