I miss taking drugs the way I miss an old girlfriend. I'll go weeks, months, without thinking about them, and then there will be some stimulus - some action, some sensation, a smell, a song - and old patterns and habits slip over me and put me back in that mindset. And after that it will be a persistent, nagging longing. I will find myself absently missing something, unsure of what it is, exactly, until I realize how long it's been since I got high, high with friends. I want it like I want an old hooded sweatshirt that wore better than anything else I ever owned.

I miss taking drugs with the kind of bittersweet nostalgia where you eventually have to say, "no, no more remembering, not for a while," because it's so insistent and so seductively sad that you feel like you could get pulled down into it forever. It was a passionate love affair and like most it feels now that it was far too short, though really it went on for years and we stopped only gradually and in fits. I say we because we were a we, then, and we still are, but not as much, and perhaps that too is what I'm mourning. (But the drugs, too. Not just as a proxy. Not just as a way to access that closeness. The drugs, too, were the thing.) "We" is important: we took them together. They say it's the social thing that will kill you and perhaps that's true, but it's also the social thing that is most alive inside of you. It's the commitment to all going up and inward and back down together. It's joining with each other in a pursuit that society at large insists on defining as ugly and dangerous and untoward, and knowing that together it can be (can be) beautiful and safe and totally, wonderfully proper. In the pushing of that limit together - in the absolute and unapologetic choosing of the shared small-group values over the values of the larger world - there is a commitment that approaches family.

When I am missing drugs I never romanticize them. In fact part of what I celebrate is exactly the parts I enjoyed least. It’s important to remember them, for clarity and for truth, and to keep the experiences real, rather than a sunny lie. What I refuse to do is to remember them with some sort of commitment to "showing both sides," the way a screenwriter who writes a movie about taking drugs insists on scenes where the oh-so-terrible consequences are shown, for balance, or worse, for maturity. I loved drugs in part because the consequences were so minor and because there was never any movie-of-the-week tragedy.

But, yes, I remember lying on a strangers couch, coked-up heart going like mad, scared that it would never slow down. I remember sitting in the passenger seat while a friend got pulled over for speeding with a quarter pound of high-quality marijuana in the back. I remember the way waiters at diners could look at you, knowing, and wither you with a glance, a look that contained all of the societal disapproval that you could consciously reject but never really shake. I remember the bad trips. I remember the precise moments in the car rides home where you realized that whatever drug your crew has recently been enjoying has suddenly and irrevocably lost that magic. I remember the sudden jags of panic that, maybe, the old D.A.R.E. officers were right, right about everything, and that you were just some sad junkie stereotype.

Yet for all of it, what consequence? Perhaps, occasionally, haze at the limits of memory. Many thousands of dollars spent (though not poorly). Some embarrassing true stories you just can't shake. Those few square old friends who read too many magazines and decided, publicly and loudly, to turn away from us, because we had become the wrong sort. Other than that, the only thing that remains is this - this nostalgia, this endless wistfulness for the times when you were almost impolitely alive, this feeling that is bittersweet, bittersweet, bittersweet. And this, you wouldn't trade for anything. Not if you went through it. Not if you spent rough nights wandering the soft places of your consciousness, compelled by physical thrill and manic with youth, and promised to yourself that if you ever found your way out of whatever maze of hallucinations you were in, you would walk out confidently, unapologetic at the night you had enjoyed, totally spent, and singing. You experience no permanent consequences because you refuse the crass narrative that there must be consequences.

Not that there wasn't recovery. Recovery was a part of it; recovery was necessary. Recovery was the deep justice of the brutal communal hangover, and don't kid yourself about our national drug of choice. Recovery was the two or three days of little responsibility you needed after taking acid. (Not that you couldn't function but that you didn't want to, that part of the lesson was in the harsh sober spottiness as you contemplated both the trip and the comedown.) Recovery was not taking ecstasy for half a year after taking it every weekend for months, as your synapses built themselves back up so that you could again experience flooding your nervous system with serotonin. Recovery was a semester of pure sobriety, a summer of no drinking, giving up smoking weed for a while to clear out the cobwebs. The purely unaltered mind became in context its own kind of enjoyable trip.

I liked doing what I knew others wanted to do but didn't dare try. I liked the exhilaration. I liked the way some rare drug might suddenly become available, unexpectedly, and the pleasure of such a surprise. I liked the delight and terror of an acid comeback, days later. I liked to meet other people who liked to get high but who were ordinarily afraid to admit it, and seeing the relief on their faces as they realized that, with us, there was no hiding and no pretense. I liked the candor with which our group talked about drugs - to friends, to strangers, and in the early days, to parents. I liked telling a cop, "I'm high right now, but I don't have anything on me." I liked the way that the experience of being high made cliché and banal metaphors vibrant and true. Somehow, language was at once too feeble to express the power of what we were experiencing and yet at the same time language was empowered by the experience, the innumerable slang terms elevated to poetry by the drugs: getting blunted, burning up, going sideways, rolling, flying. Even the metaphor that is "getting high" - so tired a term, so perfectly accurate.

I liked the way that, when high, I was sure I was awash in unmediated, unadulterated experience. I liked how that was one of the few times in my life when I felt that I was receiving it raw and untranslated, not watching a movie of my life, or gazing out at it through the screen of a window. I liked how it was not received through the endless array of technological intermediaries my life is now surrounded by - life lived through a cell phone, through Facebook, through a digital camera. When high, the ineffable but unmistakable effects of brain chemistry - serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine - removed the quotation marks from life, the layers of irony and predigested experience, and the cacophony of my own neurotic mind. Such experience was and is rare for me; I know it when I am having sex, when I feel genuine fear, when I access courage in the face of physical danger, and when I am in the grips of one of the manic episodes that threaten to ruin my life or end it. And I knew that feelin when I was high.

I miss the keen anticipatory contact highs of the hour before. I miss how that anticipation would be perfectly met, almost without fail, by the onset of the real high. I miss the feeling of the pills in my pocket. I miss the head bobbing-- always with the head bobbing. I miss the moment when you see one of your friends, in the unguarded moment of the peak of her high, slowly close her eyes, roll her head back towards the ceiling, and exalt. I miss the wired, edgy wakefulness of visiting a dealer you don't really know. I miss the terrible musty taste of psychedelic mushrooms, and the peanut butter you ate with them, despite its total ineffectiveness to cover that taste. I miss how being on drugs could somehow alter your style without changing your clothes, the way your whole fashion would change with just the application of a little chemical engineering - a different look, a different walk, a different confidence. I miss the way you were sure that no friends could ever mean as much as yours did to you at that moment. I miss coming down and feeling just that same way, stone sober. I miss the sly glances out of the corners of the eye at each other, reminding each other that, at that moment, nobody else knew what you and your crew knew. I miss the handholding. I miss a half dozen bodies passed out on the same bed and two dozen in an apartment the size of a parking space. I miss the tenderness.

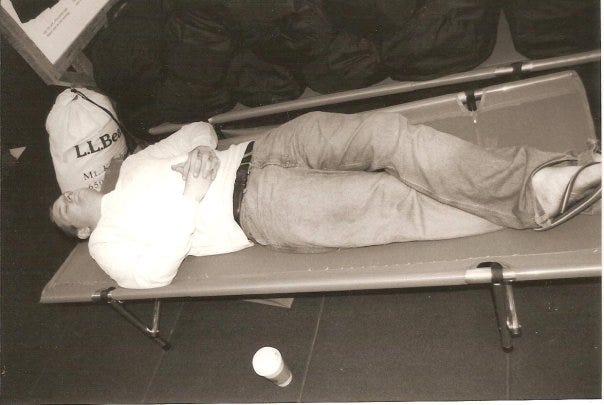

And god, I miss the mornings after. I miss the perfection of the grogginess. I miss the unidentifiable aches. I miss pulling the blanket up in polite refusal of the morning. I miss glancing over at your friend and smiling that shared secret knowing smile. I miss those two morning beers that perfectly eased the hangover. I miss watching daytime television with bemusement but almost manic attention. I miss greasy bacon and eggs in a body that had consumed nothing but water and cigarettes and opium for the twelve previous hours. I miss looking at your friends, hair all crazy, disheveled past credulity, and perfect. I miss sitting in a sunlit room in a beautiful city on a beautiful day, smoking weed and slowly gathering strength for the night to come. I miss the unbearable warmth of it all.

I miss all of it, and I likely will for the rest of my life.

This is not a conversion narrative. This is not a confession. This is not a debriefing or a postmortem. This is certainly not an apology. It is not advocacy. It is neither encouragement nor warning. It offers no advice and it speaks no judgment. It is, perhaps, only an acknowledgment: this was us, and for some time there was this dangerous beauty in our lives, and today we take our danger and our beauty in different measures. It would be vulgar and wrong to say, after all this, that one has to stop. That is the way of the slick screenwriter, after all. There will be no folding of this story into the pleasing symmetries of “growing up.” These days I feel so much less grown up than I did back then.... I don't know that we had to stop. I don't know that anyone has to. I don't even know that it was right that we stopped, that we are safer, or healthier, or more responsible now for having stopped.

I only know that we did. Now, I confront life in the cold stare of something like sobriety, and I’m committed to it. Things are okay, for all of us. We are smart and we are strong and we have leaned on each other when sober living seems an absurd undertaking. The urge is less insistent now, and always the memories grow colder and more distant. And now when I mourn I mourn not only for what we used to do but for the way that I used to miss it, the churning ache within me, bittersweet, bittersweet, lying on the bed, thinking of those times. It's behind me, now. It's behind us. Ahead lies, perhaps, happiness or its equivalents. We are still an us. Perhaps we are a little less of an us now. I don't know what this has all meant for me, or what this statement means. I don't know what is going to happen. I only know that there was a time when, in the furious beauty of our youth, there was something within us, and for a while it burned like fire.

Oh, man, this is exactly how I feel about quitting cigarettes. I even use the same line, that I miss them like I miss an ex-girlfriend. Smoking was such an integral part of my day for so long, for good and ill. I would never start up again, but I don't regret starting. If I were a teen today I probably wouldn't because it's so much more expensive and restricted (I once smoked on an airplane!) But I don't regret it, and I think back on that time wistfully.

That's always the advice I give people who are trying to quit, to treat it like being dumped. Don't tell yourself it's bad because you know that's not true. Just tell yourself that period of your life is over and it's time to move on.

Absolutely beautiful writing.