Some years ago I read a book called Making Rent in Bed-Stuy by Brandon Harris. It’s one of those quintessential first-book essay collections, of the type where the titular theme of the book is effectively explored and then a set of mostly-unrelated essays is wedged in to make the project book-length. My Goodreads review read “When it’s about making rent in Bed-Stuy, it’s good. When it isn't, it’s... less.” I did think there was a lot of good in the book, but I had to sift too much to find it. It’s a problem common to a lot of nonfiction, especially that which has a memoiristic bent - maintaining focus when the dictates of publishing so often prioritize padding. I thought of this issue more than once when reading Patrick Bringley’s new book All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me. Happily, he mostly succeeds where many others have failed.

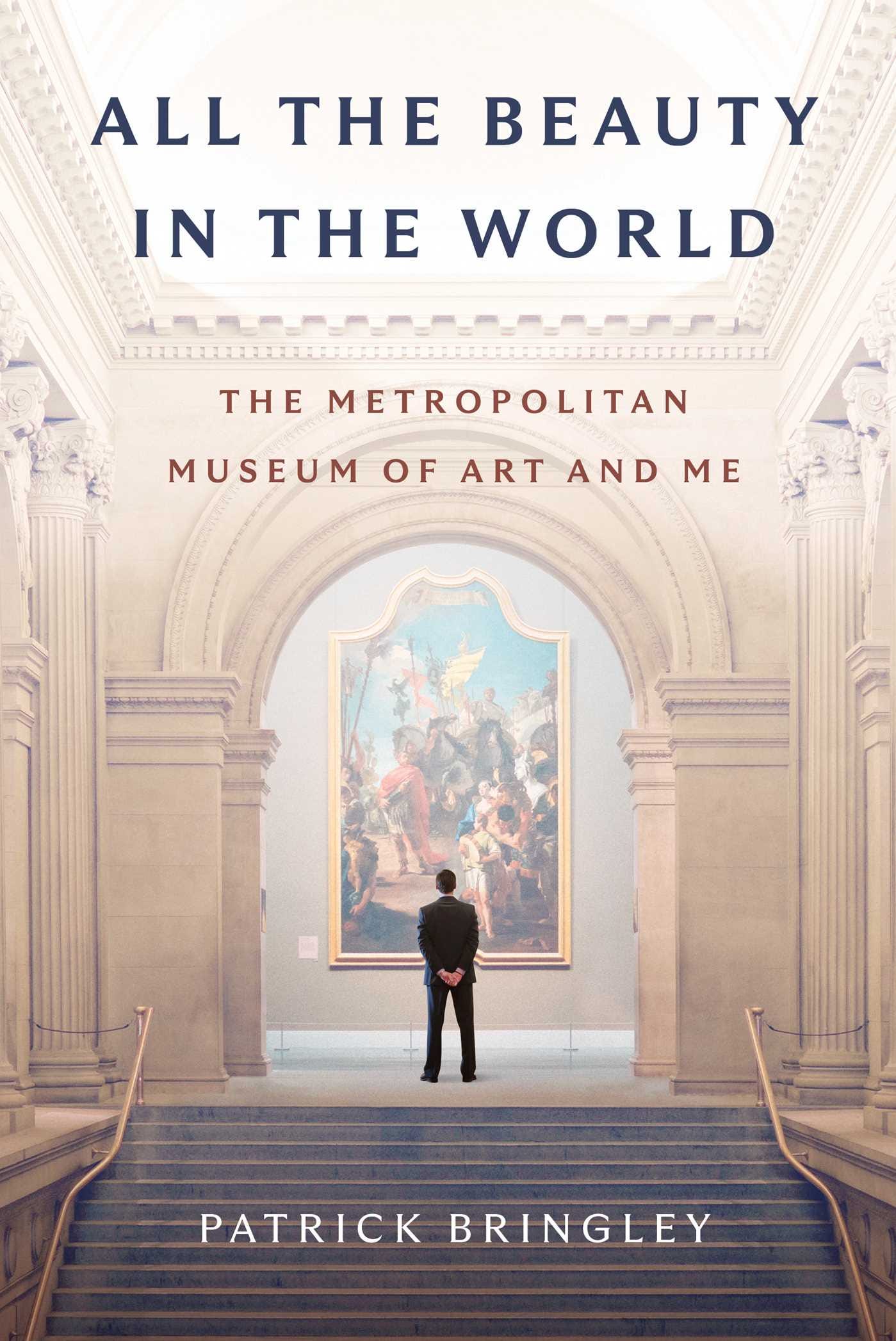

Bringley’s book, his first, tells the story of his ten years as a guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, what it was like holding down that job and what he learned about the Met and its collection. That’s enough to hook me; I love art museums in general, even though I’m not the most educated art fan, and the Met is an institution I love, one I visited at least monthly for the first four years I lived in New York City. I’m the target demographic, here, an easy sell, and unsurprisingly I enjoyed my time with the book.

The fundamental appeal of this book is Bringley’s unusual level of access to the museum and the stories he accumulated in his decade there. This is fun on a variety of levels. One level is simply an intimate look at an institution that many people have affection for but few understand on a logistical level. There’s a lot of pure behind-the-scenes, here’s-how-it-really-works information about how an immense and hugely popular art museum operates. This is obviously limited to a guard’s perspective, but that’s a useful and unique point of view of the museum. Bringley takes a lot of care to flesh out the personalities of his fellow guards, which is essential for the flavor of the book, and there’s quite a bit about the many colorful characters he met among the museum’s visitors. (This is the kind of book you read for the anecdotes.) Another level on which the text operates is as a series of ruminations on art, its creation, and its appreciation. There’s tons of little tidbits, pieces of artistic trivia that I didn’t know before reading, and I appreciate the amount of research at play here. Bringley shares which art was his favorite, what different galleries inspired in him, and how being a guard changed and deepened his attitude toward visual art. And he does it well. The value proposition of this book is obvious, and at those fundamental tasks - teaching the reader about the operations of the Met and about its art - it clearly succeeds.

The question of padding presents itself, but as I suggested, these fears mostly go unrealized. Early on, I was worried that the book had a What It’s Really About problem. Bringley writes movingly about losing his brother Tom to cancer, an event which helped inspire him to leave a low-level position at the New Yorker and take up his post at the Met. I am, obviously, not callous enough to ding a book or its author for writing about the death of a loved one. And I recognize that a brother dying from cancer is an entirely appropriate thing to write about in a book. My concern lay in the fact that many nonfiction books, again especially those that are structured as memoir, tend to become preoccupied with What It’s Really About, personal stories that take us away from the book’s specific subject matter. It sounds cruel to complain about the various tales of woe that these books delve into, but the point is not that these stories aren’t important or even that they’re poorly written; the problem is that these personal stories are inevitably less arresting than the subject matter we signed up for. The balance is everything, and many books don't get it right. (I read a book about the American bison once that had a big What It’s Really About problem.) In the first several chapters of All the Beauty in the World, I became concerned that the story of Tom’s cancer would eat the book, that stories about the museum would end up leading inevitably back to that personal tragedy.

But the book ultimately handles its connection with Bringley’s brother’s death deftly. It feels ghoulish to critique authors writing about personal tragedy, but doing so effectively is very hard; no matter what the particulars, the type of suffering the writer endured has no doubt been explored many times before. An author often has to write with exquisite care to create new insight and inspire the intended emotions. Bringley’s discussion of his brother’s illness is workmanlike and effective, sufficiently fleshed out to be moving while appropriately brief for a book about something else. A potential weakness becomes one of the book’s strengths.

What’s harder to shake is when Bringley’s reach exceeds his grasp. All the Beauty of the World has a bit of an overwriting problem. Typically, his prose is a strength, and I have few complaints about the book’s style. But fairly often, Bringley stretches for an image or a metaphor and can’t quite pull it off. I get it: these paintings and sculptures are works of immense beauty, and they inspire us to express feelings that are difficult to express. Ordinary language feels insufficient to the task. But these are the most dangerous situations writers find themselves in, precisely when we most want to find the words to convey intense emotions. And at times, Bringley falters, producing passages that sound to me like a chord played on a guitar where the high E string is tuned a half-step too sharp.

But the book’s heart remains firmly in the right place. As you might imagine, All the Beauty in the World filled me with both inspiration regarding the world’s storehouse of great artwork and an intense desire to visit the Met. Its artfully-lazy considerations of art and its meaning serve as a book-length advertisement for reconnecting with the visual arts. The museum should hand out copies. Bringley makes this endorsement explicit at the end of the book:

Come in the morning if you can, when the museum is the quietest, and at first say nothing to anyone, not even a guard. Look at artworks with wide, patient, receptive eyes, and give yourself time to discover details as well as their overall presence, their wholeness. You may not have words to describe your sensations, but try to notice them anyway. Hopefully, in the silence and the stillness, you’ll experience something uncommon or unexpected.

Couldn’t have said it better myself.

I agree that his writing doesn't quite hit the mark when describing the armor, but I I can't deny how much suits of armor have fascinated me through the years.

In fact, Bringley might have missed the obvious connection with his wondrous title. Rather than the "cold, hard honesty" he sees in Sir Giles' helm, what stands out for me is the ornamentation on all of the suits of armor I've seen in museums.

They were designed for protection and the sheer force of hand-to-hand combat. That's real and it's practical.

So they didn't need to be beautiful.

But they are. Granted I've only seen them in museums, and I imagine not all of them were for the greatest of the nobility. But the enormous effort to make them glorious stuns me every time. Same with swords and shields and armor for the horses.

Nothing says more about humanity than the fact that for centuries of bloody, gory war, people worked hard to make something beautiful for the battle.

Thanks. Now I have a book to add to my list and another reason to get to the Met.