Pushing Everyone Into College was a Policy Response to Other Policy

none of it happened by mistake

It’s been kind of a trip watching the conversation about student loan forgiveness play out over the first two years of the Biden administration. So much of the broader meta-conversation touches on issues I explicitly examined in my book The Cult of Smart. I have thus far resisted the urge to say “read my book!” at every opportunity, as that would be pretty sad. But I do want to touch on this question of whether students knew what they were getting into and should therefore be on the hook for the debt no matter what. I would argue that young people were relentlessly told in their youths that education is the only path to prosperity, and I would further argue that a changing economy left them with few stable ways to secure a middle-class existence other than college. Indeed, the titular “cult of smart” in my book refers to precisely this dynamic, both the ways that our economy funneled more and more students into college and the attendant ideology that suggests that one’s worth is equal to their academic ability. We became obsessive about intelligence as the singular mark of human value in concert with a policy apparatus that pushed more and more people into higher education. But why did the policy apparatus act that way?

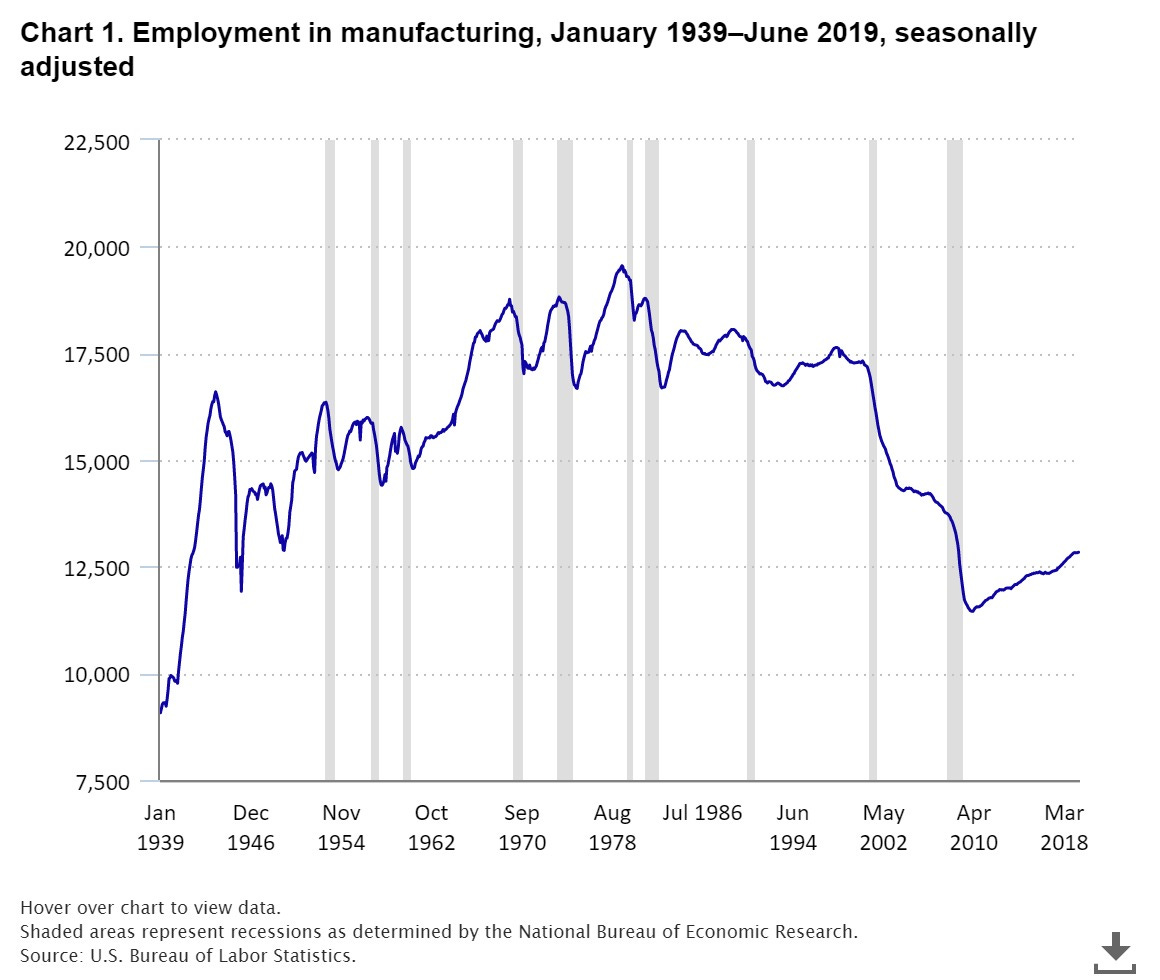

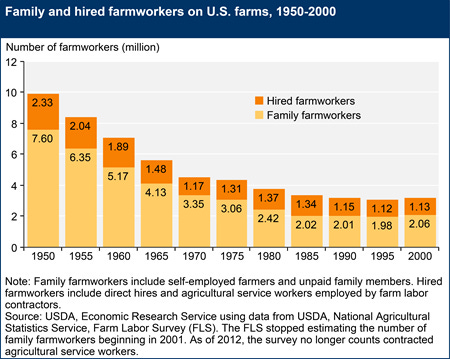

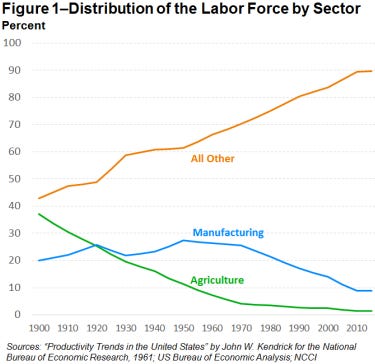

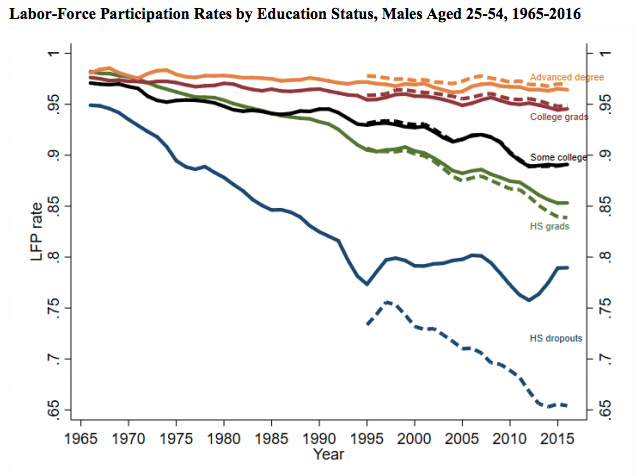

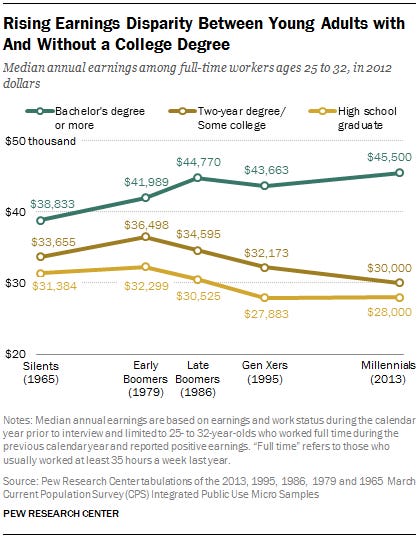

The relentless emphasis on college education grew in concert with the demise of the labor market for those without college degrees. Manufacturing, in particular, was a sector of the economy that enabled those without much formal education to earn solid middle-class incomes. And the decline in manufacturing employment that started around 1980 happened against a background of similar decline in agricultural employment that had been proceeding for decades.

The dynamic in these graphs is actually understated, as this all happened against a backdrop of population growth. Both graphs represent raw numbers rather than percentages of total workers. In 1979, when manufacturing jobs peaked, there were 100 million fewer Americans than there are now. By 1980, farming was no longer a site of mass employment; 30 years later, manufacturing had been similarly gutted as a source of employment. (Some 34 million American manufacturing workers left their jobs between 1993 and 2009.) Which meant that two industries that had traditionally been home to those without college degrees had seen their workforces shrink considerably.

One undeniable driver of the decline in manufacturing and agriculture jobs has been automation. We’ve simply become much better at using machines, which potentially have a high initial cost but have lower recurring costs than paying human beings. (If they didn’t, we wouldn’t bother to build them.) Says Henry J. Holzer of the Brookings Institution,

there are workers who lose out [from automation], particularly those directly displaced by the machines and those who must now compete with them… workers performing similar tasks, for whom the machines can substitute, are left worse off. In general, automation also shifts compensation from workers to business owners, who enjoy higher profits with less need for labor.

It’s common for defenders of automation (when not simply repeating the word “Luddite” over and over again) to say that automation creates jobs as well as destroys them. This may be true in aggregate, but when automation creates jobs it doesn’t usually create jobs for the same people. The net increase in jobs might not look so bad. The trouble is that the people who lose their jobs to automation are not the ones who will likely get the new jobs created by automation. A lifelong machinist with no degree is not likely to get a job servicing the complicated electronics of the new robotic machinery that has replaced him. Telling that person that the net impact on jobs of automation isn’t that bad is cold comfort. There have been a lot of attempts at retraining laid-off workers, but they tend to assume that job skills are entirely fungible, which….

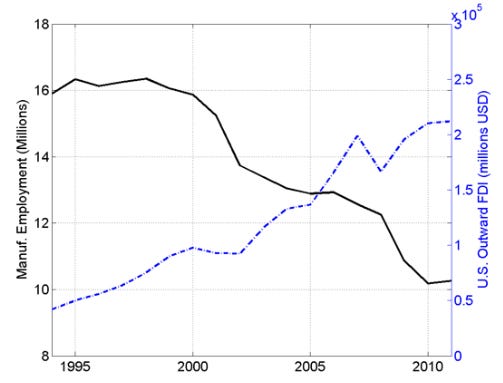

Another frequently-cited reason for the decline in jobs for workers without college degrees is offshoring. This contention is very controversial; globalization and the greater neoliberal turn have some vociferous defenders. The Clintonite, pro-NAFTA, pro-globalization tendency in progressive politics remains empowered in our discourse. Some from that school deny that globalization has led to serious job losses. But there has always been a counter-narrative that argues that globalization contributed significantly to the decline in American jobs for the uneducated. See, for example, this CEPR research which suggests that one-fifth to one-third of the decline in US manufacturing jobs can be attributed to offshoring and globalization.

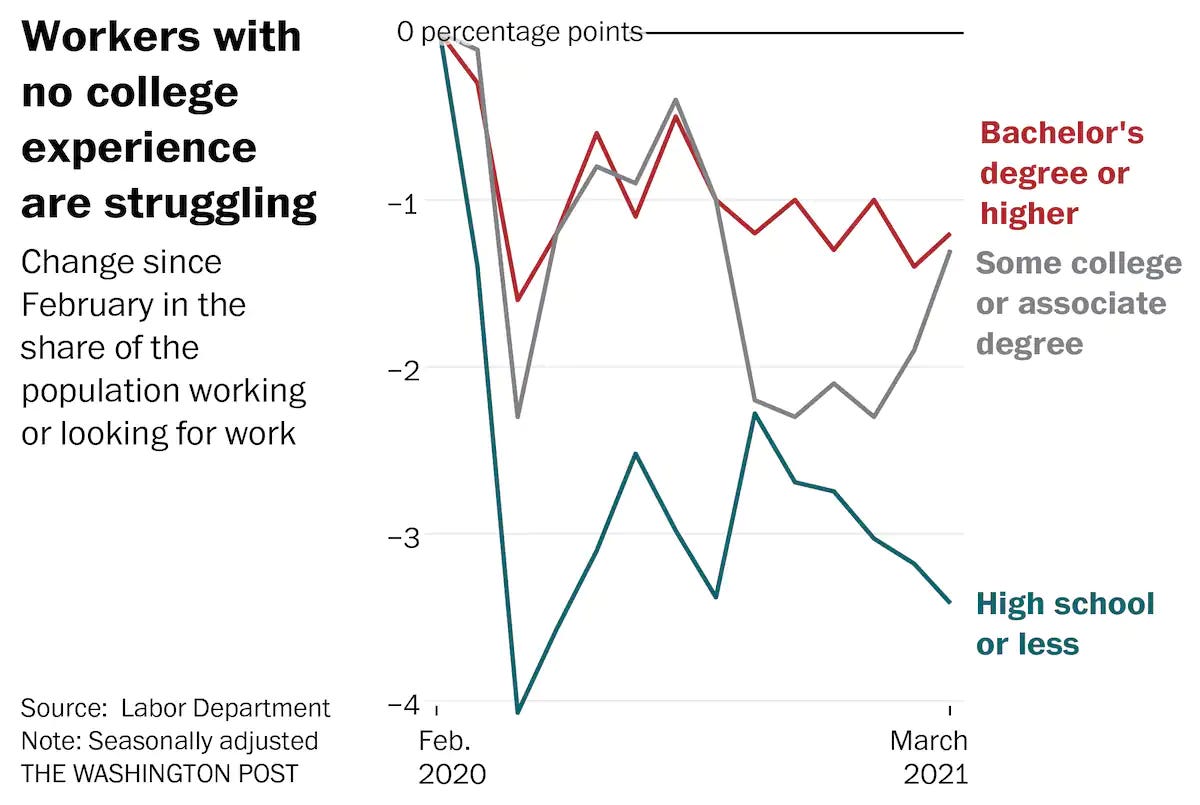

One way or another, people without college degrees have taken it on the chin for a long time.

This most recent economic recovery from the brief pandemic recession is a good microcosm of a decades-long reality.

In the span of 30 or 40 years, from the late 1970s on, a way of life more or less ended. The great American “factory at the edge of town” job was greatly diminished. Once upon a time there was a consistent way for people to get jobs without college degrees, or even without a high school diploma. Many of these jobs were unionized and allowed their workers to enjoy a middle-class existence, owning their own homes, having a car or two in the garage, and raising children. Because of tectonic forces beyond their control, these workers suddenly found themselves without a clear path forward.

I’ve suggested that it was the late 70s/early 80s when this dynamic began to take hold. The story I’d like to tell you today is that the relentless emphasis on college education as the driver of economic prosperity began at just about that same time. By the early Reagan administration, the impact of automation and offshoring was being felt in the job market. And in the early Regan administration, the crisis narrative of American education was born - a narrative that among other things suggested that all students should be college-ready, in order to access the kind of jobs that still enjoyed robust labor markets.

When I refer to the crisis narrative, I’m talking about the notion that American schooling writ large is in a state of crisis - the common assumption that American schools are of low quality, that our system is broken, and that we need to take extraordinary efforts to fix it. As I have pointed out countless times in the past, including in my book, this attitude is not defensible; the median American school, and the median American student, is doing fine. Our top 1% or 5% or 10% are competitive with those of any other country in the world. The problem is that we have a relatively small number of schools, clustered in particular geographical locations, that have such terrible outcomes that they drag all of our averages down. But the notion that our schools are generically bad has been conventional wisdom for most of my lifespan, reality notwithstanding, and nothing contributed to that perception more than A Nation at Risk.

The notion of an American educational crisis was certainly not born in 1983 with A Nation at Risk, a report of the Reagan administration that argued that Americans were falling behind in the classroom. (Falling behind the Russians, naturally.) But no individual text before or since did as much to orient the policy apparatus towards the notion that our educational system writ large was a disaster and in desperate need for reform, despite a great many critiques of its methodology and conclusions. Further, as I again found when researching my book, American presidents began pushing education as the key to economic opportunity around the start of the Reagan administration as well. Barack Obama said that a world-class education was the best anti-poverty program; his predecessor George W. Bush said “There’s no greater challenge than to make sure that every child… regardless of where they live, how they’re raised, the income level of their family, every child receive a first-class education in America”; Bill Clinton said during his presidency that “in the new economy, information, education, and motivation are everything”; his predecessor, George H.W. Bush, said that “Education is the key to opportunity. It’s a ticket out of poverty.” Education’s role as an economic driver is American political writ.

You might contrast this with the average American from 1960-1970, when America enjoyed perhaps its most egalitarian economy. During this period, the average student saw very little in the way of systematic data collection, which tends to serve as a decent proxy for the sense of ambient crisis in education. (The No Child Left Behind era was a pinnacle of both constant panic and relentless assessment in K-12 ed.) Not coincidentally, this was also a period of robust economic growth, low socioeconomic inequality, and a robust labor economy for those without degrees. What I’m arguing here today is that there’s a causal relationship between the decline of that labor economy - itself a consequence of deliberate economic policy - and the increasing insistence that college is the path to prosperity.

I worked in K-12 schools for several years, and was struck by two intertwined phenomena: the insistence that one’s outcomes were simplistically a product of their desire - that if you believe, you can achieve - and the belief that what young people should desire is to go to college. As I wrote in the introduction to The Cult of Smart, describing working in a school district in the late 2000s,

there was something odd about the culture of school, something disquieting. I was disturbed, for lack of a better term, by the ideology of the place, by the implicit set of beliefs that it shared with almost every school I’ve ever stepped into. In particular, I was struck by the relentless repetition of a single message: that every student was constrained in their lives only by their will, that if they worked hard and never gave up on their dreams, they could do and have anything. If they would only believe, the saying went, they would achieve. That effort and commitment were the sole requirements for success in life – not just to be healthy and happy, but to achieve one’s most outsized dreams – was the mantra, and it papered the walls.

I can’t tell you how many posters hung in this middle school that made this claim, each one expressing one cliché or another about the power of self-belief. I stopped counting after I hit two dozen expressions of that idea in the months I worked there. The message was in just about every classroom, almost without exception. I heard a similar message from a speaker at a school assembly, who asserted the preeminence of work ethic; from the coach of the cross country team, who told his charges that whether they thought they would win or thought they wouldn’t, they were right; and from a science teacher, who counseled his students that genius was a fiction and that to be a great scientist only took work and fortitude. Everyone involved in educating these young people was sure that those students who would succeed would be the ones who wanted it the most. I felt, at times, like I was living in a one-party state, where the official propaganda was repeated ad nauseum.

And the assumed end result of all this believing, all this trying, all this desire, was college. Even in that middle school, teachers and administrators talked about college as though it was the only noble path.

So deindustrialization is one facet of the story I’m telling, the educational crisis narrative is another, and the notion that college is the one noble path is another. Still another is the assumption that college’s purpose is straightforwardly to provide people with jobs. It was Ronald Reagan, more than anyone, who reformulated the purpose of college education away from liberal values or the training of an enlightened citizenry and towards job creation. The Chronicle of Higher Education’s Dan Barrett argued that, as governor of California and thus overseer of the University of California and California State systems, Reagan did more than anyone to make college a vocational enterprise first. “What I argue is that I see much more discussion in the public sphere about colleges needing to be job creation tools and less about developing abilities that might not have an immediate apparent payoff,” wrote Barrett. Reagan would then go on as president to use the crisis narrative to further define college as a jobs creator first. He presided over the neoliberalization of one of our country’s great university system, then over the decline of the uneducated labor market. No one in American history did more to create the current American condition, where students feel forced into a college pipeline that then saddles them with backbreaking amounts of student loan debt.

What I want to argue today is that the decline of the employment market for people who only had high school diplomas and the rise of the education crisis narrative are intertwined. I’m not an economist, but the evidence that offshoring and neoliberal economics contributed to job losses (in America and the United Kingdom) seems compelling to me. The Reagan-Thatcherite consensus on eliminating protectionist parties, dismantling regulation, and attacking unions led to a worsening labor market for those without college educations. Once you’ve made such a concerted assault on the Fordist model, with its unionized workforce and low socioeconomic inequality built on domestic manufacturing, you’ve got to have some other labor force model to sell to the public. Well, college-educated workers have traditionally enjoyed an employment and wage premium, and conveniently pushing for greater participation in college education could be done with egalitarian rhetoric. Drastic declines in per-pupil funding in public colleges could be papered over with easy access to federally-guaranteed loans - loans that would be, eventually, ineligible for discharge through the bankruptcy process. As a bonus, any failures with this model could be ascribed to public school teachers and their unions, which happen to be stalwart allies of the Democratic party.

When people ask how so many young people could be so reckless in taking on so much student loan debt, I wonder if they’ve spent any time in this culture in the past 40 years. For decades, we’ve insisted to young people that education is the key, that the way to get ahead professionally or personally is to go out and get a college degree. Our K-12 schools (public or private or charter) are absolutely steeped in this rhetoric; it’s all-encompassing. The young people who have followed the advice they were given for a decade and a half of formal schooling can hardly be blamed for following it. We might make more headway by asking what society-altering policies were made that pushed them in that direction.

Awful lot of people in here talking as if students are still taking "impractical" majors, but those majors (which are not to blame but that's a bigger discussion) have seen enrollment collapse for over a decade. You guys need to update your talking points.

For my boomer parents, they grew up in a world where a degree was a golden ticket. This they conveyed to me: the expectation was simply that I would go to university. To study what? didn't matter. Just graduate.

Of course, by the time my generation were graduating, it was no longer a ticket because so many people now have degrees. There's the basic market economics of something dropping in value as it is produced in surplus.

There's also the fact that just as factory jobs are diminished, a lot of white collar jobs have been removed too. The admin support jobs that used to make up many offices (secretarial pool, mail rooms, etc) have vanished. Executives type their own emails.

And the middle management jobs that once existed - many of them at the factories - have also gone.