I was on the Wisdom of Crowds podcast with Shadi Hamid and Damir Marusic recently. Check it out.

I attend therapy every week. I have for a long time, now, after drifting in and out for years; finding and affording a therapist in New York City was just very hard. One nice thing about moving out of the city has been that, though our national medical system remains an embarrassment, it’s much easier in suburban Connecticut to find doctors and get appointments, to say nothing of those appointments starting on time. (In eight years living in Brooklyn I never once had a doctor’s appointment that started less than 45 minutes after the scheduled time. Literally never once.) I go and I sit and we talk and we go through the therapeutic process. Mostly it’s chill and uneventful. Sometimes it isn’t. Personally, I find the process beneficial. I pay a professional to address specific needs I have, and they are slowly and imperfectly addressed.

Therapy is a medical tool that, like many medical tools, rose from dubious origins; in fits and starts, it’s been gradually made more scientific over time. Therapy has a lot of potential benefits for the right patients. Some types of therapy have much better research records than others, and knowing which to pursue can be tough, but in just about all of the literature most patients get something valuable out of the process. Of course, therapy can be more or less useful, a therapist can do a better or worse job, and in particular the interplay between a patient and therapist can result in different outcomes of various levels of medical utility. My perception, unfortunately, is that a lot of therapists essential treat therapy as 50-minute long exercises in enabling their patients, telling them what they want to hear, and doctor-shopping makes that condition hard to avoid. (If you never get upset about what your therapist tells you, then they’re probably failing you as a therapist.) But I suppose that’s none of my business. Therapy is a good tool for me because I have some problems of the type that therapy is well-suited to address; not everyone does. I find the notion that everyone should be in therapy very strange, just like I would it strange if it was routinely said that everyone should be on antibiotics. But the existence of therapy, writ large, is on balance a very good thing. I am close to many people who have used therapy to ease pain and become healthier people, and for that I’m grateful.

I say all of that mostly because of the title I’ve chosen here, as I don’t want you to think that I’m opposed to therapy as such. In fact I’m here to complain, as I have before, about the way therapy has gone from being a tool to being a culture, in a way that’s bad for everyone. Let’s consider this piece in The New York Times, about forgiveness and why it’s bad, merely as an object lesson.

I’m only somewhat exaggerating or joking when I suggest that the piece argues that forgiveness is bad. It would be more accurate to say that it expresses an attitude generally skeptical of forgiveness as a concept, running to out-and-out antagonistic, speaking as though a virtue that people have embraced for thousands of years is some sort of con or dodge or scam. The charming headline reads “Sometimes, Forgiveness Is Overrated.” It’s part of the NYT’s Well vertical, which is to say, the self-helpy part of the paper that plays to the anxious and aspirational, a very important reader demographic. Writer Christina Caron reaches out to “the experts” to ask about the value of forgiveness and arrives at a conclusion that’s something like… eh. You see, the fundamental argument in the piece is that, because forgiveness only sometimes soothes the feelings of the forgiver, forgiveness is therefore overrated. Caron and those experts - what it could mean to be an expert in forgiveness, I have no idea - insist that the cultural directive to be forgiving is misguided, because it’s not always strictly speaking what’s best for the person who might forgive. That is the argument of Caron’s piece: that you should contemplate forgiveness only when and because it might benefit you. If it doesn’t, you should feel no pressure to forgive, let alone believe that you have an affirmative obligation to forgive.

Caron writes, “therapists, writers and scholars [are] questioning the conventional wisdom that it’s always better to forgive. In the process, they are redefining forgiveness, while also erasing the pressure to do it.” That is a constant, recurring theme of the whole therapy-as-culture genre, the notion that social pressure, the pressure to do something the individual doesn’t want to do, is inherently bad, inherently wicked. The notion that much of the difficult work of life is about working against our base individual desires, and the idea that we need to build social pressures to support this work, are both casually discarded as pathological. Better to feel no pressure to do anything, in pursuit of a self-actualized life. The directive to forgive is as old as human morality, but the wisdom of the past is of little concern compared to the impulse of the moment. Caron dismisses the opinion of Desmond Tutu, who resisted apartheid and risked his life in doing so and still emerged as a champion of forgiveness as the highest calling of human affairs. But what would such a man know, compared to the busy little strivers out there looking for even more permission to live only for themselves?

Much has been written about why forgiveness is good for us. In many religions, it is considered a virtue. Some studies suggest that forgiveness has mental health benefits, helping to improve depression and anxiety. Other studies have found that forgiveness can lower stress, improve physical health and support sound sleep.

This is all setting up a very big “but,” and it also establishes the terms under which Caron might consider forgiveness good or bad - with an actuarial table. This attitude is the nut of the whole thing, an attempt to justify or undermine transcendent human virtues with links to PubMed. That we might want to embrace moral virtues like forgiveness in the pursuit of benefits that can’t be measured with an Apple Watch goes unconsidered. The idea that there are higher virtues towards which we might labor is nowhere to be found. This passage’s implicit value system would justify saying that compassion is good because it reduces blood pressure, that honesty is good because speaking the truth causes a pleasant release of endorphins, that you shouldn’t rob and murder someone because doing so might worsen fine lines and wrinkles. It’s a stance on morality that has completely excised the interests of others, which is to say, an anti-morality, a consumer product marketed in moral terms, a justification for selfishness bought off the rack.

Do you want to know what ideology is? What we mean when we say “ideology at its purest”? It’s not a collection of policy positions. It’s not a political party you vote for. It’s not even your conscious beliefs about right or wrong, your philosophy about how humans should act individually and collectively and the relationship between those acts and the public and private good. No, ideology refers to those beliefs you do not examine because you do not see them as beliefs at all. Ideology isn’t a matter of ingesting arguments about better or worse, right and wrong, and evaluating them to determine your own beliefs. Ideology is fundamentally the unexamined framework of the system through which you perform such an evaluation, the part you can’t and don’t see; it’s the assumptions that you cannot understand as assumptions. And the ideology that Carons demonstrates here, the set of assumptions she can’t begin to examine critically because she does not notice them, says that the individual has no responsibility to anyone but themselves. There is no moral duty, there is only the immediate emotional needs of the individual, which eclipses all other concerns, which is sacrosanct. Read the piece! Find me any suggestion whatsoever that other people exist and that we all have moral responsibilities to them, and that putting those responsibilities first is at the heart of emotional integrity and maturity. Those ideas simply aren’t considered.

You could certainly say “I don’t think putting responsibility to others first is at the heart of emotional integrity and maturity.” That’s certainly fair game. But if you believe that, you’d have to consciously understand yourself to be holding that position and then argue it. Doing so might very well compel you to undertake a process of self-examination that reveals things you don’t want to know about yourself. This is ideology, the beliefs under the beliefs that enable us to go around as little believing creatures, without confronting things about ourselves that we don’t like. We all live in ideology, and we’re all hypocrites. Definitely including me. That does not mean that we can’t point out the negative consequences of someone else’s.

Of course you don’t have to forgive every individual person in every individual scenario. That’s senseless. But then, no one ever said that you did. We have a vestigial communal sense that forgiveness is good and important, for the very sensible reason that we are all fallible and thus are all deserving of some kinds of forgiveness, sometimes. Believing this does not, as the essay implies, mean that we have to forgive our rapist, specifically. It does mean that we should take great care to consider the value of forgiveness as a quality aggregated across society, which can only run smoothly if a) people become infallible or b) we create social and emotional structures that can account for fallibility. I know which one seems more likely to me! Either way, while forgiveness certainly can and should result in blessings for the person doing the forgiving, to cast forgiveness as purely a boon for the individual is a category error. We are compelled to do things all the time that may be contrary to our own immediate desires, for the benefit of others. You may call this socialization or enculturation or maturation or whatever you prefer. But this communal drive is, in its essence, the same drive that inspires parents teach their kids that they can’t just pull their pants down and poop on the floor whenever they feel like it. If anyone aggressively commands you to forgive someone who abused you, please feel more than free to tell them to fuck off. But throwing the baby of an essential social good out with the bathwater of emotional inconvenience is harmful.

What disturbs me so much is the notion that the only criteria for deciding whether a behavior is worth doing is the individual’s own emotional comfort. That, and my sense that Caron has no idea she’s endorsing it.

“If you’re asking the question about whether or not you forgive, move away from the question and ask, ‘What do I need to work on to free myself?’” said Dr. Bakari, who holds a doctorate in educational psychology.

Who told you that your job in life is to free yourself? “Freeing yourself” is very often the opposite of pursuing moral action. Very often, the reason that there’s someone who you might or might not forgive, the reason for the offense, is precisely because that person had freed themselves in an entirely inappropriate manner. (A lot of the world’s most predatory people are those who feel much too free.) Who told you that your emotional comfort is the heart of the moral challenge? The moral challenge resides in the face of the other. And who needs this? Is there really an insufficient supply of influences telling you to put yourself first, in 21st-century America? What are we doing, telling a civilization full of people raised on capitalist selfishness that they need to be more selfish?

I have spent a good deal of time pointing to bizarre and unhealthy Instagram self-help meme culture. I admit that this is often a matter of picking low-hanging fruit, which is fun and easy because a lot of this stuff really is deranged and people find it entertaining when I make fun of it. But I actually do think it’s important on a more meaningful level. I am convinced that the never-ending adult enculturation process we’re all undergoing all the time is far more directed by the minor influences of ordinary life - ambient cultural attitudes, day-to-day exposure to coworkers and friends and social media and television - than it is by abstract political, religious, and moral concepts. And the culture that we’re creating genuinely frightens me. Between said capitalist selfishness, helicopter parenting, social media platforms that inherently reward narcissism, and this whole bonkers quasi-feminist woowoo school of aspirational self help, there’s a never-ending supply of messages telling impressionable people that they should put themselves before others, inverting the most basic human moral principle.

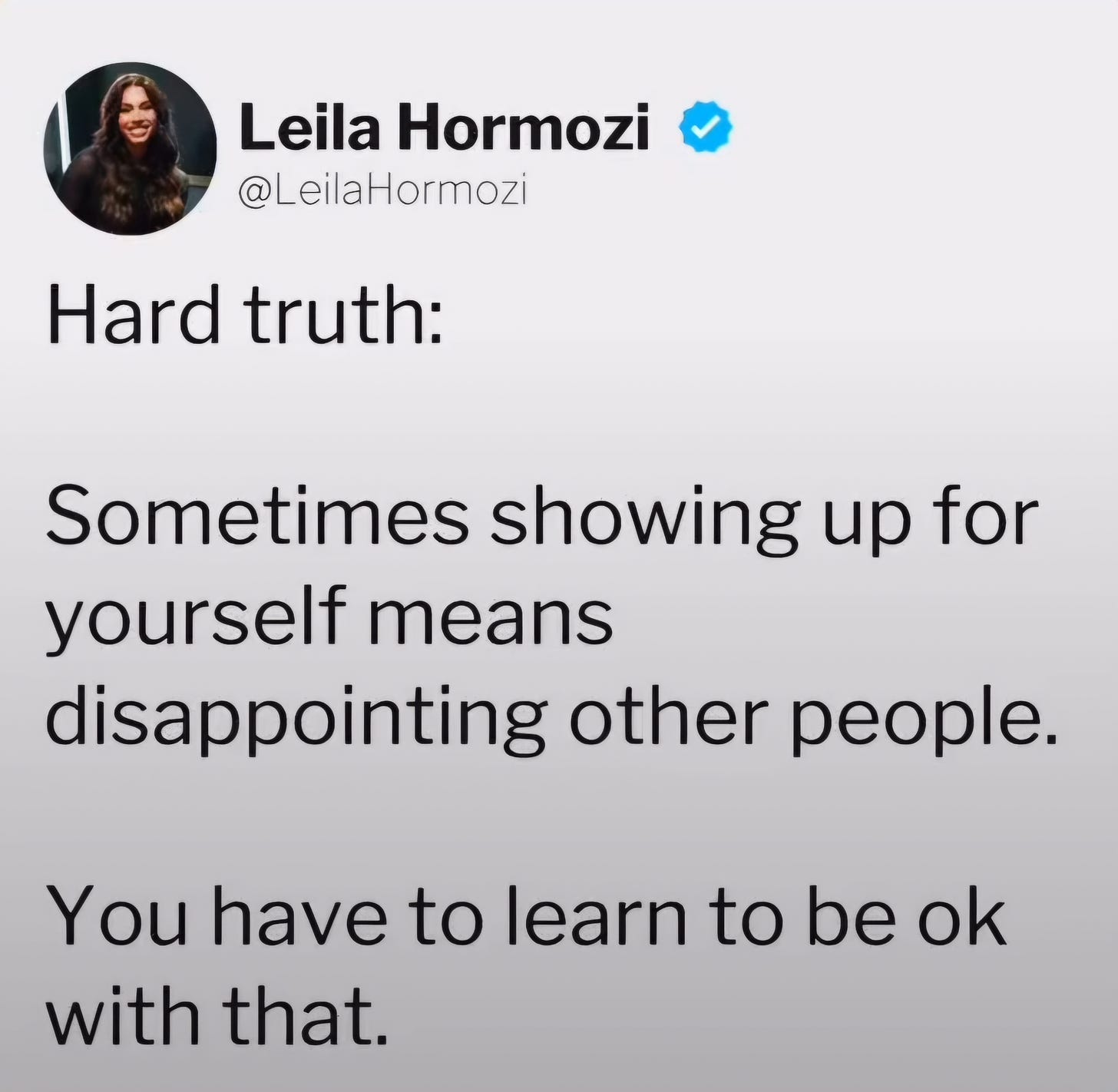

So let’s not pick particularly low-hanging fruit today. Let’s take a more measured and innocuous version than the kind I usually highlight in this space, a Twitter screengrab that was widely shared on Instagram.

This is not, obviously, of the same tenor as the memes I often point to in this space, which are often of the type “You are an ancient and celestial being, and you have a divine right to manifest everything you have ever wanted, no matter who gets in the way.” (That is not an exaggeration of the type of rhetoric found in that discursive space, and if you think it is, I challenge you to go investigate on Instagram yourself.) This is far more measured: if you want to “show up for yourself,” a bizarre concept but one that fits with the boutique vocabulary this world has invented, you need to disappoint other people. You have to learn to be OK with it, to become emotionally comfortable with disappointing others to “show up for yourself.” Well, surely there are times when we are compelled to put our own needs before the needs of others. The trouble is that becoming OK with it can very quickly degrade into not even noticing how you’re disappointing others while you pursue your ruthless self-interest. And since this whole strange discourse produces pretty much exclusively this message and not its opposite, the notion that you need to be willing to put others before yourself, the justification for just being a selfish asshole will always be there. This is why I refer to this stuff as sociopath instructions; it’s a readymade set of excuses for why you are the most important being in the universe, in handy meme format.

The question remains, who in the world could possibly look out at contemporary society and think that the message “put yourself before other people” isn’t loud enough? Every women’s site on the internet preaches this message. Every hustle bro on Threads preaches this message. Every therapist between San Diego and Sacramento preaches this message. Every eight-word meme in overly elaborate cursive font on Pinterest preaches this message. Every asshole who’s still holding on like death to GameStop stock preaches this message. There’s the girlboss version and the Joe Rogan bro version and horoscope obsessive version and the Wall Street grindset version and the fitness guru on trenbolone version…. Justification for selfishness is not in short supply. It is the water in which we swim. I don’t know why we need to get more in the pages of The New York Times, dressed up in social science research, giving us the therapy version, the Trauma Industrial Complex version. Who is this for?

I genuinely worry, in this world where the Christina Carons have so thoroughly captured the PMC messaging apparatus - where the very idea that there are duties that transcend the duty to the self has become unthinkable - that we’re training a species of bad people. There are things that you are bound by integrity and conscience to do that you will not like doing, and only you can decide whether to do them. Society has a vested interest in pushing you in one direction, but that has now been labeled pathology. For many many years, a certain strain of conservatives has fretted over the right’s combination of capitalism and Christian morality, wondering what becomes of the latter at the hands of the former. I think many of them would admit, after a few beers, that the morality is no match whatsoever for the market. This is a specific sickness within contemporary American conservatism, which is a very strange animal, but it’s also something like the broader dilemma facing those of us who live within material abundance and spiritual emptiness in late capitalism: without God and apple pie, how do you create structures that compel people to be less selfish?

What’s happening in much of our culture amounts to answering that question by refusing its challenge - by saying that we don’t need less selfishness, thanks, but rather more. And the particular misery is that they’ve found a ruthlessly efficient and impregnable means to defend that position, therapy. Not therapy in terms of going to see a licensed clinical practitioner of some sort and undertaking a (hopefully evidence-based) process to achieve specific medical goals related to mental health and wellbeing. But therapy as in therapeutic culture, the offloading of all of the human project into the domain of psychiatric care. The basic work of life, human interrelations that involve multiple people who all have their own legitimate points of view, is reduced to being an exercise in one person’s pursuit of self-actualization. We all become bit players in each other’s plays. The abstruse vocabulary lends self-interest the sheen of medical legitimacy, and it also carries with it a potent discursive cudgel: anyone who disagrees with or criticizes someone who invokes the therapeutic mode is an impediment to them healing from their trauma, perhaps even guilty of retraumatizing them. In the NYT piece, Caron repetitively mentions women who have endured very real trauma, which has the inevitable effect of making her piece seem like the voice of the traumatized. But of course what people want and what they need are not the same, and anyway, because everything that lives experiences trauma, exempting the traumatized from social rules simply removes social rules entirely.

In the place of rules devised by moral philosophy and religion, therapy culture has erected others, such as

You, your feelings, and your goals are always preeminent and in any conflict supersede those of others

You are entitled to total and complete emotional safety at all times, and this entitlement supersedes the rights and desires of others

Simultaneously, you are a totally, existentially, permanently fragile being

Since there is nothing that can be endured or recovered from that is not injustice, the concept of resilience is itself an expression of injustice

That which makes you feel better is that which is right to do

In any conflict between any two people, there is always one guilty abuser and one blameless victim

You argue, they gaslight, you have self-respect, they are narcissists, you are still growing, they are toxic, you have boundaries, they have limitations, you hold space, they stand in the way of your growth

Your own behavior is always a trauma response, and thus not your fault; the behavior of others is always freely chosen, and thus responsibility-bearing

Any of your behaviors is merely one small step on your journey, and you are still in the process of becoming yourself, any behavior of others you don’t like is constitutive of their very being and cannot change

Wanting and not getting, for you, can never be an expression of the basic reality of existence, but rather is always evidence of crime, abuse, mistreatment, pathology, injustice

Everything you feel, do, and are is valid, always valid, until the end of time

You’ll note that this is not just bad for those who must live alongside someone ensconced in therapeutic culture, but presents utterly unattainable goals to that person, ensuring that they will never graduate out of therapy-as-way-of-life. The point is to heal and grow so that you don’t need therapy anymore, after all. That idea has essentially no presence in therapy culture.

And the real twist of the knife, from where I’m standing, is that a lot of people really could benefit a great deal from therapy. It’s not a tool that can address every problem; in fact, most human problems are not addressable via therapy. The way that the tool of therapy has become this all-purpose symbol of aspiring to live healthier and more authentic lives is very unfortunate. But that doesn’t undermine the fact that there are a lot of people who could use a regular and structured experience in self-exploration, addressing persistent emotional and personal problems, guided by a trained professional. (Unfortunately, the people who need it most are often the least likely to get it, while the most likely to get it are often the ones most likely to misuse its processes and insights.) I don’t want to be a therapy basher; I want to rescue therapy from therapeutic culture. And I also want people to think about how deeply dangerous it is, to create this excuse architecture for people to care only about themselves, to believe that what’s best for them and what’s medically necessary and what’s socially just are all and always the same. I don’t think Christina Caron or the quoted experts are bad people, but I do feel a little crazy over their gullibility. Can you not understand how many people are going to misuse this philosophy? How easily genuinely bad people could exploit it?

Therapy for specific tasks, undertaken with evidence-based approaches by trained and licensed professionals, with an understanding that someday therapy should end, available for all. That’s the goal. And then, outside of your therapist’s office, please shut the fuck up about what therapy says you have the right to. Therapy is about you and your thoughts and feelings, not about compelling other people to do what you want them to because you justify it in therapeutic terms. Out here, beyond your therapist’s office door, there’s the rest of us, and we have rights and needs too.

It isn't simply that therapy culture taken to its extreme problematizes the concept of doing anything that might vaguely be construed as uncomfortable or done for the benefit of someone else; there's also the inevitable observation that the people most likely to shout self-care and putting your needs first are also the ones most likely to call, politically, socially, or otherwise, for the need for *other people* to change in order to make society less toxic, less bigoted, less bad.

It's one thing to be so deep into the pool of self-affirmation that accepting the possibility of self-work might feel like oppression, but I think Freddie realizes that this dynamic can't credibly co-exist with the kind of politics that claims that we all need to make sacrifices and Do The Work to overturn all the prejudices, structural failings, and -isms in the world. (Moreover, as Freddie has pointed out in the past, politics- organizing, outreach, trying to win hearts and minds- *is* hard work, and the act of trying to convince a skeptical voter why they should switch to your team inherently butts up against the therapy mandate to never breach the boundaries of one's own comfort zone.)

Everyone is entitled to their own petty hypocrisies, and of course you can't force anyone to forgive anyone else, but this particular hypocrisy is one that renders a significant part of the entire leftist project ripe for dismissal. And I get the sense Freddie recognizes this more than all the self-affirming Christina Carons of the world.

As much as everyone rolls their eyes at the constant use of "expert" in The NY Times, this has to be the best yet. The problem with Jesus Christ was that he didn't do p-hacked, easily falsified, publish-or-perish studies to determine whether we should forgive our brother 490 times