This is the third post in (the first annual?) Lit Week at freddiedeboer.substack.com

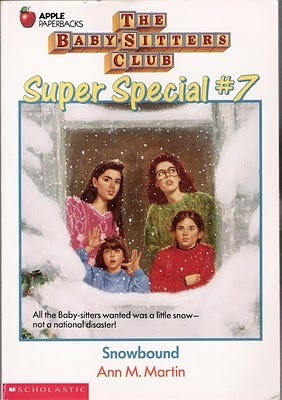

Baby-Sitters Club Super Special #7: Snowbound is a tweenaged grindhouse nightmare of positive attitudes and minor stakes, a book that dares to ask “What comes after just now - the jubilee and terror of an unmarked world, the misery of being stuck with our indelible selves, or the worst of both at once?” Somehow both frenetic and narcotizing, this tale of the female id set free from the bounds of our still-Victorian mores by several feet of snow both entrances us with the possibilities of wymxn’s liberation and horrifies us with its assertion of the inevitability of phallic power. The girls long to be free of the patriarchal constraints imposed on them by an uncaring society, one which now showily critiques the male gaze but which still seeks The Eternal Daddy at all times for love, validation, protection, and sexual recompense. But these young firebrands, these six avatars of the American Sehnsucht, embody in their collective identit(y)ies what we might call the misandrist barbaric yawp. As much as a seminal 1970s issue of Lesbian Connection magazine, as much as the Bumble profile of someone who writes for Teen Vogue, B-SCSS7SB conveys the femxnxne sublime, the post-male imagination… and its limits.

(I warn you that this one went, perhaps, a little long.)

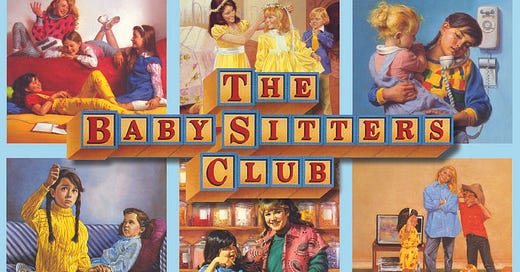

The Baby-Sitters Club series is of course the creation of “Ann M. Martin,” a figure who like JT Leroy both exists and does not, and in so doing troubles our conception not only of the author, but of the very meaning of authorship. A ghost, a cypher, a vessel for the collective unconscious, a woman made so fabulously wealthy by the first three dozen or so of these goddamn things that she could pawn the job off on someone who was willing to do it for a flat fee with no royalties - who’s to say, really, who this “Ann M. Martin” really is? Perhaps, in a way, she is all of us, if we had all grown immensely wealthy by coming up with the avante garde premise “what if some girls did babysitting?” Well, in her honor, let’s do what she forced so many of us to do, which is to skim through the same laborious bullshit explaining the characters and story to date in all 213 of these fucking books.

Who could, at this stage, not know the basic story by heart, imprinted as it has been on the great quilt of the human experience? Young Kristy, heart torn by the divorce of her parents and possessed by a need to hold ultimate authority over other children, gathers a murderer’s row of girls with brown hair to her ambitious startup, a dream team of babysitting skills/having implausibly dramatic but relatable problems. (Eventually they added three new girls to move more merch in the key blonde, Black, and ginger demographics.) With chilling efficiency, they take over the Stoneybrook market, achieving monopoly power and working relentlessly to crush the competition, Bezos-like. The rival Baby-sitters Agency sought to resist the totalizing force of Kristy’s ambition and met the same fate as Diapers.com. Our girls are thus free to undertake a series of babysitting adventures in which they live, laugh, and love their way to greater maturity and understanding. Along the way they wrestle with prickly siblings, nagging parents, boys who just don’t understand, and Stacey’s crippling cocaine habit. (They may have cut that last bit out for the Netflix show.) For a generation of young readers, these girls showed what it was like to survive The Struggle, specifically the struggle of being high-achieving upper-middle-class children from stable families living in a tony suburb on the western Connecticut shore.

Questions abound - Does the BSC pay taxes? How is it appropriate for an 11 year old to supervise three young children? What kind of tween babysitting cartel needs five fucking officers? - but “Martin” feels no need to answer these quotidian gripes; she plays with the very concept of “making sense,” and introduces these brain puzzlers simply to accentuate the unheimlich. Truly we are dealing with a maestro here. I tip my cap to her as well as to the sweatshop workers who actually wrote these.

Like “Martin,” we must begin our efforts by giving each major character their intro.

Oh, Kristy. You’re clearly gay.

Leader of the BSC and certified #BossBitch, Kristy’s aggressive exterior masks a heart that yearns to let free her unbridled tribadistic passions. Here’s a passage from Kristy about her boyfriend Bart. (Bart is the most “made up boyfriend” name I’ve ever seen.)

I have a friend. I mean, a friend who’s a boy. Oh, all right. He’s my boyfriend. I guess. I never thought I would have a boyfriend. My friends say I’m a tomboy, and I suppose that’s true. I love sports. I love wearing jeans and running shoes. Basically, I think makeup is a waste of time. And jewelry? I can take it or leave it. I don’t even have pierced ears. However, I met Bart. Everything changed. No, that’s not true. Bart and I met because we each coach a softball team for little kids. So our friendship is founded on sports. Also, I would still rather wear blue jeans than a dress.

What a true-to-life jumble of the head and the heart! Larry Kramer never captured the queer experience with such efficiency. When was the last time you read such a sympathetic portrayal of the confusion inherent to the closeted soul? These are the words of a girl at war with herself, one who can’t quite state the obvious but can’t fully live the lie. Kristy struggles to balance the conventions of a conservative society with the reality of being a woman who’s just a little too into softball. Not all tomboys grow up to be gay, of course, but Kristy is making-out-during-“Building a Mystery”-at-Lilith-Fair gay. Kristy sublimates her desire to live her truth by being aggro and blunt, the kind of person whose curtness and social clumsiness are destined to make her seem bitchier than she really is. I see her future as a beloved middle school gym teacher whose “special friend” comes to all of the field hockey games she coaches. Her brute directness and lack of social graces makes her the perfect strongman to lead an organization of such unbridled ambitions as the BSC, like Imelda Marcos in her greed, Thatcher in her iron will, and 2000-era Rosie O’Donnell in her towering ambition and not-fooling-anybody closeted deal. Also when I read these I pretty much imagine a 13-year-old Rosie O’Donnell and that’s Kristy. (Not Christina Ricci. Kristy wishes.)

Mary Anne. The boring one, but also the most crushable? (Please remember that I was like 8 when I started tearing through these books like a… like a weirdo 8 year old boy reading his older sister’s 125 Baby-Sitters Club books.) Mary Anne’s story is an accelerated bildungsroman, as we watch her transition from girlhood to very-slightly-older girlhood. As the series begins, she quietly suffocates under the heavy burden of her father’s overbearing parenting, inspired by her mother’s untimely death. But by saving the day, in a book imaginatively titled Mary Ann Saves the Day, Mary Anne proves her worth and in so doing persuades him to loosen the reins. This newfound freedom is visualized in her taking her braids out and literally nothing else. I guess she also probably bought a couple chunky sweaters and some sassy barrettes or whatever. This all happens in book four of a 200+ book series and yet remains the most relentlessly-cited element of Mary-Ann’s personality, so you get a sense of what we’re working with here. Like so many things in this tangled chronology, Mary Anne’s “transformation” from someone who wears skirts that hang an inch above her ankles to someone who wears skirts that hang three inches above her ankles somehow just happened like yesterday across the entire run of this vast series. Still she was always that hot one in my head and as I would ride the bus to middle school I often imagined fighting Logan Bruno for her love. But we shall get to Mr. Bruno.

The good news is that Mary Anne is not, at this point in the continuity, rocking that goddamn hideous bob. That’s the kind of haircut you get when you’ve just moved to some sad exurb to be closer to your dipshit husband’s mother and you have to pretend you like it there.

Ah, Claudia Kishi. Forever the effortless cool girl. A fashion icon of the pre-Instagram era, you were always everyone’s favorite, which is not hard to be when the other three are about as spicy as single-serving Jell-O. Claudia’s iconoclastic clothing styles have inspired a cottage industry of internet analysis, but the series takes pains to show that her expressive style and popularity with the boys does not obscure her fundamental insecurities. (For some reason Claudia is always portrayed in the various filmed adaptations as sassy and confident. Drives me crazy. Claudia is not sassy!) Her academic struggles and frequent clashes with her conservative Japanese-American parents only serve to make her more endearing.

Of course, Claudia is never portrayed alone; her presence always constitutes a diptych. For a spirit rides forever alongside her - the spirit of her sister Janine. In Janine we are presented with the archetype of Asian American achievement, the model minority made flesh. Wherever Claudia breaks free from the imposition of Western imperialist ideals of meritocratic success, or of “correct” spelling, Janine appears in spirit if not in form, an eternal reminder that culture narratives of hard work and success are like a, uh, certain kind of finger trap - the harder you try to pull away, the tighter the expectations constrict. Janine, with her exaggerated bowl haircut and equally exaggerated drive for academic and personal success, presents to Claudia an uncanny representation of the path not taken, one that she cannot bring herself to pursue… but also cannot fully reject. It is for this reason that I propose we view Janine as a Tyler Durden figure, an expression of Claudia’s id come to life, no less real for being unreal, a portrait of the sublimated conflicts of a whole class of person. Also like Tyler Durden she’s probably taught Claudia how to make explosives out of human fat.

“Which way, Asian wom!n?,” seems to be the author’s demand. The question we the reader must ask ourselves is this: does “Martin” here curse Claudia and all of the other young Claudias out there, the American Asian girls who must navigate triple consciousness (Asian, yt-adjacent, middle aged white lady from the 80’s conception of being Asian-American) to a prison of fractally-multiplying identities? Or does she seek to set them free? Which wolf inside of Claudia will win?

A figure of both natural sympathy and an avatar of all that you find annoying, Stacey is the most desperate to show that she’s unique and thus the most ordinary of any of our girls. Though these books exist in a timeless land we might call the Forever Now, it’s also true that Stacey was born before her time; she was made for the social media era. She grew up in New York City and won’t let you forget it, to the point that today she’d probably put #nativenyer in overly-composed Instagram posts of some three-months-past-cool NoHo eatery. Stacey would be a lock to put #queer in her Tinder bio despite never participating in anything but cishet encounters. Like Claudia, Stacey is a fashion obsessive who uses clothes in an effort to distance herself from, well, from white-bread ass girls like Kristy and Mary Anne. But Claudia and Stacey’s dynamic is a classic trope of the natural and the tryhard. Claudia is no queen bee, as her insecurity and quiet kindness don’t fit that archetype. (You got that, Netflix? It’s bad enough that you forced the phrase “social contract” into the first five minutes of a show about tween babysitters.) But Stacey, somehow, is still clearly her lieutenant, the beta girl. Claudia is effortlessly herself; Stacey tries to appear not to be trying. Stacey’s fashions are both more restrained than Claudia’s and yet more effortful. She lacks Claudia’s unfussy kookiness and substitutes for it a forced adventurousness she can’t quite fully commit to. Damn, Stacey! “Quirky” oversized pink sweater with garish appliques and black and white checkered tights? That’s almost interesting. You can have a Madison Avenue background, sweetie, but some girls make it look like hard work while girls like Claudia fall into the jumper craze 30 years before it’ll be cool. I feel for you, I really do.

However, Stacey has an ace up her sleeve, in that the team of Vietnamese textile workers who wrote most of these books gave her two whole personality traits. She also is diabetic, and she has to give herself daily insulin shots. You will read about this again, and again, and again, and each time it will be presented as a crazy curio, like she’s got chronic Lyme or something. How many times can we read about her struggle over whether she can have that cupcake or not? (Key to understanding this series is that the creators know most people will grow out of it after twenty books or so and are therefore shameless about going back to the same well.) Let me put Stacey this way: the fundamental driving force behind her arc in Snowbound is that she needs to get to the mall so that she can get a perm.

Also when she “rescues” the autistic girl like halfway through the series, good lord. Just wear a t-shirt that says “ALLY” and be done with it.

“I’m from California” isn’t a personality, Dawn.

Into this sea of mayo-ass characters swims Jessi Ramsey - confident, graceful, determined, academically inclined and yet not all tryhard about it. Like a figure out of Toni Morrison’s portrayal of the Harlem Renaissance in Jazz, or perhaps an extra in A Different World, Jessi showcases a Blackness that is both defiant and unfussy, a lived-in and authentic sense of self that cuts against the various mannered ruses that constrain the yt w*m3n of Stoneybrook. Jessi’s dancer body reflects the lithe and limber character any Black woman must possess as she bends to accommodate the yt gaze.

But while her Blackness absolves her from contributing to the overbearing whiteness of Stoneybrook in the way her wypipo+ colleagues do, Jessie is portrayed as a girl divided. Her undeniable BIPOC credentials stand in sharp contrast with her unmistakable pursuit of white adoration. Note her best-friendship with Mallory, whose ytness is so intense and piercing it outshines even the snowblinding radiance of that of the series as a whole. Ginger, with skin so pale it’s almost mint green, Mallory hangs as Jessie’s psychic imago of the Caucasoid imaginary. Mallory’s large family contains (to our horror) a set of red-haired triplets, who can only be a portrayal of the Weird Sisters of Macbeth - gender swapped, of course, for in the Zone-like narrative enclave of Stoneybrook (a brook, strewn with stones like the rivers of our lives are strewn with regrets) no straight thing can go uncrooked-ed. Surely Jessi has been possessed by this Trimurti of white innocence. But if her friendship with Mallory can be excused the way we might excuse an aphid for following the bidding of a parasitic wasp, how can we explain her obsession with ballet, an artform so white it forces her into tutus of Crayola-pink, the only color whiter than white? Truly this is a brutal portrayal of the Mephistophelean bargain all young Black women must face, the shame of assimilationism against the pains of rejecting all that they once knew. I’m guessing she goes on to make a big show of considering going to Morehouse (edit: Spelman, sorry I mixed up my HBCUs, in my defense I'm extremely white) before taking that offer from Stanford. But can you blame her? She didn’t make this racist universe, “Martin” did, and Jessi’s gotta collect scholarships and awards as she starts her long journey to that Stuyvesant Heights townhouse. Don’t feel bad, Jessi. Secure that bag.

Hello, Satan. We meet again. I’ve hated Mallory since I was a child, which is especially impressive given that she is granted all the personality of a wet sock in this series. Mallory’s character traits include the fact that she a) is ginger, b) has red hair, and c) is carrot-topped. We might go so far as to call her auburn. That’s about it. Oh, and she comes from a large family and is frequently annoyed by this fact. Like Jessi, at 11 years old she seems far too young to me to be regularly caring for multiple young children on her own, but then the 80s were a different country. Looking back I have no idea why Mallory annoyed me so much, and I apologize if she’s your favorite. Luckily she’s so bland she kind of fades into the background, a ginger spirit who occasionally throws her hands up in resignation as one of her 17 brothers pees on her leg.

For the record none of the above really applies to the batshit alternate continuity of the Friends Forever offshoot, starting with Everything Changes. Here are some actual quotes.

Kristy: Abby and I are having the best time at camp. I'm SO glad she's here. LOVE getting to know her better.... I walk with Abby and steer her to our table, help her load her plate, etc. She's more helpless than the campers... but I find it endearing…. Abby is such a sleepyhead in the morning... I lean down to her bunk and sing, right in her ear...

Stacey: Going to a party in the middle of the week, especially a party with no adults present, was just so... freeing. Tomas's parents were going to be away for several days, so he invited people over. We stayed up late drinking coffee and listening to guests read poetry.…

Claudia: Let me bake up.

Mary Anne: Ever since the fire [Logan] has been so overprotective of me. It's driving me crazy. It's almost as if he WANTS me to cling to him. To need him. And he seems hurt when I don't. But... I'm doing just fine. How can I convince Logan of that? I must think. I don't want to hurt him. But I have my life to live.

Oh, right, the plot.

As we open our tale, Stoneybrook hangs heavy with anticipation: our intrepid young babysitters, like all decent people, yearn for snow, to cavort in and to wash their sins away and most importantly to cancel school. Our heroes long to wade across the frosty landscape untroubled by the burdens of ordinary life, dipping their feet in snow like amoretti treading God’s own clouds in the great works of the Quattrocento. Yet though the weatherman assures them again and again that salvation is coming, their hopes are repeatedly dashed, leaving them stuck in a liminal state and gazing at a future yet unrealized. They are anticipating the upcoming middle school fete, provocatively named the Winter Wonderland dance, which inextricable binds together the opportunity to meet their fellow pubescents in a mimicry of adult courtship with the brute physical realities of the seasons, of winter, the earth’s long slumber from which rebirth inevitably comes and yet which leaves all of us contemplating each year the grave possibility that this time, spring will not come. For now all they can do is simultaneously yearn for snow and fear it, dreading its awful power while daydreaming about its infinite possibilities and the lives not yet lived.

(The snow represents adolescence.)

And yada yada yada, some stuff happens. Stacey begs her mom to take her to the mall to get the aforementioned perm, Kristy plays grabass with Bart, we’re forced to read about Dawn’s little brother despite the fact that we care about him even less than we care about Dawn, Jessi hangs out at dance school with some extremely lame kids, and there’s some bullshit with a missing rat. “Martin” has contrived to pair off each of the BSCers with an appropriate boy partner for the dance - don’t worry, I’m sure in the remake Stacey’s date will be two-spirit or whatever - and you can feel the 1991-era IBM beige-box novel-writing AI really struggle to come up with these characters/plot devices. For example, Jessi’s date is named “Quint,” surely a common name among Black 11-year-olds in early 1990s suburban Connecticut. Claudia’s date is called “Iri Mitsuhashi,” and trying to suss out just how racist that is seems like a task beyond this humble reviewer. Indeed, we are frequently treated to the authors’ elegant grasp on race relations, with sentences such as “Let me see. Oh yes. One other thing - Mal is white and Jessi is Black.” Smooth.

Baby-Sitters Club main series books are told from the vantage of whichever girl is starring in that one, and the Super Specials rotate around chapter by chapter. A major part of the lazy pro forma construction of this interminable nightmare of a series is that each chapter starts with a diary entry written in the distinct handwriting of each girl. As a 40-year-old man I find I am now less charmed by trying to read that goddamn chicken-scratch “real” writing at the front of every chapter, though I appreciate the care that went into matching the font to the kid. Kristy’s, for example, I find quite butch. Mallory puts a goddamn cat face in her signature like some sort of sociopath and Jessi has the cursive of a 19th century aristocrat. As is typical in this series in Snowbound Claudia’s spelling difficulties sort of wander around in intensity to suit the moment. Sometimes she just drops a silent letter or two; sometimes she’ll write (as in Claudia and the Perfect Boy) “Staduesk butey sekes cule guy for fun daytes,” which to me says less “distracted 7th grader” and more “traumatic brain injury.”

So anyhow before the snow comes Claudia is watching a few bullshit kids and their annoying dog, Mary Anne is watching Mallory’s bullshit family, Stacey has been on this drive to the mall with her mom for what seems like six days, and Dawn is waiting for her brother at the airport, and her sections of the book are just about exactly as much fun as waiting at the airport. All of this is set up to provide maximum drama when the snow falls, which we know it will because everyone in the book keeps going “Snow? Yeah, right!” And then it does. So much snow! A blizzard. More even than in Baby-Sitter’s Club Super Special #3: Winter Vacation. That book is vastly inferior, but does provide us a glimpse into the depths of Stacey’s addiction. Check this out.

Ah, “the bus ride is bumpy” excuse. I bet you’d like to get snowed in, wouldn’t you? Look Stacey if you want to snort your babysitting money straight up your nose I’m not stopping you, but let’s have some integrity here. You see where she decides to drop a little bon mot about the population of Hacksett Crossing? This is an example of what I call “cokehead storytime,” which is where someone who’s overindulged is under the false impression that everything that comes out of their mouth is infinitely interesting and will proceed to inject such facts directly into your brain, relentlessly, like a sniffling Terminator. Get help, Stacey. And dump Laine. It’s been awhile but IIRC he’s like 24 and it’s not appropriate, even for a native New Yorker.

Anyway - the snow falls on peaceful Stoneybrook like a quilt of icy possibility, rendering the world afresh and obscuring our broken earth’s sins enough to permit the dream of something better. Our girls are freed from all of it, from parents, from expectations, from social mores, from the neverending challenges of a thankless world. But most of all, from boys. In the steady agglomeration of white flakes, the patriarchy is obscured, just long enough for the BSC to contemplate a world without men, without their complications, their crudity and their insatiable appetites, their temptations. Briefly, so briefly, a new world opens to them and in so doing expands their consciousness, sort of like when Picard becomes a genius for a little bit in the last episode of Star Trek The Next Generation. Yet into this sapphic wonderland comes, inevitably, the intruder, the male presence which not even the pristine opacity of the post-blizzard landscape can hide: Logan.

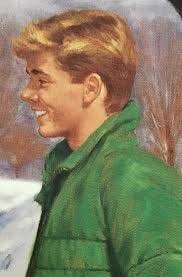

Ah, Logan Bruno. He haunts the series like some ancient WASP spirit, his very existence defined by the impossible perfection of his jawline, his smile, his tasteful green parka. In B-SCSS7:SB, Logan’s absence in the early chapters means more than the presence of any of the other characters. Like Ahab, he drives the action even through mention, through rumor, the raw force of his personality so hypnotic and powerful that the book seems to fear to allow him to coalesce into his blonde actuality. But coalesce he must, because he is the representation of the phallus, the commanding God-Man authority who reminds us of the unyielding presence of the male gaze and its power to rip even this temporary winter innocence from our budding young feminists. Also Logan is everyone’s favorite and like half the people who read these read them for the rare glimpse of Logan, which is fucked up and clearly an example of internalized misogyny. On the other hand, just look at him. What a dreamboat. He even pulls off the Foghorn Leghorn dialect they force on him. (I feel like they give him that in some of the books, but that could just be a false memory implanted in my brain by my pills. He’s almost mute in this one.) The wiki says Logan is a “careful shopper,” which I will puzzle over for the remainder of my days.

Also can we talk about something? You see that goddamn LL Bean model 26-year-old-looking motherfucker in the green there? This is also supposed to be him:

I’m tempted to call the cops on Mary Anne for robbing the cradle. This child is a child! That’s not Logan! That’s not lantern-jawed Logan, the Southern gentleman who stole thousands of pubescent hearts! That’s not the same guy. This is some loser with his bullshit skis. Nice jeans, bitch.

Perhaps Logan’s bifurcated representation, his status as both man-boy and boy-man, is designed to divert away the inappropriate attention he has long received from bored wine moms who steal their kid’s books. Either way, “Martin’s” pen is true. For though Logan hangs Kurtz-like across the imagination of this book, his corporeal actuality is not as a menacing receptacle of untamed masculine power, but as the flaneur, a picaresque character who slides across the snowy landscape as effortlessly as he clearly slides through life. Logan’s ease in life, the blessing of the patriarchy and his impeccable hair, remind us that though vv0^^3n will someday at last drive us men into the sea and free the world from this hell we’ve created of it, boys are cute and sometimes they ski through a blizzard to bring us food.

Sorry that I’m not doing a better job of following the various throughlines of the plot, but in my defense it’s a poorly-constructed slapdash collection of anodyne stories about tweens facing the absolute minimum amount of danger from a snowstorm, which is a natural disaster so frightening people regularly daydream about experiencing one in a cottage in the woods. Helicoptering in to find whichever BSCer is yet again reassuring some pampered child who has reached about a 3 on a 10-point anxiety scale is not my idea of a rollicking adventure. And this fucking thing is a tonal nightmare, let me tell you. There’s a real asymmetry to the plights of our characters. Like, Claudia’s story involves chasing after a dog who’s a real rascal! Also Stacey and her mom might literally die. Jessi is like “how can I comfort this wealthy horse girl who’s inconvenienced by being trapped at her elite New England dance academy?” and Stacey and her mom are eating ketchup packets to survive. I have to hand it to a book where “but Logan will see me without my makeup!” and “please don’t let me freeze to death in a Subaru at 13” are given equal emotional weight.

Anyway it snows, they persevere in the face of a series of totally unthreatening made-up dramas, Kristy accomplishes nothing but does so looking like a leader, Dawn sucks, Logan makes all the girlies go wild, Stacey eats her mom to survive, Claudia’s spelling somehow gets worse, and in the end they all go to the dance and presumably dry hump to Paula Abdul’s “Rush Rush” on the dancefloor, the end.

But for me, Baby-Sitter’s Club Super Special #7: Snowbound will never end, for I have not escaped its emotional event horizon in the 30 years since I first read it. It entrances me, this vexing tale, and it will until the end of my days. For only “Martin” could capture a dream-world vision of such eldritch horror:

I opened my closet and gazed for awhile at the red dress for the Winter Wonderland Dance.

That night, I dream of snowflakes and carnations and Bart. In the dream, a storm hit Stoneybrook. Only it snowed fat white carnations, which showered down on Bart and me.

I am haunted by these words.

Guys, is this literally the greatest thing any of us have ever read? Because I'm thinking yes.

Wow. That was.... wow.

I hope you get a groveling apology from the guy who complained about Lit Week.