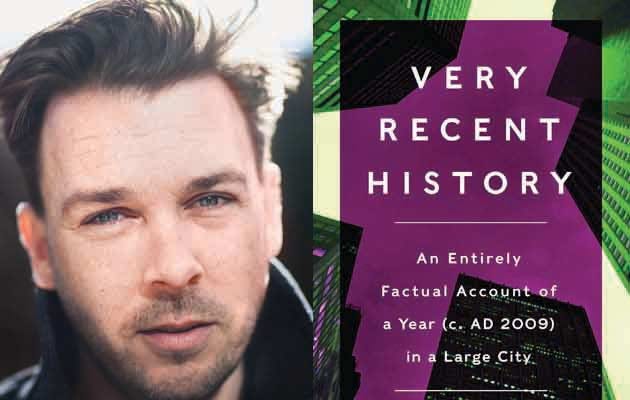

Imagine If Everyone Who Tried to Write Like Choire Sicha Had His Emotional Integrity

It’s often been said that if there is anything like a default prose style for the internet, no one has influenced it more than Choire Sicha, the former Gawker editor and Awl founder and current New York editor. This may not sound like praise; the default style of the internet is pretty damn annoying. But the point is not that the average style really mimics that of Sicha but that it’s a warmed over photocopy-of-a-photocopy of Sicha’s voice. For many people his run at Gawker was what defined that website, and from my recollection when he founded the Awl with Alex Balk he evolved that style into something more mature and quiet, which is what we should hope adults do over time. People try to mimic him and come up with something like superior disdain, but I no more blame him for that than I blame Quentin Tarantino for bringing us Boondock Saints. Influence is an unruly weed; it grows in whatever directions it wants to.

I’m afraid I don’t have that one key link to someone else saying what I’m saying, the internet’s greatest mark of rigor in an argument. Mostly I understand Sicha’s influence because I talk to other writers who recognize it, and it kind of floats out there in the ether. The obvious choice for corroboration would be this 2013 New Yorker article; it says, with the gravitas common to that publication,

Sicha has spent the past decade developing what has become the lingua franca of the Internet… Sicha is an auteur; his peculiar, particular sensibility appears in everything published on his site—and, somehow, in the blogs posts, tweets, and e-mails of almost everyone under forty.

So that’s helpful. The trouble is that I don’t really agree with that essay’s analysis of that sensibility, really, other than that it’s peculiar and particular. But I will allow the country’s most respected magazine to do the work of proving that the influence I’m describing isn’t all in my head. This piece in the Verge from a couple years later also reflects on Sicha’s influence. Or you could just take my word for it.

It’s a shame, given this influence, that the droll, world-weary, and subtly lacerating elements of Sicha’s style are what has been so endlessly aped, and not the deeper commitments that underwrote them. For one thing, it’s simply much harder than people seem to think to be dry and cutting, and anyway we are now drowning in such attitude and so it can’t possibly seem anything else than tired. A 2008 n+1 piece contrasted Sicha’s style with “vacuous sarcasm,” and that’s as good a term as any for the default affect of the internet, I suppose. But there’s a deeper failure to understand that the only route to authentic irony, rather than its aforementioned unwelcome cousin, is through the heart. Sicha is living proof that every true ironist is a failed romantic. I think Sicha has maintained an incorrigible desire to see the world in a better light than he currently does. What I think his imitators fail to understand - or, more like, the generations who now imitate the imitators, unaware of the original - is that his best work has always been ringed with kindness. There was certainly an edge to his work at Gawker, and I don’t think he’s ever been above being mean, even now. But as I once said ages ago, there’s a Southern gentility to his voice, even though I don’t think he’s Southern. (Wikipedia is mute on this question, and thus so am I.) It’s hard to define, this kindness, but it’s there.

You know how in that awful Johnny Depp Willy Wonka movie, a kid tells him her name and he says “I don’t care”? That was a very effective demonstration of a stunning failure to understand a literary character. Roald Dahl’s Wonka is indeed remote and cold and strangely unhappy to see the children that he’s let into his factory. But there’s a sense of meticulous manners to Wonka, something I would associate with… old money, maybe? A propriety which engenders respect for others when respect is given. The Willy Wonka of the book would never say something so crass to someone who has just introduced themselves, even someone as annoying as Violet - not just for her, but also because it would be beneath him. We’re finding, in modern life, that when we leave aside conventional manners we aren’t left with some emergent order of mutual validation, but rather with an ethic of self-aggrandizement, an ideology that tells us that we always come first. If old formalities were all for show then at least they engendered a performance of respect, which might have inspired an affection for the real thing. I would so much rather someone be polite to me than they try to validate me. I assure you that this fits into this essay somehow.

Please consider this excerpt of a 2013 piece by Sicha from New York magazine. I have tastefully left out the description of being paid to watch someone take a glass bottle up their ass, but include that reference to entice you to read the whole thing.

We installed the ethos that pedigree was over and all money was now equally valuable. The mythology of Silicon Alley was forced to coalesce for good, with City Hall’s fervor behind it. The start-up culture wars—a fresh beef with the West Coast, except boring!—intentionally pitted us against the weirdo jerks of Palo Alto. The scrunchy-face foxy Foursquare co-founders appeared in Gap ads, clad in mediocre jeans but form-fitting venture capital. You were a good person if you were an entrepreneur. You were creating jobs, until you weren’t. The big floor-through lofts of Broadway between Houston and Spring filled up with inexpensive furniture and even less expensive young people, each with a bitter mouthful of Adderall, each office bright and identical. So far, we’ve disrupted a few things, mostly coffee-related.

A city’s culture is what you see when you walk from a cab to your door. Now it’s all plastic prefab, much of it involving banks, the red glow of Bank of America, the men atop their two-wheeled blue Citibank ads, riding by one of the city’s 500 Dunkin’ Donuts locations. When I moved to New York City, the East Village’s ATM was on Broadway by 9th Street. You had to get there before it ran out of money or closed for the night, or, on Fridays, the afternoon, because it used to be that all the banks closed shortly after lunch on Fridays. (It sucked.)

Maybe New York is so warm, so cozy now that it gives people nothing more to want.

As a five-year resident and longtime visitor to NYC, I am struck by how different this sounds than the city I live in today. But never mind. I share this excerpt for a few reasons. The first is to demonstrate my earlier point that there are registers that are very inviting to young writers, when they’re trying on voices in their work like college freshmen trying on personalities, that are in fact almost impossible for the young to use. There are types of credibility that come only from experience, and even precocious 20-somethings don’t have it. (Come to think of it, it’s much worse if they’re precocious.) It’s not an “I’ve lived in New York longer than you” thing. It’s a “I’ve lived longer on Earth than you” thing.

But I would also like to point out how this passage is critical but free from any kind of clumsy disdain or righteous derision, with nothing meaner than the swipe at the inconvenient hours of the banks of ages past. (The weirdo jerks of Palo Alto are too vague to be insulted; the CEOs are scrunchy-faced, I’ll remind you, but foxy, and I detect no irony there.) The fashion of hip progressive writer types (practically the mandate, honestly) is to mock tech bros ceaselessly and crassly, to assert their moral poverty as well as their failures of style and cool. It’s an absolutely exhausted genre, whether in essay, post, or tweet, yet tuned-in young writers oblige the communal dictate and still take sad waves at deriding NFTs or whatever, perhaps despite and perhaps because of the fact that the war of New York media vs. Silicon Valley tech can only end in one way. Well, observe the paragraph above: it’s remarkably disciplined in its restraint, and for that very reason far more effective than yet another withering putdown about tech bros.

It’s easy to counsel subtlety. It’s much harder to pull it off. And perhaps empathy is a register that’s accessed so rarely, outside of greeting cards, because it’s so often packaged with self-seriousness and cloying sentimentality. But if we’re good enough and we care enough, there are other ways. The essay ends

This summer I heard a rumor about a Bushwick-living recent liberal-arts-school graduate I know. People said he’d quit his day job and was now working for a high-end drug-delivery service, performing services in that sweet spot ranging from courier to gigolo. I hope it’s true so much that I can’t even ask him.

A sufficiently advanced latent semantic analysis would conclude that this light paragraph is not entirely free of irreverence, judgment, perhaps the lightest possible touch of mockery. But it’s also a sincere statement of interpersonal kindness, sweet and knowing, and serves as an effective metonym for a kind of decadence-of-ancient-Rome quality that was unique to New York City in the Bloomberg era. Derision is easy, compassion harder, and compassion that casually evokes the absurdism of late capitalism very hard indeed. I would not trust one writer in ten to do it so well.

I’m not sure if this is woke or unwoke or what, but I do think that being gay has something to do with Choire’s sensibility. He’s only 50, but Choire’s public persona always reminds me of a certain kind of gay man of an earlier generation that you don’t meet much anymore. Oppression does a lot of things to people, some of them good, some of them bad. Speaking of the latter, it delights some of my liberal friends when I tell stories of my father’s old New York friends schlepping up to suburban Connecticut, when I talk about their sensibility and style, developed in the New York of the 1960s and 70s, when the Village was a rough neighborhood and black box theaters didn’t advertise on YouTube. Those same liberal friends often become less charmed and more uncomfortable when I share the bare fact that many of those gay men simply hated women, and not in any kind of charming romcom way, but in a manner that can only honestly be called misogyny. I think you should forgive them; it was complicated. And of course not all, of course not most. But that’s the sort of thing that has been sanded out of the history of the gay rights movement, along with the fact that it was once called the gay rights movement, and sometimes marginalized subcultures breed ugly little hatreds. That’s just the reality as I remember it, though I was only a kid.

But in some happy cases, living under the fear of assault simply for being who you are can generate a kind of broad and wise acceptance of people, a lived-in, unfussy, quiet understanding of the universality of human mess. In addition to the (often very charming) gay men who hated women, in my youth I also knew some who had a remarkable capacity for amused and knowing empathy, who took the experience of being ridiculed and hated and used it to find a broader moral imagination that could encompass a concern for all kinds of human beings. That’s a rare and valuable quality, and one of the few places I find it consistently is in Choire’s writing.

Then a plague came and killed far too many of that generation of gay men, a bit of history that has been relentlessly memorialized and yet which I find has still passed into the mists of memory far too quickly.

We have combination antiretroviral therapy now, and some particularly treasured rights have been extended, so of course things are better. But we also (still) have the trope of the sassy gay bitch, a stereotype which could never reflect the wisdom that came from being pushed into the corner by society and, in those spaces, observing the fullness of the human experience and deciding that no one’s reality was yours to judge. It’s an absurd reference and one I make against my better judgement, but the character Hollywood from Mannequin, now dismissed as a mincing stereotype when remembered at all, is emblematic of a kind of lighthearted friendliness that I once would have called quintessentially gay. A kind of figure who could forgive another for his strange infatuation because he knew the heavy costs imposed by those who refused to forgive what they could not understand. That was a thing, I think. Nowadays no one seems to have the slightest idea what I’m talking about. Maybe I dreamed it all up.

Everyone knows that the internet is a colossal drag that they can’t quit. You unlock your phone and cruelty falls right out and into your heart. So perhaps there was no version of online life that did not devolve into a firing line of bitter, overeducated people who think they’ve been wronged because they never got the accolades that were coming to them, launching one liner after one liner out into the atmosphere, seemingly in an effort to so saturate our environment with blank and witless sarcasm that it corrodes the buildings and poisons the wells, for what purpose I can’t imagine. Every day a new asshole decides that they’re going to be the one to settle all the world’s scores with their Twitter feed or their podcast, spraying little insults feebly around them and hoping that no one notices that behind the arch delivery and the condescending tone there’s a sad sad person who’s too old to be spending their time that way, the only light in their life the sickly glow of a laptop screen that they should have closed hours ago. It probably had to be this way. But I can imagine a different culture, what could have been. I would say it could still be, but we’re too afraid, too scared to try vulnerability, subtlety, reserve, gentleness, a lack of judgment. Which of course is also to say that I can imagine another me, were I not afraid.

Choire has always been kind to me, despite the fact that I can do nothing for him personally or professionally. In return I’ve demonstrated my perpetual talent for being awkward and a pathological failure to be grateful in a way that’s sincere but casual, as is socially expected. Instead I just sound like me, I’m afraid. For example Choire once emailed me a kind note, and thinking that I was being clever I responded by saying he was the perfect fit for his then-new NYT Styles section. Later I learned the job drove him to the point of wishing for death. Whoops! And now I present the most awkward gesture of all, which is this post. I’m sorry, Choire, that you have to put up with this. I really am.