No, Francis Fukuyama is Wrong, Not Just Not Even Wrong

the sweep of history will not look kindly on 20th-century chauvinism

If you’ve had “Freddie defends Michael Hobbes” on your bingo card for awhile, well, today’s your day.

In the above linked piece, Ned Resnikoff critiques a recent podcast by Hobbes and defends Francis Fukuyama’s concept of “the end of history.” In another case of strange bedfellows, the liberal Resnikoff echoes conservative Richard Hanania in his defense of Fukuyama - echoes not merely in the fact that he defends Fukuyama too, but in many of the specific terms and arguments of Hanania’s defense. And both make the same essential mistake, failing to understand the merciless advance of history and how it ceaselessly grinds up humanity’s feeble attempts at macrohistoric understanding. And, yes, to answer Resnikoff’s complaint, I’ve read the book, though it’s been a long time.

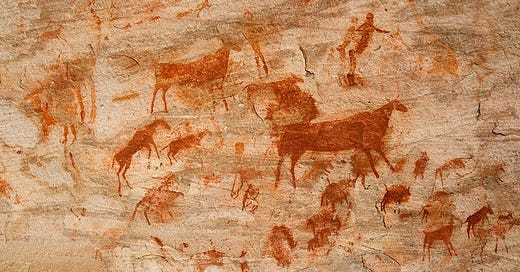

The big problem with The End of History and the Last Man is that history is long, and changes to the human condition are so extreme that the terms we come up with to define that condition are inevitably too contextual and limited to survive the passage of time. We’re forever foolishly deciding that our current condition is the way things will always be. For 300,000 years human beings existed as hunter-gatherers, a vastly longer period of time than we’ve had agriculture and civilization. Indeed, if aliens were to take stock of the basic truth of the human condition, they would likely define us as much by that hunter-gatherer past as our technological present; after all, that was our reality for far longer. Either way - those hunter-gatherers would have assumed that their system wasn’t going to change, couldn’t comprehend it changing, didn’t see it as a system at all, and for 3000 centuries, they would have been right. But things changed.

And for thousands of years, people living at the height of human civilization thought that there was no such thing as an economy without slavery; it’s not just that they had a moral defense of slavery, it’s that they literally could not conceive of the daily functioning of society without slavery. But things changed. For most humans for most of modern history, the idea of dynastic rule and hereditary aristocracy was so intrinsic and universal that few could imagine an alternative. But things changed. And for hundreds of years, people living under feudalism could not conceive of an economy that was not fundamentally based on the division between lord and serf, and in fact typically talked about that arrangement as being literally ordained by God. But things changed. For most of human history, almost no one questioned the inherent and unalterable second-class status of women. Civilization is maybe 12,000 years old; while there’s proto-feminist ideas to be found throughout history, the first wave of organized feminism is generally defined as only a couple hundred years old. It took so long because most saw the subordination of women as a reflection of inherent biological reality. But women lead countries now. You see, things change.

And what Fukuyama and Resnikoff and Hanania etc are telling you is that they’re so wise that they know that “but then things changed” can never happen again. Not at the level of the abstract social system. They have pierced the veil and see a real permanence where humans of the past only ever saw a false one. I find this… unlikely. Resnikoff writes “Maybe you think post-liberalism is coming; it just has yet to be born. I guess that’s possible.” Possible? The entire sweep of human experience tells us that change isn’t just possible, it’s inevitable; not just change at the level of details, but changes to the basic fabric of the system.

The fact of the matter is that, at some point in the future, human life will be so different from what it’s like now, terms like liberal democracy will have no meaning. In 200 years, human beings might be fitted with cybernetic implants in utero by robots and jacked into a virtual reality that we live in permanently, while artificial intelligence takes care of managing the material world. In that virtual reality we experience only a variety of pleasures that are produced through direct stimulation of the nervous system. There is no interaction with other human beings as traditionally conceived. What sense would the term “liberal democracy” even make under those conditions? There are scientifically-plausible futures that completely undermine our basic sense of what it means to operate as human beings. Is one of those worlds going to emerge? I don’t know! But then, Fukuyama doesn’t know either, and yet one of us is making claims of immense certainty about the future of humanity. And for the record, after the future that we can’t imagine comes an even more distant future we can’t conceive of.

People tend to say, but the future you describe is so fanciful, so far off. To which I say, first, human technological change over the last two hundred years dwarfs that of the previous two thousand, so maybe it's not so far off, and second, this is what you invite when you discuss the teleological endpoint of human progress! You started the conversation! If you define your project as concerning the final evolution of human social systems, you necessarily include the far future and its immense possibilities. Resnikoff says, “the label ‘post-liberalism’ is something of an intellectual IOU” and offers similar complaints that no one’s yet defined what a post-liberal order would look like. But from the standpoint of history, this is a strange criticism. An 11th-century Andalusian shepherd had no conception of liberal democracy, and yet here we are in the 21st century, talking about liberal democracy as “the object of history.” How could his limited understanding of the future constrain the enormous breadth of human possibility? How could ours? To buy “the end of history,” you have to believe that we are now at a place where we can accurately predict the future where millennia of human thinkers could not. And it’s hard to see that as anything other than a kind of chauvinism, arrogance.

Fukuyama and “the end of history” are contingent products of a moment, blips in history, just like me. That’s all any of us gets to be, blips. The challenge is to have humility enough to recognize ourselves as blips. The alternative is acts of historical chauvinism like The End of History.

About that “object of history.” Resnikoff advances the most common defense of Fukuyama, that critics are reading the term “end of history” wrong - he doesn’t mean “end” as in ending, he means “end” as in purpose. “He’s not talking about its chronological end; he’s using ‘end’ here to mean something more like a motivating force,” writes Resnikoff. As I said, this is a common rejoinder, but I find it quite confused. That motivating force is still a vector and a goal, a direction that implies a destination. Indeed, in other parts of the essay, Resnikoff is plainly talking about liberal democracy as an endpoint of human social evolution. In Resnikoff’s defense, Fukuyama does that too; he’s been coy about this definitional slippage for several decades now, stepping from one foot to another when discussing the end of history as fits the moment. Fukuyama’s defenders often act as though he’s this humble intellectual who put out a modest argument and was suddenly waylaid by bad-faith critics. In fact, Fukuyama went on a multi-year publicity tour about this idea, dined out on it, sold a lot of books based on it. And throughout it all, he’s taken advantage of this play on words to both provoke (saying history has ended is a very provocative idea) and to defend himself (hey, I was never actually saying history has ended!). In general, there’s a slipperiness to the whole concept that allows it to evade criticism.

Resnikoff address this.

Okay, you might say, so maybe Fukuyama’s not wrong exactly. But that’s only because he’s not making any provably true or false claims. All of this high-minded bloviating about the arc of history is completely unfalsifiable. On the one hand it’s not wrong; on the other hand, it’s not even wrong.

To which I say: Look, either you think philosophizing is a socially useful human endeavor or you don’t. I for one don’t subscribe to the vulgar positivism that says all propositions are either empirically falsifiable or totally meaningless.

This is confusing. Surely accusations of non-falsifiability are advanced under the assumption that non-falsifiability implies a lack of content that makes being right impossible. To say that Fukuyama is not even wrong is to say that his argument is sufficiently elastic to evade evaluation and thus meta-discursively wrong. For myself, I’m here to tell you that Fukuyama is wrong, wrong wrong: to the extent that The End of History expresses a firm argument, it’s that human civilization has a teleological purpose and that liberal democracy represents a transcendent culmination of that purpose, one that we have not reached fully and may never reach fully but one that will prove more attractive to most people than any alternative in perpetuity. And that’s wrong because the sweep of human possibility is vastly larger than any person can ever understand from their own limited and contingent perspective within one tiny expression of that possibility, like our current moment. Will human beings still value democratic control of government and the liberal ideal when sentient androids perform everything we now think of as labor, thus fundamentally reorienting what government even is or does and what rights really are? I don’t know. Resnikoff doesn’t know. Fukuyama doesn’t know.

In general, I find “rule by machine” to be a profoundly likely evolution of human society, given our trajectory, and I'm surprised it's not discussed more. The average person cares much less about autonomy than about comfort. More likely, the unimaginable future is just that, unimaginable to me and you.

What’s so frustrating about all this is that Fukuyama could easily have made a more limited and contingent version of his argument that even I wouldn’t reject - “for now, under present conditions, with human societies looking the way that they do, liberal capitalist democracies will appear more attractive than any alternative to most people and most governments will attempt to at least appear to represent that ideal.” Sure. No argument here. The trouble is that such a thesis isn’t sufficiently provocative to inspire these kinds of arguments, decades after the fact, or to sell books. I think Fukuyama is a very sincere guy and I don’t doubt that he’s advanced the end of history theory because he believes it to be true. But I also think he is a textbook example - no, the textbook example - of how the marketplace of ideas pushes people into rhetorical extremes that they then have to defend through the kind of equivocation and muddying of the water that haunts so many defenses of Fukuyama. If you call your book The End of History, people are going to react as if you’re talking about the end of history! Doing media hits for years where you casually talk about the culmination of human affairs and then defending what you’ve said by constantly saying, “well, I didn’t really mean the end of history….” It just all seems so disingenuous.

And this conversation does have teeth. Fukuyama was an early neoconservative, and an influential one, a fact that Resnikoff ignores. He has since backed off somewhat from that philosophy, but the messianism and crusader mentality that did so much damage in the hands of the neocons clearly animate The End of History. As a neoconservative, Fukuyama was generally supportive of the notion that the United States should help establish this hegemonic vision of liberal democracy through force, a philosophy that has conservatively speaking killed hundreds of thousands in this century. Somehow this element of Fukuyama’s worldview always goes undiscussed. And yet it’s a perfectly coherent consequence of the concept of the end of history. If you think liberal democracy is this shining exemplar of what humanity is meant to be, it’s easy to think that you have to spread it through force of arms. A few dead Muslims are small price to pay to secure the end of history.

I’ve argued that Fukuyama’s perspective is too narrow, too limited, too particular. And that is indeed the heart of my critique. But you could also argue it the other way; you could argue that the concept of the end of history is so abstract and removed from the reality of actual human affairs that it’s fundamentally inhumane. After 9/11, some suggested that the attacks had proven Fukuyama to be wrong - how could one witness the carnage and declare that history had ended? In the years since, as “the war on terror” has receded from public consciousness, Fukuyama’s defenders have gloated that he was proven right after all; Al Qaeda offered no durable alternative to the liberal democratic order. Which is not incorrect! It merely misses the point entirely. What the attacks and their aftermath demonstrated was that the abstraction that is “liberal democracy” operates at such an immense altitude above daily human life that talking about the end of history - however cute you want to get about what you mean by “end” - becomes irrelevant. In response to 9/11, the United States invaded Iraq, directly causing the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis and resulting in the total demolition of the country’s civil society. You might, if you were a sociopath, have pulled an Iraqi child living through the horrors of the war aside and sternly intoned to them “regardless of the outcome of this war, the world will advance towards liberal democracy, the end of history.” And I imagine they would say, one way or another, “my God, who cares?”

This argument always reminded me of this Calvin and Hobbes comic:

https://www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes/2018/10/25

I still think Taleb has the most succinct and effective dismissal of this stuff: History was shaped by black swan events that no one predicted. The future will also be shaped by black swan events that no one predicts.

A decrease in volatility is not a sign that risk has decreased. It often means you are measuring wrong, or more likely, there are hidden factors you don't know about until too late. It always look obvious in hindsight, but no one gets it right as it's happening.