I had one little run in with Elizabeth Wurtzel, some five or so years ago. We were both on a panel on some sort of web talk show, streamed in via Google Hangouts or whatever. There were maybe four of us and a host. I could not tell you the topic of that conversation if my life depended on it, much less the name of the show. But I do remember her. Before the show began, we were all sitting there, waiting, and it was awkward, or it would have been, had she not started talking. She talked quickly and confidently. She asked me about “my deal,” and before I knew it we were talking about my cat. She was forward and endearingly nosy. She seemed completely at home with herself. And then the show started, and I said some stupid pablum when my time to talk came and it was over.

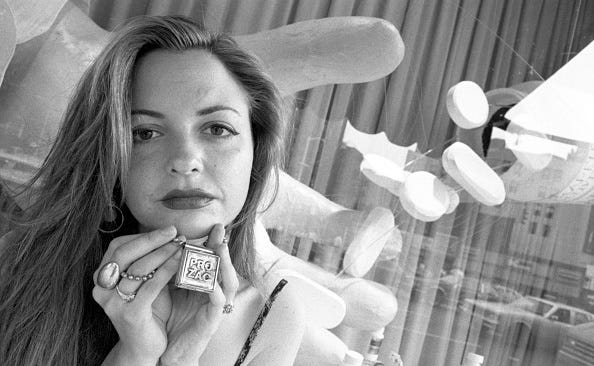

I read Prozac Nation when I was a young man, in my early twenties. I devoured every page, finishing it in a week, and hating her the entire time, which if nothing else proves once again that there is only one hatred: the hatred of recognition. I’m told that “reading,” in the drag world, refers to the act of sizing someone up so completely that you gain power over them. If I have that right, then she read me while I was reading her. For if my illness is now defined by mania, my young adulthood was defined by depression. I think back to my first little studio apartment and I can’t imagine a worse house of horrors, the endless hours spent curled up in the fetal position on the carpet. And I think about her book and I can’t quite grasp why I was so repelled by the familiar. I suppose the only honest answer is that I was not looking for honest answers. Not then. Back then I was running.

What I didn’t know at the time was that she understood things I couldn’t see. What Wurtzel grasped was that there was no percentage in trying to soft pedal a disease that would give no quarter if she did. She understood that behind depression there’s just more depression. And so why not try to do the impossible and put into words that which comes to be the defining facet of your life? Depression is a negotiation, made against someone who has all the leverage. You can, perhaps, improve your negotiating position with drugs and therapy. But the actual experience of depression will remain visceral no matter how hard you try to render it banal. There simply was no value, to her, in trying to make others feel more comfortable about the spiraling instability that was her early adulthood. This might sound selfish but in reality it’s the kind of internal bargaining that could only be made by someone who thoroughly knew herself.

Was her work pretentious and self-absorbed? Sure. But she never claimed to be otherwise. Depression makes you myopic; hurt develops its own kind of gravity, and over time everything falls in, except those people with foresight enough to see that they are approaching the event horizon and step away in time. You will not be saved by trying to maintain the requisite ironic distance from your own life, to act like some 21st century Twitter power user who deadens their experience of life with jokes and memes and cleverness. She chose to do the opposite, and being a writer, she did it with words: she wrote down what it means to be depressed, and what it mean to be a brilliant beautiful Gen X degenerate, and she did it as good as any and better than most.

Besides, I’ve been an advocate for pretension for a long time. What you gain from refusing to be pretentious is, I guess, becoming a harder target to hit when people inevitably come to dress you down. That’s the only upside I can see. And the downside? You become a stranger to yourself. You are so consumed with not being pretentious that you leave beside anything deep, penetrating, and true. You doubt your own reaction to beautiful people and perfect art. You are scared to bare your undershirt, let alone your soul. You know that there is always a built-in limit to the ecstasy of any experience. You become a slave to your own self defenses. You are neutral in all the places where neutrality makes you boring. You are afraid. Me, personally, with my life, my personality? How could I have ended up any other way than pretentious? And for those of us in that position, there is Wurtzel to say, fuck them, if it’s pretentious say it anyway. Say it anyway.

In Prozac Nation “I can just hear the words ‘inoperable brain cancer’ being whispered to me by some physician twenty years from now.” This too is a preoccupation of the depressive. I suspect it’s because cancer is the realest illness, the most visceral and the hardest to deny. Surely that has great appeal to those who, like the depressive, have been told in voices both loud and soft that their illness is not real and that their concerns are those of the coddled. Breast or brain, cancer can kill you; I suppose it was only fitting that a person held captive by her own mind would become convinced that it was her mind that would kill her. Now it makes me think of Trumbull Stickney, who wrote

Sir, say no more.

Within me ’t is as if

The green and climbing eyesight of a cat

Crawled near my mind’s poor birds.

I look back now at my earlier self, the one who was so hard on Elizabeth Wurtzel for articulating everything I felt and could not bear to say, and I can only think of one thing: my certainty, at one time, that my resolve mattered, that what drugs and doctors couldn’t do, my will could. If I am being honest, that is the biggest change in my life from those days when I would count the grains of sand in the paint on my ceiling: I have surrendered. I have learned that I am not strong enough, and that even if I could summon the strength, there was not much worth saving.

Elizabeth Wurtzel knew intrinsically what took me decades to learn. She knew that depression, like cancer, was no tame animal, that it took who it chose when it felt like taking them. And so she made up her mind to describe it as fully and forcefully as she could, undeterred by the inevitable criticism, determined to try and express feelings that undermine the foundations of the language in which you express them. She did not deny her illness, nor try and sand off the edges that came along with it. She understood that she had no power over her illnesses but the power of description, and so she described. Her descriptions were true, as true to depression as has ever been written, and they will endure. She knew things, like the price of telling that truth. And that for her, and for me, and for you, the bargain with cancer and with depression remains the same: the fates will decide, and you will survive, or be consumed.

I am traveling until at least May 3rd and will not be available to read comments. Comments are therefore unmonitored and unmoderated until I return. If you feel that a comment has violated Substack’s Content Guidelines, please email tos@substack.com.