How Convenient, That Kanye West's Behavior Could Not Possibly Be Influenced by His Mental Illness

how convenient

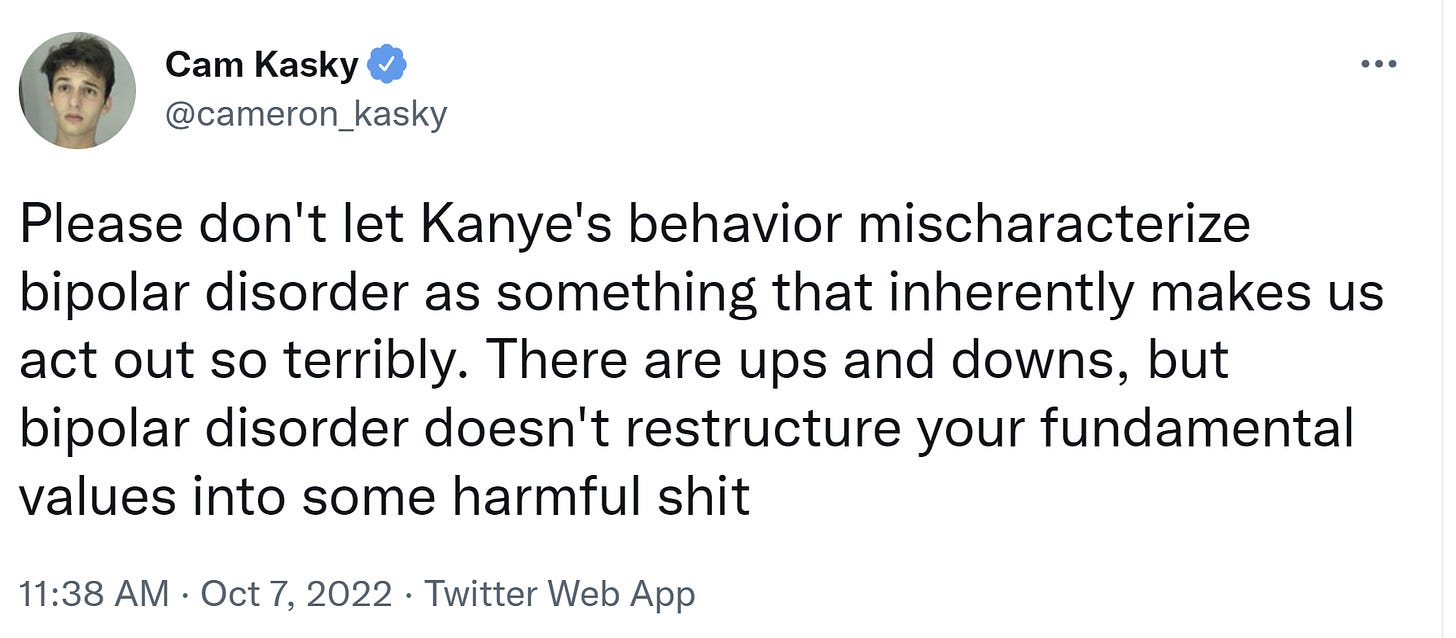

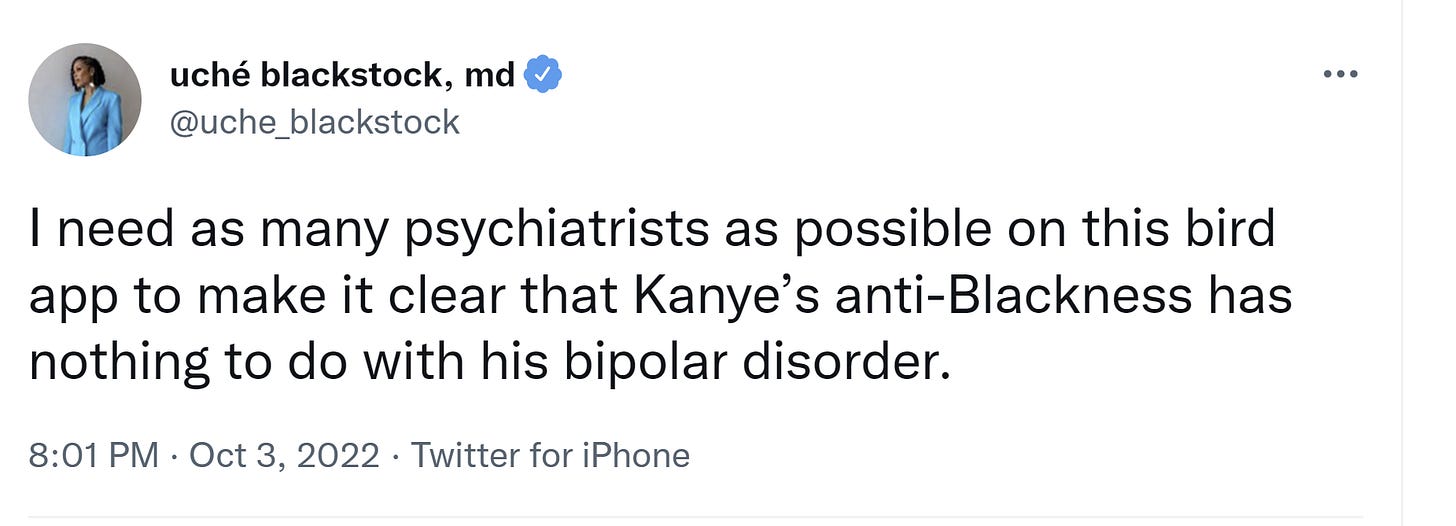

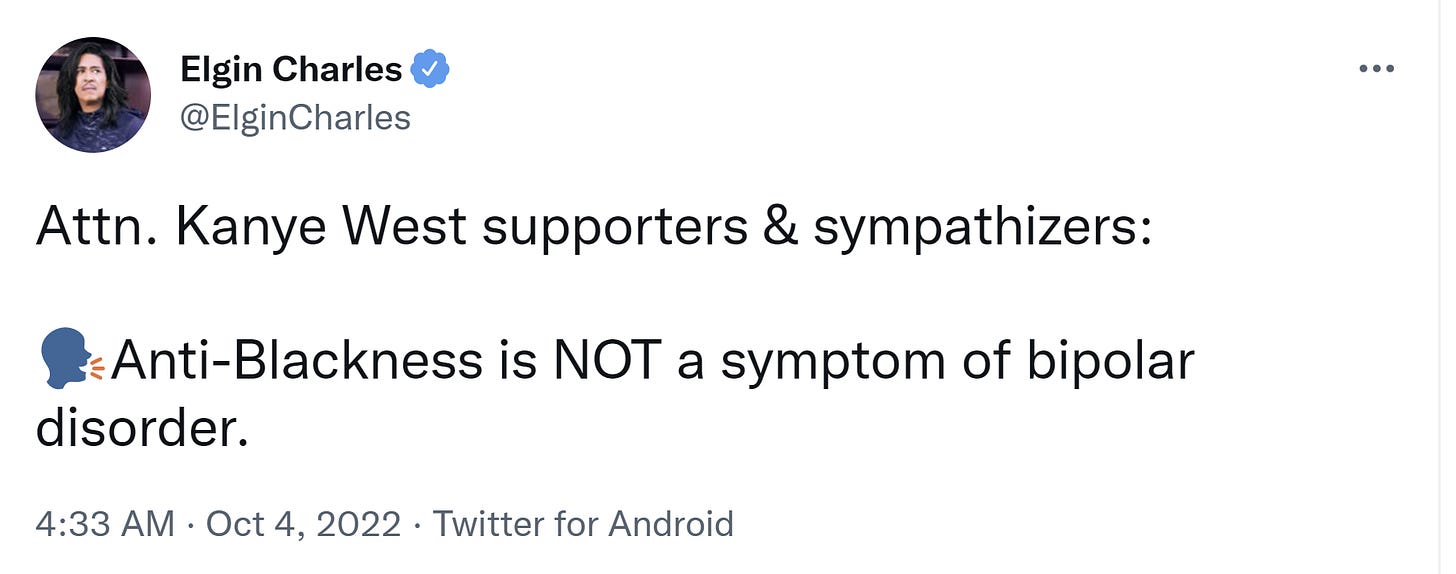

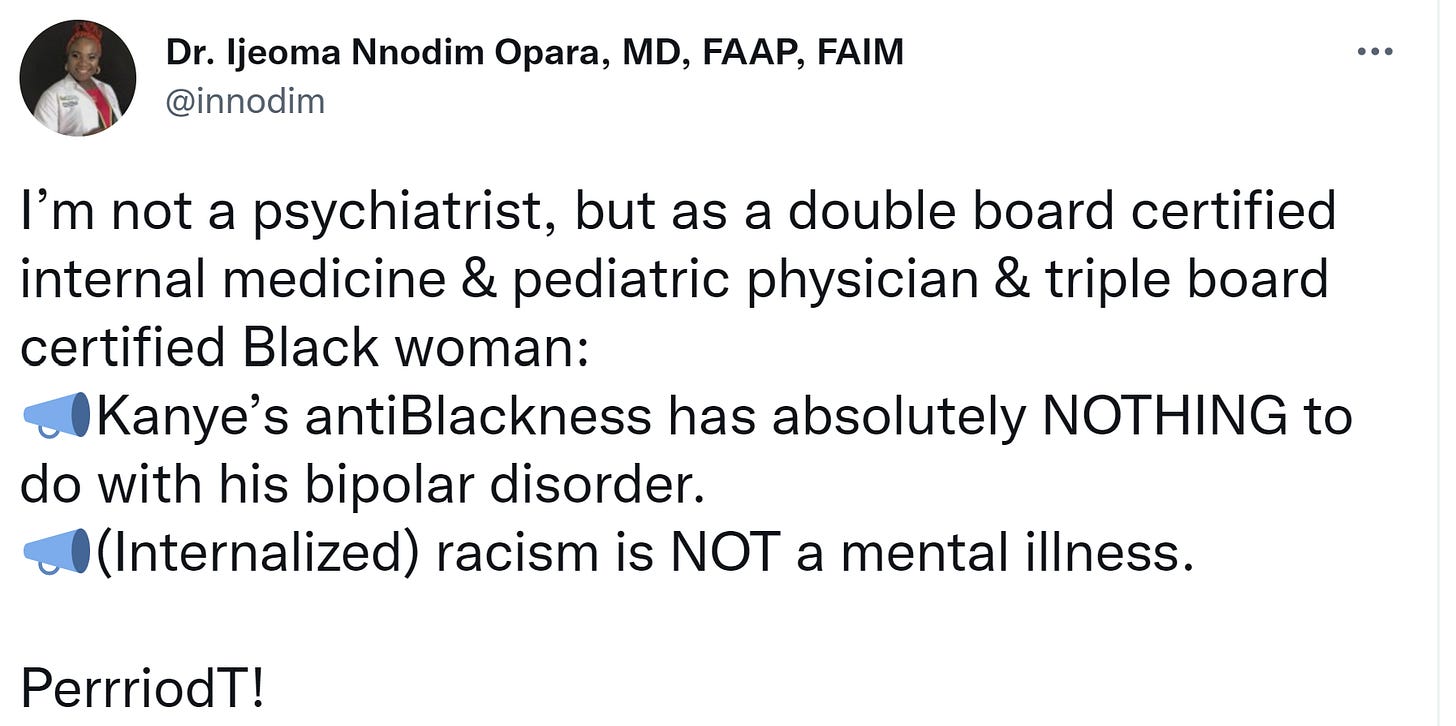

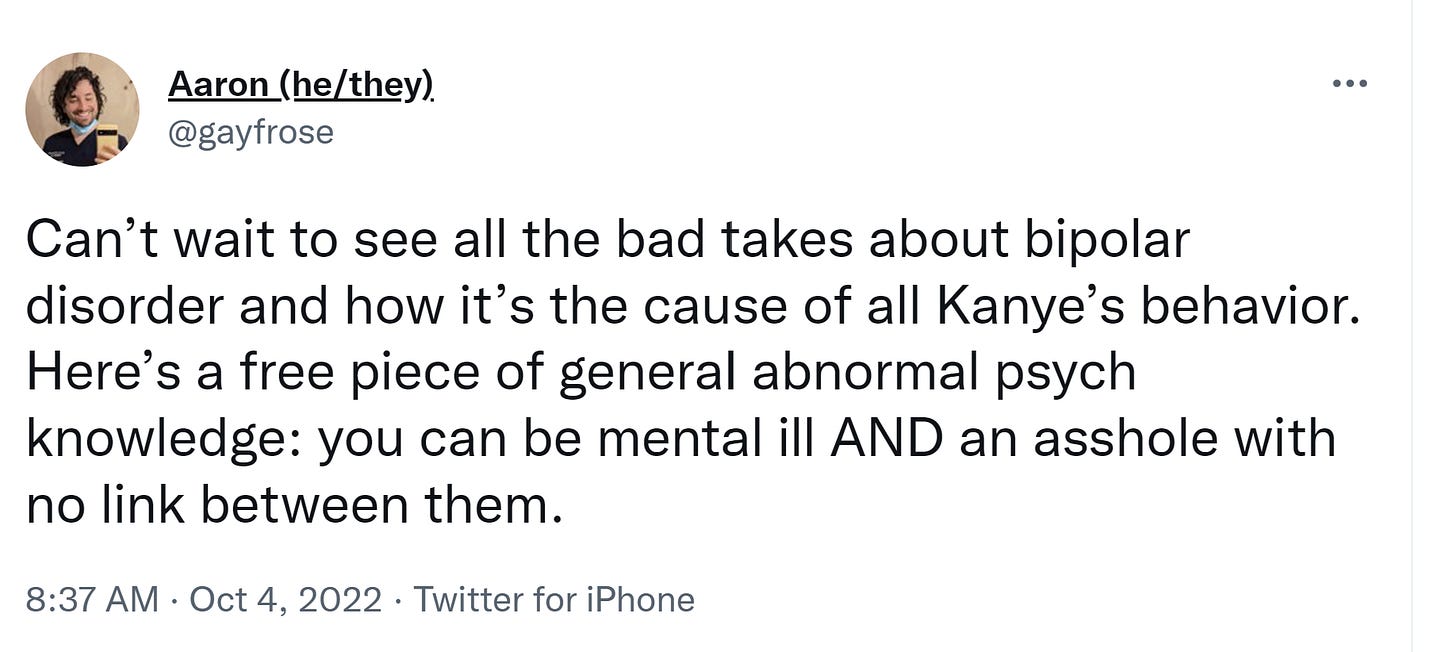

There’s a meme that’s arisen in the past few years, found prominently on social media: “mental illness doesn’t do that.” It’s a declaration that a given figure must not be given any special consideration, when weighing their behavior, due to their potential psychiatric disorders. The sociology of the term isn’t hard to understand. The stereotypical usage arises following a mass shooting. People want to reject right-wing claims that mental illness is to blame for such shootings, and they want to maintain the contemporary liberal conceit that race is the sole monocausal motivator of all events. Suggesting that mass shootings or other bad behavior could happen under the influence of psychiatric disorders complicates those questions, and we can’t have that. Now we have Kanye West, known to have bipolar disorder, who has been increasingly unstable, flirting with the right-wing, engaging in anti-Semitic tropes, and generally operating outside of the boundaries of what people imagine mental illness to look like when they define the mentally ill for political gain. He can’t be doing these things because he’s sick, according to many. He just can’t.

Because to consider the other possibility, that his serious mood disorder has indeed played some role in his tempestuous behavior, is to invite that which modern political culture can’t abide: moral complexity. In this era of social justice, everyone is divided between the perfectly unblemished victims and the permanently discarded oppressors. If West’s erratic behavior was influenced by his bipolar disorder, we might feel compelled to extend sympathy to someone who’s guilty of saying some unfortunate things; we would sully the perfect distinction between goodies and baddies. We would not be able to sit back in perfect judgment of West and comfortably assign him a place in our binary moral universe. We would be compelled to invite complication, equivocation, uncertainty. And we can’t have that. So we must insist that West’s bipolar disorder, a condition that can provoke extreme impulsivity and lower inhibitions, could not have played any role in his recent behavior. Like I said. Convenient.

In the background of this attitude lies the widespread, profoundly stupid assumption that to say that mental illness influences behavior is to necessarily fully exonerate someone from the moral or legal consequences of that behavior. Again, moral simplicity and binarism - the mentally ill are the disabled, the disabled are a protected minority group, and members of a protected minority group can do no wrong. But to say that West’s behavior might not be fully under his control is not to say that it’s not within his responsibility. I don’t think his bipolar disorder is fully and simplistically creating his unfortunate behaviors. Someone who commits a crime while psychotic still must face a legal accounting, after all, hopefully in a mental health facility instead of a jail. But I do think that West’s bipolar disorder complicates our relationship to those behaviors. It means that we can’t just assign full blame to him without taking his mindset into account. It means that we have to more thoroughly exercise our moral imagination. It means that we must speak and judge with greater reservation. It means that when we consider the social punishment that we might hand out, we must do so without the crutch of seeing West as entirely guilty or perfectly blameless. It means we must do things the hard way. It’s not convenient.

I was reading Martin Buber recently and have been thinking a lot about the moral challenge in the face of another, the moral challenge that arises simply from the presence of another person. I see that kind of challenge in West’s behavior. I don’t condone things he’s said and done recently. But there is a challenge we have to rise to in confronting those things. We have to do more and harder work to evaluate his behavior. We have to get our hands dirty. We have to be willing to both find that someone is guilty of bad things while bearing the complications of mental illness in mind. We have to be willing to arrive at conclusions that are not pleasing, that don’t sit well with us but that we feel compelled to embrace anyway. Precisely because it’s not easy. That’s the challenge in the face of another.

Two things I really hate: morals of convenience and false friends. The types of people who say “mental illness doesn’t do that” are the types to profess support for those with psychiatric disorders, but only when it’s easy, when the mentally ill are doing the socially approved things like talking to themselves on the subway. Which of course means that they are no friend to the mentally ill at all; support only means something when it comes at a cost. In its magisterial simplicity, social justice politics has created a vision of the mentally ill as unblemished and blameless children who are easy to exonerate because they never did anything wrong. But to spend time in a psychiatric facility is to hear the n-word, to meet people who have committed domestic violence, to confront the many forms of brokenness within the human race. It’s not cinematic. Nobody’s there who hasn’t done genuinely unfortunate things. That’s what mental illness actually is, not aesthetically-pleasing movie madness but grubby, dirty instability. I see a lot of it in West, and I hope he can get the help he seemingly resists. And I do blame him for his bad behavior at the same time. Balancing those things isn’t easy. Never is. You see, it’s complicated.