How to Quit Substack

a guide for the righteous

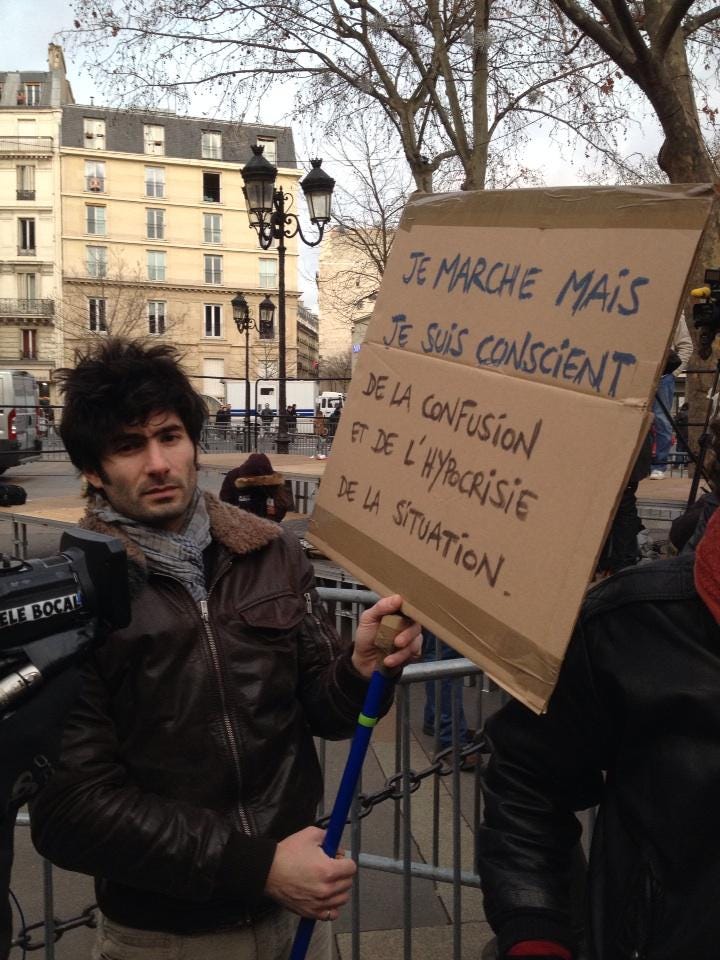

I don’t know the name of the man in this photo, don’t know anything about him at all. He might stand against everything I believe in, I have no idea. But he’s been a political hero of mine for almost exactly 9 nine years. He was photographed headed to the protest following the Charlie Hebdo attack. His sign reads, “I’m marching, but I’m aware of the hypocrisy and confusion of the situation.” Which is, I think, a very good tool to have in your belt - the clarity and courage to say that you think the particular action you’re taking is probably the right one, but that you know your motives are impure, your thinking muddled, and your targets unclear. When you admit to ethical confusion, you allow your ethical claims to live in the same sad space of qualification and uncertainty that we all do, and this in turns makes you more human and the claims more serious. It doesn’t, however, do much for marketing. I wish more people had access to that kind of space; I wish I could access it more often myself. And I certainly wish the people quitting Substack so loudly and ostentatiously did. They might find that these big moral spectacles are long on spectacle and short on morality. Ultimately only they can ask themselves what they’re really up to and whose interests, exactly, it all serves.

In socialist circles, you will often hear that “there’s no ethical living under capitalism.” You see, when you’ve indicted the whole capitalist system, people will often say things like “those shoes you’re wearing were made in a factory where the workers are exploited, how can you call yourself a socialist?” To which we say, there is no ethnical living under capitalism, there are no consumer choices that we could make that would remove us from complicity in exploitation, all any of us can do is to work like hell for a better system. The saying can certainly be taken too far at times, used as a blanket excuse not to think about what you buy or do. But it’s also a very important principle, a statement of the permanent moral ambiguity in which we’re trapped and a lesson about the limits of our ethical pretensions. We can’t get too high on our own righteousness because everywhere we look we are entangled in immoral systems and contribute to suffering. And to be clear, that statement is not exculpatory; rather, it reminds us that we are all implicated. If you tell me that it’s bad to own a Tesla because it enriches Elon Musk, I might point out that you eat pineapples that were picked by a company that murders union organizers in central America, and I would have a point. “No ethical living under capitalism” does not exonerate, it indicts, in a way that paradoxically creates the space for us to live in a messy world. We’re all hypocrites either way. Some of us remain aware of that fact and some of us don’t.

The Atlantic has, somehow, published yet-another anti-Subtack hit job, this time written by someone called Jacob Stern. (His LinkedIn proudly notes that he is a graduate of the $50k/year Georgetown Day School, which I would like to make fun of but reluctantly find kind of endearing.) The piece’s existence is both very difficult and very easy to understand. Difficult, because it adds nothing to what Jonathan M. Katz ’s self-regarding piece on the same topic in the same magazine did a couple weeks ago, really nothing at all; easy, because declaring people working without the blessings of big deal media to be racists is the kind of scutwork on which careers are now built. Leadership at The Atlantic see Substack as an ox to be gored, and you can earn a lot of chits in this business being that kind of bagman. I hope someday you get to write the piece of your dreams, Jacob. Try not to crawl over too many bodies on the way there, if you can.

The most Stern has to offer here is a little bit of football-spiking, in the form of talking about how tech guy Casey Newton and professional very clever boy Ryan Broderick have left the platform. What Stern has conspicuously failed to do is to actually explain the basic rules that I previously asked for, the simple and coherent reason why Substack is damned by problems that are native to literally all platforms, over time. I am waiting for someone to make a minimally-compelling argument for why using Substack is worse than using Wordpress, or DNS routing, or the TCP/IP protocol. Sterns links to Newton and Broderick’s peacocking farewells, but they provide no clarity either. And I have to be the one to point out that none of them, not Katz or Stern or Broderick or Newton or any of the many people who have contributed to this grubby little genre, have ever been able to articulate the core moral superiority of their future platforms that house far-right extremists compared to that of the one they’re so proud to leave.

Broderick’s “I’m leaving the Nazi place” piece is self-congratulatory even in context with the rest of this genre, which is an achievement. It also demonstrates the fundamental paucity of sense at the heart of all of this. Substack’s critics are compelled by basic factual reality to acknowledge that essentially no platforms or services are free from the presence of far-right content, but to do the sales job they want to do and stay committed to the bit, they have to cobble together some sort of plausible justification. They appear to have arrived at the idea that what makes Substack bad is not what it hosts (which obliterates the many references to their Terms of Service, but never mind) but what it promotes. I think. Broderick says, with the kind of zeal that inevitably suggests moral confusion,

None of this had to happen. Ghost, a Substack competitor, has almost no real moderation to speak of, but no one seems to care. You know why? Because it’s not trying to jam all of its users into one feed to compete with Twitter or whatever.

I was expecting to not be impressed by this part, but I’m still surprised by how weak this is as a bit of moral reasoning. It’s particularly amusing given that Broderick is still an avid user of actual Twitter, which is stuffed to the gills with Nazis that are promoted using its discovery tools. His use of that site puts money into the pocket of Elon Musk and suborns “X”’s continued existence as a hub for exactly the kind of far-right content he is so desperate to not be associated with. He appears to find no contradictions there.

But OK - why is it that the discovery tools are the bad part, exactly? Is the problem the existence of Nazis, Ryan? Or that you don’t want to be all jammed up with them? For one thing, I have bad news for you: you get all jammed up with people with despicable beliefs every time you stand in line at the supermarket. Broderick’s complaint is about a fundamental problem of the world, but bent by convenience to be about a particular service, run by a particular company, one associated with a particular place in our world thanks to the dogged antipathy of media people who agreed to live in New York on $50,000 a year under the theory that doing so meant they would be invited to some groovy parties, which they found to their chagrin were shut down years ago. That is the anger that powers all of this. Not antipathy to Nazis. But OK, set that aside: for this to make any sense, you would have to be able to prove (as in, with evidence) that Substack’s discovery tools have actually, actively been promoting this small handful of objectionable newsletters. Katz’s article waves at that, but does nothing to prove it; Newton’s post suggests it, but provides no evidence that it’s true; Stern’s essay assumes it, but seems entirely indifferent to demonstrating it. This is how the Village operates when it wants to advance a particular claim: someone from within that social hierarchy says that it’s true without evidence, a bunch of other people repeat it without providing said evidence, and because it is convenient, their peers mutually agree to believe that it’s true. Like I said, for Stern, this is professionally-convenient scutwork.

The very reason Ghost was created was to make the kind of moderation Broderick wants impossible, and yet Broderick has jerry-rigged a moral schema that indicts Substack and excuses Ghost. This is, speaking generously, an argument of convenience built on a foundation of idiocy.

As I said, Casey Netwon’s post makes something similar of an argument, and I find it similarly confused. Substack’s discovery tools help push people towards Bad Things and, supposedly, puts money in the hands of Bad People. They keep trotting some version of this out there, and I keep turning it over like a well-worn quarter, and I keep failing to find the barest hint of sense in it. I swear to you that I’m trying to be generous here. The claim is that the problem with hosting “Nazi content” is only bad because of the discovery tools. But people take to Facebook and Twitter and Reddit and Discord and Wordpress to share their Nazi propaganda all the time. Can that make those platforms similarly Bad? If it’s the sharing and not the hosting, does Ghost become bad if someone sets up an automated Twitter feed of Nazi Ghost posts? What are the rules? I don’t know; all of this stuff lives in a permanent state of confusion, despite all the posturing and sanctimony. Katz’s piece says that the hosted content itself is bad, that giving Nazis a place to share their ideas is bad, and by extension that the rest of us having to exist in the world alongside of people who endorse these ideas is bad. The latter is true, but of course as I keep saying that fact preceded Substack and will outlive us all. The Nazi content that Katz found (and reported on with sufficient inaccuracy that The Atlantic had to issue a correction) is an absolutely tiny portion of Substack, and no one has demonstrated that any of it was getting surfaced thanks to Substack’s discovery tools, at all, ever. But even if it was, why is it the discovery tools that are disqualifying? What is the fundamental moral principle here?

Amusingly, the whole “it’s not the hosting, it’s the surfacing” line is functionally identical to Musk’s much-mocked “freedom of speech, not freedom of reach” line.

No, I think what’s happening here is pretty simple. Broderick, and Newton, and the sublimely self-righteous Rusty Foster, and others like them are creatures of the media professional-social human centipede that I’ve criticized for so long. They are firmly ensconced in the status hierarchies and petty frenemy networks that define that space. Like most people in media, I imagine, they’re feeling a little lost over the demise of media Twitter thanks to Elon Musk’s whims, given that it was the organizing force that did so much to define the culture of the industry and which handed out the social rewards that have had to replace the financial rewards that no longer exist. These guys are feeling pretty shitty about their industry and its economics and the fact that Media High School appears to no longer be in session. They’d like to goose subscriptions and they’d like to do so in a way that burnishes their credentials as good guys who really care. They look around and notice that the kind of people who write overwrought essays for The Cut about how the latest Billie Eilish album destroyed patriarchy or whatever are not fond of Substack, principally because a lot of us make more on Substack in a month than they make in a year writing overwrought essays for The Cut. And these good white men say, aha! Market opportunity! And that’s why they leave. That’s 90% of what you need to understand.

Here’s the thing: you can just fucking say that. “People in my professional and social circles don’t like Substack, and I care too much about what they think, so I’m switching to a different service.” Cool. Go for it. “My subscribers are mostly the kind of muddled liberals who boast about the moral superiority of their electric Hyundai, which was built with minerals mined by literal child slaves, and they don’t like Substack for reasons arising from that same basic confusion.” Understood. Get that bread, honey. But please be real with me. Newton in particular is savvy enough to know what he’s doing and why. Please, spare me from the self-fellating theatrics about how you’re too pure of a soul to sully your hands in the waters of Substack, which is just the internet. (I’ve got news for you boys: it’s all the internet! It’s all interconnected. That was the deal you signed up for the first time you used a broadband connection.) “My newsletter is a business, and I’m leaving Substack as a business decision.” There. That’s all you have to do.

But that doesn’t get pussyhat liberals shilling your wares for you on Mark “Genocide in Myanmar” Zuckerberg’s Threads by Facebook, does it now?

Let’s talk about Jeffrey Goldberg, editor in chief of The Atlantic, Stern’s boss, and the boss of whoever decided to publish Jonathan Katz.

Goldberg is a bad person. He was an actual prison camp guard at a notoriously abusive Israeli facility. In his book, Prisoners - you see, it’s not just a literal reference to the prison camp, it’s a clever metaphor for the Israel-Palestine conflict, cut the advance check! - in that book, he repeatedly dismisses and excuses and provides cover for techniques deployed on Palestinian prisoners that were torture under any definition. Goldberg specifically details covering up physical abuse of prisoners to help a buddy. (You can read Norman Finkelstein treat Goldberg exactly as he deserves here.) Worse, along with Judith Miller of The New York Times, Goldberg was the individual media member most responsible for getting us into war in Iraq. (I say “getting us into war in Iraq” and not “lying us into war in Iraq” because I really do believe Goldberg is gullible enough to have gotten rolled by such a blatant conman.) Miller’s career was destroyed, while Goldberg only continued failing up, probably because he’s a man. But in doing so much to make readers of the tony New Yorker comfortable with an invasion that would go on to kill at least a half million Iraqis, Goldberg stands as one of the single most despicable figures in the history of media. He is, objectively, a bigger villain than someone whose work you find a little fash-y.

You see that dead baby up there? Her blood is on Goldberg’s hands, in a very direct and uncomplicated way. You think it’s in poor taste to show her picture here? That’s cool. I think it was in poor taste of Jeffrey Goldberg to help kill her.

Perhaps you can anticipate my question, which I asked (to no answer at all) the last time I considered this stuff: why is being on a platform with a tiny handful of far-right extremists more disqualifying than directly working for a man who helped kill that baby and hundreds of thousands of more people? Seems like a good question. Seems like an obvious question. Seems like a question that maybe Katz, or Berg, should take seriously. If you write for the New York Times, you’re writing for a publication that beat the war drum as insistently, harshly, and angrily as any neocon rag you can imagine, and some of the people who worked there then still work there now. Why is it not an affront to the delicate morals of our political class to work there, exactly? American neo-Nazis are a pathetic fringe that only have as much power as the fear that they’re able to provoke, which liberals seem perversely dedicated to helping them with. The New York Times and The New Yorker are immensely influential institutions and they, along with the entire rest of the media, participated in generating bloodlust based on lies sufficient to push us into a ruinous war that ground children up like hamburger meat. Aside from Miller, it’s hard to think of a single person in media who paid any price at all. All of us who write for places that participated in that are dipping our hands in all that blood. My defense would be that there’s no ethical living under capitalism. I have mouths to feed. But I would understand that to be a statement made with a good deal of embarrassment and shame, not compatible with the kind of peacocking moral superiority I’m talking about here.

People write for places like The Atlantic despite the professional proximity to someone who actually, really got innocent people killed because it looks good on their resumes, and maybe if they write there they’ll end up somewhere with a decent 401(k) match. These are fundamentally financial decisions, which like most financial decisions are much more justifiable if they are discussed frankly in those terms. And that’s the thing: if you want to leave Substack, cool. Substack is a platform and a platform is a tool and a tool’s value is only its use. You are free to go, wherever you choose. But please, spare me the moral theatrics. Please. You still use Twitter despite the fact that you rub shoulders with Nazis (or “Nazis”) and enrich an awful man because you derive an unhealthy amount of your self-worth from that network and because you think it’s good business. There’s nothing wrong with selling your body, but please don’t call yourself a nun while you’re doing so. It’s vulgar; it cheapens us all.

Something called Matt Birchler has run like a dozen anti-Substack posts from his Ghost install recently. Do you think he’s doing that because of his spotless morals? Or because he’s found it’s a good way to farm subscriptions? This feels like an exciting new hustle in the online media space! Where are our media sleuths to talk about it as an underserved market space just calling out for more product? What say you, Casey Newton ? You’re such a keen observer of creator behavior; well, this whole “I’m leaving Substack” thing has become a sufficiently lucrative hustle that you’d expect a Platformer post about it. It would be right up their alley! And yet….

I will take the moral case for quitting Substack seriously the first time I see someone making it without wrapping it in an advertisement for their wares. I’ll take it seriously when they stop throwing it out there with a promo code for 20% off. I’ll take it seriously when it’s announced sheepishly, with uncertainty and unhappiness, by someone who knows that they live in a dark and lost world and that moving to Ghost or wherever the fuck is just a classic bit of human rationalization, the kind of ex-post-facto justification people come up with in pursuit of their own selfish interests. I’ll take it seriously when someone says “I’m leaving Substack, but I’m aware of the confusion and the hypocrisy of the situation.” Or, even better, “I’ve decided to switch platforms. I’ll be porting over your emails and credit card information next week. End of message.” Imagine that. Doesn’t get you a lot of likes and retweets though, does it? It’s kind of crazy to even contemplate, isn’t it? If you act with integrity but do so quietly, if you make a difficult choice and let it stay difficult, if you do the moral thing and no one’s around to celebrate you for it, did you ever really act at all?