Let’s start with zero theatrics, then spin some up over time. Because there’s no value to theatrics without sense and no reason to make sense if we don’t have fun.

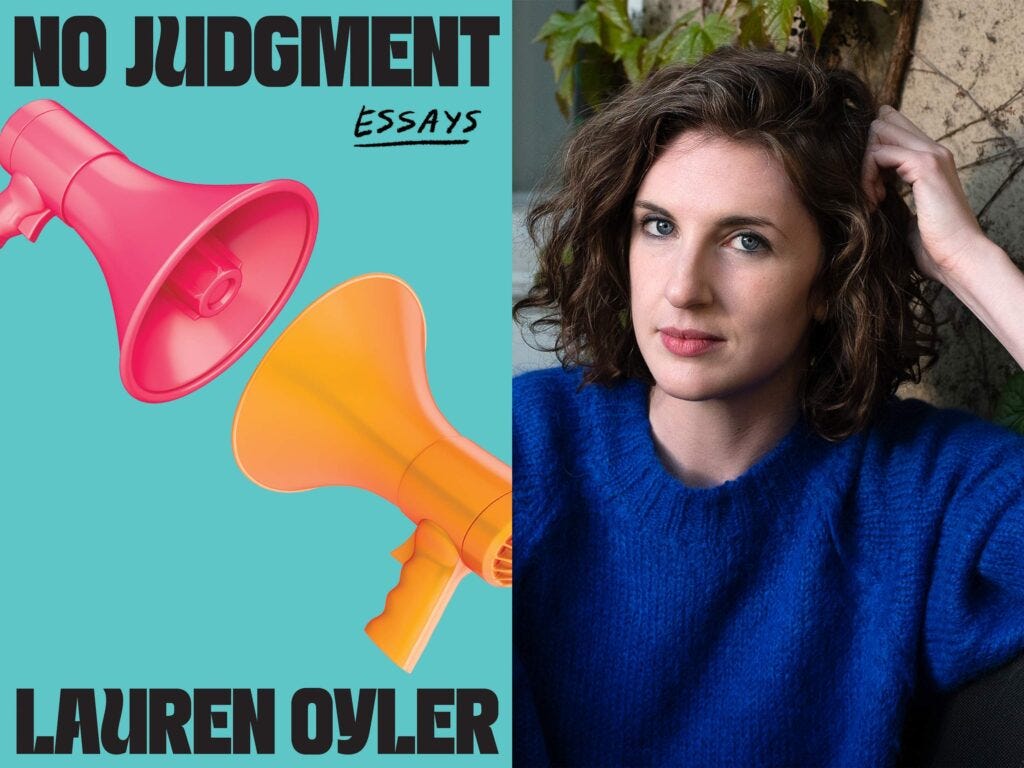

I enjoyed Lauren Oyler’s new essay collection No Judgment a lot, and I think it’s a good demonstration of growth from a remarkably talented but frequently frustrating writer. She’s kept her trademark complexity and compositional adventurousness while leaving some of the adversarial framing and self-defensive tics behind. The result is a collection that’s confident, pleasantly crabby, and never less than fully committed, even when it stumbles over its own ambitions as a work of craft.

No Judgment is a collection of six long original essays (the shortest is 32 pages) plus a brief introduction and afterwards. The ostensible subject matter of these essays include our cultural obsession with anxiety, our cultural obsession with vulnerability, our cultural obsession with gossip, and a few more things. I say ostensible because these essays are pleasant ambles, unhurried after dinner walks where Oyler picks through whatever she fancies; the Goodreads essay that everyone’s commented on already is about Goodreads, but only kindof. These pieces instead allow Oyler to bounce off of a variety of textual, historical, and (especially) social realities, giving her space to ruminate while she returns again and again to the overarching topic which concerns her, the interplay of various interpersonal dictates, how they rub against and complicate each other in ways that often foil our basic desires. This is the reason for the book’s title - Oyler makes it plain that there is no approach to contemporary life in which there is actually no judgment. There’s only public and private spheres.

The lengthy nature of the essays, and their admirable lack of haste, help to tamp down Oyler’s worst impulses, which can include a tendency to rush from one clever sentence to the next clever sentence without attending to the boring, necessary stitching that goes in between. She’s a natural aphorist - you’d want her blurbing your new novel - but in the more cramped dimensions of an essay written for a publication, her need to get all her baubles out can lead to a frenetic quality. Here, she strolls, and in general it brings out the best in her. No Judgment is neither particularly personal nor deeply researched, instead deriving its multiple pleasures from Oyler’s willingness to let attention laze around. It’s always been strange to me how we conventionally define “beach reading,” but these essays for me are ideal beach reading, in that they can be picked up and put down at whim without losing their particular charming character.

And, yes, sprinkled throughout are some great sentences, sparkling little acts of unapologetic showing off of the kind I love, alongside some of the doozies that I’ve criticized in the past - moments in her prose where Oyler tried to stretch too far, couldn’t get there, but apparently could bear to cut. “Oop, there’s a doozy!” I said a half-dozen times while reading the book. This is not as critical as it might sound. Is the phrase “I psychoanalytically remembered while writing this essay” good writing? Is “tragic pubertal developments”? Is “like a bird, my mother was scavenging for morsels”? Unclear on all counts! But surely the fact that all of these appear on the same page of No Judgments suggests that we’re dealing with a madwoman here. As you would expect, though, I will take madness over boring, rote proficiency any time. With this collection I’m ready to accept that Oyler’s occasionally going to attempt some things that juuuuuust don’t quite come together, and that’s fine. Like the bizarre artifacts you find in AI-generated art, Oyler’s doozies are an unfortunate byproduct of the stepwise process that produced the whole, and here I like the whole enough to find the flaws charming.

As is true for any reader of any collection, my interest rose or fell depending on the subject of the essays at hand, though as I suggested the loping and digressive quality made the book compelling throughout. It’s definitely easier when a topic is one that you get hepped up about, in one direction or another. The Goodreads chapter was definitely my speed. Its observations on the relationship between the site and literary culture and the authors who contribute to it were interesting, if generally predictable. The fact that Oyler is clearly chaffed about the not-universally-pleasant reaction to her first book, on that site, is something I respect; I find those who act ostentatiously unoffended by bad reviews to be much more embarrassing than people who publicly register anger. Which does not meant that it’s a good idea to always go hunting for your biggest critics. I’m someone who relentlessly looks for reactions to his own work - that’s how you get better - but even I’m not fool enough to read my Goodreads reviews. I read one single review of my first book, a fairly positive one, and felt a shiver that I have not forgotten since. I prefer to throw the rocks, there, not to be their target. Oyler repeats the common refrain that Goodreads is for readers, not writers, and this is not untrue. I am an enthusiastic reviewer there, but I confess I would also like to start Goodwrites, a site where authors review reviews of their books.

The essay in question is ultimately more about these reductive star-system ratings that have multiplied dramatically in the internet era, sets of one to five stars that help people determine what products to buy, what movies to watch, even (amusingly) what pornography to masturbate to. There’s a little history that was new to me, including the origins of such ratings in travel guidebooks written by an English woman who visited the Continent in an attempt to ameliorate her tuberculosis. But this isn’t the kind of essay collection that offers up constant little research baubles that it puts out to the reader to be admired. This book is about voice, and you will like Oyler’s or not. The essay on gossip that opens the book, for example, is a profoundly shaggy thing, dipping into discussion of Gawker and online mores and social expectations set during childhood. Oyler discusses the sadly common experience of interacting with someone who’s kind to your face but talks shit about you on (public!) social media. I’ve written at some point in the past about the writer who went out of his way to invite me out for a drink, was friendly and jocular as he complained about how fake people in media were, and then tweeted about how much he hated me days later; it was so shameless that I wondered if he was doing some sort of performance art. This is Oyler in her wheelhouse, arranging other peoples’ petty hypocrisies into a diorama and then gleefully adding her own to the tableau.

I don’t really know what to make of the essay on autofiction, as I just haven’t read enough of the stuff, although it sounds like it’s not for me. It did however include some useful pondering on the writerly life; I will say that, as is often the case with Oyler, there’s a certain degree to which she’s engaged with fake transparency, discussing the behaviors of others and revealing one or two unflattering details about herself but ultimately skittering away from real self-disclosure. The essay on her life as an expat in Berlin is fun and involves some real self-consciousness of the kind she would seem to prefer to avoid, although whether you enjoy it will depend a great deal on how well you stomach her particular kind of knowing(?) ironic(??) tongue-in-cheek(???) self-satisfaction. The essay on how anxiety became a kind of social signifier is at times sublime, but it also goes on for ten pages longer than it should. The section about vulnerability as a tool for self-interest covers well-worn territory but is perceptive and generally correct on the merits. The little afterwards thing is too cute by half. Etc. It’s an essay collection; you will make your own determinations.

Now let’s get to the bitchy gossip ourselves. It’s what Oyler would want.

Oyler made a name for herself as a literary critic, especially by writing famously mean reviews of books by women like Roxane Gay and Jia Tolentino. It’s OK; Gay and Tolentino are two of the most secure figures in this business, so don’t cry for them. They’ve both carved out comfortable spaces at tony publications and earned the respect of their peers. This also made them both someone dangerous targets to go after in reviews, but also attractive ones, for someone with skills and an appetite for notoriety. Oyler’s critical work is well-pitched for attracting the approval of a certain kind of writer, the kind who both plays according to the rules of industry comity while quietly chafing against them. Her mean reviews appear tailor-made to induce readers to say “You know, I love [Writer], but I also love this review!” These are cynical calculations but honest ones. None of this would have been noticed, of course, if Oyler were not good, if she didn’t have a fastball, and she does, a four-seamer with movement. As a prose stylist she is, to use a metaphor I’m sure I’ve used before, effectively wild. She specializes in wandering out onto a very thin wire with her complex metaphors, as if daring an MFA professor to scold her, and then smiling as she saunters to the other side. When that wire is a little too thin, as happens habitually in her writing, she keeps smiling all the way down to the sidewalk. This is a charming approach to writing, even if you’d like her to develop an appropriate fear of heights.

There’s a little bit of Nell Freudenberger to Oyler’s story. They’re nothing alike, as writers, but Freudenberger is perhaps the last writer who arrived on the scene with the same much-admired, much-resented precocity as Oyler did a few years ago. This Salon piece by Prep author Curtis Sittenfeld from, my God, 2003 is a pretty good gloss on the Freudenberger phenomenon, in particular Sittenfeld’s frank admission that the resentment he and some other writers of his generation felt towards Freudenberger was fundamentally driven by envy. Like Oyler, Freudenberger graduated from one of the varsity-level Ivies and generated a lot of press based on both her grand potential and peer grumbling that she hadn’t paid her dues. I can’t say that this is a particularly gendered phenomenon - sudden-onset literary celebrity and being the subject of professional jealousy are time-honored traditions in publishing - but both Freudenberger and Oyler appear to be living in that odd 21st-century space where people aren’t sure if it’s feminist to celebrate their accomplishments or feminist not to. Freudenberger’s moment as a litworld obsession is long gone, but that’s ultimately a good thing, I suspect. She’s still out there writing books, with a brand new one just out, and seemingly enjoying life. I wonder what Oyler’s response might be to a piece like Sittenfeld’s, written about her. Freudenberger seemed not to get it and complained about it publicly, where I’m certain Oyler would have laughed it off or professed to like it. Which of those represents the better approach for women in their position is an interesting question, but I’ll keep my answer to myself.

Oyler’s status as an object of fascination among people who like books and critics and acidic reviews was enabled by the Twitter era, a now past-tense period in which all the tastemakers were in the same place and fought over things other people had written. (Was it bad luck for Dale Peck, Oyler’s true progenitor, that his heyday was a little too early for Twitter notoriety, or was it good?) In any event, you can muscle your way into such a space if you’re talented, unafraid, and mean, which are probably the three words most people would use to describe Oyler, and she definitely muscled her way in.

I already wrote about her review of Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror, which brought Oyler to the collective attention of the small world of people who like books and the large world of people who like watching other people talk shit. It ran in the London Review of Books with the excruciating title “Ha ha! Ha ha!” and past the title there was more pain to come. That essay, to me, lies in the same position as Nirvana’s Nevermind: easily the artist’s most popular, most famous, and worst work. The fundamental problem, for me, was that the review featured such an arch tone and fussily superior perspective that the writer lost control of her literary Subaru and skidded off the snowy highway. I was one of many who came to know of Oyler through that review, but for me it wasn’t a good first impression. The review includes language like

Yet the spotty acceptance of feminism has created a loophole for women in certain spheres, like media and publishing: claiming to have hurdled sexist obstacles where there were only other kinds of obstacle, we are able to take advantage of a feminist overcorrection.

All else aside, no, the review does not go on to define what the “other kinds of obstacle” to women’s flourishing is. If forced to choose only one virtue that my writing could exemplify, expressed in one word, I would choose “evocative.” That is my most treasured target as a writer. So you’ll believe me when I say that if anyone is going to let you get away with this sort of thing, it should be me. But no, I can’t get there, with this. What are those other kinds of obstacle(s), Lauren? Why write back to front this way, like Yoda writing a term paper? To be evocative, you must evoke something. This is Oyler’s weakness, her seeming unwillingness to scrap a convoluted construction because she’s too wedded to the potential of what it could be, if the words would bend in a way she can’t quite work out in her head. But words have more tensile strength than we would like to believe, and they always arrive pre-bent.

My suspicion is that Oyler was very aware, in the LRB review, that she was going after the single most popular person in the industry, the exact kind of concern she pretends never to have. This awareness operated on two levels at once. Self-defensively, she avoided censure by draping the essay in as many layers of metatextual distance as she could, so that her review amounted to a detached perspective on her own perspective on the perspective of others on Tolentino’s perspective on the subject of her essays in Trick Mirror. Opportunistically, she took advantage of every kingdom’s secret desire to see the queen fall, and thus got a lot of zingers in there, some of them on target, some of them not. But both of these influences pushed her in a fussy, mannered direction, towards overwriting. The result is a dreadful review, but an admittedly skilled grasp for attention. It was an attempt at a takedown, and I suppose that someone or something was certainly taken down. I could just never really parse what that was, and I’m not sure the many readers who praised the review (including Tolentino herself) could either. I think a lot of people just thought “this girl is too smart for me” and clicked retweet.

Oyler never got around to critiquing the glaring flaw of Trick Mirror, its almost magisterial lack of ambition. But then, the trouble for a reviewer there is clear: it’s hard to write a vicious takedown of a bestseller that’s mostly guilty of being pretty good, of being respectable and proficient, one that earns strong reviews and makes a healthy profit without pretending to make a statement. But unlike Trick Mirror, Oyler’s review itself was teeming with ambition, was positively addled with it; that was the only part I liked. Strange then that her first novel was not. Or, perhaps, not so strange.

Advancing towards the mountain by climbing over someone else’s body is a writerly tradition. Another such tradition is other writers waiting for the one who wields the hatchet to publish their own book. A year after the LRB review, they would got their chance. Oyler’s 2021 novel Fake Accounts was not treated particularly unkindly by critics, to my memory, but certainly there was a sense of ambient disdain from many of those who had recently shared the assault on Trick Mirror. (There’s some sort of circle of life metaphor to be had here but I’ll spare you.) I personally felt like Fake Accounts needed a little more time in the oven, as like so many other first novels it reads more like an idea for a novel than like a novel. I loved the premise - everybody loved the premise - a story about a young woman who discovers that her boyfriend, by all outward appearances a docile New York City liberal, is an online conspiracy theorist plugged into a byzantine world of far-right politics. She then proceeds to anonymously crawl into that fetid world herself, obsessed, first as a horrified voyeur, later…. Well, it’s hard to say how she feels later. As I and others complained when the book came out, Fake Accounts abandons this interesting premise about fifty pages in, most obviously through the (spoilers!) death of the boyfriend. It’s a frustrating book.

You would like to know more about No Judgment! OK. But Oyler herself recently complained about the space constraints of writing for traditional publications, and I’m going to use that very thin pretext to justify the following diversion. You can feel free to skip down to the next page break.

Many people seemed to enjoy this takedown of No Judgment in Bookforum by Ann Manov, perhaps out of appreciation for the emergent geometry of this fractal pattern of ever-multiplying takedowns, an Apollonian gasket of writers shitting on each other’s work. (Meanwhile private equity pawns off the copper piping from the offices of whatever’s left of the big publishing houses.) And, look, I get that those who write hatchet jobs will get hatchets lobbed at them in turn, every lion in time a gazelle. Certainly Oyler is a more than fair target. I also can’t deny that some of Manov’s blows land. The subject matter in No Judgments does make it feel a little dated, although the whole thing with printing out and binding a book is the suggestion that what’s inside doesn’t need to be timely. Manov is indeed correct that Oyler has a disconcerting habit of following a particular stylistic flourish into a state of incomprehensibility, as I complained about earlier. And when she says “No Judgment displays many of the flaws Oyler once so forcefully identified in others,” well, yes. All are indicted, there, but that’s true.

However, the further up the ass of the English language we climb to reach a new rung of smug superiority, the higher the bar we’re setting for ourselves. And Manov utilizes a spray-and-pray approach in her review of No Judgment; her piece works via accumulation, not precision. Speaking as a man who both is and very much is not in the same business as Manov and Oyler, I think you just have to write defensively in an essay like this. Manov doesn’t, to her detriment. You have to be more judicious and more fair if you’re going to take down a take down artist. When you’re reviewing something or someone that many would love to see savaged, you see, your critical obligation to be surgical and restrained only grows. It’s too easy, otherwise, too cheap.

You can’t, for example, mock Oyler’s mentioning her Yale undergraduate education while casually informing us of your own graduate work there, nor are you in much of a position to dismiss her self-deprecation when you go out of your way to let everybody know you are sublimely unimpressed with your own achievement. These impulses self-negate for both Manov and Oyler alike, but because Manov’s review is in conversation where Oyler’s book is not, the burden of avoiding hypocrisy is far higher. Both of them are guilty, frankly, of simultaneously pulling attention to their Ivy League credentials while letting everyone know they don’t take them too seriously. I went to a “comprehensive” public university, also in Connecticut, which was not remotely competitive. (Such universities take everyone who applies, and that is how it should be.) I had a good time and I’m very grateful for my education and I could, in the way of these things, play the anti-snob card. But I would much, much rather have gone to Yale. Of course I would have. You would have to. And had I gone to Yale, I would certainly not hide that fact behind a protective curtain of self-effacement. Just own that shit, ladies, it’s worth being proud over.

Anyway! You have to play defense if you’re taking down a takedown artist. If you’re going to write this essay, you can’t allow yourself this sort of imprecision:

When a Google search reveals to Oyler that the terms are not related, she undertakes “research”—these are her words—into “historicizing” vulnerability and subsequently “discovers” that professor-cum-corporate-consultant Brené Brown’s 2010 TED Talk on the subject is “accepted as the source of the concept’s contemporary popularity.” Typically, “historicizing” a concept entails finding a “source” more than ten years old

Either Yale has a maximum allowable score on the GRE Math, or Manov was sent a very advanced copy of No Judgment, or she’s doing a thing here. But I’m afraid that, doing a thing or not, fourteen years is more than ten. Rounding down from 14 to 10 isn’t kosher. You can’t allow yourself that kind of casual factual leeway when you’re trying so hard, so so hard, to be withering. You can’t.

If you’re going to write this essay, you can’t (in the very next sentence) allow yourself to write something so incomprehensible:

Even were she not quite to begin with Saint Paul’s “strength in weakness,” Oyler might at least have discussed Freud’s concept of “original helplessness”

My soul left my body when I read “even were she not quite to begin with,” a construction that might compel a pious man to doubt the existence of a benevolent god. Writing itself shuddered to be bent into that evil shape. People always tell me that I need editing, and that’s probably so, but in a world where editors let “even were she not quite to begin with” escape into the wild like a superbug leaked from a lab, editing clearly has profound limits. I feel concussed, reading that back again. You can’t write that while you’re trying to ostentatiously shred another writer’s book. You can’t write it!

If you’re going to write this essay, you can’t allow yourself to be so uncharitable:

Then, she makes a brief foray into the Michelin star (apparently less “whimsical” than exclamation points)

They’re just sneer quotes, Ann. They’re not love. Apparently they had a two-for-one sale at Sneer Quotes Depot, because they’re fucking chockablock in Manov’s essay. I reread the offending portion of No Judgment, and I cannot conceive of someone begrudging Oyler her use of the word whimsical in that context. The discussed exclamation points sound exactly whimsical to me. And even if they don’t to you, there’s a certain level of good faith you have to extend to another writer with these things. There’s critiquing the dish and then there’s acting like you get to decide how the chef moves around the kitchen.

There’s also this motif of Oyler being a lazy researcher, of turning to trite examples. Perhaps that’s fair, but then it’s also true that pulling from a particular set of thinkers and quotes in and of itself is not superior, if you are primarily motivated by readiness-to-hand. (That’s a Heidegger reference, folks, don’t try to match me in this game, you’ll lose.) I have no idea how Manov managed to cram Cyril Connolly - Cyril Connolly!! - into her essay, but I accept it because life is too short. Manov belabors Oyler’s alleged dependence on Wikipedia in her essay, and point scored I guess. I myself, however, am just a bit too lazy to search up Manov’s master’s thesis on ProQuest to find how many of her references in the Bookforum piece make an appearance in its Works Cited list. Because while saying someone did her research on Wikipedia certainly has extra sting, the real meat of the accusation is the implication that the sources of the research are too obvious, that Oyler is pulling from a bag of tricks. Right? Yet Manov herself seems to have received a very particular education in English letters, and while she may be right that Oyler is a fake, she reminds me very much of those academics who spend a career rewriting their dissertation.

Mostly I think the Bookforum piece is a missed opportunity, as Manov allowed her clear personal disdain for Oyler to overwhelm what are some genuinely cutting critiques; her essay is too aggressive in intent to achieve true aggression in effect. She should have given the devil her due, if only to take it away again. Were she more charitable she would be less. Manov says, as a summation, that Oyler has “spent too much time thinking about petty infighting and too little time thinking about anything else.”

Perhaps. But now, darling, you’ve done the same.

My own mean essay would simply point out that Oyler has spent too much time building a writerly persona and too little time writing. She needs to produce more. Of course, personas get press and press gets advances. But at some point I think she has to decide if the doozies are something she’s doing on purpose and are here to stay, or if they were a necessary part of a younger writer working out her own style in full view of an audience that glommed on to her because of her undeniable talent for talking shit about people who are more successful than her. Part of the trouble is that there now are few out there who are more successful than she is, at least in the particular world she’s in. And No Judgment seems like the work of a woman who’s grown bored with hyper-articulate bitchiness.

My other complaint is one that I’m not easily able to put my finger on. As I alluded to above, there is a sense in which Oyler is hiding the football while engaging in a style that seems self-effacing. There’s nothing confessional about her work in any terms related to self-disclosure, but her essayistic voice lives in a state of superposition between utterly untroubled superiority and a sly acknowledgment that this is all a bit and she’s just a flawed, down-to-earth woman who’s doing a character. Fake Accounts drove me nuts with this. I’m well aware that the narrator of a novel is not the novel’s author - unless it is, a possibility that Oyler contemplates in her usual tidal style in the essay on autofiction. She invites the consideration, in her writing, in that her nonfiction authorial voice is omnipresent and constantly betrays palpable worry about how it sounds to others. She writes, “The natural voice of a writer should be a bit more literary, a bit more refined, than the average person’s, shouldn’t it?” I may not be able to identify autofiction. But I know a confession when I hear one.

This lack of commitment to either superiority or cagey vulnerability will have consequences, moving forward, if she decides to keep doing hatchet jobs. There is no more rising up from obscurity, for her; she can no longer hide in the shadow of the literary world’s disappearing celebrities as she chucks her rocks up at them. I hope she’ll choose to be rigorously honest about the fact that, whatever her stature, when she takes another writer down, she does so from a level playing field. I’m not trying to be arch here. I don’t know, I guess it just feels sometimes like Oyler is trying to gussy up plain old bitchy judgment, taking her reputation too much into account as she slaps a layer of self-effacing paint on her desire to scald, like the meta-social morality of one of those women who take sexy pictures for a living but are the type to dress up as the Rocketeer or whatever in their photoshoots. (That metaphor may need some workshopping.) Better to keep doing what she’s done in No Judgment, which is to write a book that is relentlessly curious about the social worlds in which she lives, but which is not itself an effort to maneuver herself in that world, as her early reviews so plainly were. It’s a good book, one that habitually spins a little out of its author’s control but which never ceases to offer a genuinely unique authorial voice and a persistently endearing desire to play in words. That playfulness is a rarer quality than anything else on offer here, and it is enough.

Someday, Oyler will write a book from a state of antique and purifying defenselessness. Inshallah, it will be soon.