I'll Be Against the Next "Good War" Too

There is one big overarching question that hangs over the Ukraine situation. It’s the question that’s most essential that we answer, as a country, for our future. So of course it has just about zero presence in the public debate. I’ll ask it anyway: why is the United States allowed to ceaselessly extend its military dominance to more and more parts of the globe, where Russia is not? Why can NATO expand indefinitely, where the United States would never allow other countries to form strategic partnerships with Russia or China? If Canada wanted to develop a strategic partnership with Russia - which is not really fantastical, given their geographic and economic entanglements - the United States would never, ever permit it. So why must Russia permit Ukraine to join NATO?

Of course, I think Ukrainian citizens should determine the future of Ukraine. But as a democratic citizen, my primary responsibility is my own country. And (conveniently or inconveniently, I’m not sure) my own country also happens to be the greatest threat to the self-determination of other countries in the world.

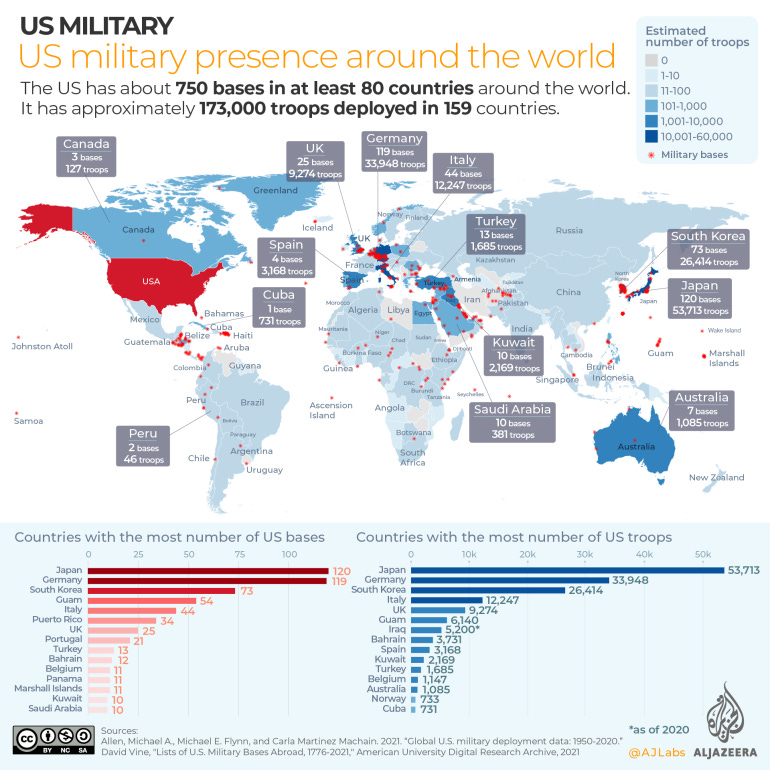

The United States has the world’s most extensive military presence, and it’s not close. There is no country on earth that attempts anything like our domination of the world. And we don’t just drop tens of thousands of troops around the globe for nothing; all of it is done to actively mold the world to our uses. We have this habit of literally surrounding our antagonists with troops, then getting angry at them for supposed aggression and belicosity. Iran had American troops on almost every flank for years and years. (Kind of thing that might make you want to have a nuclear option to deter aggression.) Russia’s border is so vast no one could encircle them, but I invite you to consider what the American western wall and Pacific stronghold might feel like for the Russian government. Does that excuse any particular thing the Putin regime does? No. But the salient question remains, and it’s both moral and practical: why on earth do American troops threaten the sovereignty of such a huge portion of the world’s territory? Would anyone countenance, say, the Chinese expanding their footprint to this degree?

“Vladimir Putin is a bad guy” is not an answer to that question. Nor is the term “whataboutism” a sufficient rejoinder to pointing out the massive hypocrisy of our country. The United States long ago declared the entirety of the Western hemisphere off-limits to any other great power, and we’ve spent centuries deposing legitimate leaders, assassinating undesirables, and crushing democratic movements in our half of the globe. And we’re lecturing the Russians about letting its nearest neighbor have self-determination? I have no illusions about Putin, who is a right-wing strongman. But we have the same moral responsibility to be consistent and avoid hypocrisy as anyone else. Sadly, the current Ukrainian government is an authoritarian regime of its own, but the Russian question within Ukrainian borders is not a simple one - last year, 41% of polled Ukrainians said that they and the Russians are “one people.” The question is not whether Putin will let the Ukrainian people determine their own future. They question is whether we are so deluded as to believe that the United States and an eventual Ukrainian puppet government would let them either, in any sort of real way.

“No one country should be able to dictate to another country what it -- what it can choose to do in terms of who it aligns itself with or no one country should be able to redefine another country's boundaries at will.”

So says Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin. Mohammad Mosaddegh, Salvador Allende, Patrice Lumumba, and the ghosts of millions of victims of American empire were unavailable for comment.

A more limited and concrete question: can the United States really continue to perpetually expand its foothold in Europe and Central Asia while at the same time acting as the counterweight to China in the Pacific?

For years now there’s been sturm and drang about China’s ambitions in the Pacific. I link to the New York Times editorial board to point out that Very Serious people, not just the usual hawks, want us to act as a check on China’s ambitions. (They are literally creating new territory to project power.) China has a billion and a half people. If they do not already have the world’s largest economy they will shortly. They’ve also got a ton of problems, economic and otherwise; there’s still 182,000,000 Chinese people who live below the relevant poverty line and they have an even bigger demographic “time bomb” than the United States. But they are a large, rich, motivated country that has obvious geographical advantages when it comes to projecting power in their half of the Pacific, and none of the other regional players are remotely militarily capable of standing up to them. (In large measure because American military largesse has made such self-sufficiency unnecessary.) If our country is really dedicated to keeping China in check, as the Very Serious People demand, can it also extend NATO protections to Ukraine and other potential applicants, given that the vast majority of NATO’s combat capacity is simply the United States military?

All of us have grown up into an American psyche that, curiously, remains convinced that our military is all-powerful. Various misadventures in the jungles and the deserts have not made much of a dent in that belief, even if most people know better than to speak it out loud. But at some point, a graying empire experiencing an inevitable relative decline and increasing competition from rapidly-advancing competitors is going to have do some prioritizing. If Israel decides to attack Iran, and China sends gunboats to Taiwan, are we really going to defend Ukraine’s eastern flank in perpetuity?

In the 1980s and 90s, hawks complained about “Vietnam syndrome,” the (ludicrous) belief that the United States had become too shellshocked by that war to project power the way we should. I see a slowly-coalescing attitude also developing regarding Iraq and Afghanistan. For example I was talking to a pretty prominent journalist recently in regards to an unrelated book project, and he was saying that he thinks our country is “hungover” from Iraq, that we learned the lesson of that failure too well. I was polite enough not to laugh out loud. We have an immense war industry in this country, and politicians love war. We have no need for some sort of external shock to get our country primed for combat.

Here's an Iraq lesson that people don't want to hear: good intentions do not equal good outcomes. Events do not comport with simplistic moral binarism and our desire to save the world. I quote Peter Beinart, one of the only Iraq hawks whose apology piece was worth a damn. He writes of

a painful realization about the United States: We can't be the country those Iraqis wanted us to be. We lack the wisdom and the virtue to remake the world through preventive war. That's why a liberal international order, like a liberal domestic one, restrains the use of force — because it assumes that no nation is governed by angels, including our own. And it's why liberals must be anti-utopian, because the United States cannot be a benign power and a messianic one at the same time…. Some Iraqis might have been desperate enough to trust the United States with unconstrained power. But we shouldn't have trusted ourselves.

Nothing has changed, in this regard. When people are agitating for war, they imagine a frictionless universe in which intent determines outcome. But the law of unintended consequences rules, and even aside from the inevitable civilian casualties, the very real possibility that we could lose, and the potential for nuclear conflict, there are all manner of ways American intervention in Ukraine could go sideways. That is the unmistakable lesson of the past two decades of conflict for the United States - it can always get worse in ways you never foresaw.

Consider, for example, how Ukrainian residents loyal to Russia and Putin will be treated after Russia is beaten back, should that occur. (And yes, there are many people in the Ukraine who support the Russian state.) These people would face almost certain oppression and violence; this has been true of essentially every major sectarian conflict of the past century. Kosovo is beloved of a certain strain of liberal who thinks of it as the Good War, but as Adam Curtis reminded us a decade ago, in fact post-intervention Kosovo was rife with violent reprisals against the losing side. Are you comfortable owning the consequences of the immediate post-war period? The potential for score-settling, the likelihood of martial law, the consolidation of power by reactionary forces in Ukraine? When you break it, you buy, friends. If you’re going to own support for war you better be ready to own all of war’s worst consequences.

Let me leave you with this. Every time there’s a potential armed conflict for America to get into, there’s a layer of people who should know better who talk themselves into it. Often these are people whose politics are essentially animistic and Freudian, and as such they are vulnerable to accusations that opposition to war makes you unmanly or whatever. Some of them are just too idealistic to live and think that there’s such a thing as a Good War. Many are practicing disaster capitalism. All of them will settle on some terribly righteous set of reasons to support this war.

But let me assure all of you: those are not the reasons we would go to war. Those are the reasons you might want the United States to go to war. But that’s not why the wars are actually fought. People thought we were going to war to free Iraqis, depose a dictator, and stop future terrorist attacks on the United States. Instead, we invaded Iraq to reestablish imperial dominance, ensure access to cheap oil, and to punish some vaguely Middle Eastern-looking people after we were humiliated. It doesn’t matter how sincere the more idealistic war supporters were; the mandates of the war machine rule. And so with the reasons we would go to war “for Ukraine.” You might want us to go to war for self-determination - but if we put troops in Ukraine they will do what we want and not what Ukrainians want. You may want us to go to war for international norms and the rule of law - but every aggressive action we take makes a mockery of both. You might want us to go to war for human rights - but there will be terrible reprisals against the many, many people in Ukraine who are loyal to the Russian state. You go to war with the war machine you have, not the war machine you wish you had.

When Democrats start getting hepped up to go to war, like they did with Iraq, you can’t underestimate the power of wanting to appear tough. A lot of left-leaning people quietly resent having to repeatedly formally oppose wars and lick their chops at the opportunity to finally pull out their dick. (Will Noah Smith grab a rifle and fight? I'm guessing no!) I am not so moved. Looks like there’s another war on. I’m against it.

I'm unclear what exactly you're calling for the US to do differently than it is now (if anything). As far as I am aware, US policymakers have made it clear that a shooting war with Russia is not on the table. Our responses to the situation so far have been:

1) sending "lethal aid" (weapons) to Ukraine to help them defend themselves

2) a small increase in US forces situated in nearby NATO allies as an act of reassurance that we are not going to renege on our treaty obligations

3) threaten significant economic sanctions against Russia if they do choose to invade

I think there are reasonable objections you could register against any of these policies. Sending weapons to Ukraine risks making a foregone conclusion unnecessarily bloody and painful when a swift resolution would be better for all. Sending additional US forces may be unnecessary and discourage our allies from stepping up to defend themselves. And economic sanctions will land heaviest on Russian civilians who are not at fault, while serving to bind the Russian oligarchs ever more tightly to Putin's regime.

What you seem to be doing though is establishing a false equivalence between American adventurism in the developing world (which is bad imperialism) with American alliances with our peers in Europe (who are willing partners reliant on American support for their security).

I fully agree that getting into a war with Russia over Ukraine would be a terrible idea. But it doesn't seem to me like that option is being considered by anyone especially serious. Perhaps I'm just reading different sources, and there's more hawkishness out there than I realize. I'm sure there are plenty of people who are eager to get in there and fight, but it doesn't seem to me they hold any of the positions of power within our current administration.

Your last para pointed to the most important reason to avoid war. It is deeply immoral and destructive to your country over the long term to engage in wars from which your family, your friends, and your class are excused.