This is the third post in (the first annual?) Mental Illness Week at freddiedeboer.substack.com.

Nobody feels good about the state of American mental health care. Happily there’s a lot of agreement about what’s wrong and even what could fix things, though the anti-psychiatry movement - which, once again, please leave me the fuck alone - would certainly disagree. And yet the problems seem intractable, thanks to the general structural problems of health care funding in the United States and the specific issues with psychiatric medicine, including resistance to care and treatments that are only modestly effective, carry debilitating side effects, or both.

Dr. Thomas Insel is in a good position to take a bird’s eye view on the entire system, as he served as the director of the National Institute of Mental Health from 2002 to 2015. (He presumably did not take part in any experiments to increase the intelligence of rats.) Insel is not just a psychiatrist but a neuroscientist, and he was part of a revolution in seeing psychiatric medicine as essentially a branch of neuroscience, a movement to seek the physiological origins of mental illness and treat with that knowledge. Given the degree to which psychiatry was and often still is associated with seeking origins for mental health problems in vague childhood traumas and assigning treatment with embarrassingly little scientific evidence, this was all very sensible, and for the record I think there’s no real long-term progress in this field that does not entail better understanding of the brain. But at the very beginning of the book, with admirable bluntness Insel admits that the revolution he was a part of was a failed one. Massive investments of money, time, and energy into brain research have not led to more effective treatments of mental illness, and in fact have borne little fruit even in terms of basic understanding of the brain.

So Insel’s new book Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health is in some ways a mea culpa. And it’s a (consistently interesting, somewhat cliched, overlong) embrace of a different paradigm, that of true community medicine, of a whole-patient philosophy, of the “three Ps”: people, place, and purpose. It’s an argument, if you’ll forgive me, that it takes a village. That argument is not wrong, and on specific issue after specific issue I would love to be able to make Insel’s vision come true. But for me, Healing is just not particularly compelling as a description of reforms that can actually happen in any likely near future.

First, I want to highlight a point he makes early on: the deinstitutionalization movement, still lionized by many left-leaning people and frequently represented as a triumph of humane public health policy, was a disaster.

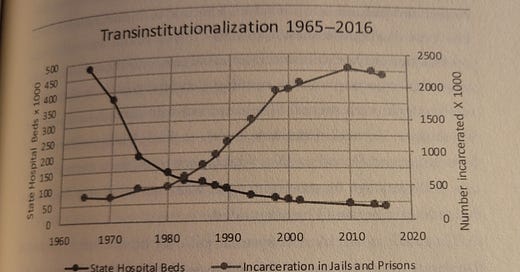

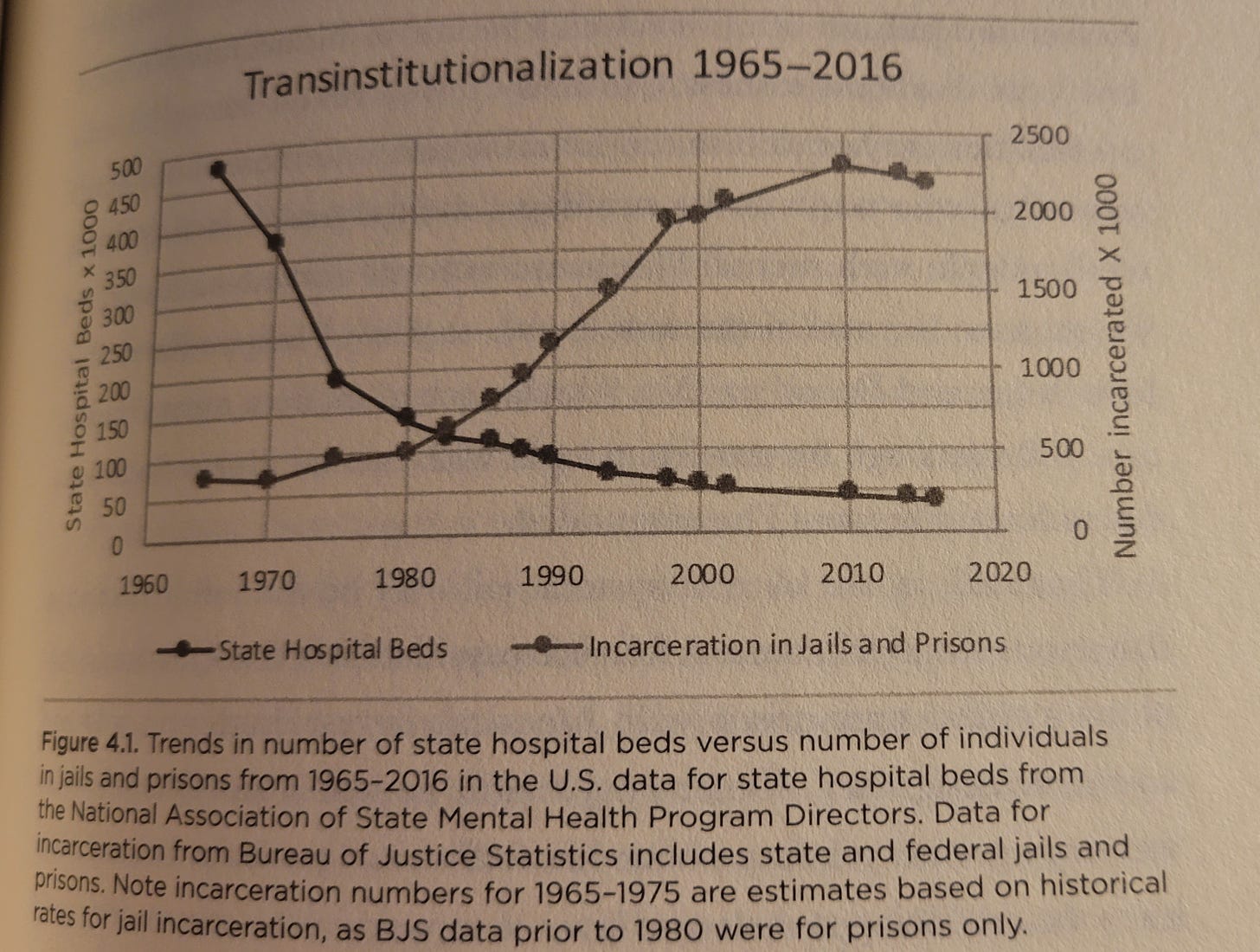

If you’re unaware, deinstitutionalization was a movement of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s to shutter state mental institutions (asylums), under the theory that such facilities functioned as warehouses for some of society’s most vulnerable. With the specter of lobotomies and patients in straightjackets locked in padded rooms hanging over psychiatric medicine, John F. Kennedy pushed for deinstitutionalization with his 1963 Community Mental Health Act, the last major act of legislation he ever signed. Many of the existing mental health facilities were in fact not healthy or nurturing spaces for their patients. The trouble is that, aside from a few federally-funded institutions that had widely differing levels of care thanks to inadequate standardization, there was nowhere for patients who left the state facilities to go. Nowhere, that is, except for prison, which is exactly where they went, as the graph above shows. I still interact with many people who defend deinstitutionalization; they are generally the same people who think injectable antipsychotics are abuse and that no one should ever be involuntarily held in a psychiatric facility, despite both saving countless lives.

(A great history of the failure of the Community Mental Health Act’s ambitious, misguided quest can be found here.)

Even absent the deinstitutionalization fiasco, American mental health care would no doubt be a tattered patchwork quilt. What are some of the big-picture problems with our system?

The same immense access and affordability problems as the rest of American healthcare. We lack a national system that ensures universal access to medicine, and our care is among the most expensive in the world.

Even within the context of the American system, psychiatry is rich people’s medicine. Insel quotes incredible numbers, such as the fact that 57% of American psychiatrists do not accept Medicaid while 45% do not accept conventional health insurance. A vast number of doctors and institutions in this country accept only cash payments, in practice if not by admission, effectively shutting out not just the poor but the vast majority of the working and middle classes.

Though there are a huge number of people working in the broad field of psychiatric or psychological medicine - there are more psychiatrists than any other physician specialty, save internists or pediatricians - they are profoundly unevenly distributed by geography, leaving many parts of the country starved for care, especially from specialists. Likewise, some professions and roles within the profession appear to be overrepresented, while others are woefully short-staffed, especially nurses.

As suggested above, we lack basic scientific knowledge about core elements of the brain, how it functions, and its relationship to the mind, a degree of ignorance about elementary functioning that is rare in other avenues of conventional medicine.

The field is far less scientifically based and evidence-driven than other fields of medicine, and some forms of effective medicines are simply underutilized, often because personnel haven’t been trained in them. In therapy in particular there is an attachment to outdated and empirically unjustifiable psychoanalytic techniques, typically fixated on childhood memories, while far more scientifically sound approaches (such as behavioral activation for depression) are barely attempted.

Too many of those who need mental health care the most only receive it in light of an immediate psychiatric emergency, such as a psychotic break; as Insel says, this is like “managing heart disease one heart attack at a time.”

To a degree that is unusual relative to other diseases and disorders, those who suffer from serious mental health issues are frequently treatment-resistant, typically thanks to the nature of those illnesses themselves, that is, how they commandeer the mind.

Though none of this was novel for me, Insel draws it all well, and the book is if nothing else a good overview of the current state of American mental health care for those who want one. I would perhaps like a little more insider knowledge on behalf of the former director of NIMH (there are no juicy institutional tidbits here), but it’s yeoman’s work. Insel illustrates his discussion with stories of patients, composites of typical people with typical mental health problems like schizophrenia, anorexia, or depression. These too are mostly well done, if sometimes a little on the nose.

When it comes to his description of where we are, the only place I have to complain is Insel’s somewhat rosy description of the efficacy of currently-available treatments. There’s in fact an entire early chapter that takes as its major message that, contrary to what’s sometimes believed, our mental health care problem is an access problem and not a problem with the effectiveness of the treatments we have today. He puts it starkly: “the care crisis requires nothing more than a wider application of the best care we can offer.” To which I say… eh.

I am frequently pushing people who approach me with psychiatric crises to get into care. I have told people to “go in” more times than I can count. I truly believe that currently-existing psychiatric medicines save a lot of lives, and for the fortunate, they can relieve several kinds of pain. Contrary to what many skeptics believe, the majority of people who pursue treatment for mental illnesses eventually achieve stability and remission. In August I will reach five years of continuous medication for my bipolar disorder, and there is little doubt that being medicated has saved at least the quality of my life, and perhaps my life itself. But.

You have the continued, widely-lamented lack of efficacy of antidepressants. I am convinced by those who argue that SSRIs offer real improvements, but they are small even in the rosiest analysis of the data. You have frequent arguments that most psychiatric drugs are really just sedating, that they do not address underlying conditions and instead merely incapacitate to the point that those conditions can’t surface. (I strongly disagree that this is the case with antipsychotics, but that doesn’t mean that they are fixing any core problems, either.) You have the dependency and addiction issues that are common to these drugs. You have the weeks it takes many psychiatric drugs to build up in your system before they take effect, which is a major problem during a crisis. And you have the truly ruinous side effects that these drugs come packaged with, which help explain why adherence to treatment is so poor. Beyond medication, you have ever-percolating controversies over whether therapy works, or which kinds, or whether the kinds that do can ever be adequately scaled. We all know people who have been in talk therapy for years without any clear indication that they are improving, or any specific sense of what improvement would look like.

So I’m not sure that the situation is as simple as an access problem for effective treatments. Neither is Insel, apparently, as he eventually layers on enough qualifications and exceptions that I more or less agree with him. It definitely dulls the fire that he brings when he first insists that we have the tools we need, but then again I get the desire to present things that way, given the national scandal that is our terrible failure to provide access to treatment to the mentally ill.

I will now inevitably give the book’s second half short shrift. That’s the solution half, the prescription to go along with the description. That’s the important part, to many people. I’ve already previewed it for you a bit: Insel thinks that we need to truly implement community-based care of the kind that was imagined but not achieved with the Community Mental Health Act. Insel correctly diagnoses a system that only intervenes in emergencies, only in pieces, and without anything like adequate follow-up care or infrastructure to return people to functioning life. (With mental illness this is somewhat in contrast with drug addiction, where there’s at least some degree of functioning intermediary system between detox and civilian life, although of course not equitably or inexpensively distributed.)

Those three Ps - people, or a connection to those who can provide support and accountability; place, which yes means communal spaces that provide structure but also literal places where people can undertake the healing process; and purpose, or something for the mentally ill patient in treatment to work for, a sense of working for a greater good than simply “getting better.” If this sounds a little loosey-goosey, Insel peppers it all with references to real programs that have had good outcomes in various places, and does keep an eye towards the horizon of “precision medicine,” the failed dream of treating the mind by learning about the brain, as well as about genetics. All of this will take money, taxpayer money, as well as easing of various regulatory burdens, a more evidence-based approach to therapeutic techniques, and evidence-gathering that contributes to greater accountability about what works and for whom. Insel’s portrait of a more effective and more humane system of psychiatric medicine is a remarkable document overall, something worth working towards.

And this is where the cynic in me says… and a poney.

I’m not trying to be a jerk, or fatalistic. I think we are capable of vastly better than we’re currently providing. We have to do better than we’re doing. And as Insel repeatedly says, the current system is inefficient as well as frequently ineffective, and in the long run many of these reforms could pay for themselves by saving money on incarceration and residential care. But simply in terms of getting the dollars we need, federal and state and private, the lift will be enormous. Nor is it easy to unwind the tangled thicket of state and local laws and practices, which often vary tremendously from place to place. Insel stresses the need for education and awareness, which sounds great, but by whom, and where? And since it’s 2022, he says that the movement to reform mental health must get on board the social justice bus. There’s just a lot of demand here, and when Insel analogizes the problem to environmental issues, I think the comparison is apt in ways that don’t help him and which he may not intend. The kind of whole-planet, we’ve-got-to-change-everything philosophy of environmentalism referred to here seems no more likely to actually be achieved than Insel’s dreams.

In the final chapter, in the midst of calling for profound changes to policy, funding, and philosophy, Insel says gravely that “America as a nation of ‘I’ needs again to become a nation of ‘we.’” Sounds simple! I like the ambition. I admire the plan. I could not be more on board with the necessity. But Insel’s book, while a lovingly prepared and deeply humane text, often feels like it could just as well be talking about how badly we need to bring community mental health to the Moon.

Several readers have asked why we haven’t been doing open threads lately. Pretty simple: I just forgot. Expect an open thread this weekend. Sorry about that.

For anyone interested in the de-institutionalization era of the 60s and 70s, I recommended The Great Pretender by Susan Cahalan. She set out to write about a famous study (published in Science Magazine as On Being Sane in Insane Places) where a psychologist, David Rosenhan, and some other students he recruited, got themselves admitted to mental institutions although they had no existing or documented mental health problems. The results of the study showed that after having to “prove themselves sane” in a Kafkaesque nightmare to be able to leave, they came out with more mental health issues than they went in with and horrific stories of their treatment. The problem? As she researched, she found out the whole thing, a study that greatly influenced the move to deinstitutionalize, was almost certainly faked and that most of the pseudo patients it was based on never even existed.

Thank you for bringing attention to the deinstitutionalization problem. It sends people to the jails and prisons (LA County Jail claims to be "the nation's largest mental health facility" -- http://shq.lasdnews.net/pages/tgen1.aspx?id=TTC ), but also to the streets. An enormous amount of the "homeless problem" on the West Coast is a mental health problem and/or a self-medication with hard drugs problem.