Paywalls or Constant Intrusive Ads: Pick One

money has to come from somewhere, or interesting and challenging writing dies

Last week I published a piece for Compact. Its headline reads “The Left’s Vapid Anti-Musk Discourse.” This invited a lot of criticism; how dare I defend Elon Musk! This, I’m sorry to say, was a weird criticism. It was weird because the essay is explicitly and unmistakably anti-Musk. Here’s a key passage.

My point isn’t that Musk should be immune to criticism—it’s that the millionaire and billionaire class that collectively owned Twitter prior to Musk’s takeover deserves just as much, and for structural reasons. The fundamental problem with Elon Musk lies in his structural class position, in his status as a member of the bourgeoisie. His position in the class structure compels Musk to wield his immense wealth to reproduce that structure. He would do the same even if he spent all his time singing the Internationale and kissing puppies.

The point, in other words, is that Twitter used to be owned by someone from a particular economic class, and should Musk get tired of his new toy he’ll sell it to people from that same class. What I’m complaining about in the essay is not that Musk is being criticized but rather that the criticism leaves off the hook the rest of the ownership class that previously owned Twitter, such as the Saudis. (That is, an autocratic theocracy that beheads people for being gay.) The basic contention of the essay is that Marxist class analysis teaches us that the ownership class as a class is our enemy, and that moralizing about individual members of that ownership class is not a Marxist project. That he is the world’s wealthiest person does little to distinguish himself from the rest of the ownership class, and nothing to change the basic class analysis; he’s no better but not particularly any worse. The argument was never that Musk was good. The argument was that grownup left analysis (and specifically Marx) teaches us never to believe that there is such a thing as a good capitalist. They oppress by their class nature, not by their individual choices, and particularly not because they annoy you on Twitter.

Of course, the basic issue is that the critics misrepresented my piece because they didn’t read it before they criticized it. This is an absolutely mundane element of being a writer online, and I’m inured to it after 15 years of doing this. For the record, there’s no defense for critiquing things you haven’t read, no matter what the scenario. It’s a behavior that’s become more and more tacitly approved by the crowd over time, and it sucks. There is, however, a complication that some would point to: Compact has a paywall. People couldn’t read the whole argument because they haven’t subscribed to Compact. It should go without saying that this is not really a defense - if you can’t read it, just don’t comment on it! (Even worse, even if you aren’t a Compact subscriber the last visible paragraph of the preview makes what I’m going to argue pretty clear.) And I also want to say, if you’re annoyed that you can’t get past a paywall - tough. Because an era of rising paywalls is absolutely necessary if you want writing to survive as a profession, and if you want good journalism and analysis to endure.

For years and years, I swam against the current when it came to this subject. There was a deep bias, within the media industry itself, against the notion that anything should be paywalled in media and writing for a long time. You could take a look at TimesSelect, an early, failed attempt by The New York Times to directly monetize their online business as their newsprint business collapsed. People in the business mercilessly mocked the NYT for their efforts. It became one of those deeply annoying memes that proliferate in the broader media/journalism/commentary, the kind that becomes a marker for people to demonstrate in-group status within the profession. Nobody remembers, but I remember. And I remember what I said then and believe now: trading writing for money is a business plan. Giving writing away for nothing is not. I said this over and over and caught hell for it, and I’m perfectly happy to take credit now that so many big players throw up paywalls. Ads are the alternative. Well, the simple reality is that the online advertising business is brutally competitive, it’s controlled not by individual publishers but by a handful of giant firms that suck up the vast majority of funds, and ultimately it cannot serve as the sole funding source for journalism and commentary to survive. People didn’t put up paywalls because they wanted to; they put up paywalls because they had to. And I would argue that the result is a more varied and free world of written commentary.

If you look at the Times now, you’ll see that they’re enjoying more financial stability than they have in decades, thanks to their decision to go hard on paywalling their content and charging for digital subscriptions. Because, again, trading a product for money is a business plan; giving a product away for free is not a business plan. Moving a lot of those subscriptions, particularly during the Trump era, has allowed the NYT to go on an unprecedented hiring spree and produce a similarly unprecedented amount of content. Whether the dominance of the Times in hiring up so much talent is healthy for the industry is a fair question; whether other publications can hope to replicate their model is another fair question. But not that long ago the company was in genuinely severe financial distress and facing pressures to cut essential journalistic services. Now they’re flourishing - because they’re forcing people to pay for the product they produce, no more complicated than any other business trading product for cash.

(For the record, I know that if someone wants to beat a paywall badly enough, they’ll find a way to do it. I’m not naive. The hope is that some combination of inconvenience and shame will compel people to support writing financially.)

And publications that churn out a lot of valuable stuff deserve to get paid. Look, for another example, at ESPN.com and ESPN Insider. I’m frequently annoyed with ESPN the company. But the amount of value ESPN.com adds for the average sports fan is insane. You have the breaking sports news, aggregated in one place and updated near-instantaneously. You have their GameCast system which lets you follow along with a game as closely as you can without actually watching it. You have box scores that provide a whole host of stats, traditional and advanced, again calculated and posted near-instantaneously as games progress. You have analysis and opinion about sports-related stories. You have betting lines and betting advice. (I’m sure direct integration with an online sportsbook is coming.) You have 100% free fantasy sports leagues that are highly sophisticated and among the best in class online. You have extensive video highlights of every major sports event. All for free. And so many millions of people check the site habitually throughout their day.

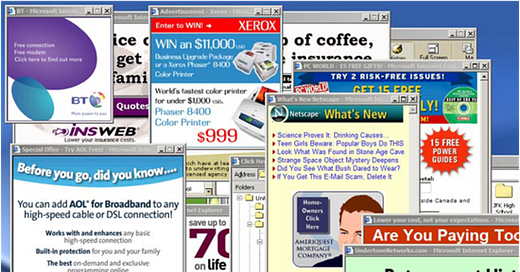

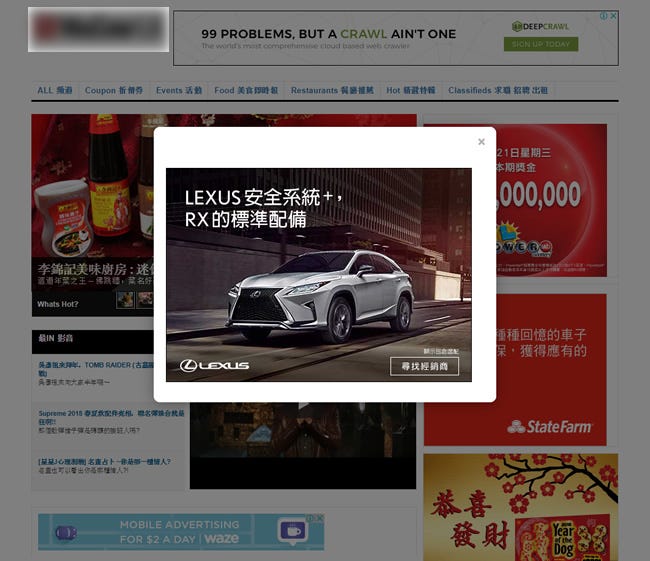

So when I hear people complain that some of ESPN.com’s content is paywalled with the ESPN Insider system, I really do get annoyed. You’re getting so much content for free! They’re asking you to throw down a few dollars a month to get more. If you don’t want to do that, don’t do it. Live without the content. And if you insist on making the anti-paywall attitude into a holy war, you’re just subsidizing this experience:

And, look, I get it - I get annoyed too sometimes when I want to read a specific piece from a site that I don’t want to pay for in general. But the only alternative to paywalls is advertising. And if you want sites you read to look not that different from the ones above, I guess you can go to war for an all-advertising model. You have that right. But as the revenues of online advertising continue to plummet, and structural problems with the model play out, the ads must become more intrusive and more inescapable. You’re all aware of the extreme lengths advertisers and publishers will go to in order to capture your attention. I’m happy to pay a select number of publications for the right to read if doing so cuts down on the number of intrusive ads I have to endure. If I don’t want to read something that badly I won’t pay for it, just like I don’t purchase a lot of things I look at and want on Amazon. That’s just a basic adult choice.

I know, you’ve got an adblocker. And also you don’t want to pay to get through a paywall. I hope you at least understand that you’re contributing to more, and more intrusive, product placement in the media you watch.

This post is not an advertisement for Substack, and indeed there are a lot of writers who have in recent years found ways to monetize their writing with competing services too. Substack or not, I really think this new era of subscription newsletters is a great thing. Most of the people who write them aren’t making their primary living by writing, but many are earning enough to make a real difference in their lives. I thank those of you who have helped pay for this project and thus my life, and I encourage those of you who are inclined to and who have the means to fund writing that has brought value to your life.

The early days of the internet are often fondly remembered as a halcyon age. (In my experience, the good old days of the internet for any given person are defined as whenever that person started going online, before all of these boring normies showed up.) I don’t know if I was ever part of the golden era of the Internet; in my earliest days I used a service called the Sierra Network that let me play a game called Boogers against strangers, but other than that I wasn’t much of an internet user until after everyone else was getting online with AOL. Many avid and older users of the internet want to replicate the freedom, openness, anonymity, and sense of possibility the early internet promised. And there were indeed virtues to those olden days.

But the internet as a mass phenomenon is now several generations old, the technologies have largely matured, and a host of powerful entities have taken control of almost every corner of online space. Refusing to pay for anything won’t bring the good old days back. We can have a broad variety of perspectives and a tremendous amount of information that’s expressed in written form, or we can not have it; we can drown it in advertising, or we can at least limit the advertising that hangs around the stuff we’re interested in. I know that not everyone has the financial means to contribute, and I also know that many of the people reading this are already doing their part. What I would like to say today to those that hate both online ads and paywalls is this: pick one.

As my username suggests, I am on team pay wall. However, that comes with its own risks. The NYT, or at least most desks within the NYT, is terrified of offending its own readers. The threat of an audience revolt is real, and this prevents real reporting from taking place, because it's natural for people - all of us, not just NYT readers - to prefer lies that confirm our biases to truths that are uncomfortable. Advertisers care about 'brand safety', of course, but they don't really care about reader comfort, as long as people keep reading.

One of the reasons I like this blog is that Freddie clearly doesn't pander to his readers and makes it clear that if people are so offended or in disagreement that they want to unsubscirbe, they are more than welcome to do so. There are other publications that don't do this, and that bend in the wind, just as they would if an advertiser told them to spoke a story. Ultimately, then, the danger of both approaches can only be resolved at the level of management and ethos.

I agree completely with the basic point: services for money. I do want to add that it would be great to have a third alternative to advertising and subscription models. It would be great if there was an option for buying individual articles. Occasionally a random internet deep dive will take me to something like a 1985 interview in the Bloomington Gazette. Obviously, I do not want a subscription to the Bloomington Gazette. But I would be happy to pay 10 or 25 cents to read the article. If it is feasible to implement such an option, it would be quite profitable. You would be able to sell to occasional readers, but regular readers would still prefer the price of a subscription.