Sneer if You'd Like, But Engineered Solutions Are a Lot More Plausible Than Behavioral Change in 2022

the latest installment in "what exactly do you have to laugh about"

I was intrigued, in a kind of sci fi way, with this piece by Jason M. Barr, advocating for a major extension of Manhattan to be built out into the harbor. While wildly expensive, the process isn’t remotely a tough pull technologically or in terms of engineering. (You can look at a map of Boston’s original coastline and see how much of the local waterways were claimed for land, and that accomplished with dramatically more primitive technology than we have now.)

As for the why, well, people really like New York and want to be here, but there’s limited land and a lot of veto points against sensible building. Anyone looking at Manhattan rents can understand why dramatic interventions might be necessary. Barr also suggests that such an extension could serve as protection against climate change-driven storm surges. Seems intriguing to me. Still, the piece quickly became the daily “thing everybody sneers at,” a sacred status in certain clines. I really don't get the derision. Sure, Barr’s proposal is intentionally provocative and knowingly quixotic. That doesn’t make it any less likely than other approaches to solving the problems it identifies. Do you think it's more likely that the comfortable people that own New York are going to change their behavior? Because if you do, well, I think you’re naïve.

I have become, against my will, quite fatalistic about solutions to social problems that require any kind of widespread public buy-in. And though I’m somewhat antagonistic to the cultures that tend to advocate for engineering solutions, such as those of Silicon Valley or the finance industry, I feel drawn to such solutions because social change seems so impossible. We’re riven by partisanship and internet-fueled culture war, we don’t trust institutions or each other, and in my anecdotal experience the rise of casual nihilism - the bitter, I’m-joking-but-not-really insistence that everything is broken and can’t be fixed - is rising fast. All of that in a winner-take-all socioeconomic system that incentivizes being selfish. It’s not a combination that lends itself to a lot of hope. So I dream of moonshots.

The Pew Data is stark: nobody believes the government can be trusted anymore.

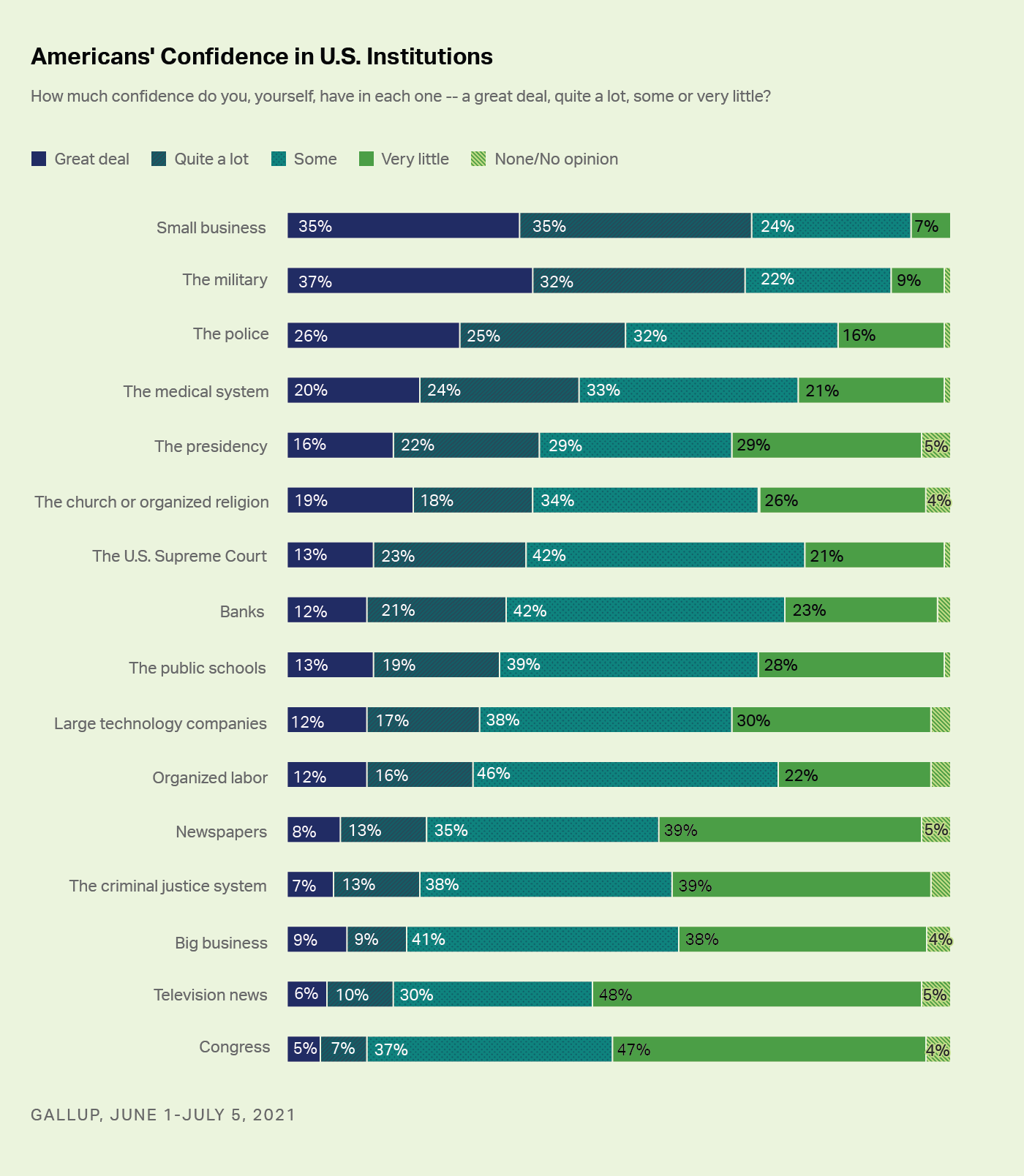

But then, Gallup tells us we have faith in very few institutions at all.

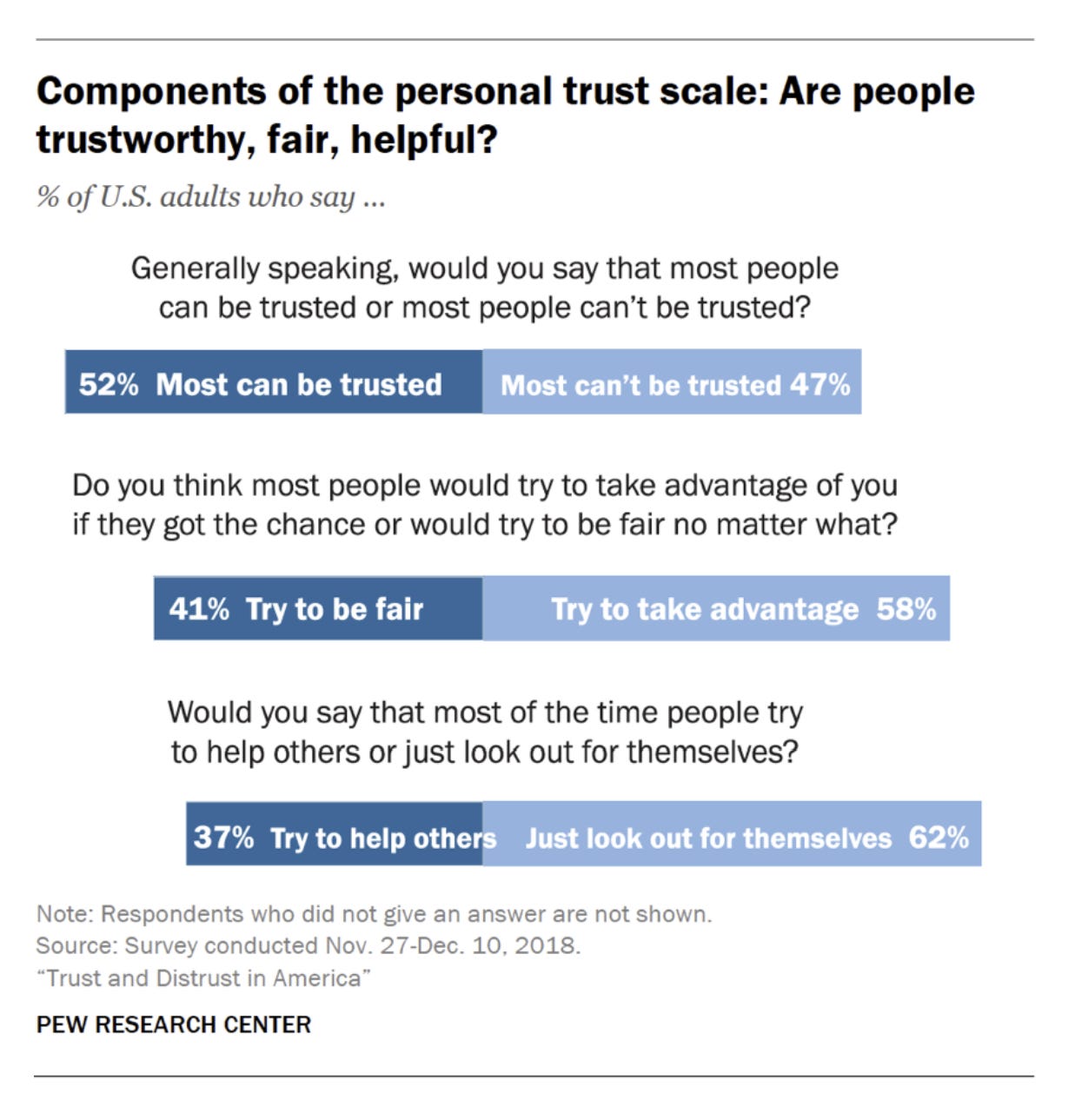

We don’t trust each other either (Pew).

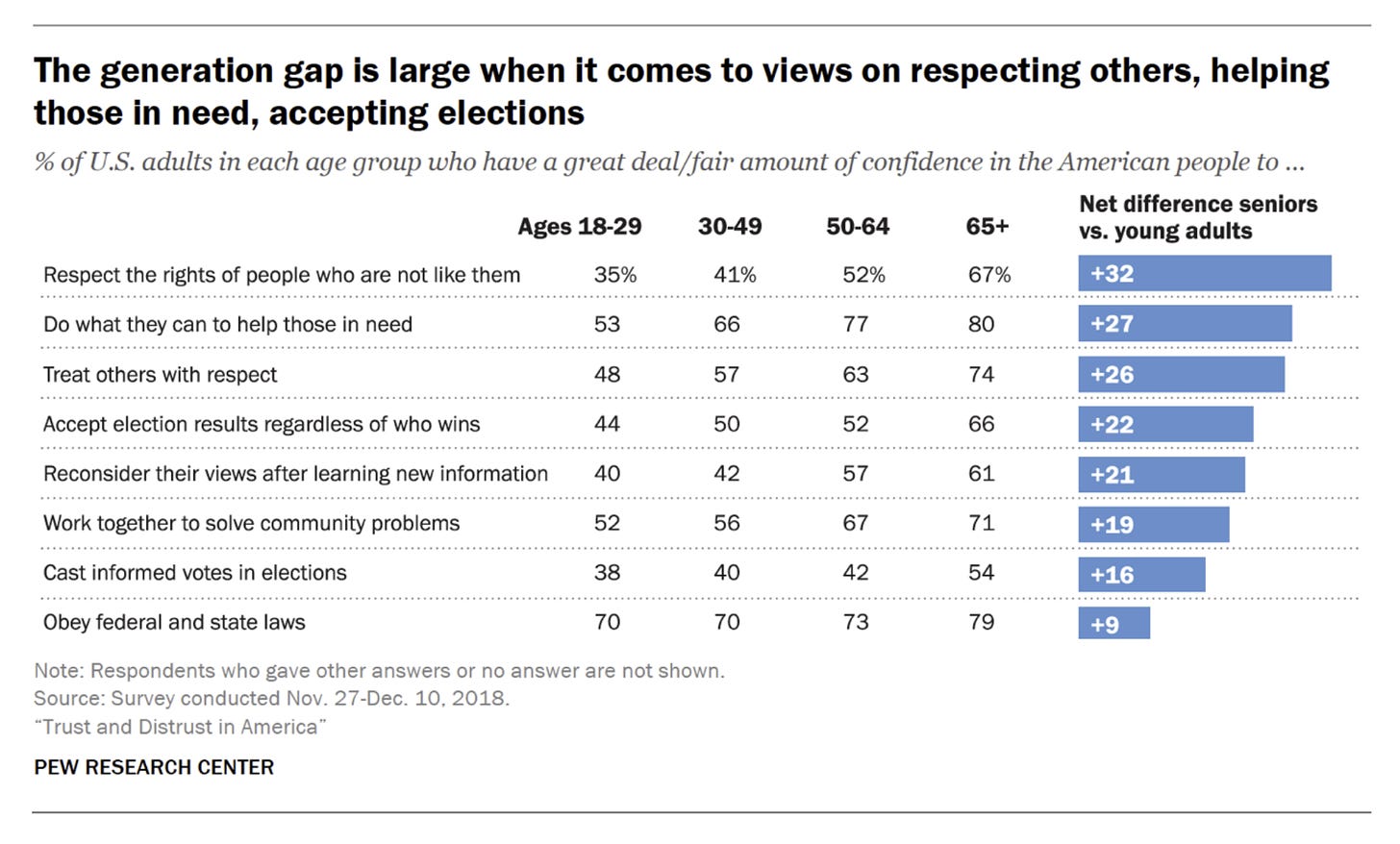

And the younger you are, the less trust you have, not a great trend.

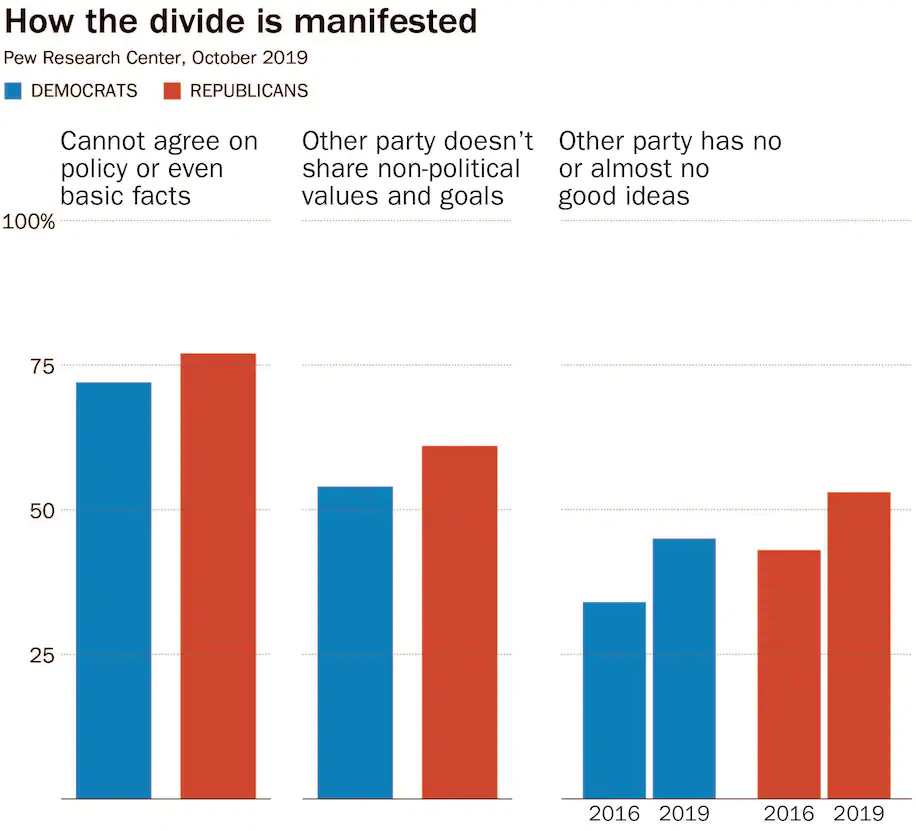

Of course we hate “the other side” and that hate is growing in intensity.

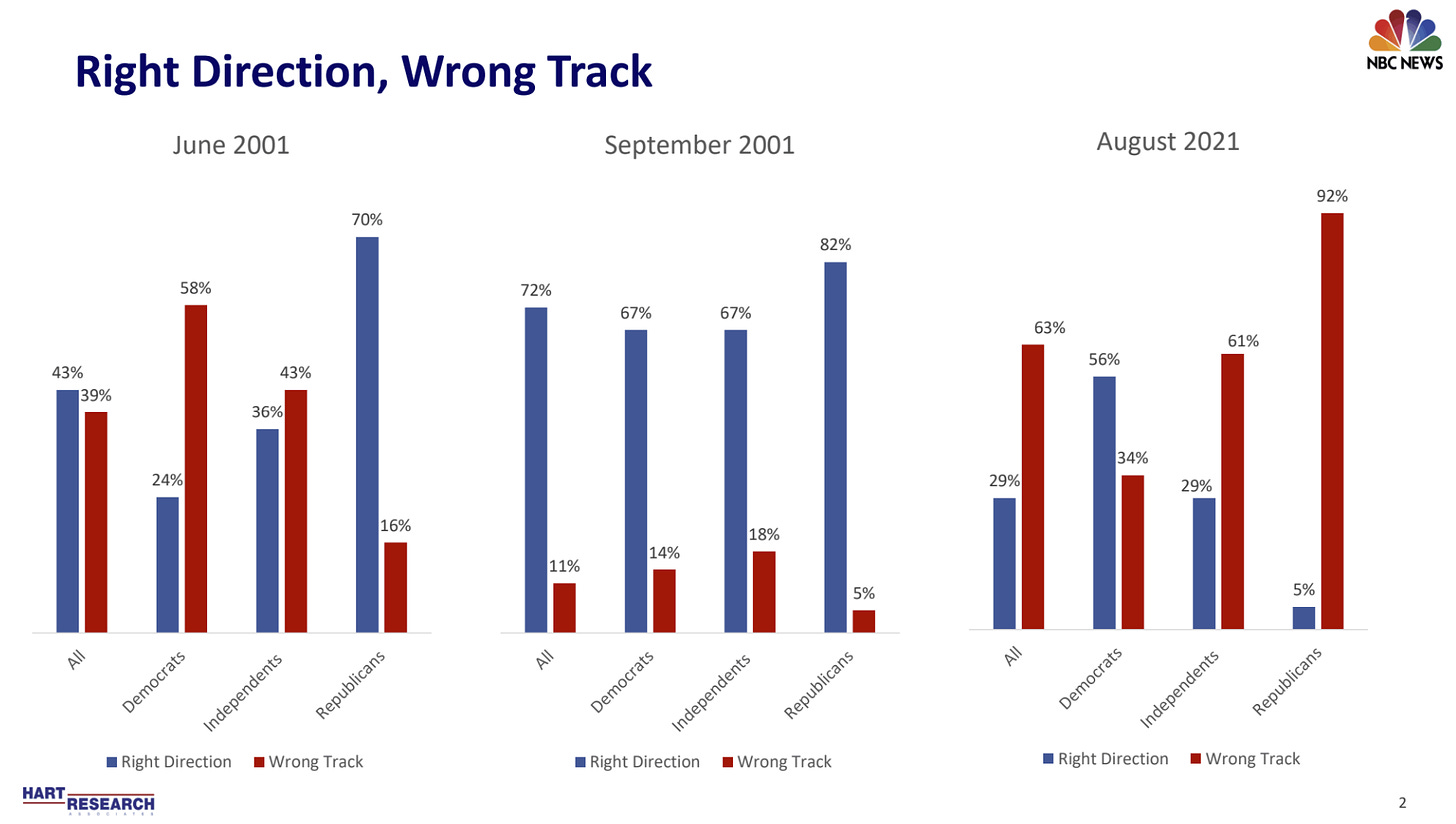

And we are really a remarkably pessimistic country these days.

OK. But what are the actual effects of a lack of social trust, partisanship, and immense pessimism? Among other things, I think we simply can’t trust that a solution to a social problem that requires behavioral changes among Americans is actually a solution. Because when the citizenry doesn’t trust the government, the major institutions of civic life, or each other, hate the half of the country on the other side of the partisan divide, and think life is getting worse despite economic and technological growth, what force is going to compel them to sacrifice for the greater good?

The obvious place to start here is Covid precautions. They’re an interesting litmus test because, though they certainly have a component of shared responsibility, they’re also clearly a matter of selfish interest. Though I recognize that Covid panic often springs from socially competitive interests and am frustrated by Covid safetyism, I also firmly believe that vaccines, boosters, and masking are essential precautions in a pandemic. But even when it comes to survival, to literal life and death, culture war and polarization are strong enough to keep people from changing their ways, and I have to imagine that the vast majority of the unvaccinated will never change that status. I also have no faith that vaccine mandates would work, even setting aside civil liberties concerns - there are too many legal, procedural, and pragmatic hurdles. I still post charts and graphs to stress the importance of vaccination on my Facebook, but it’s all vestigial at this point. Because we can’t get people to change their behavior. Not in America, not in 2022.

The vaccine issue demonstrates that even successful technocratic solutions can be caught in behavioral choke points. I suppose it’s too early to tell if the initial optimism about Pfizer’s Paxlovid was justified, but I’m pinning a lot of hope on that and other therapeutics because for some bizarre reason some of the unvaccinated will take those drugs despite their fear of vaccines and Big Pharma - half of them, at least. Either way, the only faith I have in combatting Covid-19 lies in medical science. We develop the drugs and vaccines (or, I don’t know, virus-hunting nanites) that solve the problem or we don’t. And in the meantime we should invest massively in overhauling existing ventilation systems, for the next airborne pathogen if not for this one. I have far more faith in our ability to build physical infrastructure, even as unconscionably expensive as that has become, than I do to prompt behavioral change.

In the 2000s and 2010s there was a great deal of ink spilled on “nudges,” Cass Sunstein-style tools to change behavior. (He’s still doing his thing.) I think we should now consider the possibility that we can’t nudge many people to do much of anything, in current conditions. Yes, you can put a cartoon bee on a urinal so that dudes are less likely to spray piss all over the room. But you can give people the choice “would you like to take this free shot, or else potentially die of a preventable respiratory infection?,” and a healthy number of them are going to say, “fuck you, don’t tell me what to do!” Yes, there are all manner of things we could do at the margins for a more sensible Covid response. But at the end of the line for most of them is a human being with the power to resist, and many do resist even in the face of severe illness.

So, to return to the discussion of expanding Manhattan, what’s your alternative? Convince thousands of New York millionaires and billionaires to make concessions in order to reduce the cost of housing? Against their financial best interest? Please. Of course we have to try, but I think getting really widespread land-use regulatory reform is no less of a Hail Mary than geoengineering. YIMBYs have had some victories lately, which is good, because YIMBYs are mostly right. (Albeit while maintaining a truly obnoxious online social culture.) But part of the reason there’s been some success in sensible zoning and housing regulation is that the forces arrayed against such change haven’t really noticed yet. When they get better organized, opposition will be fierce, as a lot of people with deep pockets don’t want change. I 100% believe that it would be easier to literally turn the ocean to land than to convince people that their park views and parking mandates have to go in order to increase density.

Look at another issue Barr raises, mitigating the effects of climate change. Let’s broaden out from the question of New York’s specific storm surge issues: I don’t believe in any responses to climate change that aren’t fundamentally engineered solutions, because first-world people aren’t going to change their energy use behaviors and the third world can’t afford to. Ideally this would come from swiftly changing to renewables and a reinvestment in nuclear power. Pragmatically it may have to involve some sort of major carbon capture program, technology that somehow sucks carbon directly out of the atmosphere. It’s hard to get people to agree to consume less energy, whether at home or in their cars, and I have never observed a particularly strong correlation between political concern for climate change and taking personal action to reduce one’s carbon footprint. And the kneejerk recitation of the argument that only reining in corporations can slow climate change, however true it may be, does not change the fact that we’re almost certainly not going to do that, either. So carbon capture seems essential.

Yet as someone who’s pretty plugged in to environmental circles, there’s a ton of skepticism and antagonism towards carbon capture and similar engineering approaches. There’s legitimate arguments about their potential efficacy, I’m sure; this brief paper from the Center for International Environmental Law lays out some compelling points. The problem is that a lot of the resistance to carbon capture within the left seems powered more by resentment than technical criticisms. For many, it seems, carbon capture is “cheating” - we got into this problem through excess and bad behavior, and we should have to get out of it with discipline and selflessness. For the record, I find this strain of climate moralism deeply unhelpful for confronting the actual problem, and arguments about it too often become vague complaints about corporations. (Yes, corporations are bad actors who contribute a great deal to the problem, but we need to be specific and pragmatic to solve climate change.) Besides, it does not strike me as remotely plausible that enough Americans would be moved by the appeals to the greater good to solve a problem where blame is diffuse, the effects are slow-building, and the required behavior involves self-sacrifice.

I have to underline this point: this is not at all a comfortable or natural position for me to be in. I’m opposed to solutionism, for one thing, the assumption that every problem in the world has a specific and discrete fix through policy. More to the point, I tend to be alienated from the people and cultures that insist on engineered solutions to social problems, as they are often associated with libertarian political principles and are deeply intwined with capitalist excess. What’s more, the issue on which I have the most expertise and have written about most extensively, education, has proven uniquely ill-suited to engineering solutions. Again and again, policymakers and deep-pocketed do-gooders have attempted to use money and technology to solve our educational problems, only to rediscover once again that the problems can’t be solved that way. (The $1.3 billion paid by the Los Angeles public school system for iPads - at higher than retail price! - will always live in infamy.) There are many problems in the world, I’m afraid, that can’t be solved just by putting together the right blueprints, and the “just send in the coders to solve the problem” attitude can often be quite destructive. Building bridges is easy compared to many human problems.

But here I am nonetheless. I haven’t given up on solidarity or turned entirely nihilistic about the American people. But the worse among us are so quick to say “fuck you, I got mine,” while the better are so quick to say “lol nothing matters we’re doomed lol lol,” that I’m just about out of faith in social solutions.

Let me leave by complaining once again about the state of our discourse. Whether as pure thought experiment or realistic proposal, I thought Barr’s piece was generative and fun. I would love to live in an intellectual culture in which such provocations are riffed on by those who are interested (whether in praise or blame) and ignored by those who aren’t, where people could either call the idea good or bad responsibly and seriously, with the support of evidence. Instead the communal response from writers and academics, the people who are supposed to take ideas seriously, was mostly like this:

In the fusion debate I get the sense that some people really don’t want it to work. Why? Because if it works people will be happily driving their electric Tahoes to their 5,000 sq/ft McMansions an that’s just wrong.

Why is it wrong? Because of climate change. But there would be no climate impact. Well…I find that lifestyle ascetically revolting. Is the closest to an actual reason I can think of.

I'm just going through put it bluntly. Many on the left thought Climate Change would finally be their big win politically and they care almost as much about this as they do about climate change itself. I've lost count of how many times I've heard some kind of quasi vulgar materialist argument that "climate change will make things so bad people will have to turn on capitalism" or something similar. It's hopelessly naive to expect to profit politically off such a crisis. The left sure as hell doesn't seem to have benefitted much from COVID and that made a lot of people's lives worse too. The retort is often "well, COVID just didn't make people miserable enough. It'll have to get even worse to really change things." So we're firmly in "the worse, the better" territory.