Layoffs Cannot Prove the Efficacy of AI

corporations do stupid things

Derek Thompson’s podcast has been, for me, something of a bellwether for the broader conversation about LLMs and “AI” - there’s real and growing skepticism about these technologies, but as is true in the broader national mood, there’s a limit to his imagination that compels him to recursively step back from the ledge of considering the most pessimistic scenario. As the predictions of the loudest AI evangelists have continued to fail to come true, events like Sam Altman tweeting a picture of the Death Star right before OpenAI released a version of GPT universally regarded as underwhelming, there’s been grudging acceptance that maybe skeptics have a point. And yet there’s still this dogged refusal to grapple with a clear possibility: that while they have some superficially-impressive capabilities, LLMs are fundamentally limited technologies that cannot possibly create the incredible new world repeatedly promised by charlatans like Dario Amodei. We all got way overheated about AI. Derek can’t get there in a way that seems characteristic of our broader media. The possibility just seems too destabilizing; everyone is too invested in this, literally and metaphorically.

On the latest episode of his podcast, he talks with a couple of econo podcasters about the perennial question “Are young people screwed?” (My answer: yes, but no more than young people of every generation are always screwed.) This conversation leads to a disquieting moment - disquieting for me, anyway - in which one of the guests suggests that an upside from the inability of young people to buy houses lies in the fact that they are instead investing what would be mortgage money in other vehicles. Unfortunately, as the guest himself suggests, this money is mostly being pushed into the day-trading app Robinhood, crypto, and sports gambling! In other words, money that would have gone into one of the safest investments people can make, home ownership, is instead going into highly volatile and risky investments. Derek puts a positive spin on it by suggesting that they may be using Robinhood to get into safe index funds, but I mean… really? Generation Roulette Wheel is getting Robinhood to park their money in a broad S&P 500 Vanguard fund and saying “In thirty years I’ll be sitting pretty”? I am, to put it lightly, highly skeptical.

Setting that aside, though - the question of young people’s financial fortunes inevitably becomes a conversation about AI, as all economic questions must. And here there’s a great deal of discussion about the possibility of AI-driven job loss. Derek and the guests rightfully point out that it’s actually not possible to tell if recent layoffs are driven by AI; as they suggest, the post-pandemic hiring frenzy that prompted talk of a “Great Resignation” would seem to have been a significant overcorrection, and then the sudden ratcheting up of interest rates after a decade of artificially-low borrowing costs made all that hiring even more problematic. That layoffs have followed in a higher interest-rate environment where the vast majority of the economy is experiencing sluggish growth and a tiny handful of firms are generating all of the profit - well, that’s not at all surprising. But I want to also extend this a bit: it’s not just that we can’t prove that recent layoffs are the result of AI, it’s that even if companies are intentionally and specifically laying people off because of AI, that is not at all proof that AI can do the things it is purported to do.

Even if you could, miraculously, trace specific layoffs directly to AI deployments (and you can’t, not with the clean causal clarity people want), that would show only that employers believed that the technology was effective, transformative, and capable of being sensibly deployed, not that it actually is effective, transformative, and going to be sensibly deployed. Companies lie, and they also make mistakes.

First: corporations do dumb things. This is not a rhetorical flourish; it’s an economic baseline. Corporations are fallible organizations full of executives operating under short-term financial pressures, quarterly targets, and the desire to signal to investors. They hire during one macro regime and fire during the next; they adopt shiny technologies because of hype cycles; they cut costs to meet earnings expectations without any systemic audit of whether that’s the least-bad path forward. Pointing to a firm’s decision to replace a team with some AI pilot is evidence of human decision-making, not of technological competence. The conclusions you can responsibly draw from a CEO’s memo are about corporate priorities and PR, not about whether an algorithm can actually do the job.

Second: there are a lot of things that look like technological displacement but are really managerial reallocation. After the pandemic, many firms found themselves overstaffed relative to a reconfigured demand curve. Some of that overstaffing was genuine mismatch - new patterns of consumption, real declines in certain lines of business. But a lot of it was solvable by mundane managerial actions: redeploying workers to new tasks, trimming layers of dysfunctional middle management, investing in training. Blaming AI lets management externalize accountability for those choices. “We had to replace workers with hyperefficient AI to maximize #shareholdervalue” is a better headline than “We misread the post-pandemic economy and overhired, whoops!” - and it allows firms to appear technologically modern while dodging responsibility for poor forecasting or sloppy personnel policy.

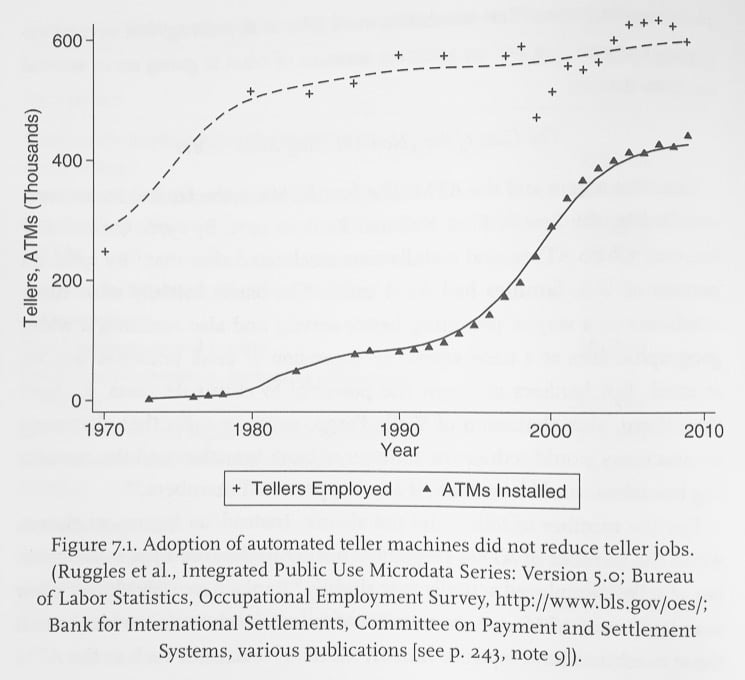

Third: the history of automation is littered with retreats and reversals. From car rental check-in counters to customer service chatbots to self-service kiosks, companies have repeatedly bet that software would make certain classes of frontline labor dispensable, and then had to backpedal when service quality collapsed, regulatory headaches mounted, or customer behavior refused to bend to algorithmic will. Famously, ATMs were deployed with widespread predictions that the job of bank teller would disappear. I mean, that was the whole point! Robot tellers were there to do the jobs that human tellers were once employed to do and, though the initial capital outlays would be significant, in the long run it would be more profitable. And yet that’s not what happened: for decades, the rate of human bank teller hiring increased as more and more ATMs were deployed. It turned out that customers wanted to do certain things with ATMs but were only comfortable doing others with human tellers. Automation didn’t destroy human employment but lived alongside it. That growth in teller jobs has attenuated somewhat in recent years, but the point remains: the assumption that the rise of an automated alternative is going to result in the death of human jobs has been proven false again and again.

You could also look at the automotive sector, which many people would regard as the clearest example of an industry with a great deal of job automation - while there has been vast automation of core tasks in the manufacture of cars, there have also been clear examples of certain jobs being automated and then deautomated. Here’s a recentish paper titled “Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor,” which is simply not what you’d expect based on current rhetoric. Recent history has plenty of examples of attempts to automate that fizzle out and were reversed. Those failures are not footnotes; they’re central data. They tell us two things at once: one, technological substitution is hard, because work is often a bundle of tacit, social, context-dependent skills that are trivial for humans and fiendishly hard to reduce to code; and two, organizations will nonetheless frame their errors as technological inevitabilities when it suits them.

You will hear, insistently, that “this time it’s different.” And, hey, maybe it really is; there have been real improvements in machine learning and automation. But corporations can and have and will reduce jobs out of sincere belief that code can replace humans even though that sincere belief is wrong. The effectiveness of technology is not proven by announcing it in a board memo or by citing a reduction in headcount. Effectiveness requires sustained operation under messy real-world constraints: reliability, maintainability, the ability to handle edge cases, integration with human teams, and the political and regulatory environment. Corporate statements about AI-driven efficiency are performative acts; they’re aimed at markets, not at rigorous verification. That is a huge part of this, the fact that these corporations are more committed to manipulating their stock prices than anything else. The things they say aren’t reliable because they feel constant intense pressure to maintain a facade for the markets.

Blaming AI is cheap and easy. It’s a narrative that absolves executives of responsibility while offering the public a neat villain in an era of profound anxiety about technology. “AI did it” is preferable to “we cut staff because we wanted to hit the Street’s target this quarter.” It signals cutting-edge modernity in a way to placate analysts while deflecting scrutiny of leadership. Meanwhile, workers and communities shoulder the real costs. If your anxious neighbor complains to you about job losses and how “the robots are taking over,” you should ask a follow-up question: did the company replace that position with well-engineered, field-tested automation that demonstrably improved productivity, or did it simply reduce headcount and wave a press release around?

You cannot prove the efficacy of a technology by pointing at the consequences of choices made by fallible institutions. It’s an elementary mistake of induction: observing a change in employment after an organizational decision tells you about the decision, not about the underlying causal power of any particular tool. If a grocery chain lays off its human deli workers and replaces them with a meat-and-cheese dispenser, blaming an inventory-management AI, it’s entirely possible the chain wanted to cut costs and chose a convenient poster-child for the choice. If they have to reverse course, it’s possible the technology was incompetently deployed; it’s also possible the technology just doesn’t work. Whatever the case may be, the causal arrow is ambiguous. Proper proof would require careful counterfactuals, controlled comparisons, and replication across contexts - the stuff of rigorous policy research, not corporate press copy. You can’t establish the transformative power of technology by citing the consequences of human choices.

The fact that Facebook changed its name to "Meta", betting hugely on a virtual reality boom that fizzled so utterly, is testament to how fallible such tech predictions can be. I don't know how they continue to give quarterly updates to investors and keep a straight face, when their own freaking name declares "we have no idea what the next big thing is."

Then again, I also remember the pre-dot-com-boom days of the internet, with lots of commentators smugly declaring that "few people will feel comfortable enough with e-commerce to displace real brick-and-mortar stores." Yeah, real-life stores didn't go away, but suddenly Amazon is the 300-lb. gorilla, with a market cap three times bigger than Wal-Mart, the previous reigning champion. Technology CAN completely disrupt a market. Which is why everyone keeps holding their breath for the next big thing.

The entire history of the stock market is a series of wild bubbles.

That said, it was written of old that "nobody ever lost their job by buying IBM." That logic holds for speculative manias as well. Management don't lose their jobs for doing what the all other corporate lemmings did at the time.

John Maynard Keynes, “A sound banker, alas, is not one who foresees danger and avoids it, but one who, when he is ruined, is ruined in a conventional way along with his fellows, so that no one can really blame him.”