Ryan Zickgraf was one of two runners up for our Book Review Contest, and here is his entry. Check out his Substack, The Third Rail. Congratulations to the winners and thank you to everyone who participated.

The dress Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez wore to the Met Gala in September functioned as a societal Rorschach Test. The commentariat class and social media users battled over their interpretations and reactions to the New York congressman sashaying down the red carpet with “Tax the Rich” emblazoned on the back. Did The Dress prove that AOC was a genius, a revolutionary, a pariah, or a sellout?

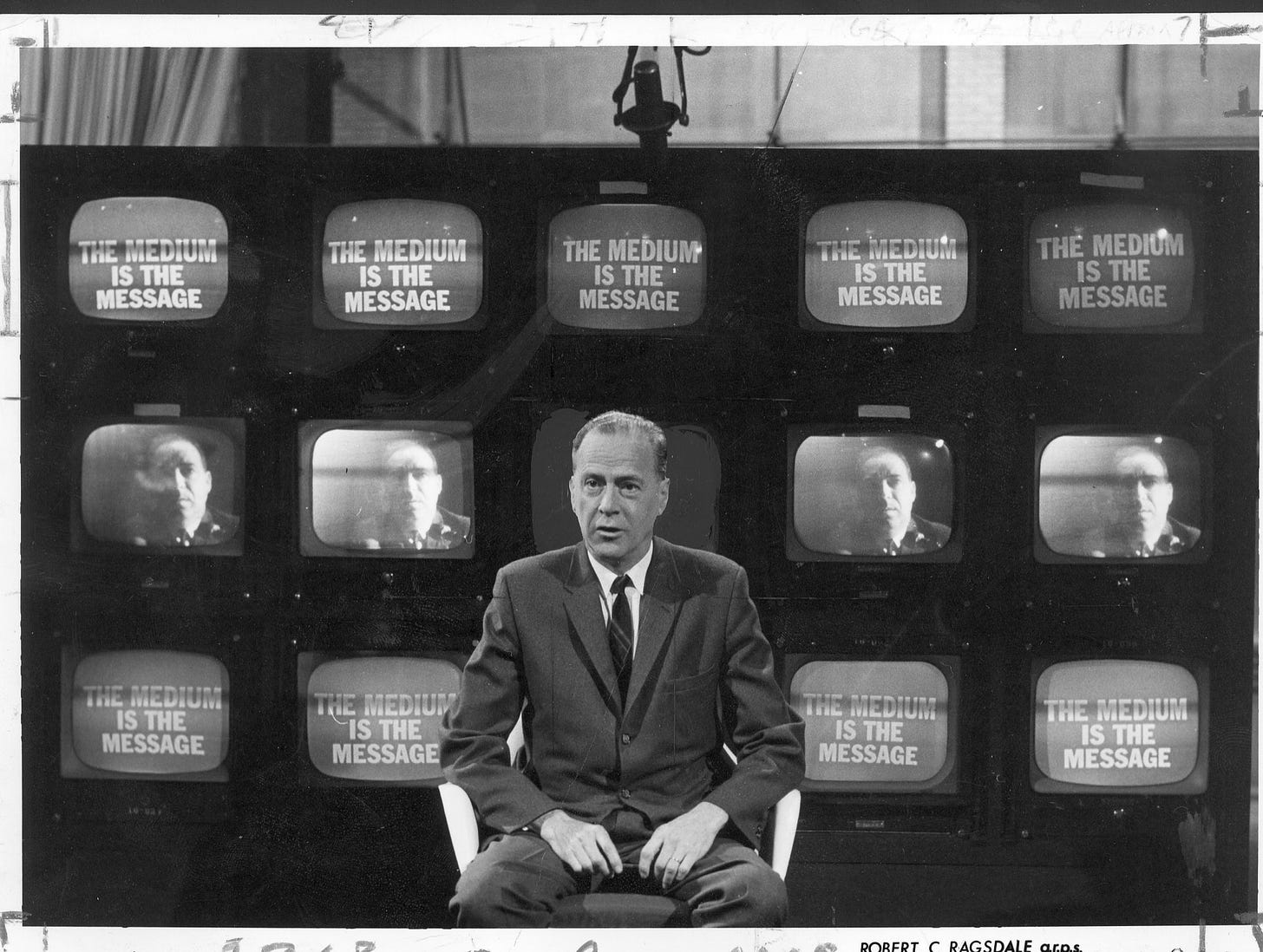

Ocasio-Cortez’s personal take, published on Instagram a day later, seemed to suggest the outfit was a subversive act of persuasion, a kind of guerilla marketing campaign designed to promote the idea that rich people need to be taxed more. “The medium is the message,” she wrote in a post liked by 2.3 million people.

That line, Marshall McLuhan’s famous maxim, was originally meant to be literal, the opposite of Bill Gates’ slogan that “content is king.” Content, thought McLuhan, was merely window dressing for the psychic and social consequences imprinted by the instruments that broadcast the information, whether it be radio, telegraph, telephone, or television.

“The medium is the message” got turned into a metaphor posthumously, which is exactly what the media guru’s disciple—Neil Postman—suggested in his 1985 polemic Amusing Ourselves to Death. He thought McLuhan's line was a little extreme. Modern advertising and marketing industries pared it down even further, now deploying "the medium is the message" as a pithy way to mean: “the medium through which a message is delivered is profoundly important to how the content of the message will be received and parsed by its consumer.”

All of it is rather amusing when you consider that the AOC dress pseudo-event was predicted in McLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage a half-century ago. Well, sort of.

Squint hard enough and you can see The Dress' ancestor in a full-page spread from the 1967 book, On one page: a black-and-white image of a woman in a mod dress with the word “LOVE” sewn in block letters side-by-side with a seemingly unrelated photo of a politician making a speech in front of an American flag-bedazzled podium. “When information is brushed against information...the results are startling and effective,” reads the text underneath. “The perennial quest for involvement, fill-in, takes many forms.”

McLuhan’s cryptic words could double as a synopsis of his own career arc.

His body of work is a kaleidoscope of art, culture, technology, and media theory that grew more colorful and playful over time. In the ‘40s and 50s, he embodied what you might expect from a mid-century Cambridge-trained literary scholar—a dour Catholic and racist reactionary who loved James Joyce and hated Hollywood. His early writing cast plenty of stones at the emerging mass culture industries.

“Blondie and her children own America,” he wrote about the newspaper comic strip in 1944, “They control American business and entertainment, run hog-wild in spreading materialism into education and politics.”

His first book, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man, published in 1951, fretted about democracy dying in the darkness of lowbrow entertainment: “Either we penetrate to the essential character of man and society and discover the outlines of a world order, or we continue as flotsam and jetsam on a flood of transient fads and ideas that will drown us with impartiality.”

But something interesting happened to McLuhan’s intellectual development in the early ‘60s: he loosened up and got cool. In The Medium is the Massage, McLuhan compares the sensation of the shift in his perspective to the way that the mariner from the A Descent into the Maelström coped with his ordeal—by adapting an emotional detachment towards the vortex and appreciating the beautiful way it was destroying everything around him.

“His insight offers a possible stratagem for understanding our predicament, our electronically configured whirl,” he wrote.

In other words, McLuhan had stopped worrying and learned to love the bomb of pop culture. But unlike the harrowed seaman from Edgar Allen Poe's short story, the experience of adapting to the fury of the media maelstrom didn’t age McLuhan.

Quite the opposite, in the years following the publishing of his breakout book Understanding Media in 1964 he blossomed from an obscure academic crank into a rock star public intellectual and a hero of the counterculture. The next year, Harper’s had already deemed him “Canada’s Intellectual Comet” and Tom Wolfe wrote a profile for New York that led with a riddle: “Suppose he is what he sounds like, the most important thinker since Newton, Darwin, Freud, Einstein, and Pavlov?”

In the same month that The Medium is the Massage was published in 1967, McLuhan was packing lecture halls and appeared on the covers of Newsweek, and the Saturday Review. Imagine an anti-Jordan Peterson, a Canadian professor who got mega-famous after he got woke. His rapid ascent and crowning as the Oracle of the Digital Age rankled his colleagues in academia, who dismissed him as a “whimsical sociologist” or worse, an ad writer whose five minutes of fame would soon be up.

But oh how spectacular those five minutes truly were. The Medium is the Massage was McLuhan at his Beatles’ "White Album"-era apex—and like the Fab Four, he seemingly invaded all forms of media. The print edition took the most quotable portions of Understanding Media and mashed it together like a collage stuffed with offputting photos of eyeballs, typographic tricks, illustrations, and New Yorker cartoons. The goofy backstory of the title of the book was that it was a mistake, a printers’ typo that McLuhan kept because "massage" instead of "message" sounded provocative.

The Medium is the Massage also got made into an experimental Columbia Records sound-collage album produced by John Simon that featured oddities like a crowlike voice squawking out, “The medium is the massage! The medium is the massage!” over and over. McLuhan's work also somehow became a psychedelic hour-long documentary on NBC that plays like a '60s counterculture version of Adam Curtis’ similarly confounding BBC documentaries.

In some circles, namely amongst the techno-optimists of Silicon Valley, McLuhanism never really died—he’s still considered a visionary that knew that tech and new modes of communication would turn the world upside down. The problem is that many of his modern-day apostles treat his wisdom like they're eating it at a cafeteria and only pick out the parts that coincide with their world views.

Part of the fun of revisiting the source material in 2021 is that it's like digging up a time capsule for navel-gazing Boomers filled with prophecies for today—half of which are prescient; half utter bullshit.

The weakest stuff is what sold well on Madison Avenue, McLuhan's philosophical boosterism for emerging tech made by IBM, GE, and communication companies. Screens would save us, he thought. Five decades later we know it was closer to the opposite effect. Similarly, television didn’t increase participation in world events—as McLuhan predicted—electronic tech didn’t kill individuality, and the airplane didn’t make cities and highways disappear. McLuhan’s utopian vision of a global village united by instantaneous free-flowing information where we’d feel each other's pain? Nope, everyone hates each other online.

What holds up best is his darker and contradictory visions of the future of media and a digital society. He proclaimed computer networks would erase privacy (“one big computerized gossip column that’s unforgiving and unforgettable” is the best summation of Twitter I’ve ever heard) and decades before anyone used the term "identity politics" posited that identity would be defined by individuals within themselves; less so by society externally. McLuhan was also right when he predicted that electronic mass media would slowly kill religious faith: "Christianity definitely supports the idea of a private, independent metaphysical substance of the self. Where technologies supply no cultural basis for this individual, then Christianity is in for trouble."

Hell, McLuhan even predicted Ronald Reagan’s presidency. He predicted that politicians of the new mass media era would have to be warm, folksy, informal types with game show host personalities, men like Will Rogers or Jack Paar. If he’d lived longer, it would have been interesting to see if he could have foreseen the rise of AOC, a young telegenic politico who has perfected the dark arts of the still-relatively new medium of social media.

Today, he’d probably suggest that the blood-red “Tax the Rich” slogan printed on the white dress was simply a distraction, ”like the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind,” as he once wrote. What he’d obsess over: if a dress can command the media’s Eye of Sauron-like gaze better than a televised speech, or anything else, what does that say about the rest of us?

Regardless, the fact that AOC’s invocation of the phrase “The Medium is the Message” got taken at face value—independent of any explanatory context—is a testament to the power of McLuhan’s original usage of the phrase. Maybe the medium is the message and all we can do is sit back and stare in admiration at the maelstrom's destruction of everything.