Psychosis is Not the Absence of Consciousness

This is the first post in (the first annual?) Mental Illness Week at freddiedeboer.substack.com. That’s Mental Illness Week, not Mental Health Week. Mental health is an idea, a vague and unhelpful one. Mental illness is a reality.

n of 1 on this one, guys. But it’s my true experience.

In our general cultural conversation, and particularly in pop culture portrayals, psychosis is frequently assumed to entail a lack of consciousness. The psychotic patient is not aware of themselves or their actions. They can’t control their actions because they aren’t even aware of what’s happening; their mind, their self, has been hijacked by some animal force that operates independently of themselves, with “themselves” understood here to be their consciousness. We exempt those suffering from psychosis from legal and moral consequences for their actions, when convenient for us, under the presumption that they were not in control of those actions - indeed, under the presumption that they were not “they” at all. When psychotic, they were somebody else, or no one at all.

This conception of psychosis has no connection at all to my experience of living with a cyclical and recurring psychotic disorder.

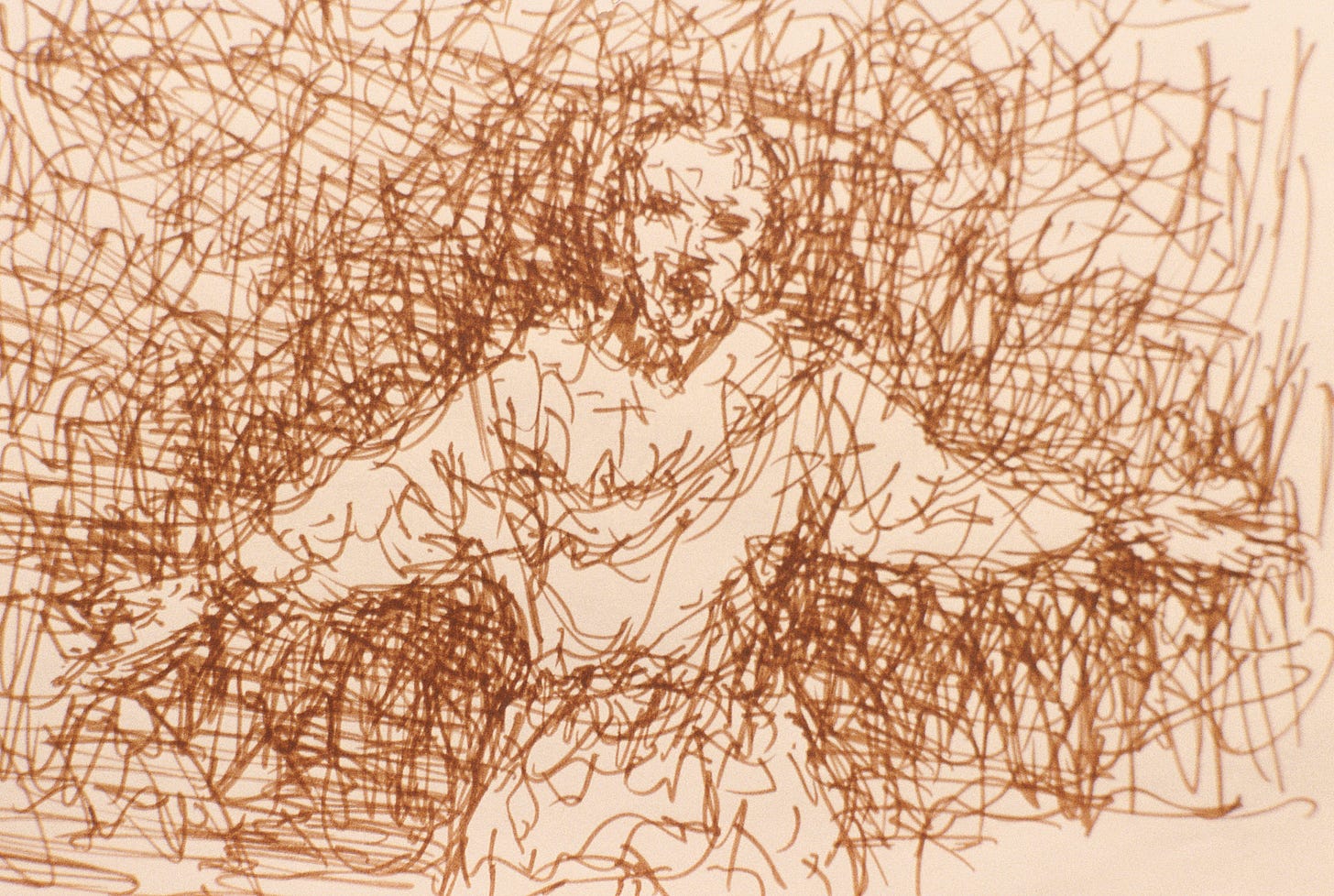

For me, the experience of psychosis is too much consciousness, if that’s not too cute. That is to say, yes, I experience intense emotions I can’t control and through some dark process my conscious mind develops irrational beliefs - not fantastical beliefs, like I can fly, but irrational beliefs, like an ex-girlfriend is hacking my bank account, unhealthy thoughts, unjustifiable urges. But those are interpreted by my consciousness. My consciousness has not diminished. I have not ceased to be there. Indeed, I cannot escape “I.” I am everywhere. Under normal conditions, the I must come into contact with reality, with evidence, but when psychotic my I feels the buffeting waves of terror and paranoia and, searching for stable moorings, finds only its own horrified self. It’s like crawling through a dark hallway towards a dim distant light and, when you finally reach it, you discover it lights only the grim tight confines of where you were when you began.

I know that this is likely hard to understand. I assure you that it’s hard for me to understand, too. But for me, being psychotic does not entail the erasure of my conscious mind. Being psychotic means being trapped in the mind as the brain drowns it in a bathtub of terror and obsession. It would be so much easier if psychosis erased the mind. What psychosis actually does is to force you to see what a thin reed your conscious mind really is, how totally defenseless it is before the animal power of your primal brain, should you be unfortunate enough to ever be exposed to that encounter. To be psychotic is to occupy your consciousness, to be aware, and to realize that doing so makes no difference in face of the raw violence of the disordered brain.

Why does it matter? Is this anything other than an academic question? It is. First, it’s profoundly relevant to the question of how we treat people suffering from psychosis, particularly legally. Look at a case like that of Aurora shooter James Holmes, a man who could hardly be more quintessentially schizophrenic and yet whose diagnosis was repeatedly doubted during his trials. He purchased weapons, ammunition, and a combat vest before the massacre, after all, and he had detailed (in the bizarre manner of a deeply mentally ill man) his plans in a notebook. For many people, this clear premeditation meant that he was sufficiently aware to be deserving of the full force of society’s justice, and to some among them this meant that he should die. But the assertion of premeditation and thus consciousness is a non sequitur. That Holmes was not operating totally without consciousness does not mean that he was capable of normally processing information or making decisions under ordinary conditions. The assumption that psychosis precludes consciousness is a deep misunderstanding of the condition.

For the record, had he been found not guilty by reason of mental illness, James Holmes would still never have walked free again.

You cannot look at premeditation as proof that someone is not psychotic. To experience paranoid psychosis is to be drenched in premeditation; it’s to be unable to turn off your brain’s capacity to premeditate. Psychosis is a form of overthinking, a form that kills. Paranoid schizophrenics are often the most meticulous planners. I think again of the apocryphal story of an asylum where there was a fire, and the exits appeared blocked, and the sane and rational staff panicked in fear of death, but the psychotic patients calmly led them through an intricate path to safety that only they knew. Because paranoid psychosis is not only not inimical to planning, I would wager it’s an addiction to planning.

Every time there’s a mass shooting, social media explodes with my least favorite phrase: “mental illness doesn’t do that.” There is, in the liberal imagination, the notion that the mentally ill should be considered totally and perpetually blameless; this is the laurel that they want to give to all “marginalized identities,” the poisoned chalice of blamelessness, the status of permanent and preemptive acquittal, like you give to a child, or to a clumsy but friendly animal. This is no gift and no way to respect, to honor, or to help, but today’s progressives know no other way, cannot conceive of sympathy that attends judgment, of the mercy that should be shown to the guilty. They can extend compassion only to those whose souls are spotless. Thus “mental illness doesn’t do that,” any time there’s a mass shooting, when they would like to press for gun control or demand that the real culprit is white supremacy. At the heart of it is a conception of psychosis, of mental illness, that isn’t a conception at all. It’s only a convenience. And in the end all our culture knows to say is “get some help.”

Why am I writing about mental illness this week? The truth is that for a couple of months I have been struggling, struggling with my disorder and the tools used to manage it. This is part of the process of management, a term I like more than “treatment” and much, more more than “recovery.” Sometimes you struggle, and I have been. Not for any reason. Not due to any life events. But because in my brain lives an animal, one that spends most of the year in hibernation or torpor, and periodically it wakes up and stomps around the house, demanding attention and worry as tribute. I hear the dim flutes of mania off in the distance. My skin buzzes like an old fluorescent tube, I grind my teeth day and night, I can’t sleep without a slug of benzos or of trazodone. I feel tectonic forces inside of me even as my body groans against the weight of immense doses of emotion-obliterating drugs.

People like mental illness narratives, these days. But they only want to take the mentally ill in two forms: in the full, florid madnesses of their imaginations, cinematic and satisfying, or in a state of wise and frictionless “recovery,” looking back at it all with the equanimity and grace of those who have suffered and know they will never suffer again. The grubby, boring, recursive reality of chronic mental illness, the uphill scrambling for temporary and uncertain gain, does not provide the necessary dramatic satisfaction of legibility.

I’m medicated and I will be OK. I keep comments off on this post not because I fear having to argue with people but because I could not stand to confront the well-wishes that would inevitably come. I’ll survive. I just can’t pretend this is all something that happened to me, instead of something that is happening to me.