Following the Word

Recently I was taking my morning walk in Prospect Park when a stray gust of wind blew a pink quarter-page leaflet onto my chest. I pulled it off of my shirt and took a glance; a new carwash was advertising itself. The top script was in some gaudy “futuristic” font, which looked ridiculous on the wasted and forlorn leaflet, and thinking briefly about how that text came to be there, on that loose sheet of paper in a vast green park in a city drowned in advertisement, pushed by some lonely breeze through that place, on that day, and landing square in the sternum of this particular figure, a deeply frustrated writer buzzing with coffee, I suddenly apprehended that the existence of written words permitted time travel to and from and between all expressions of that form, not in a clichéd poster-at-the-library “reading is magic” way but in the literal sense of transporting my corporeal form along time’s arrow to reside somewhen else, to be there in those eras where old words were verdant and young, to feel them, physically, between my fingers, virginal and alive. So I traveled.

My body left this tired age behind, the leaflet fell in silence, and there I was careening down an ancient and vast wormhole, moving as fast as reading and as slow as writing. As I passed undistressed through the history of the fixed idea I took the time to admire the various works I saw, though they came in no order and with no inherent narrative logic. I passed The Tale of Genji, The Woman in White, and a dirty little limerick from a Thai bathroom stall. I reacquainted myself with a mildly amusing review of Jagged Little Pill I had read before in a doctor’s office in 1996. I slowed myself to admire a set of instructions for a portable sewing machine and tried not to look as I approached the ending of a novel I had not yet finished. I took notes about Flemish property deeds. I was entranced by box scores from Mets games printed in USA Today in the early 1980s. I took a certain sick pleasure in reading the most embarrassing text message you (yes, you) ever sent a love interest, and I paused to contemplate Tumblr fan fiction inspired by Nicholson Baker’s The Fermata, erotica based on erotica. I studied a receipt a Chinese tourist had received in an Atlantic City convenience store in 2006. I read my own obituary. I pawed loosely through records of crop yields that had been carefully detailed in cuneiform an indeterminate number of centuries ago in the lost city of Akkad. I stroked my chin while reading a piece from 2073 about how the AI takeover will be coming very soon. I read your diary. In an efficient bit of temporal plagiarism, I traveled through lost Amphibia’s emperies, waded through the sacred river Alph, explored the long barrows of Logres, and grew parched in deserts of vast eternity. And all of this was just the journey, just time spent in the wormhole.

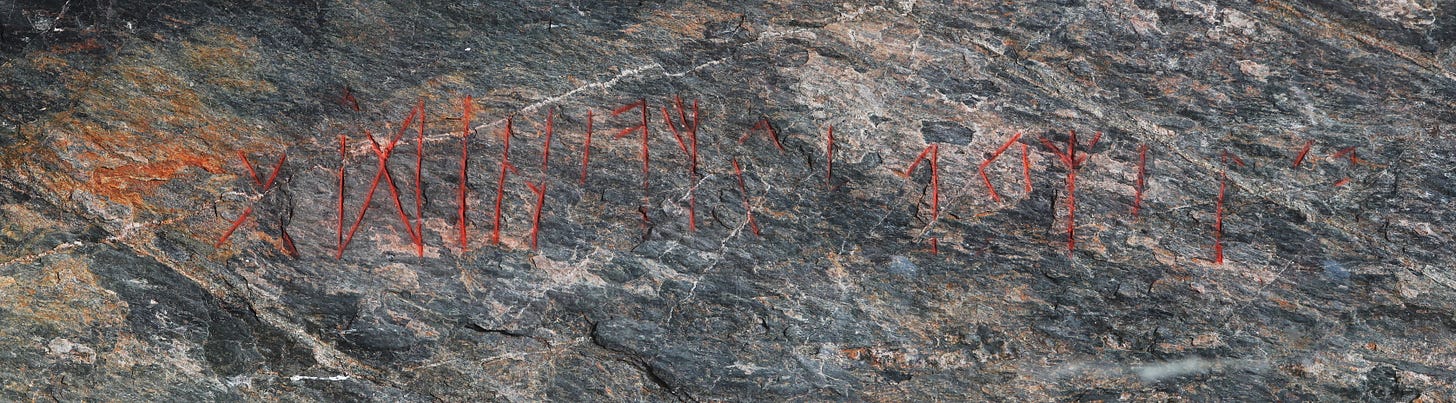

When I emerged I was crouching just exactly like the Terminator crouched after his own time-travel journey, and my side was pressed against a large rock. On it were Nordic runes, short twig, and I caressed them and felt every bead of sweat from every careful tap of the chisel, the aching back, the groaning forearms. That I could not read them was unsurprising, and as it happens irrelevant. They told me what I needed to know: that I had found myself in the world of my ancestors, somewhere and some time in “Northern Europe,” a place of Swedes or Dutchmen or Danes, before they had names. I walked the plains of a land and time that did and did not exist, that is and was and was not real. Dim mists troubled the fjords, and in the inlet I saw antique longships straining calmly forward. I spied a warrior whose helmet wore horns, because I was not in the world but in the word. I’m sure some buxom blonde she-warrior was wandering around somewhere, posing for cameras that didn’t yet exist. The smell of burning pyres wafted intermittent and the water sank into itself in a deep and rippling azure and there was game to be found in the forests and cold iron with which to kill it. I never before breathed such air. But though this might sound like an alt-right fever dream, prelapsarian, pure, in this space I was despondent, disgusted, for I saw the universality of human need and the inevitability of nature’s cruelty, felt for the first time that certain form of compassion that was an invention of modernity, knew that its nonexistence would be followed by millennia of denial and, if we’re lucky, by fragility. Futility remains to be determined.

Nauseous, I stumbled blinking down an embankment. To keep my balance and my stomach, I clutched a loose crow feather to my temple, reminding myself of the myth of sentience and of the black to which all things ultimately belong. I came to level land, looking back and grasping for the first time how steep the mountains rose behind me. A small village of thick beams and thatched roofs spread out ahead of me. At the outskirts a priest stood ringed by followers. By his side, a goat was tied to a stone altar, covered with its own deep runes, ruddy and worn. He shouted and gesticulated and pointed a crooked knife towards the sky. His dévots seemed content to rock and hum, filthy and entranced. The goat merely breathed, perhaps exhausted, perhaps resigned, and the coming violence was clear. And yet though I sat there for long hours, taking a seat, dirtying my jeans, alone and ignored by the pure indifference of premodern men, he never took the knife to the goat’s neck, never let his shivering congregation reach climax, never brought me the cold finality of the cessation of life. The blade was groaning for use, but he never struck. All he did was shout. He had his audience. He could not consummate his purpose.

I gave up and wandered to a fetid mead hall. Inside an old woman clutched a shaking baby, dabbing buttermilk into its slack mouth. I took a wooden mug that sat in front of a blonde man with no left hand, who blinked in indifference. The mead was disgusting but it felt warm in the dim hall. I rubbed my eyes and looked around and found that it was more crowded than I thought, but the people were drunk and distracted, intent on the lines in their palms, on the bottom of their cups. I asked a bloodied warrior with a gangrenous foot what there was to do around here. By some magic we understood each other. He told me there was a soothsayer, and that she was cheap, but that she only saw what you wanted her to see. I thanked him, ate a crust of maggoty bread, and made my way outside. In no time at all the world had passed from a stinging bright sun to a moonless dark, only stars to see by. I tried to orient myself with the flicker of distant fires. For awhile I stumbled around in mounting panic, unsure of how I would find the runes again and sure that there was no other writing to be found. Then it occurred to me that I had a pen in my pocket, a nondescript black ballpoint. I scrawled “CROATOAN” on my palm, ran my finger across the sweaty ink, and was sucked forward towards the distant future. I had no desire to return home.

This time I did not tarry in the wormhole, other than to read the fine print in the offer sheet we are all given at conception, the Great Deed, the immortal contract that binds us to being mortal, God’s own terms of service, the will to ourselves that we all write in the sky. It was boring.

I found myself in 3023. The world was flat and featureless. No cyborgs roamed the expanse, no mechas prowled the plastic forest, and the robots that busily performed our duties were real, which is to say that they were incapable of inspiring. Zombies were still confined to myth and folklore, and white seekers still sat cross-legged, playacting daijo, begging themselves in thoughts not to think. There were no flying cars, though the elevators were incrementally faster. Cancer had been cured. Hunger had been eliminated. Energy was clean and free and abundant. Bedsheet technology made fitting one on a mattress convenient and easy. There were still mountains in the distance, but the trees that covered them were not trees, the mist that touched it artificial and unconvincing. Clothes hung beige and synthetic on artificially chiseled bodies. Everyone worked in HR. No one was in any pain.

It took me only a moment to look around and comprehend the horror: it was only this world. It was still only our world. The bargain hadn’t changed. The world was still boring. The prize for success was still disappointment. Desire rose in tandem with the satiation of desire. You had everything you needed and nothing you wanted. Life was the same. Oh, profound technologies had been developed, and companies had risen and disappeared, and countries had crumbled, and culture had turned more times than anyone would care to count. But person after person walked with a slight hurry, chin pressed against their chest, and I sidled up to them, and they were whispering anxiously about filing their income taxes. I looked around for writing but found no novels, no plays, no poetry, no songs. All I found were documents. The word had only a few sad forms left, and they had sick meanings if beautiful sounds, like that word of sad ironic intense beauty, “indemnify.” All that was left of writing was its ability to constrain. And the people still started the weekend dreading the week to come.

Alone and friendless, I shuffled around in a world of soft edges, the colors of a nursery. Eventually I flew home. The wormhole was colorless, frictionless. When I got back to the park, I threw my pen into a steam that's driven by a pump. There was no point to traveling through time by means of the word; past, present, and future were all the same. In all three times, above me, the same white clouds pinnacled the same grey sky.

'Everyone worked in HR.'

This was how I was sure that we'd been transported to Hell.

This is the sort of piece I want to read twice: once to understand at an intellectual level, and once again to feel it, to float along its stream face up, letting the language carry me through the beautiful and the terrible.