Publishing is Designed to Make Most Authors Feel Like Losers Even While the Industry Makes Money

everything in modern culture is about status resentment

This week Kathleen Schmidt of Publishing Confidential, a newsletter to which I subscribe, took some swings at this piece by Elle Griffin, a post skewering the state of book publishing that was remarkably well-read by the standards of contemporary independent media. Schmidt is an insider with 25+ years in the industry, while Griffin is an outsider who has done well for herself by serializing two novels on her Substack. Neither makes one right or wrong, and both have important thoughts to share. But Griffin’s piece has achieved exit velocity and been shared by several people in big-deal media; for example, the piece was linked to in Ross Douthat’s NYT newsletter today. Here’s her summation:

The Big Five publishing houses spend most of their money on book advances for big celebrities like Britney Spears and franchise authors like James Patterson and this is the bulk of their business. They also sell a lot of Bibles, repeat best sellers like Lord of the Rings, and children’s books like The Very Hungry Caterpillar. These two market categories (celebrity books and repeat bestsellers from the backlist) make up the entirety of the publishing industry and even fund their vanity project: publishing all the rest of the books we think about when we think about book publishing (which make no money at all and typically sell less than 1,000 copies).

I’ll tell you upfront that I think that Schmidt has a better grasp of the facts, and I think Griffin’s stance, while emotionally understandable, is really an expression of a particular culture war rather than an honest survey of the industry. You may note that Griffin’s last sentence here self-contradicts; if there exists a “vanity project” of literary novels then celebrity books and the backlist cannot make up “the entirety of the publishing industry.” If you want to say that it’s just exaggeration for effect’s sake, I’m afraid you can’t do that, here, in this piece - if you’re throwing out numbers based on court testimony and professing to share the hidden secrets of an industry’s economics, you can’t allow yourself that kind of imprecision. And is it in fact true that all of the sales go to celebrities and the backlist? Of course not. Hanya Yanigahara’s A Little Life sold a million and a half copies, and it’s a relentlessly bleak literary novel by a woman who was plugged in but not famous. Yanigahara’s first novel The People in the Trees would probably slide comfortably into Griffin’s definition of the vanity project side of publishing, but her more ambitious - and not at first glance any more commercial - second novel sold insanely well. Of course, now that it’s been a few years, Griffin might be tempted to relegate A Little Life to the backlist, but that wouldn’t be very sensible. Every book on the backlist was once a new book, after all. If Griffin will concede that the backlist grows over time, that there are always new old books helping a publishing company’s bottom line, her claims don’t add quite add up. Somebody who isn’t a celebrity is selling books. Not many people, but enough.

The very fact that Griffin’s piece went so viral is a good reason you should be skeptical of it. A fairly dry discussion of publishing’s sales numbers seems unlikely to attract that kind of attention. But Griffin is no dummy, and I think she was very deliberately courting an audience that the online newsletter industry is absolutely stuffed with: people who carry around bitterness and resentment towards the traditional routes through which people achieve success in writing. Which might sound dismissive, but I don’t mean it to be. There are very many reasons to hold resentment towards the people who hold the cards in publishing, and I myself carry around a degree of that bitterness and resentment myself. As I’m still fairly new to publishing books, I don’t have a lot of angst about that world yet. But I’m 15 years into a career in media, and a lot of the frustrations, tensions, and bullshit are the same. There’s every chance for me to grow disenchanted by publishing the way others have. I know that I’ve enjoyed good fortune with books so far, despite tepid sales, and I know that I may not in the future. I understand the resentment.

Still. The trouble with writing towards that kind of resentment is that, while it’s a good way to juice subscriptions, it carries with it this inherent tendency to sacrifice what’s accurate in favor of what’s inflammatory. While Griffin never directly suggests that writing for big publishing houses has no advantages, many on social media have taken exactly that point. One of the top comments on Griffin’s piece, which reflects the overall reaction, reads

Your report confirms all that I have long suspected as agents and the big houses go. A very knowledgeable person told me recently that Hemingway and McCarthy would not get published today were they just starting out. IMO you waste valuable talent, time, and energy pursuing an agent and a big house. Worthless now.

Well, maybe Hemingway and McCarthy wouldn’t get published today, no. You can never be confident of that sort of thing, which is an indictment that applies to any of the creative industries. But I can only tell you that, personally, the advantages of having an agent and a publishing house are considerable.

I shopped my first novel (which I serialized here and may resurrect in some form someday) for over a year without success. I thought the process of selling a book was hopeless and opaque and hopelessly opaque. Then I got an agent, took meetings to try and sell my first book, and said “oh, dang,” because I saw how necessary good representation is in the industry. You can certainly say that this is all a part of the same problem, that agents are only necessary because publishing is broken. But in the world of publishing that we actually have, my agent has been invaluable. Meanwhile, the simple fact of the matter is that my first two books are better books because of all the resources I had available to me. Having other people to shape the project is an advantage that cannot be replicated any other way. The teams I’ve worked with have been filled with talented people. The editing was often annoying and occasionally wrong but always valuable. The work dedicated not to composing or editing but to producing and marketing the book was valuable. Getting set up with various podcasts and shows and book talks and events was valuable. Of course I understand that not everyone gets those affordances, and that that’s part of the anger. But when you’re specifically saying “this stuff has no value,” I just think that’s crazy. It certainly has had value for me.

The guy who bought my first book left St. Martin’s three months after he bought it, under what I understood to be acrimonious terms. The imprint was folded. (I think mine was the last book to appear with its logo.) This all should have been bad news for The Cult of Smart; I mean, it was bad news, any way you slice it. The book was an orphan before I had written any of it. And yet I never felt badly served by the publishing house. To their eternal credit, St. Martin’s put their entire back into that book. It didn’t sell great; as of last September it was at about 7500 copies moved, although I know the marketing push for the second book has helped move some copies since. Either way, I’m confident I got the best experience I could have expected under those circumstances.

Also, you know… there’s the money. The advance for my first book kept me alive when I was recently fired, broke, and hopeless in 2020. The advance for my second book bought the house I’m currently sitting in. This is life-altering stuff. Perhaps it’s unwise for me to express the value of advances that didn’t earn out, but had I been on a self-publishing model and sold exactly as many copies as I did, I don’t know how I would have made it in the 2017-2021 period. Again, I understand that this is privileged territory I’m occupying, but it’s privileged territory I’m in because I worked within those disdained traditional publishing structures. Some people make immense amounts of money in self-publishing, too, and they’re just giving a little cut to Amazon or whoever, not watching the agent take 15% and the publishing house take most of the rest. It’s all a series of tradeoffs and judgment calls. The point is that there actually are tradeoffs to be made, and it’s not at all clear to me that Griffin’s rundown works for everyone, even while I acknowledge that it’s working for her.

And, look - I was negotiating with Simon & Schuster over my next nonfiction book for four months, battling over tweaks to the proposal and to the slant of the project that I found to be rather ancillary, and that was unpaid labor that I found frustrating. Book promotion is a grind, though I can’t imagine any scenario in which it wouldn’t be. I am 0 for 2 when it comes to getting the title I wanted, and while the novel carries the name I chose I will not be surprised if I go 0 for 3 on nonfiction. (To be fair I don’t even know what I want the name to be for that book at present.) In general I think I’ve lost every argument that I’ve had with a publishing company, and I doubt that will change much over time. Which is fine -when you take people’s money, it’s no longer just your book, and there are key decisions (such as losing six pages of scientific detail in The Cult of Smart) that are going to be frustrating. Meanwhile you’ll recall that I said that nobody wanted to buy my first novel, and then I got my agent; funnily enough, he wasn’t interested in that book either, and I was in a state in my life when I could not have had less juice about such things, so I dropped it. If I chose to revamp the novel and try to self-publish it digitally, which I’ve thought about, I would have to at least check my contract and maybe fork over a portion of the proceeds to my agency, depending. There are complications and a loss of autonomy that come with all of this. But, for me? It’s all been worth it, easily, and I say that as someone whose first two books sold well enough to not be embarrassing but are still far from earning out their advances.

Forgive me for burying the lede to this degree, but - Griffin is not wrong that celebrity books (almost never actually written by the celebrities) sop up a distressing amount of book sales, that a huge portion of books don’t make a profit, or that in general publishing is a winner-take-all economy. But it is a mistake to suggest that this is a new phenomenon.

When I signed my first book deal, a friend who is himself a 20-year veteran of publishing sent me an email that included this sobering passage:

you have to understand, let’s say a Big Five house puts out 75 books in a year

typical year? - 50 don’t sell at all and are a clear financial loss; 15 sell enough to recoup the advance and maybe the overhead for all the work that went in; 5 are profitable but max out at modestly-to-moderately so; 5 are big hits that, along with all the ancillaries and back catalog, make the house’s nut for that year

Those are obviously loose and hypothetical numbers. But they match everything I’ve heard anecdotally, and jibe with Griffin’s figures from the trial. Again, though, I think that this has always been more or less the plan for publishing houses. It’s a boom-or-bust business on the individual book level but a fairly steady one on the macro level. Part of what’s weird about Griffin’s piece is that it represents some realities that will be unfortunate for individual authors, then uses them to suggest that they show that the industry is in trouble; she in fact predicts the imminent death of the big houses. But literally none of the specific observations that she makes suggest that the publishing houses have a broken model. She fixates on the inequality in publishing, the small number of authors whose books earn out, but doesn’t at all engage with the fact that this reality works for the industry if not the individual author. And in a piece that’s titled “No One Buys Books,” she leaves out any mention at all of book sales trends! Bonkers.

If you asked the publishing industry if they’d take the past five years of sales, with no context, they’d say absolutely. The pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 were great, 2022 was eh, 2023 was worse, who knows about 2024. This is all to say that there have been cyclical fluctuations common to any industry and no sign of the structural collapse that Griffin so clearly wants to find.

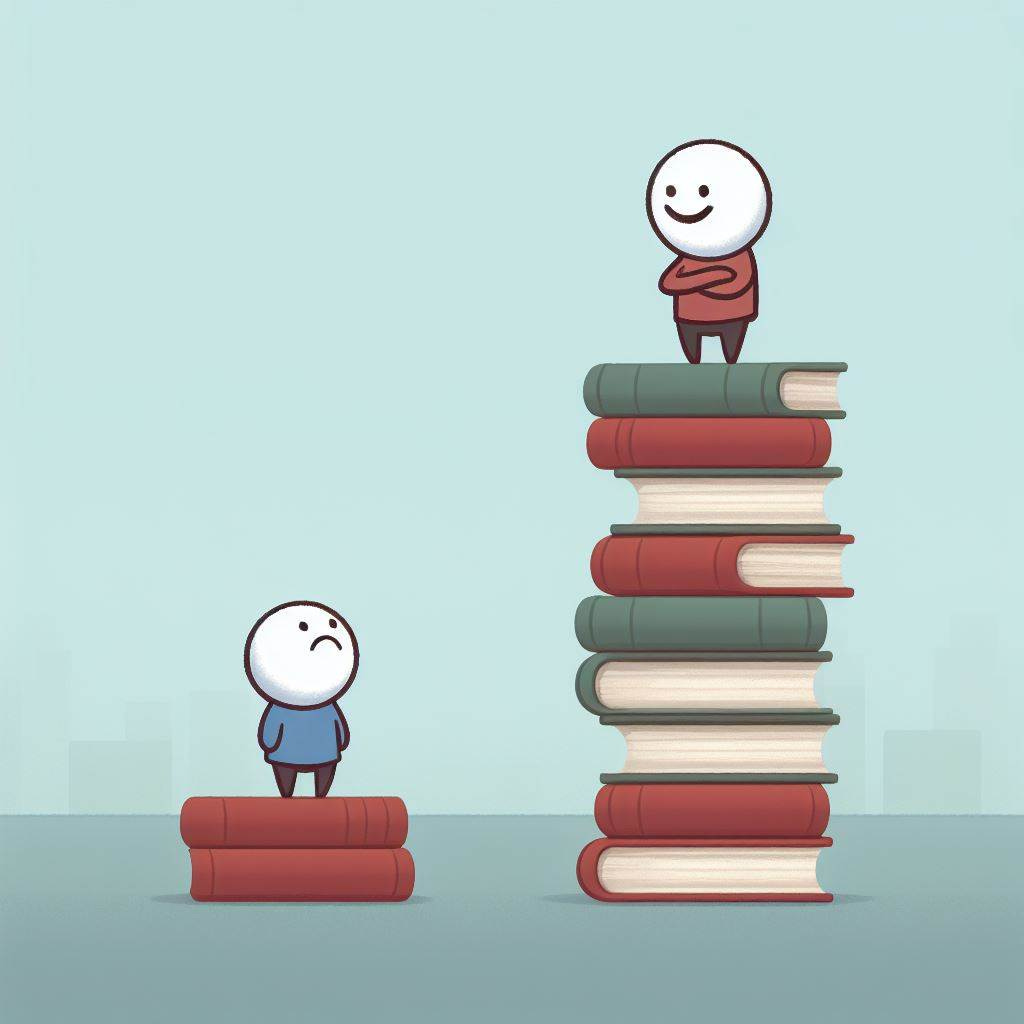

So as not to bury my headline here, it is certainly true that business as usual for the publishing houses leaves a majority of writers feeling life failures. That’s unfortunate, and even worse, I don’t think many literary agents prepare their clients for the reality that most books don’t sell. You sell a book and feel great, you go through the process because you’re inspired, you labor over the text, the money isn’t great when you do the math, and then it comes out, and there’s no big event; it just appears on bookstore shelves. “Pub day” is structurally anticlimactic unless you’re JK Rowling. If you’re lucky, there will be a round of reviews, and you’re left wondering what happened when your agent euphemistically tells you that the thing ain’t selling. And, again, structurally, by design!, there will always be more disappointed writers than happy writers.

So why isn’t this all an endorsement of Griffin’s point? Why isn’t it clear that self-publishing is the way to go? Because there’s no denominator in Griffin’s essay, none. That is to say, she is suggesting a comparison (traditional publishing houses vs self-publishing) when she has no numbers with which to make the comparison. There’s no big self-publishing merger that produced lots of public data to crunch. Against the hard numbers that make publishing look bad, she can only pitch broad waves to conditions in self-publishing. That’s because we simply don’t have the necessary information. But it is a certainty that self-publishing follows a Pareto distribution as well. There is no doubt that the vast majority of people trying to make it in self-publishing are failing. There is no doubt that the vast majority working on newsletters will not have the success Griffin has had. Success in creative fields is hard to come by no matter what the model. That’s always been true of the arts! There’s no halcyon days when most artists made a living, and every reason to believe that creators of all types face markets defined by immense inequality. This Pareto distribution seen in Patreon patrons, put together by Stephen Follows, is a stark statement, especially given that the Pareto effect is fractal:

Almost no one who tries to make it in the crowdfunded economy succeeds, whatever the medium or genre they work in. Just like most published books fail. Griffin and others who inveigh against the gatekeepers, for all of their good points, consistently mistake the gatekeepers as the source of all that failure. But the source of that failure is that the public has a finite appetite for media, tends to mostly like the same things, and has limited time to discover new artists. With self-publishing, we can indulge in survivorship bias by looking at various flourishing independent writers and saying “aha!,” but that’s not sensible. Meanwhile, the publishing houses are a convenient receptacle for anger, whereas even if writers are inclined to be angry about their lack of success in self-publishing, since there’s no central self-publishing entity, there’s no one to get mad at. None of that helps us with the only question that really matters here: for any individual writer, is self-publishing better than going with a traditional publishing house? For me, it’s a certainty that the answer would have been no. As I said, I did self-publish that first novel, serially, and even paid an illustrator who came up with gorgeous artwork for. The novel was attached to my main newsletter, which had a mailing list of 50,000. Even with that marketing advantage, the average view count for each of its fifteen chapters was about 2,000. I understand that the novel could just suck, but the point remains that self-publishing is no guarantee of anything even with a large built-in audience. Meanwhile, publishing house money has made a huge difference in my life.

This entire conversation is, of course, colored by various forms of status anxiety. Self publishing involves the usual complications of artforms practiced outside of traditional types of gatekeeping. Though I am a longstanding skeptic of liberatory narratives regarding the technology-assisted demise of gatekeepers - some gates are meant to be kept - I will say upfront that there are definitely major advantages to undermining the old system. Traditional systems through which people have advanced in artistic fields have failed to provide talent with opportunity, time and again. Surely there are all manner of painters and writers etc. over the course of history who had all the talent necessary to succeed but never got a chance because whoever the relevant gatekeepers were at the time didn’t recognize their potential. (We don’t know who because they never got the chance!) The traditional Hollywood system seems absolutely intent on demonstrating the worst elements of gatekeeping in the creative arts, falling deeper and deeper into shameless nepotism. It is indeed true that traditional publishing, like the music business and Hollywood and journalism, has done a lot over the decades to deepen historical inequalities of sex and race and class.

And they just get it wrong, all the time, even when doing their best. My godfather is one of the smartest guys (and best novelists) I know, but when he worked at the bottom level at G.P. Putnam he was the one who pulled Watership Down off of the slush pile and rejected it, sure that his bosses would get angry if he passed along a book about rabbits. It has gone on to sell more than 50 million copies. That sort of thing is inevitable. (Sorry Flip!)

Writing is also an intensely personal endeavor, and so rejection by the various apparatchiks who decide who’s in and who’s out can feel especially cruel. Of course, rejection by the audience is cruel whether you publish with a house or self-publish; there is, however, the fact that when you do it the traditional way, you’re disappointing more people than just yourself. (I really encourage book writers to absorb what a large percentage of books don’t sell, and similarly encourage agents to make that clear too.) As in any creative field, the monetization of writing is always far easier if you write particular kinds of things in particular kinds of ways for particular kinds of audiences and in particular genres. The new frightens those who make those decisions because the new does not have a track record. And there are all sorts of exploitative and unfortunate dynamics in publishing specifically and creative industry gatekeepers generally.

But… none of that proves what Griffin is trying to prove. She’s championing a different model but presents no data that suggests that writers are more likely to succeed according to that model. If you think that it’s lonely and sad to put out a book that nobody buys, I invite you to search around for the thousands of blogs and newsletters and self-published novels out there, some of them written by very talented people, that have gone nowhere either. I actually think it can be crueler when you’re doing it on your own, as many people have found themselves in a place where their writing is not remotely able to pay their bills but still commands more and more of their attention, and they’re stuck in a perpetual state of not knowing if they’re a happy amateur or a disgruntled professional, if they should give up or keep going. Substack has championed writing and writers, for which I’m very grateful, but of course it’s a financial necessity for them to oversell the amount of opportunity out there on their platform. Here’s the reality: there’s always been far more entrants into creative fields than those industries can bear in terms of providing people with a living, and the digital tools that have torn down barriers to entry have simply increased the competition and made the overall Pareto distribution even more brutal. That’s not gonna change, no matter how many of the gatekeeping industries go down. You can’t have a society where no one feels fulfilled unless they’re an actor or a musician or a novelist, but that appears to be the exact culture we’re building, and it’s tough.

I am, however, very happy to live in a society in which self-publishing is possible, and I am myself obviously a product of the independent publishing tools the internet has afforded. Nobody was ever going to give me a staff job.

Griffin’s post is not without merit, and obviously it’s been compelling for many people. The problem is that it’s an argument about values masquerading as an argument about facts. Like absolutely everything else in 2024, it’s a little slice of culture war. Seeing yourself in terms of a binary divide can help with the loneliness and aimlessness of a lonely and aimless industry. I’m certain that many of the people who have made the piece go viral have never gotten a fair chance in publishing a book the traditional way, and also that some are those who have published books, seen them fail, and nurtured the wound. (Many of those people are in media, which helps explain the visibility of this animosity.) I have sympathy for them all. It’s a brutal business, selling words. But people still buy books. People still read them. People will go on writing and buying and reading books. Though the Big Five might collapse and the terms of the game might change, there will still be big corporations picking winners, putting together books, and acting as gatekeepers.

My own books haven’t really sold, and with a couple coming out in the next two years, I could find myself unable to sell one in the near future. But I will write them while I can, if only because of the odd chance that someone might discover a book I wrote years after it came and went, and in that way connect with me, another version of me. As a young reader I was always delighted to find a book in the library that had not been checked out in 10 or 15 or 20 years, which was an affordance of the paper era of library recordkeeping. I would then dive into it and disappear into the ideas and arguments of someone who never could have counted on me as a reader when they set out to write it. This blog will be deleted when I’m through with it, and I will click the button lustily when I do. A physical book of mine might by some crooked accident find its way into the hands of a reader in 2124, and even if it’s just one person, that one time, that’s more than I could have once hoped for. It’s not much, but there are few things for human beings to hang a life on, when you think about it.

And if you write and struggle, I have great sympathy. The path of success is fickle and strewn with random chance. The cream doesn’t always rise. There is always a chance you’ve been denied success because of unfair bullshit. You do, however, have to consider the possibility that the problem is you.

Everything in modern (tech) culture is designed to make the tech innovator rich and pay the people actually producing something as little as possible. Just like the Rockefellers of old....

Books continue to sell in the aggregate. Any individual writer's chances of selling more than 20,000 copies are extremely low. Many of our most celebrated writers—the ones with their books displayed on the front tables—don't sell more than 20,000 copies. Selling more than 10,000 copies of a book, with a commensurate advance, is an unqualified success.