Study of the Week: When It Comes to Student Satisfaction, Faculty Matter Most

In an excellent piece from years back arguing against the endless push for online-only college education, Williams College President Adam Falk wrote:

At Williams College, where I work, we’ve analyzed which educational inputs best predict progress in these deeper aspects of student learning. The answer is unambiguous: By far, the factor that correlates most highly with gains in these skills is the amount of personal contact a student has with professors. Not virtual contact, but interaction with real, live human beings, whether in the classroom, or in faculty offices, or in the dining halls. Nothing else—not the details of the curriculum, not the choice of major, not the student’s GPA—predicts self-reported gains in these critical capacities nearly as well as how much time a student spent with professors.

I was always intrigued by this, and it certainly matched with my experience as both a student and instructor - that what really makes a difference to individual college students is meaningful interaction with faculty. I have always wanted the ability to share this impression in a persuasive way. But Falk was making reference to internal research at one small college, and I had no way to responsibly discuss those findings. We just didn't have the research to back it up.

But we do now, and we have for a couple years, and that research is our Study of the Week.

The Gallup-Purdue Index came together while I was getting my doctorate at the school. (Humorously, it was always referred to as the Purdue-Gallup Index there and no one would ever make note of the discrepancy.) It's the biggest and highest-quality survey of post-graduate satisfaction with one's collegiate education ever done, with about 30,000 responses in both 2014 and 2015. The survey is nationally representative across different educational and demographic groups. That might not leap out at you, but understand that in this kind of longitudinal survey data, that's all very impressive. It's incredibly difficult to get this a good response rate in that kind of alumni research. For example, a division of my current institution sent an alumni survey out seeking some simple information on post-college outcomes. They restricted their call only to those who they had contact information known to be less than two years old and who had had some form of interaction with the university in that span. Their response rate was something like 3%. That's not at all unusual. The Gallup-Purdue Index had an advantage: they had the resources necessary to provide incentives for participants to complete the survey.

Why student satisfaction and not, say, income or unemployment rate? To the credit of the researchers, they wanted to use a deeper concept of the value of college than just pecuniary. Treating college as a simple dollars-and-cents investment happens in ed talk all the time - take this piece by Derek Thompson on the value of elite schools, relative to others, once you control for student ability effects. (There isn't much.) I get why Thompson frames it this way, but this sort of thinking inevitably degrades the humanistic values on which college was built. It also unfairly discounts the value of the humanities and arts, which often attract precisely the kinds of students who are most likely to choose non-financial reward over financial. There's still a lot of value talk in there - this was, it's worth mentioning, a Mitch Daniels-influenced project, and Mitch is as corporate as higher ed gets - but I'll take it as an antidote to Anthony Carnevale-style obsession with financial outcomes.

So what do the researchers find? To begin with: from the perspective of student satisfaction, American colleges and universities are doing a pretty good job - unless they're for-profit schools.

alumni rated on a five-point scale whether they agreed their education was worth the cost. Given that many families invest heavily in higher education for their children, there should be little doubt about its value. However, only half of graduates overall (50%) were unequivocally positive in their response, giving the statement a 5 rating on the scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Another 27% rated their agreement at 4, while 23% gave it a 3 rating or less.

This figure varies only slightly between alumni of public universities (52%) and alumni of private nonprofit universities (47%), but it drops sharply to 26% among graduates of private for-profit universities. Alumni from for-profit schools are disproportionately minorities or first-generation college students and are substantially more likely than those from public or private nonprofit schools to have taken out $25,000 or more in student loans.

This tracks with a broader sense I've cultivated for years, particularly in assembling my dissertation research on standardized testing of college learning, that the common perception that we are in some sort of college quality crisis is incorrect. I suspect that the average college graduate, as opposed to student, learns a great deal and goes on to do OK. The problems, financial and otherwise, mostly afflict the students we have to sadly label "some college" - those who have taken on student loan debt for degrees that they then don't complete. They are a tragic case and, like student loan borrowers writ large, they desperately need government-provided financial relief.

(Incidentally, this dynamic where people think there's a crisis with colleges writ large but rate their own school highly happens with parents and public schools too.)

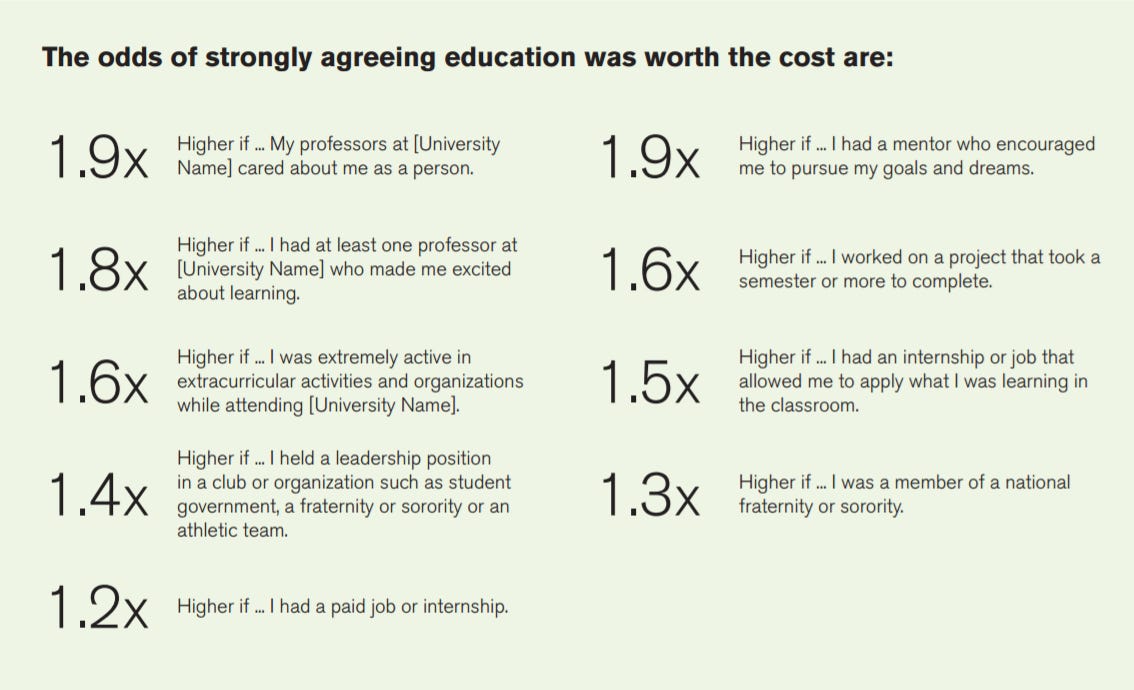

Most importantly than the overall quality findings, this research tells us what ought to have always been clear: that faculty, and the ability for faculty to form meaningful relationships with students, are the most important part of a satisfying education. Check it out.

The three strongest predictors of seeing your college education as worth the cost are about faculty. And not just about faculty in general, but about relationships with faculty, the ability to have meaningful interactions with them.

There are certainly conclusions you could draw from this that not all faculty would like. In particular, this would lend credence to those who think that faculty at research universities are too disconnected from their students because of the drive for prestige and the pressure to publish. But two conclusions that most any faculty members could get on board with are these: one, that the adjunctification of the American university cuts directly against the interests of students, and two, that online-only or online-dominant education cuts students out of the most important aspect of college.

The all-adjunct teaching corps is bad not because adjuncts are bad educators or because they don't care; many adjuncts are incredibly skilled teachers who care deeply for their students. Rather, adjuncts must teach so much, and balance such hectic schedules, that reaching out to students personally in this way is just not possible. At CUNY, I believe the rule is that adjuncts can work three classes on one campus and two at another. I know it's difficult for people who don't teach to understand how much work and time a college class takes up, but 5 classes in a semester is a ton. (Even at my most efficient, as a teacher I could never spend less than about three hours out of class for every one hour in class, between lesson planning, logistics, and grading.) Add to that having to go from, say, Hostos Community College in the Bronx to Brooklyn College here in south Brooklyn, and you can get a sense of the schedule constraints. Many adjuncts don't even have an office space to meet students in outside of class. How could they be expected to form these essential relationships, then?

Online courses, meanwhile, cut the face-to-face interaction entirely. Can those relationships still be fostered? I'm sure it's not impossible, but I'm also sure that it's much, much harder. People have expressed confusion to me over my skepticism towards online classes for a long time, but I'm confused by their confusion. Teaching is a social activitiy. There seems to be a large number of aspects of face-to-face teaching that we don't even attempt to replicate in online spaces. As both a teacher and a student, I have found my online courses to be deeply alienating, lacking any of the organic sense of mutual commitment that is essential to good pedagogy. My biggest concern is the lack of human accountability in online education. As an educator, I often felt that my first and most important role was not as a dispenser of information, much less as an evaluator of progress, but as a human face - one that brought with it the sort of sympathetic responsibility that underwrites so much of social life. What I could offer to students was support, yes, but of a certain kind: the support that implies reciprocity, the support that comes packaged with the expectation that the student would then recognize his or her commitment to doing the work. Not for me, but for the project of education, for the process.

I know that this is all the sort of airy talk that a lot of policy and technology types wave away. But in a completely grounded and pragmatic sense, in my own teaching the students who did best were those who demonstrated a sense of personal accountability to me and my course. They were the ones who realized that a class is an agreement between two people, teacher and student, and that each owed something to the other. How could I foster that if I never saw anything else beyond text and numbers on a screen? And note too that the financial motivation for online courses is often put in stark terms: you can dramatically upscale the number of students in an online course per instructor. Well, you can't dramatically upscale a teacher's attention, and there is no digital substitute for personal connection.

Does this mean there's no place for online courses? No. In big lecture hall-style classes, there isn't a lot of mutual accountability and social interaction, either. I don't doubt that online courses can be part of a strong education. But I feel very bad for any student who is forced to go through college without repeated and extended opportunities for faculty mentorship - particular students who aren't among the top high school graduates, given the durable finding that the students who do best in online courses are those who need the least help, likely because they already have the soft skills so many in the policy world take for granted.

The contemporary university is under enormous pressures, external and internal. We ask it for all sorts of things that cut against each other - educate more students, but be more selective; keep standards high, but graduate a higher percentage; move students through the system more cheaply, more quickly, and with higher quality. Meanwhile we lack a healthy job market for those who don't have a college education, making the pressure only more intense. There are no magic bullets for this situation. But it is remarkable that so little of our attempts to make progress involve recognizing that the teachers are the heart of any institution of learning. We've systematically devalued the profession, doing everything we can to replace experienced, full-time, career academics with cheaper alternatives. Perhaps it's time to listen to our intuition and to our alumni and begin to rebuild the professoriate, the ones who will ultimately shepherd our students to graduation. If we're going to invest in college, let's start there.