Kendrick Lamar: Talented Musician, Provocative Figure, Emperor of the Whites

there is no Black rebellion that white people cannot appropriate and commodify

Because I’m very clever, I would like to talk about Kendrick Lamar by first talking about something else. Please consider this missive from The Atlantic’s in-house music writer Spencer Kornhaber, in which the author is forced into a position he clearly hates: compelled by reality to acknowledge the unchallenged dominance of pop music today.

Kornhaber is one of the true stalwarts of the Aging White Male Poptimist cadre, a very competitive space. His essay is of a piece with a lot of recent work that’s lately emerged from poptimism, in that it’s powered by cognitive dissonance. Kornhaber appears unable to keep pretending that pop music is an underdog, but he also clearly seems to be terribly anxious about saying that pop music is not. As his own analysis of the Grammys proves, the absolute cultural and commercial and social hegemony of the most bubblegum of pop music is now so overwhelmingly obvious, and the social costs of criticizing that music now so well-established, that even hardened propagandists like Kornhaber can’t quite maintain the old ruse anymore. “Pop music is a disrespected and marginalized genre, and rock fans use their dominant position among critics and award show voters to maintain that marginalization” is now so plainly absurd, so absolutely and utterly and plain-facedly untrue, that even a shameless practitioner just can’t tell the old lie anymore. They don’t even bother to show the Grammy for Best Rock Album on the telecast anymore. Kornhaber clearly doesn’t know how to be plainly honest about this present reality of total, unbroken, undisputed pop music victory. So he just sort of squirms around and doesn’t directly admit the dominance of pop music while describing the dominance of pop music. That’s become a common move, and not just among poptimists.

We live in a culture that cannot celebrate anything without celebrating it as an underdog, no matter how absurd it may be to bestow that status. That’s why people go on Reddit and sincerely claim that liking Star Wars, the most successful mass media franchise in world history, makes them members of a beleaguered minority class. It’s why people in “outsider” media who champion Donald Trump still posture as dissidents during a Republican trifecta. It’s why Travis Kelce, multi-hyphenate celebrity superstar and member of a two-time defending Super Bowl champion Kansas City Chiefs team, still routinely does the “nobody believes in us!” thing. The superior virtue of the most oppressed has worked its way into every corner of our culture. We’re left in this bizarre space where no one is willing to flourish, to succeed, without simultaneously calling themselves an underdog, their talents unrecognized and their tastes disrespected. This is planet “Nobody believed in me!,” and facts never get in the way.

Thus, to pick a paradigmatic example, we still get a thousand thinkpieces a year arguing that Beyonce is terribly mistreated and overlooked - Beyonce, a billionaire with the most Grammys in history, every other kind of award that humanity has to bestow, influence in every sphere of human achievement, multiple films and books about her genius, every material, social, artistic, and cultural laurel we as a society can give. Look how fucking long this list of awards is! The only human being on earth who enjoys a combination of celebration and wealth and access and privilege and power that equals that of Beyonce is Taylor Swift, and both are constantly referred to as disrespected and marginalized underdogs in our most prestigious publications. Beyonce has thirty-five Grammys. What would be enough? Seventy? Seven hundred? Honey, the whole point is that nothing could ever be good enough for her. Indeed, the evidence that Beyonce is an immensely lauded human being is so vast that this kind of talk inspires an admonition I get a lot in my career - you’re right, but we don’t talk about that.

And so now with pop music. The reality of pop hegemony has finally become so undeniable that few are still shameless enough to deny it, but the idea that popular music is a beleaguered subaltern is so baked into our music discourse that people don’t know what to do with themselves. Over the years, as I’ve been one of very few writers who are willing to criticize poptimism and the girly pop Schutzstaffel that enforce it, I’ve connected with a few of the first generation of poptimist writers. A handful in a decade-plus, no big deal. The word that I would use to describe their position now is embarrassed. They’re embarrassed because the condition that they fought so hard to insist exists, that pop music is terribly marginalized and pop musicians an oppressed class no different from racial or gender or ethnic minority groups, has become so eminently and indisputably untrue, yes. But they’re also embarrassed because they can’t admit to the former, and thanks to their own efforts. Many of them appear unwilling to continue to go to the old well, too chagrined to keep repeating the lie that the music world is run by white guys with glasses who live in Williamsburg and love jangly guitars. But they also can’t publicly acknowledge that the tide has turned, either. Turns out they did their job too well.

And that’s how you get middle-aged white men engaging in the painful farce of pretending to have discovered hidden depths in the most wretched pop songs that they once justly ridiculed, why social media is festooned with pasty middle-aged guys who showily disdain the “indie rock” that now barely exists as a genre, constantly talking up that genre’s destructive power like a hype man for the Harlem Globetrotters trying to get you to believe that the Washington Generals are a worthy adversary. Unable to live in the shadow of the generalizations that they themselves traffic in, many savvy white men of a fading vintage must constantly remind the world that they aren’t that kind of white man. They see people making fun of the construct of the deluded white guy and are utterly terrified of seeing themselves in it, so they constantly remind the world that they’re the COOL old white dad, they’re the one who loves singing along to Taylor Swift in the family Subaru, they’re the one who never liked Nirvana in the first place. In all of this, of course, they are more like the old indie snob of their imagination than they would ever admit - they too like music only in contrast with a disdained other.

Which brings us to Kendrick Lamar, a talented musician who has relentlessly cultivated a brand for himself as a politicized-but-rarely-political outsider whose music and persona critique white America - and, in doing so, made himself the darling of white liberals. He is a uniquely American, uniquely 21st-century artist, a talented performer who fits in both awkwardly and perfectly with modern American racial politics, which is to say with the dictates of the United States of DiAngelo. Like Bob Dylan, he has meticulously cultivated a persona through a studied indifference to persona. No other figure in pop culture better exemplifies How We Like Pop Art Today, which is to say, as a signaling mechanism before all else, as an avatar for the self that we want others to see. That all of this is unfair to Lamar the musician, and to his music, I readily admit. But I guess that’s what the money, fame, and critical adulation are for, huh?

Kendrick Lamar just did the Super Bowl halftime show, which is to say, he performed at the biggest concert that’s ever existed. He has now won twenty Grammys. (Madonna has seven.) He has moved something like 50 million “album equivalents” in his career, whatever that means, and is among the ten best-selling rappers of all time. He is worth in the hundreds of millions of dollars. He has a Pulitzer prize. By absolutely endless acclamation by our culture mavens, he’s the victor in a tiresome and pointless feud with Drake, a feud which has produced many tracks by both that almost no one pretends actually constitute good music. He has been the subject of fawning thinkpieces by the dozens, including in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, New York Magazine, and every other publication that reflects the tastes of our brownstones-and-podcasts educated urbanite striver class. Not all of those people are white, of course, but most of them are, and for good or for bad educated white urban liberal professionals have an outsized influence on our conception of white people as a class. And that kind of person, the kind of person with $100 a pop edibles and a copy of Intermezzo casually splayed out on their Noguchi table, is the kind of person who loves Kendrick Lamar. That’s just reality. He’s just your typical Pulitzer Prize-winning, multimillionaire, Grammy-harvesting, New York Times-beloved, godking-to-white-liberals underdog. Which, given that he also exists as a symbol of vague resistance to white cultural hegemony, is a little awkward.

The entire run-up to Lamar’s performance was about what a consummate outsider he was; that outsider status is at the core of his entire public persona. What could ever codify outsider status better than performing at the Super Bowl, the burning white center of apolitical mass American culture! One would think that this was all self-refuting, right, that a guy standing in front of 120 million people and performing for them while they drink hard seltzer and deliriously refresh FanDuel could not still be a rebel. But the heart wants what it wants. Zack Cheney-Rice observed, in a retrospective of Lamar’s journey, that “By the end of 2018, he looked like the rare Black popular artist who was able to have his cake and eat it, too — lavished with praise by the upper strata of racist institutions that he simultaneously seemed to be subverting.” On the level of basic sense, we should probably insist that no more subverting is happening. But if I tap into the zeitgeist, and recognize that all of these concepts are just a wrestling with feeling, the way people sincerely tell themselves that going to a Taylor Swift concert alone as a 37-year-old is a revolutionary act, well….

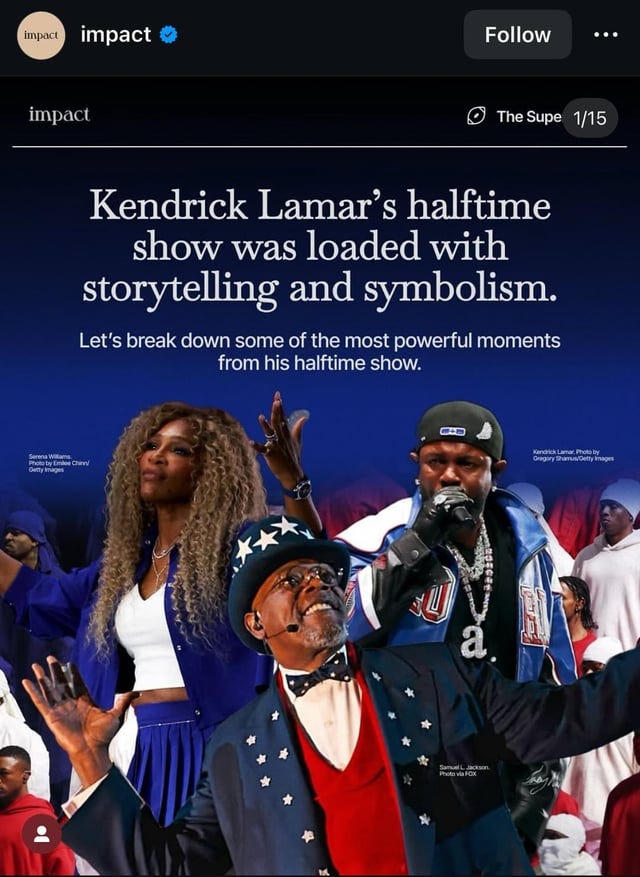

I thought Lamar’s Super Bowl performance was, you know, fine. As a few other brave souls noted beforehand, he was always a bit of a strange choice; for all of his commercial popularity and immense awards success, Lamar is not a musician who makes a great deal of hook-heavy music, and since Super Bowl performances are essentially medleys they inherently reward strong hooks. But if our artistic culture industry believes in anything, these days, it’s in the sublime deliverance inherent to Kendrick Lamar existing, so these concerns were muted. Lamar seemed a little uncomfortable up there on stage, and I thought the theatrics with Samuel Jackson were profoundly thirsty, the work of a guy who’s trying very hard to make some sort of subversive political statement but finds that his culture is giving him very little to subvert. I have sympathy; nobody really knows how to be a political subversive anymore, certainly not through pop culture. But he does bring accusations of political incoherence down on himself through a lot of vague gestures and, especially, by collapsing the distance between his political messages and his trashy feud with Drake - having Serena Williams come onstage to crip walk and in doing so, uh, heal the racial trauma she received for doing the same dance at Wimbledon, or whatever. (“Two wrongs, one personal, the other racial, righted at once!”) But also to tweak Drake, who Lamar insists is beneath him.

Again, the comparison that jumps immediately to mind is Bob Dylan. Like Dylan, Lamar seems more interested in being perceived as political than in politics; like Dylan, Lamar’s refusal to fully commit to a comprehensible activist identity is no doubt good for his music and good for his brand but does open him up to fair criticisms of embracing a cynical form of idealism. Like Dylan, Lamar is a dogged cultivator of an image of himself as someone who does not care about his image.

There should be no particular mystery in a 43-year-old metalhead like me not being much of a Kendrick Lamar fan. Once upon a time the norm was a kind of musical detente, a spirit of mutual disinterest across fans of different genres; saying “I’m a metalhead” would have been sufficient for most people to simply nod and understand that Lamar was not an object of particular interest for me. But alas, here again we live in a world of musical appreciation that the poptimists have made, and simply not having an opinion on popular artists is not an option. (To suggest indifference towards Swift is no different from directly insulting her; go on TikTok and try it.) The idea that any one person’s taste is individual and by its very nature incompatible with the tastes of others, a healthy attitude that provokes diversity and the exploration of niche interests, is dead. And its death is all bound up in a phenomenon of deep relevance when considering Kendrick Lamar: nominating our pop culture tastes as stand-ins for our politics and thus as metrics of our character. The idea that your moral value is determined by what you do has given way to the assumption that your moral value is determined by what you like. If you’re an aging dad who likes Sabrina Carpenter, you must be an open-minded and discerning feminist. And if you’re a white person who likes Kendrick Lamar, well, you must have all the right attitudes about race.

I’ve written about this plenty before and I don’t want to bore you, but the fundamental point I find indisputable: many white people, even many savvy white people who are into politics, loudly embrace Black art and Black artists because they believe that doing so will mark them as The Right Kind of White People. In the late 2000s a lot of white liberals needed you to know that they loved The Wire. This fact did not make The Wire any less of a masterpiece, it just meant that I couldn’t go to a certain kind of party for a few years there without encountering a particular sort of white guy performatively loving The Wire, making sure the room knew that he loved The Wire more than all those other people loved The Wire. In the 2020s this symbolic mantle has largely passed to Lamar, who enjoys an ongoing status as an outsider (despite playing the Super Bowl halftime show) and who walks around as a symbol of Black political rebellion (despite his own obvious discomfort with that status); this fact does not make Lamar any less of a star. In the mid-2010s it was Lamar who had so inspired the anxious glasses-clad sensitive white men at parties, he was the one who they were desperate to associate themselves with in whatever vague way. He played the role of avatar for their anxious, usually sincere, sometimes very sweet need to be seen as racially clean, as morally pure. They didn’t embrace him because they didn’t care about not being racist. They embraced him because they genuinely did.

If I say that one of the most relevant things to know about Kendrick Lamar, in 2025, is that white people love him, I will admit that it’s a bitchy, reductive, and unkind thing to say. But you will admit that it is true.

I again acknowledge that what I’m doing here is, in a certain undeniable sense, unfair to Mr. Lamar. After all, he’s just a musician who’s plying his trade in the usual 21st century way - making music, pushing it to streaming, promoting it with appearances, playing concerts. His feud, as pointless and depressing as it is to me, fits clearly into a long lineage in the rap genre. His music wasn’t made for me and yet I still enjoy some of it. The fact that white people often advance Black art and Black artists for ulterior psychological motives shouldn’t and can’t and doesn’t undermine anything about their work. Pointing it out does, though, suggest that they are celebrated for reasons other than the pure ones artists aspire to, and I don’t feel great about that. But every time I’m tempted to just drop this observation about the relationship between white audiences and Black artists, I’m again reminded of a weird and annoying dynamic about this, the precious and attention-begging insistence that nothing is ever good enough for those artists. Consider this take on Lamar’s Super Bowl performance and the supposed failure of the white audience to be moved to a state of appropriate rapture:

I’ve read some wild critiques of Kendrick’s performance. Not just not getting it, that’s ok. That’s why I write this. But there’s a certain hubris, a certain nonchalance to the hubris, that dismissive tone. Like there’s black and white right / wrong, and this performance was black and wrong. In a pass / fail analysis, it failed. It’s really scary reading these. The hubris lacks any openness to one’s not seeing everything. The hubris says all things must appease their taste and sensibility. The hubris leaves no room for other people living entirely separate experiences to have anything they enjoy. Your enjoyment sits above all other priorities.

I could point out that this is exactly what I’m saying about taste, that where once taste was valuable precisely because it was constrained primarily by the sincere and organic reaction of the individual to the art, now taste has become homework, a kind of obligation. But even aside from the right to an individual response, sticking instead to the broad public reaction not only to the halftime show but to Lamar’s entire career … really? You look at Kendrick Lamar, and you look at what white audiences have made of him, and you find it dismissive? You think he’s been treated with insufficient reverence? Here’s some headlines about Kendrick Lamar just from The New York Times, the most reliable chronicle of the tastes and self-conception of America’s white elite class.

The World of Kendrick Lamar, in 6 Key Performances

‘Not Like Us’ Reinvented Kendrick Lamar. Is the Super Bowl Ready for It?

Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl Halftime Show: The Peak of All Rap Battles?

Lamar’s stagings have grown more elaborate, and ambitious.

Kendrick Lamar’s Victory Lap Unites Los Angeles

Kendrick Lamar and Drake Battled Toe to Toe. The Winner Is Old School Hip-Hop.

Who’s Afraid of Being Black? Not Kamala, Beyoncé or Kendrick.

Kendrick Lamar Rides a Rap Beef All the Way to No. 1

How Kendrick Lamar’s ‘Not Like Us’ found a home throughout college football’s space

How Kendrick Lamar Out-Drake’d Drake

Kendrick Lamar’s New Chapter: Raw, Intimate and Unconstrained

Kendrick Lamar on His New Album and the Weight of Clarity

Kendrick Lamar, Hip-Hop’s Newest Old-School Star

It may seem impossible, but I could keep going, and going, and going…. And of course that’s all from just one newspaper. Do these headlines seem, what, insufficiently reverential? Disdainful? In fact they seem designed to project the attitude that words struggle to properly express Lamar’s outsized genius. A review that’s about as negative towards Lamar as the NYT is ever willing to go still insists that “when Lamar is under-delivering… the air fills with expectancy: Surely more is just around the corner?” This is how a writer caters to middlebrow consensus, by embedding criticism in a broader bit of hagiography. Kendrick Lamar doesn’t fail, he only momentarily disappoints. And this is why I can’t let go of the true-but-unfair-but-true observation that Lamar’s career as a rapper has benefited immensely from Lamar’s career as a reflection of what white people hope to see in themselves: because the way we do music appreciation now leaves no space for the thing itself. For the performance itself, a halftime performance that felt a little low energy, that contained antic choreography that stood somewhat awkwardly next to a performer who tends towards minimalism, that was interspersed with Samuel L. Jackson making some sort of vague point about the hypocrisy inherent to American patriotism. The halftime show was fine. The trouble starts when it becomes socially dangerous to say that that’s all it was.

And I would like to free Black artists from those tiresome symbolic expectations, a well as to free the audience. Elite white opinion embraced Kendrick Lamar as a conduit to #blackexcellence more than a decade ago, and this dynamic exists for the same reason that those endlessly-sweaty old white man poptimists can’t give up the ghost - because white people need to believe that they’re the good white people, just as men need to believe that they’re the good men, and they will create vast industries of art and criticism to suborn those feelings. And it all fuses together in the sense that artistic taste and morality are, ultimately, matters of public consensus, the notion that the politics which are moral and the art which is good are those that have received the blessings of the crowd. The notion of a private morality, like the idea of a personal taste, becomes disreputable in the face of a vision of doing and liking the right things as defined entirely by what other people think. People who work in high schools tell me that there are no subcultures anymore, no punks, no emos, no goths. If that doesn’t depress the shit out of you, I don’t know what to tell you. And that’s what happens when we act like personal style and tastes are subordinate to the moral fads of scolds.

A figure like Kendrick Lamar is important and telling because the insistence on seeing his music as moral instructions for people who went to Brown and shop at the Grand Army Plaza farmer’s market makes political morality just another mass product, just another subject for conspicuous consumption. It’s an ugly reality: people project political meaning onto pop culture because they feel incapable of creating real change; they read pop culture objects through their implied politics because they don’t know what it’s like to have an actual artistic taste. All they have is someone else’s idea of good politics, and in the case of Black artists, that idea is almost always run through the prism of white anxiety. “Lamar is the rare popular musician who receives almost universal acclaim, not only artistically, but often as a kind of paragon of virtue,” reads the NYT review I quoted from above. He is indeed. But is that good? And will we ever be in a position again where taste is taste, where people expect others to dislike the artists they like, where nobody feels like they have to love an artist because the internet told them to?

I can’t speak for the man. But now, with no more critical or commercial worlds left to conquer, I would expect that Kendrick Lamar might appreciate the opportunity to just be a rapper.

Also, Freddie, I love you man, but sometimes I feel like we're in a thematic loop here. Perhaps this is intentional, or not, and you've raised good points about poptimism, AI skepticism, and the parlous state of mental health reporting. Raising good points at each step.

The thing is, even though you're writing about these themes that you seem to care a lot about, we're not seeing a lot of *new* insights. It's good for new subscribers, true, but maybe there's some other things that are capturing your attention, too? Because I know I'd dig some more variety.

We have long since reached the point where winning award after award in times of heavily politicized moments is a distinct countersignal to actual coolness, if not talent itself.

Nobody would dare say Beyonce is a mediocre pop star because it's professional suicide. Yet, listeners have ears that can quickly discern this.

Similarly, nobody would dare come out and say that Kendrick Lamar is a weird manlet with hobbit hands (pax Byron Crawford) with no actual flow. For the same reasons.

The kayfabe is suffocating. If the Trump years accomplish nothing else, it will be putting an end of Hyping Obvious Mediocrities for socially and politically promoted reasons. Just let people enjoy shit, and let the actual recognition and praise fall where it may organically again.