There’s a new Matrix film coming, and people are excited. I get it; the original is beloved, and all our broken culture can produce is pastiche now, so we might as well play the hits. What I don’t get, and have wondered about for a long time, is why the original is beloved. To me, everything about it looks like an embarrassing relic, a mishmash of individual elements that have all aged poorly. And while I write this knowing that people will see it as an expression of contrarianism, I myself don’t feel like it’s provocative or trolling at all. In fact I can’t really understand why my position isn’t the default; it all feels so reasonable to me. Like, if The Matrix was a guy, he’d be the type of guy who calls The Boondock Saints his favorite movie, you know what I mean? The kind who’d smoke salvia he bought at gas stations. The kind to get catalogs for swords in the mail. A tryhard dork, in other words, someone self-consciously “edgy.” And yet people seem to love this guy!

From my vantage point, it seems the most conventional position is that the original Matrix film is a pop culture masterpiece, while the sequels were disappointing or awful. There’s another subset of fans that thinks Reloaded is actually very strong and unjustly derided due to its proximity to Revolutions, which is legitimately bad. And then of course there is the fringe that insists they’re all amazing. But it doesn’t seem like many people question the classic status of the first. It’s canon, part of the crazy-fertile 1999 movie boom. Its influence on visual effects, fight scene choreography, and how action is shot is legendary, and this influence spilled over into changing the basic visual architecture of video games. Most everybody I know loves it, and it really is the film that the Wachowski sisters hang their reputation on. (I know Speed Racer has its defenders, but I think you’ve gotta call this a disappointing filmography, 20 years later.) Certainly there have been few movies that more effectively defined a particular moment in culture, giving the audience something they didn’t know they were missing. I don’t begrudge The Matrix its status as a cultural touchstone.

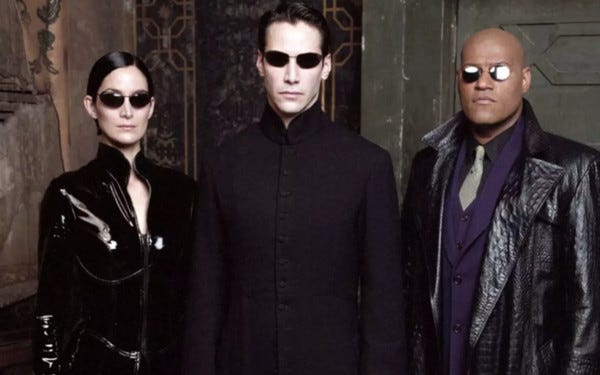

But it’s just so… bad. Embarrassingly bad. Everything about it seems calculated to be maximally adolescent, which is fine if we’re talking about the latest sequel to The Kissing Booth but less attractive when we’re talking about an R-rated blockbuster that is just bursting with deep things it wants to say. Many people will concede that the series is all about style over substance, making it harder to swallow that no one wants to admit how fucking dumb the style looks. The movie part of the movie is bad; the legendary aesthetics are even worse. Look at these fuckers:

If these three walked by me I’d point them to the nearest vampire rave, or perhaps try to buy some molly off of them. I know Hot Topic is a clichéd reference in this context but, honestly, where else would these people shop? I guess the Etsy stores that are frequented by anxious 47-year-old women who have recently rebranded as witches. Everything about the movie’s look seemed dated to me the very day I went to the theater. Doesn’t this look like some 11-year-old’s vision of what cool people look like? You’re indoors! Take your sunglasses off! Who walks around in all-black, all-leather everything? Can you imagine how they must smell on a warm day? I get that some people now call this all deliberately over-the-top, say that it’s poking fun at itself, insist that it’s supposed to look a little ridiculous. But I don’t think I got any sense that the visual style was supposed to be silly as a 17 year old, or in the half-dozen times I’ve seen it in the past 20 years, nor from watching it again recently. The way it’s shot and framed and presented all suggests that the movie and its makers think it all looks really, sincerely cool. Why did Morpheus steal the Joker’s suit?

It doesn’t help that the movie’s most aped and parodied invention, bullet time, doesn’t really thrill me. I don’t have a good reason why not, it just doesn’t hit me where it should. Yes, you can have Carrie Anne Moss do a jump kick, then spin the camera around her as she hangs in the air before kicking somebody in the face, but… why? To me, these diversions just create a disconnect between action and reaction that dulls their impact. Or perhaps watching bullet time become a cliché across my adult life has dulled whatever initial thrill I may have felt back in the Clinton administration, and this movie is a victim of its own influence. One way or another, the visual thrills, while impressively conceived and executed, don’t hit me with any of the force of movies like The Raid or Attack the Block - high standards, I know, but we’re talking about an action classic, one with a reputation as a high water mark of spectacle.

The problem with the defense that the film is intentionally ridiculous, visually or in general, is that it takes itself so immensely seriously. When Neo walks into the police station in semi-slow motion with his black duster and his cool sunglasses, there isn’t a hint of irony onscreen. I think people read in some tongue-in-cheek elements that aren’t there due to nostalgia goggles. Remember, this was an earlier era of big-deal moviemaking; this was before the people who make the Fast & Furious movies showed every other filmmaker how to control the narrative by making sure everyone knows that you’re in on the joke. (Which drained those movies of all of their organic joy and led to the cynicism of the MCU, but anyway.) Nor do I think that the movie’s biggest fans would want it to be rescued by saying that it was all meant to be kind of a joke. I suspect that its sincerity and lack of guile are part of why people love it.

Besides, there’s too many issues of great import going on for it to all be a joke. The Matrix’s philosophical pretensions just don’t mesh well with the notion that it’s all a lighthearted romp that no one’s taking too seriously. The movie’s constantly diverting our attention towards a freshman year philosophy seminar. Someone’s always dropping a line from Spinoza or whatever when there’s a pause in the action.

It doesn’t help that those pretensions mostly amount to gibberish. I’ve heard it said that, in light of both Wachowski sisters coming out as trans, The Matrix looks like a very obvious fable about transitioning. That may be so, and it’s interesting to think about. But I don’t think that reading changes the confusion of an immense amount of ideas getting thrown around in this series for what appears to be no coherent effect - causality, control, free will and the illusion of same, Buddhism, the occult. Into the Big Idea Blender they all go. I like heady action movies! I like blockbuster filmmaking that wants to explore big ideas. But at some point you actually have to say something. What is the position on free will of The Matrix trilogy? I have no idea. On causality? I have no idea. What’s the core theme of the first movie? “Ignorance isn’t actually bliss”? It’s all a mess, a muddled collection of deepities that are broken up by action sequences that vary between those that are visceral and affecting and those that are kind of floaty and consequence-less. (When Neo unloads a goddamn minigun into a room where Morpheus is sitting right in the middle, as part of an effort to save Morpheus, I just… what?) I don’t know. This might just be down to the mysteries of taste, but alternating between Zen kōans that go nowhere and frenetic violence isn’t my speed.

I don’t want to stray too far from the first movie here, but the infamous Architect scene in Reloaded really speaks to my issue with this whole franchise. Many people have complained that the scene is long and boring. And it is both long and boring! But what really gets to me is that he never actually says anything, that this incredibly dragged-out meeting between our protagonist and an intelligence that knows many important secrets takes place and yet at the end I’m no closer to understanding either the plot or the themes. “Shit is complicated” is the closest I get in either domain, lessons about the story and its world or the broader moral of the movie. And though that particular character and scene exemplify this problem, the original movie is guilty of it too - including a lot of handwavy talk about the setting and about the deeper philosophical issues the movie begs us to consider. This problem is exacerbated by the script’s dedication to expressing itself in clever little aphorisms. I kind of understand what Baudrillard means by “the desert of the real” in the essay in which he coined it, but I just don’t grasp why Morpheus would say that particular thing at that point in time, other than that it sounds cool.

And if it’s just to sound cool, fine! But if that’s what we’re going for, stop dressing everything up. Better to be clever about being stupid than stupid about being clever. If anything, the film has almost too much dedication to being actually deep rather than action movie deep, to its detriment. Take the infamous red or blue pill scene. Setting aside how that imagery has been appropriated into online culture, it puts forward a very deliberate representation of choice and free will. Neo and Neo alone must choose. OK. This echoes the choice Agent Smith gives him in the interrogation room. But then the movie goes out of its way to show that Neo doesn’t actually have a choice at all, that he was bound to end up as the One no matter what he did. This could be seen in the fact that he chooses (or “chooses”) to follow the white rabbit, but does so only after an explicit command from an entity he knows nothing about, or even more when he breaks the vase because the Oracle forgave him for being about to do so. Also OK. What’s not OK is never arriving at any coherent sense of how free will and fate interact, posing questions without proffering any answers. Agent Smith repeatedly refers to himself and his larger collective as inevitable, and the resistance against them is posed in terms of agency, suggesting that no, we do control our fate, or we should fight to do so, at any rate? But the Architect knows everything, suggesting the future is predetermined, but also so does the Oracle who opposes him. And Morpheus, when convenient, knows everything. I think.

The Oracle when she said that Morpheus was going to die, and Neo saved him, so we have free will! But Morpheus says she told him exactly what he needed to hear, suggesting she manipulated him and he had no agency. But then isn’t Agent Smith right? I am le confuse. Also, I know the movie cares about these questions because Morpheus literally says “Do you believe in fate?” to Neo, which is part of its larger habit of just telling you what’s on its mind. That would just be clumsy, except that (again) it doesn’t know what’s on its mind, not really, so the tic is even more obvious. Do you believe in fate, movie? Wachowskis? I sat through like 7 hours of this stuff and never found out.

But then a rack of guns comes out from nowhere, and it goes whooooosh!

Look, I want to like all of this more than I do. I too just want to lay back and enjoy a bravura and kitschy triumph of aesthetics that articulates several different kinds of pre-millennium tension. I want to enjoy the guns and the Czech raver clothes and the (pre-Crouching Tiger) balletic martial arts. But for whatever reason it just never congeals; the style is too ridiculous and the substance is too confused. Perhaps what colors this for me is that there’s another 90s movie that I think pulls off the aesthetics and the action The Matrix is going for, with precisely the goofy spirit people say they like and without the go-nowhere brain teasers - Blade. The Blade trilogy, which started a year earlier, pulls off the ridiculous(ly cool) black leather and shades look with more panache than The Matrix, and it did so without posing existential riddles it didn’t want to solve or crawling too far up its own ass. And watching Blade today is a pleasure because, in contrast with the previously-mentioned Fast franchise, the movie doesn’t constantly let you know that it’s winking along with you. It premiered before this awful Age of Knowingness, and so did The Matrix, which in hindsight I think is the thing I like the most about it.

Oh well. At least “I know kung fu” is cool.

Update: Ross Douthat with a j’accuse!

I enjoyed The Matrix as a kid, never watched the sequels, and have not rewatched The Matrix since then, so I have no strong opinion on it. But I do want to defend, in abstract, the idea of a movie having themes without clear takeaways.

I think it's okay for a movie (or any work of art) to explore a theme without necessarily having a single, specific thing to say about that theme. In fact, I think this is a mature approach to theme in a story. It therefore doesn't necessarily seem muddled to me that The Matrix might have different characters expressing conflicting perspectives on free will - the point might just be to have a discussion on it, not express a canonical statement on what free will is, or whether it's something we possess.

The remedial philosophy and garbled religious messages I can deal with, but having just rewatched it recently, I think the Matrix's plot stumbles on a much more elementary level: the conflict is all wrong. The machines are so obviously, overwhelmingly evil that they don't really have any kind of characterization or motive beyond "humans bad, machines good."

I honestly think there's a much sharper, more provocative version of the Matrix where Cypher (the snitch/traitor) gets more attention, more sympathy, and a more central role in the story. As it stands, his betrayal is mostly there to move the plot into Act III, but I find his choice far more fascinating than any of the Messiah stuff. Given how shitty the "real" world turns out to be, how many people would really, truly choose to unplug from the Matrix? What is the value of reality? Can a meaningful life be lived in the simulation? Is unplugging people an ethical harm?

This meshes a lot better with the movie's ostensible themes of reality, illusion, choice, and human dignity than the messy, overlong kung-fu in fetish gear fight scenes that we get. The most interesting problems posed by the Matrix are the ones you can't punch away.