Things I Read

a unranked, unsystematic, partial, random list of stuff I read that deeply influenced me, which inevitably leaves off many I'm not thinking of and many others I wish to keep secret, known only to me

Wizard Magazine circa 1991-1995, by various. I would buy it at the Neon Deli. First got issue #6, with a Sam Keith painting of the Hulk on the cover, I believe. It became my first exposure to a certain kind of insouciant humor that I still feel fondness for despite the internet having ran that style into the ground. In time I would read much more of Wizard than of the comics that they ostensibly covered, and then I would reach high school and I moved on to other things. But it was very important to me during an impressionable time.

The Ethics of Ambiguity, by Simone de Beauvoir. The most important book I have ever read, I think, still. The most humane, the most human. Certainly, from my estimation, the most livable and most compassionate expression of Sartrean existentialism. The kind of book that you fall in love with for both the things it reveals to you, and for its fierce dedication to reminding you that you are not learning anything to set you apart from any other human being. (Sorry if that sentence is hard to parse, but it’s the best I can do to approximate what I’m trying to say here.) I am in love with Simone de Beauvoir’s mind, and I am quite sure I will love it for the rest of my life.

Witch Week, by Diana Wynne Jones. An immensely entertaining, incredibly true school story that taught a 10 year old kid who might have been inclined to go the Holden Caufield route that there is no romance in being a scorned genius. It's a meditation, compassionate and fair, that at once brilliant describes the endless cruelty of childhood social divisions and how outsiders are divided from the pack for ridicule, and yet refuses to make that awareness an excuse for those outsiders to turn around and hate the mass and worship their own genius. (Charles, co-protagonist with Nan, is a genuinely unpleasant character in a way I truly respect. I also empathize with him to a disturbing degree.) I remember, in middle school, realizing that the unpopular kids could be just as close-minded and image obsessed as the popular kids. (And then, in high school, marveling at how much everyone had matured and had grown to be good to one another.) Jones reminds us again, in this book, that the only way forward is understanding and empathy for all of us, not just for the self-identified underdogs - of whatever variety. No one was like her and as much as her books had run out of steam near the end of her life I miss her terribly.

Silent Garfield/Garfield Without Garfield’s Thought Bubbles, by the crowd

For the record, way, way funnier than Garfield Without Garfield.

On Truth and Lies in a Non-Moral Sense, by Friedrich Nietzsche.

Once upon a time, in some out of the way corner of that universe which is dispersed into numberless twinkling solar systems, there was a star upon which clever beasts invented knowing. That was the most arrogant and mendacious minute of “world history,” but nevertheless, it was only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star cooled and congealed, and the clever beasts had to die. One might invent such a fable, and yet he still would not have adequately illustrated how miserable, how shadowy and transient, how aimless and arbitrary the human intellect looks within nature. There were eternities during which it did not exist. And when it is all over with the human intellect, nothing will have happened.

I still believe in a better and fairer and more compassionate economic system and I’m a believer in the power of ideas and I am still, in a way I feel utterly uninterested in explaining to anyone, a communist. But there is a part of me that has, over time, given up on a certain faith in grand historical narratives and totalizing ideologies and the clash of civilizations. All hope for humanity lies in individuals; the question is whether those individuals can discover the value of solidarity. I do believe in the power and value of the romantic ideal, and in human happiness, and grace. I also believe that we are born in fear of death and we live in fear of death, though I think if we are lucky we can die in peace, surrounded by friends. And I suspect that those who believe in a human consciousness capable of accurately rendering the world around them in its totality do so in denial of death. But perhaps you’ll have to read my second book someday to get a little more of what I mean.

Incidentally - it it hard for me to imagine a more fundamentally morally troubling figure than Nietzsche among those who have been widely read and digested. It's truly bizarre to me that people want to banish Heidegger to the realm of the forbidden books, but keep Nietzsche around. Nietzsche out-Nazis the Nazis; Nietzsche feels towards most everyone the way anti-Black racists feel towards Black people. That near universality of his derision is not somehow an excuse for that derision. It makes it all the worse. Nietzsche is a brilliant, necessary monster, one of the worst in the history of the intellect. It should go without saying that this doesn’t mean I think his books should be banned; I think for this very reason they should be required reading.

The Holy Bible, and who it’s by is controversial. One of the most profound testaments to the capacity of humanity for incredible compassion, and its preference instead for bloodshed and hatred. Some terrible theology, some fantastic mythology, some brilliant adventures, some awfully turgid prose, some of the most delightfully weird, brilliant, unexpected moments I have had the pleasure to read. (Like Mark 14:51-52.) A brilliant mess. I read the Revised Standard Version.

Our Fantasy Football Website, the (private secret password-protected) message board of my high school friends and our fantasy football league. Started in 1992, my fantasy football league is old enough that our commissioner Zman (two years older than me, my older brother’s grade) used to hand score the games by reading the box scores out of the newspaper. Our website, a classic internet forum, is in its current incarnation about 17 years old. Naturally, most of it is not about fantasy football at all, but about politics, movies, food, current events, and memes. It’s been a way for a core group of 15ish people - OK, 15ish dudes - to stay in close contact years after we moved on from home. Some people have Something Awful, some people have 4chan, some people have Reddit. I have this.

The Fountainhead, by Ayn Rand. Much more important than Atlas Shrugged, for my own development. Atlas Shrugged left me, predictably, full of righteous indignation, certain of the terrible moral corrosion of Rand and her project, sickened by her greed and self-obsession, and generally repulsed. Repulsed I remain, I suppose. But reading The Fountainhead, eventually, became very important. For the first, I don't know, half of the book, I was feeling the same way, and the ideas remained just as screwy and the prose just as bad. But turning through the hundreds of pages gave me time to realize that hating Ayn Rand and those who follow her would be to succumb to exactly what I thought, in my righteousness, I was opposing. Whittaker Chambers wrote that reading Rand raised the specter of the Holocaust, and it does, but over time I have come to find that it also raises the specter of Rand's desperate need, her plain, palpably wounded self. Those wounds are among the most understandable I can imagine: she suffered terribly under the weight of Stalinism and anti-Semitism. That she couldn't ever come to see the similar weight of poverty, need, and fickle chance was indeed a major character flaw, but few of us are perfect. I am, to put it quite mildly, frustrated by her contemporary acolytes, for having none of her historical exposure to oppression while maintaining her desperate callousness. But we all have need. Whether I do violence to her, or them, by extending my (limited, frequently forgotten, certainly self-serving) compassion is a question I am very open to discussing. Regardless, I present this entry in part in protest against those who pretend that we only can or should be influenced by those with whom we broadly agree. I am a socialist and I think other socialists should read the Fountainhead.

The Bridge on San Luis Rey, by Thornton Wilder. This beautiful book.... A favorite of my father's, and of his mother. A meditation on earthly tragedy and heavenly compassion. I think that, if we can't help being atheists, as I can’t help being an atheist, it is incredibly important that we be atheists who understand God's love.

Leaves of Grass, by Walt Whitman. My first love, in poetry. It inspired me to read other poets, and eventually, though it would have been sacrilege to me to say so at one time, to leave Whitman behind. Not that I'll ever leave this book, or could. It's in my DNA now. But I have come to understand that I came to Whitman exactly when I needed him most, and as much as I might want to, I can't go back to being the young man I was. I used to get what I would call my Whitman bubble, where the acceleration and energy of his work would fill me up, and you feel a bit like you want to burst.... Made me an “English” guy, in the naïve and sweet undergraduate sense, and remains my constant defense against myself, when I feel like a poseur or that I'm pretentious for being too into books or whatever. I think back to hiding Leaves of Grass in my algebra book and I laugh and say to myself, “I'll be a parody, then!”

The American Scene, by various. A group blog by heterodox conservatives, where I discovered favorites like Noah Millman, Daniel Larison, Alan Jacobs, and James Poulos. Weirdos with weird vocabulary and weird concerns and strange religious commitments. I learned a lot. Eventually taken over by a bunch of people I didn’t really vibe with (no offense) and dead for four years now. A relic from a time when the internet was interesting and interesting people were on it.

Wild Girls Club: Tales from Below the Belt, by Anka Radakovich. My dad was reading this book on vacation when I was 13 or 14 and he laughed so uproariously that when we were home and he was done I sneaked it out of the bookcase to read it myself. (I say that I sneaked it because it was about sex and I was embarrassed, not because it was some sort of caper, it was just sitting there on the shelf like any other book of his that I wanted to read.) And I laughed so hard to and was amazed at this new world of adult humor and sex. Books had been funny before, but never that funny, and never about that subject. I also, I don’t mind admitting, found Radakovich very hot and she became one of my first sexual fixations. Maybe ten years later I pulled the book out to see how it felt to read it again, but put it back pretty quickly. It didn’t hit the same - Radakovich’s humor has been replicated and refined a thousand times over online, so it didn’t seem fresh, and anyway that was one of those perfect storm experiences. I still thought she was incredibly hot though.

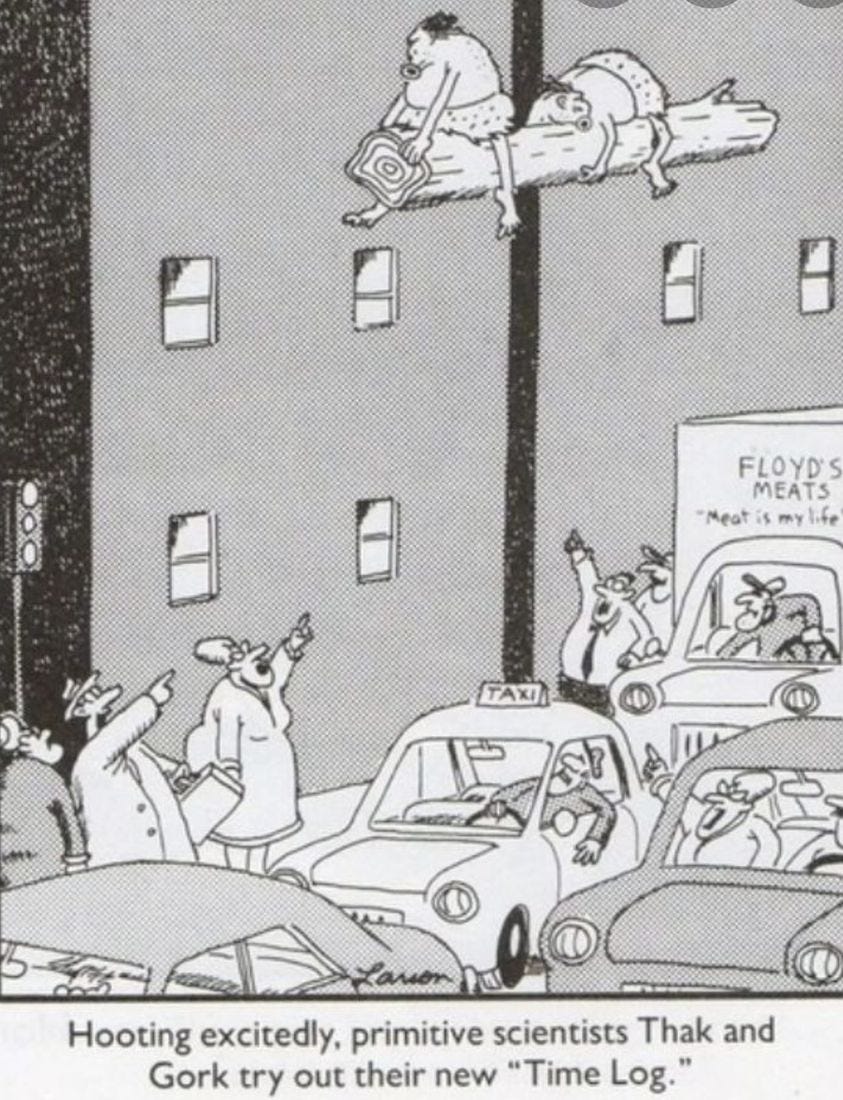

The Far Side by Gary Larson and Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Watterson.

These were the two comics I was obsessed with from late elementary school to the end of high school, and I had good taste, if I do say so myself. Nowadays I see a lot more to admire in the former than the latter, mostly because the absurdity and subversion of The Far Side just strikes me as a rarer commodity than the sweet-snarky combination of Calvin and Hobbes. (In part, of course, because Watterson’s comic was so immensely influential.) I would come to learn through reading the Prehistory of the Far Side and the Calvin and Hobbes 10th Anniversary Book that Larson was sweet and thoughtful and Watterson was… well, a dick. I also, over time, have come to recognize the preachiness and sentimentality of a lot of Calvin and Hobbes. (For example.) But I can’t deny I loved it, and still love some of it, or that it is head and shoulders above The Far Side in terms of art. I suspect that it’s in the visual dimension that Watterson will ultimately be the most influential. Either way: these were titans for me.

Once upon a time, kids, you got up in the morning and read the newspaper for comics.

Deep Wizardry, by Diane Duane. My Goodreads review is about as good as I can likely do here:

… it guts me and it always has. I've said for years and written many times that there's a basic metaphor that YA lit is filled with: magic as a stand-in for puberty and the frightening and powerful introduction of sexual energy into our lives. Magic takes the place of these frightening and awkward aspects of our identities, giving young people a risk-free way to think and feel their way through the choppy waters of adolescent sexuality. Like magic, sex is powerful, mysterious, and a force seemingly beyond our control, connecting us to the parts of ourselves that are animal, that are the product of evolution.

Deep Wizardry plays with this dynamic masterfully. It also spells it out more or less explicitly, as the main character Nita is confronted by her mother to ask whether she and the male lead, Kit, are having sex. But even aside from that thread in the story, the connection between the physical and the magical are made real in this story. Both Nita and Kit take on the form of whales, although through different means, given that they are two different kinds of wizards, Nita naturally talented with the living world of plants and animals, Kit with the inanimate such as metals and rocks. When they take on their whale form, they find themselves in unrecognizable bodies, bodies that they struggle to understand and control. They are thrilled by the possibilities their new bodies represent even as they are disturbed by the potential consequences of that power. They exult in the freedom of life beneath the waves while craving the safety and comfort of shore. They are growing up, and they are afraid.

There is just something so bone deep in this book, so primal and real. Nit and Kit agree to an adventure without really understanding the stakes, and when they are revealed to be deadly, they are already committed to what they must do. The ancient and otherworldly shark Ed speaks to the danger and looming power of the ocean, and his weird but profound respect for Nita is a highlight. Our heroes must take part in an ancient ritual, the consequences of which are life and death itself.

Every day of their adventure they must leave their whale forms and emerge to the surface, as naked as the day they came. Safe again inside swimsuits and towels, they emerge onto cool sand beneath the summer sky, walking into a familiar world that is not familiar at all, facing not just the reality of reality but the pains of adulthood, the bittersweet remembrance of the childish things they left behind.

A book that reminded me, as a young man, that I was a corporeal, physical being, and that I had to balance all of my dreams about magic against that. In time I came to realize just how absurdly dominant thoughts of sex and thoughts of death are in the human condition.

The Revolution Betrayed, by Leon Trotsky. The already powerful will always use that power to keep it, and to keep you from having it, and the most brilliant turn they ever made was to call it “the people.” I am a romantic at heart, and I have never quite been able to abandon old Lev Bronstein. It exposes me to criticism, but then I will never please the socdems, the demsocs, the Marxist-Leninists, the progressives, the neoliberals, even the Trots. Remember, Freddie: you can be totally committed to the relief of material need within an ethical, freedom-promoting framework, and still wake up one day to find your comrades have filled a gulag. Never forget that.

My Brother John’s Homemade Morbius Comics, by my brother John. When I was 11ish Marvel comics came up with this group of supernatural-themed comics called the Midnight Sons. The initial team-up, called Rise of the Midnight Sons, was transformative for me. (I particularly liked Darkhold: Pages from the Book of Sins, a very non-comic booky team of paranormal investigators; the collection of the series is worth looking for.) As was the way with all comic books I ever read, eventually everything collapsed into bullshit as creative teams moved on and new ones felt no pressure to continue prior stories and the famous philosophy of “the illusion of change” meant that there could never be genuine drama…. However, we still had the comics, in particular a few issues of the Morbius rebrand - Morbius was a goofy vampire character from the 70s who was retooled into a Grim & Gritty for the 90s all-star for Midnight Sons. It was really over the top with a neo-goth style that presaged the Matrix by six or seven years. Anyhow, my brother cut up the comics and made them into new stories with all-new goofy dialogue, such that the curse Morbius was trying to fix was not vampirism but venereal disease. Good, good times.

Being and Time, by Martin Heidegger. Baffling and brilliant. I don't understand Heidegger, although I try, and I've read more popularizations, condensations and explanations than I care to admit. An necessary reminder of the ultimately very narrow confines of my own intellect. I would never claim to “get” this book, or most of its arguments. Heidegger was a genius, and I am not, and that's what this book reminds me of, but it also hints and flashes at real transcendence. Heidegger's Nazi apologetics, in contrast to this book, inspired me into a kind of blank dread, once. Kierkegaard wrote about a monk who lived on a mountain and drank nothing but dew, then went down into town one day and became an alcoholic. Very good is never very far from very bad, I think, and we live on that precipice.

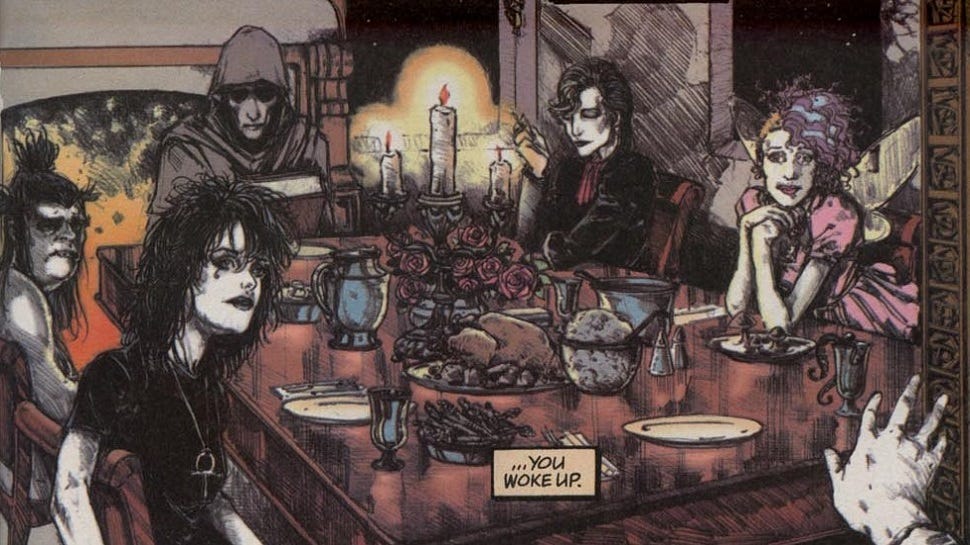

Sandman, by Neil Gaiman. Another “you can’t go home again” classic, when I attempt to return to this series I inevitably stop for fear of doing too much harm to what are still cherished memories. Looking back now I can’t deny that there’s something deeply adolescent about the whole thing; it’s Tumblr: The Graphic Novel.

But then, I was an adolescent back then, and it moved me so, and the art is often gorgeous, especially the brilliant covers by Dave McKean, and for every ham-handed self-parodic moment, there’s one of true beauty. And I can forgive my inner angsty goth teenager. I hate it when people look back at the music they liked when they were younger and make fun of it; it was the right music for you when you were the person you were then. When I was a teenager, Sandman was right for me.

The Atlantic/The New Yorker/The New York Times/Slate/The New Republic/The Washington Post 2002-2004, by the defenders of freedom and right thought. Never could I have a more formative political experience, on the level of partisan politics, than the run up to the Iraq war. Every day, I would read liberals in liberal publications rail against the antiwar coalition (the internationalist left, the noninterventionist right). I read the accusations - of anti-Americanism, of support for Saddam and his dictatorship, of cowardice, of Islamism, of insufficient support for liberal values, of apathy towards war crimes and genocide. Every day, for months. I learned pretty well how this media of ours works. I learned pretty well.

Be Here Now, by Ram Dass. Important on multiple levels. The first is my surprising embarrassment at respecting other ways of knowing - I tend to worry, “eh, they'll think I'm some New Agey person!” if I cite a book like this. Which is unfortunate of me, and unproductive. (To this day, I am more likely to invoke Richard Alpert, former Harvard psychiatrist, than Ram Dass, who he became.) The book itself is interesting, because of how plain and non-navel-gazy a look at consciousness and yogic/Zen/New Age thinking it really is. Also, it is a necessary reminder to me that I am not my intellect. RIP.

The Tin Drum, by Gunter Grass. A great, anguished, primal scream of a novel. Grass's critics can't help but seem incredibly small after you read it. Not fun to read, or easy, but necessary. On the level of ideas, explores the essential tension between the absolute prohibition against collective punishment and the absolute necessity, at times, of collective shame. I don’t care if Grass was moral. His art is moral.

A History of the Siege of Lisbon, by Jose Saramago. Once my favorite novelist, Saramago demonstrates so well that novels can be completely serious, and truly great, without being portentous, depressing, or pessimistic about the human condition. Saramago is the essential, effortless refutation of a certain kind of narrow-minded and pinched critical perspective I associate with a specific critic I will not name. This book is delicate, smart, funny and alive. It always reminds me of an amazing line from Thomas Hardy's “Convergence of the Twain:”

And as the smart ship grew/ In stature, grace and hue/ In shadowy silent distance grew the iceberg too.

Picasso at the Lapin Agile, by Steve Martin. A whip-smart work of short drama, Martin’s play is funny and sad and pretentious and poignant and doesn’t take itself too seriously, except when it does. The “No pun intended!” “No pun achieved.” exchange is so perfect I’m amazed people didn’t think of it earlier. A lovely little diversion. I’ve never seen it performed. I’ve never felt the need to.

Matt Yglesias circa 2006-2011, by Matt Yglesias. For good and for bad, my introduction to what blogging was and could be. I was lucky to discover him in the sweet spot - post pro-Iraq war college-aged fuckery but pre-Slate “FOLKS I AM NEOLIB” turn. Also essential because I met many people in the comments section there, some of whom I still know, now IRL, like David Shor.

Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, by Stokley Carmichael et al. Meyer Alewitz, the anti-Vietnam war organizer and muralist and my college lefty group advisor, once said to me, “The problem with nonviolence is, if you don't fight back, they'll kill you.” What became apparent to me as I grew older was that if you do fight back, they’ll probably kill you too. So I don’t know anymore.

I and Thou, by Martin Buber. Buber, the Austrian Jewish rebbe, is the perfect companion to Jean Paul Sartre, the French atheist philosopher. Buber was a great philosopher, a great translator, a great student of the Hasidim. More than anything, though, I think he was a moralist in the very best, most elevated sense. His vision of Israeli-Palestinian relations, romanticized as it might be, warms my heart and insists to me that I must never abandon hope or embrace a lazy fatalism. He reminds me that there is no ethical alternative to our central duty: to achieve peace, security, prosperity and equality for Palestinians and Israelis - and that the only way to do so is to stand naked before each other as we might do before God.

A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, by Dave Eggers. Is “because so many people hate it” an immature reason to list? Probably. Try, instead, because it demonstrates both the power of shared experiences, and their limits. Due to some biographical similarities, Eggers work speaks to me in an intimate way, and there are times in the narrative when I was literally shocked, because of how close to my own thoughts, emotions and pathologies Eggers came. But then, just as quickly, there would be a reminder of how deeply different he and I are, and that would be just as shocking. I think there's something to that, the tendency of life to show us ways in which we are very much the same as others, and then the uncanny, painful realizations of the divides. I read the hardcover, then eventually got the paper back, to which Eggers had amended an addendum called “Mistakes We Knew We Were Making.” In that addendum, Eggers describes people who have come up to him since the publication of his book and told him their own stories of loss and death, a tendency which Eggers speaks about with ample impatience. The people who have made Eggers successful, well-known and famous, apparently, did not merit his attention. It colored my perception of the book. But in time I read interviews that convinced me that Eggers did care about his readers and their experiences, and more - and this is a little weird - his sudden and deep unpopularity made me more sympathetic. I don’t know, it’s complicated. But I still think back to the book with intense feelings.

Measuring Success, edited by Buckley, Letukas, & Wildavsky. This book has one goal: to measure up and defend standardized college entrance exams, particularly against criticisms that they limit diversity and that “holistic” admissions will do a better job. It’s smart people writing about what they know, slaying a lot of bullshit liberal argumentative scarecrows. Their efforts have failed. For now. For now.

Various poems, by Leroi Jones/Amiri Baraka

Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note

Lately, I've become accustomed to the way

The ground opens up and envelopes me

Each time I go out to walk the dog.

Or the broad edged silly music the wind

Makes when I run for a bus...Things have come to that.

And now, each night I count the stars,

And each night I get the same number.

And when they will not come to be counted,

I count the holes they leave.Nobody sings anymore.

And then last night, I tiptoed up

To my daughter's room and heard her

Talking to someone, and when I opened

The door, there was no one there...

Only she on her knees, peeking into

Her own clasped hands.

In time he would, like others of his race and politics and cohort, collapse into conspiracism and anti-Semitism, and always reminded me in his later years of some old ex-hippie burnouts I grew up around, people who the era left behind. But when he was young, he had a masterful command, and wrote some exquisite lines. He was playful too - “Epistrophe for Yodo” better captures the peculiar feeling of comprehending New York City in all of its vast strangeness better than anything else I can think of. Think of him as a young man.

The Cement Garden, by Ian McEwan. McEwan's first book, and his best, to my mind, so of course he has disowned it. Merciless and understated. One of the blurbs on my copy says that the book is about “the banality of evil,” which is spectacularly, bafflingly wrong. This is a book about a great many horrific, chilling situations, for which there are no villains. If anything, the novel shows how terrible things can go with absolutely no malevolence at all. It is beautifully realized, in its ruthless concision, and it says many very accurate things about family - some of them very disturbing, some of them just true. A story that makes incest seem natural, which is distressing, which is the point; a classic of unease, a work meant to unsettle you and to remind you that the writer’s purpose is not to make you feel safe.

The Cum Town subreddit (RIP), by various cumboys. I have a hard time keeping up with podcasts but Cum Town, I think, is/was the pinnacle of the form in certain essential ways, not the least of which is/was the recognition that spontaneity is the only true criterion of what constitutes conversation, and it is conversation that people are trying to approximate when they listen to podcasts. (Which is some bleak shit.) Anyway, you don’t read Cum Town. You did once read the Cum Town subreddit, before it was nuked. Those guys were funny, until the end anyway, at which point the very way in which they had ceased to be funny caused the sub to be banned, so there was something poetic and fitting about it all. You wouldn’t think “I’m gay and my dick is small” could be consistently witty for years, and yet…. I never posted a single time, but I read (at work) and laughed and laughed and laughed.

The Tempest, by William Shakespeare. Carl Jung, 350 years before his time. Demonstrates the essential truth of a lot of Joseph Campbell's ideas, but in a way that makes Campbell's work seem incredibly small in comparison. Some of the most powerful, animal and elementary of human urges, emotions and cravings are expressed with enormous delicacy and a poignancy that can break your heart. Some poetry just reaches in and shivers. I'm not one for the cult of Shakespeare, whatever that means, and I wouldn't ever say that this play represents the pinnacle of human poetics, but I will suggest that for now, it still represents their upper bound. One day when I was 19 I was out driving near dusk on the Connecticut shoreline and I pulled my little red car over and ran out onto the beach, as grey and brown as a thing can be, and the wind was picking up, and there was one of those all-encompassing wetnesses that you could never really call proper rain, and the goddamn sound of it all, the wind and the surf, and out on the water, a single buoy-light beat its blinking way on the horizon.... And I knew in those moments that I was someone who was born old, and that all of my life I would be haunted by the inescapable, dreadful poetry of the hollow-earthed magic that we see just outside of the range of our sight, and when I read about Prospero, his book and his staff, I am afraid.

The Cult of Smart, by me. In many ways very little went right with the book’s rollout, and I never felt the feelings I wanted to about it. But I still hold it in my hands and say, I wrote this book. I wrote this book. I wrote this book.

I sometimes wonder why this newsletter resonates with me so much. There's something about being an online late-30s American who came of age opposing the Iraq War that leaves a lasting, formative mark on you. It's one of the most horrible things ever done in our name, we completely failed, and unlike some other movements we did not fail gloriously. We just failed.

And the phrases "I am still, in a way I feel utterly uninterested in explaining to anyone, a communist" and "I am a romantic at heart, and I have never quite been able to abandon old Lev Bronstein" are able to allow me to express my own political identity in a way I doubt I could have on my own. Thank you.

This sentence is why you have become my favorite Marxist writer (other than my own son):

"Remember, Freddie: you can be totally committed to the relief of material need within an ethical, freedom-promoting framework, and still wake up one day to find your comrades have filled a gulag."