This is the latest monthly guest column from Phoebe Maltz Bovy, who writes a newsletter about reruns and podcasts with Kat Rosenfield at Feminine Chaos.

A church book sale in my Toronto neighborhood had The Official Politically Correct Dictionary and Handbook, the updated 1994 edition of Henry Beard and Christopher Cerf’s popular 1992 book. I always gravitate to books like that, to see whether there is in fact anything new in this world, and to remind myself that the (overly simplistic) answer is no. (See also the 1995 compendium, Debating Sexual Correctness. The #MeToo discourse existed prior to #MeToo, and indeed prior to discourse.) Also, we’re living through a kind of 1990s revival, fueled I suspect by nostalgia for pre-Covid, pre-9/11 times, or maybe just by teenagers’ timeless desire to dress the way everyone did 30 years earlier.

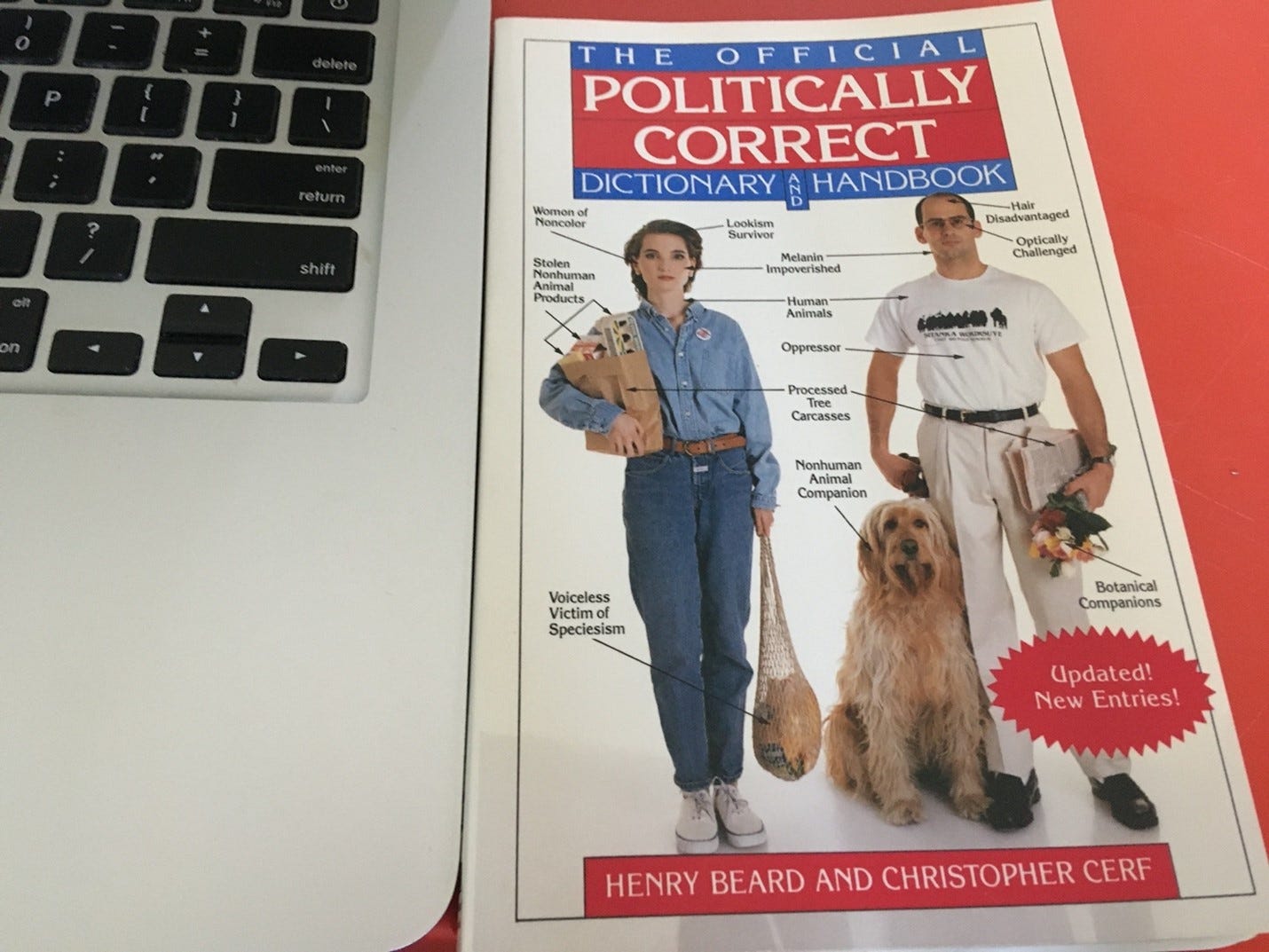

The front cover of the PC dictionary book shows a man, woman, and dog, affixed with labels such as “hair disadvantaged” (he’s bald), “woman of noncolor” (she’s white) and “nonhuman animal companion” (is shaggy dog). All three, though especially the woman and the dog, would not be out of place in a 2022 farmers market. (Again, cyclical fashions.)

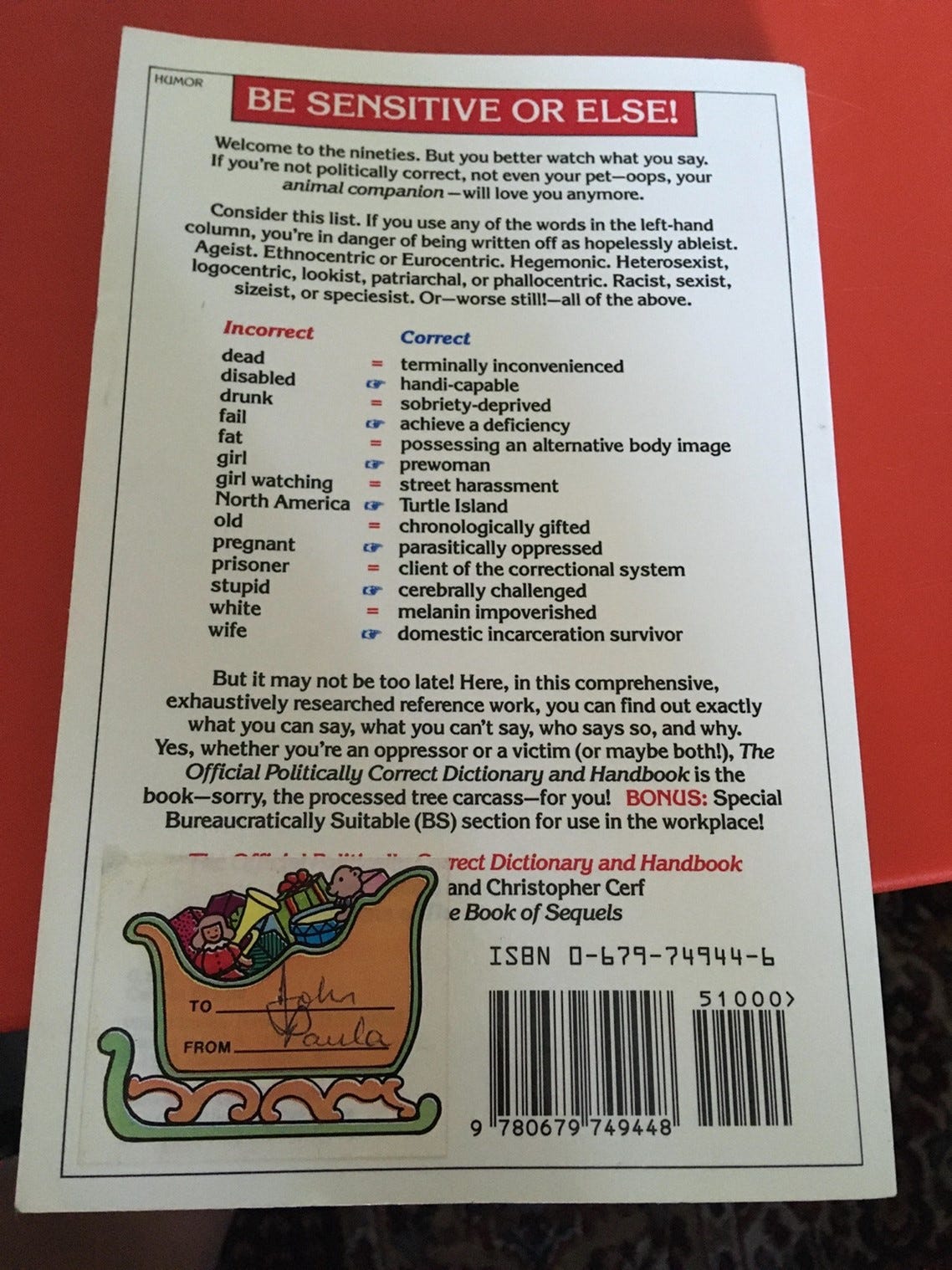

The back cover bears a warning, “Be sensitive or else!,” with the follow-up, “Welcome to the nineties. But you better watch what you say. If you’re not politically correct, not even your pet—oops, your animal companion—will love you anymore.” Beard’s author bio begins, “Although Henry Beard is a typical product of elitist educational institutions and a beneficiary of a number of negative action programs, he has struggled to overcome his many severe privileges.” Cerf’s: “Christopher Cerf is a melanin-impoverished, temporarily abled, straight, half-Anglo-, half-Jewish-American male.” Privilege disclaimers, in the early 1990s! I had to have it.

A compare-and-contrast of 1990s PC and contemporary so-called wokeness could go in any number of directions and fill volumes. To prevent things from getting out of hand, I’m restricting myself, mostly, to a too-close read of this one book, and asking only a few questions: Granted that lots of what seems new is in fact old, what do the differences indicate about the specificity of each moment? Did PC have the same place in the culture as wokeness later would?

I’ll get to all (some) of that in a moment, but first, the fact of the book itself: Could something like this exist today? The existence of The Babylon Bee Guide to Wokeness suggests yes, but lighthearted humor does not exactly define the anti-wokeness backlash. Rather, it’s a mix of earnestly concerned progressives who think the left is shooting itself in the foot (hi), conservatives delighted that the left is shooting itself in the foot, and conservatives afraid that (or opportunistically stoking fears that) critical race theory and drag queen story hours and so forth announce the apocalypse. It’s not that critics of wokeness are humorless, or even that there’s no good anti-woke humor. (There’s surprisingly a lot in Kim’s Convenience, a contemporary Canadian sitcom about a Korean immigrant family.)

But humorlessness dominates, perhaps due to increased polarization, or a sense that the stakes are too high to joke around. Woke and anti-woke alike gravitate towards utter seriousness. So committed is Florida governor Ron DeSantis to stopping woke that he is trying, unsuccessfully thus far, to have a “Stop WOKE” Act in his state. Florida, he has said, is “where woke goes to die.” Then on the other side you’ve got Hannah Gadsby declaring the very act of creating comedy that’s funny a problematic choice. Censoriousness against censoriousness.

Meanwhile the legacy of 1990s PC is the mockery it inspired. As I understand it, PC had its heyday as parody-fodder in the early 1990s, when I was in elementary school. Politically Incorrect with Bill Maher launched in 1993. Politically Correct Bedtime Stories, fairy tales updated satirically in keeping with then-contemporary mores, appeared in 1994, the same year as campus comedy PCU. South Park, at 1997, was a relatively late addition. And this was not just in the States. Waiting for God, a truly wonderful British sitcom which ran from 1990 to 1994, made frequent reference to political correctness, as encountered by skeptical retirees who found it both silly and patronizing.

That, then, is the context for the PC dictionary. It’s part of the very 1990s thing of finding liberal-arts-college mores hilarious. Who was the audience for it? Given the time period, it can’t have been the very online, who at that point barely existed, and given that it was apparently a bestseller, it can’t have been all that niche.

I began reading the PC dictionary with certain assumptions, some affirmed, others not at all, about what would seem different or dated. My initial hunch had been that 1990s PC was more about manners and, as such, didn’t frighten anyone. But that’s not quite it. There was the PC police or the thought police. There were sexual harassment suits, and anxious jokes about being subject to those. And the term “political correctness” is itself originally a reference to totalitarian speech restrictions.

While the specific term cancel culture wasn’t used, the concept existed, and was indeed driving the cultural concern. The book opens with an account of environmental ethics professor Roderick Nash having a “formal sexual-harassment charge” filed by some students, after he’d made a risqué joke in class. Exactly how much employees had to fear (or irrationally feared) getting fired for wrongthink then versus now is beyond the scope of my current blathering-on, but the point is that the fear and reality both already existed.

Best as I can tell, PC wasn’t a force dividing society, Dreyfus Affair-style, the way one’s stance with respect to wokeness can be. (People who remember the 1990s better than I did, or just who didn’t grow up in apartments: were there rival yard signs? I don’t mean for politicians, I mean “In this house we believe”-style.) The general reality was just that certain liberals, on college campuses or in rich-progressive neighborhoods, were uptight. Others, equally liberal, had a different, more low-key approach and could take a joke. Someone, somewhere, doubtless used womyn instead of women. But the chances that you personally would be shamed for writing “women” were remote. Maybe you’d get in trouble for saying the wrong thing. But maybe no one would care if you questioned the whole project of punishing people for saying the wrong thing.

The PC dictionary really is just that, a glossary-format guide to the PC and non-PC terms for various genders, animals, concepts. The entries often have footnotes, some leading to university statements and the like, others to earlier parodies.

If the exact terminology sometimes differs, many of the concerns of that era overlap with ours. Apparently “writing about communities of which one is not a member” was frowned upon. There are gender-neutral pronouns, but it’s “tey” and “tem” rather than “they/them.” “Sex worker” is preferred over “prostitute,” “houseless” over “homeless,” “enslaved person” over “slave.” “Swapping sex partners” is to be called “consensual nonmonogamy.” Person-first language (a person with a condition, etc.) comes up quite a bit. Considering this was all before social media, the sheer Tumblr-ness of it all is striking.

As for differences? There’s a lot more about animals than one sees these days: veganism, but also speciesism and pet ownership. And while gender neutrality comes up frequently, intersexuality occasionally, the entire concept of transgender, transsexual, or non-binary identity never appears. It’s the gender neutrality, I suppose, of 1990s feminism, the idea that it’s sexist to draw attention to a woman’s gender by using a term like actress, rather than that there are people who personally refuse male or female pronouns and require a different set, or whose own pronouns changed in the course of their lives.

Characteristic of 1990s PC, aesthetically, euphemism was key, as in stuff like “vertically challenged” for “short.” Along with the main dictionary sections is a much shorter one, taking on governmental and corporate doublespeak. The common ground is mocking euphemistic speech: “Aggressive defense” is the “U.S. military term for an aggressive offensive attack.” Euphemism puts off the authors, it would seem, both because it’s silly, and because it’s a refusal to speak plain truths.

There are bits of the book where it’s hard to see what the authors found worthy of caring about. Some changes that looked odd enough to remark on then have simply entered the language, such as use of “chair” rather than “chairman,” or “personal assistant” replacing “secretary.” Sometimes language changes and it matters. (While it doesn’t especially to me personally, the “pregnant people” vs “pregnant women” discussion of our times matters to plenty of people.) Other times, whatever.

But the point of the book feels about as 2022 as it could. There are the defenses of free speech, which, yes, but more powerful, and more relevant, is the critique of PC’s fixation on language over substance, and indeed in obscuring the absence of substantive change:

“It’s easy to see why so many reformers have forsworn a unified assault on such distracting side issues as guaranteeing equal pay for equal work; eliminating unemployment, poverty, and homelessness, counteracting the inordinate influence of moneyed interests on the electoral system; and improving the dismal state of American education, all in order to devote their energies to correcting the fundamental inequities described in these pages.”

OK, so verdict time: PC is wokeness, wokeness is PC, and, per the cover models, normcore is forever. Still unanswered: does the fact that PC faded the way trends do, of its own accord, amount to a challenge to the wisdom of (for example) attempting to legislate against wokeness now? It just might.

Wokeness has something for everyone, an all you can eat buffet where everyone gets a plate. Conservatives get their dose of rage porn, the "woke" get to signal that they're one of the good ones and get to make some hay out of exposure to liberal arts education, cynical dirtbag leftist types get to mock the woke for being absurd even though they tacitly share many of the same views, elected leaders left, right, and center get readymade talking points.

And everyone gets to ignore the myriad of disasters unfolding around us as the wheels fall off the whole system. We get to fight the battles of the 90s today like Civil War reenacters, because we have no idea what to do about what we are currently facing.

"does the fact that PC faded the way trends do, of its own accord, amount to a challenge to the wisdom of (for example) attempting to legislate against wokeness now?"

Maybe, but it's also possible that 90s PC was always limited in its power by a still-entrenched pro-institutional mindset that most people had, especially toward higher ed. It seems like the difference between then and now is that now you really can bring institutions to their knees over "womyn," "pregnant people," etc. And part of this has to do with how hollowed out those institutions are by transactionalism, fear of market reprisals, etc. Policing people's speech is amusing if you're just a random scold. It's a lot different if you've suddenly got the ability to fire, de-license, or even imprison people.