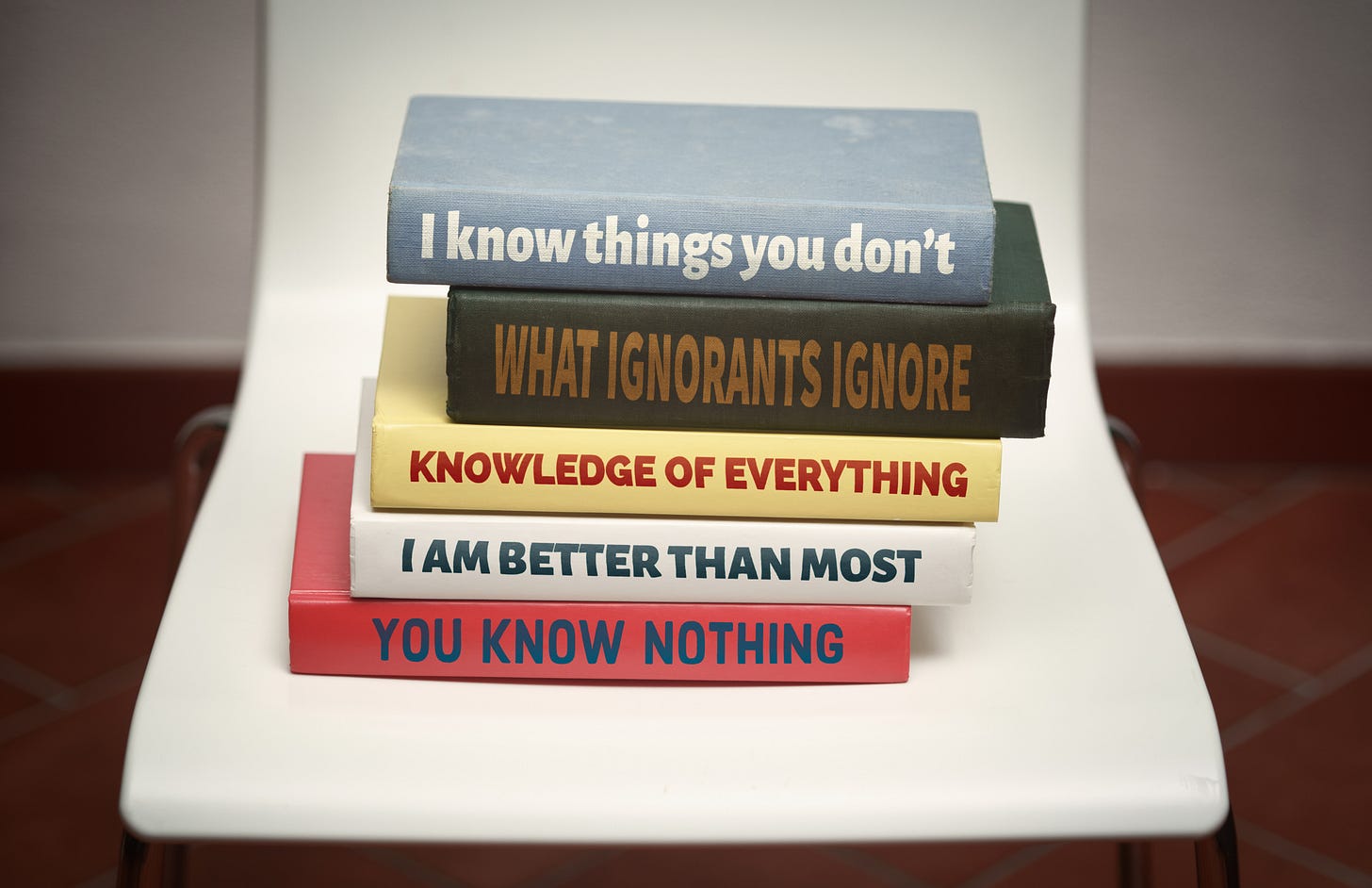

Do You Hate Catcher in the Rye, or Are You Just a Ball of Perpetual Insecurity and Self Doubt?

like 90% of cultural elite bullshit would be cured if they had healthy sense of self

This is the second post in (the first annual?) Lit Week at freddiedeboer.substack.com

It seems the crowd has turned from performatively hating David Foster Wallace to performatively hating The Catcher in the Rye. (That tweet is just the seed of a whole tiring conversation.) As usual, this is mostly expressed in terms of vague, quasi-political complaints about the author or book’s proximity to an equally vague notion of masculinity; Catcher in the Rye is a boy book and Charles Bukowski is a boy writer and Hemingway writes about boy stuff and this is somehow meant to be deeply embarrassing for their fans. As I said about Infinite Jest, this stuff has the strange knock-on effect of further elevating the targeted authors and books as important, while conspicuously not improving the fortunes of the books they’d rather you read instead. But people really, really enjoy letting everyone know which books or authors are “deal breakers,” a concept promulgated by people who seem to think that there is no use for books other than serving as criteria for who you would be willing to make out with behind the bleachers during free period. There are many actual lists of books that you are forbidden to read if you want the approval of a lot of sneering and dismissive readers who, I suspect, don’t read.

For the record, I think The Catcher in the Rye is… OK? It’s fine. It’s definitely a book of an earlier era and it felt as such when I read it as a teenager. I was hoping to connect with it on a deep level (uh, not a Mark David Chapman level) the way some adults in my life had, and I didn’t and was kind of bummed out. But it was fine. As is so often the case with these things, there’s a really dumbass reading of the book lurking in the discussion about it, which is that you’re somehow commanded to identify with Holden Caufield and to want to act like him. This is… not a good interpretation. You certainly can identify with him, but I don’t think that’s suggested very strongly, let alone mandated. As with Fight Club, another boy story for boys about boys being boys, you are invited to empathize with the alienation and loneliness of the main character while recognizing the juvenility and pointlessness of his reaction to it. But, well, now I’m actually engaging with the book, which is more than social media critics of books ever do. They never seem to want to go deeper than saying “TOXIC MASCULINITY” or whatever, which is particularly bizarre here. (Is the idea that Holden Caufield is supposed to be some sort of symbol of an idealized man? What?) It’s all uselessly Manichean - I know this headline is partially a joke but it makes me wince anyway. The important work is always to say a) this book/author is bad and b) liking it is not a matter of bad taste but of some sort of failure of political and moral sophistication.

My feeling with this shit is always… why bother? You don’t like a book. Wow. I didn’t like John Grisham’s The Firm but you don’t see me constructing an entire fucking personality out of it. But the obvious answer to “why bother?” is that this expression of showy contempt has nothing to do with reading at all, and instead everything to do with appearing to be a certain kind of person. There’s a clique that endlessly declares certain books or authors to be low status in bizarre and undefended identity politics terms, and if there’s a group that affects a showy disdain for others and hordes insider status you can guarantee that insecure people will flock to them. If you like what a clique likes there’s a built-in sense of protection; how can your tastes be ridiculous and worthy of mockery if other people share them, especially other people who argue with such conviction? This is why this tendency is more prevalent with books than with any other medium: insecurity about reading and books is common even among many bookworms, in a way that is not as true with music or movies.

The problem with adopting this self-defensive association with people who are still obsessing about David Foster Wallace in 2021 is that it leads you to bizarre conclusions and degrades the purpose of books. I mean, in the most absurd expression of this tendency merely reading a book is assumed to associate you with its argument and author and culture. Like when people say “I saw this guy with Atlas Shrugged on the subway, it was so cringe.” Literally, what the fuck are you talking about? Have you never imagined reading a book without wanting it to be a signifier of your entire personality? Do you know how many books I’ve read specifically because I hate the author and their outlook? Or, quelle horreur, you could consider reading a book without knowing what you think about it until you’ve read it! You know, the generative state of being open to forming a summative position based on the gradual aggregation of myriad minor judgments formed along the way? That would seem to be a major part of the point of reading. Even if someone outwardly professes to like a book that you don’t, I haven’t got a clue what you think that fact in isolation teaches you. Interests? I have a copy of Be Here Now on my shelf. I’ve never meditated in my life. Intelligence? One of the smartest people I know has a Family Guy tattoo. People are strange and a lot of cool people have shitty taste. Just a bizarre series of assumptions all around.

It’s a sickness, the assumption that we must always tightly control every last aspect of our self-presentation, no matter how distinct from our true self, because someone on the subway with a $300k education and zero opinions they didn’t steal from podcasts might silently judge us. And as (this philosophy presumes) no one has a durable sense of self worth, being judged by strangers must be terrifying instead of meaningless.

Many have lamented the fact that professional criticism these days is often just a recitation of ways that a work of art does or does not conform to the childish moral calculus of “social justice.” And mountains of worthless reviews and recaps have been produced under these terms. But it’s important to say that this tendency is not solely or even mainly the product of ideological discipline and the desire to evangelize. Rather it stems from insecurity about one’s own subjective opinions. People who don’t trust that they are sophisticated readers or cinephiles or whatever gravitate towards tedious political checklisting because those political claims seem more transcendent and defensible and real than their own claims of taste. But this fundamentally mistakes the purpose of a review, and it’s very hard to understand why someone who is so afraid of standing by their own opinion would think to write one.

When I review something I speak ex cathedra not because I think that my opinion is the only correct or true one but precisely because I know that it is my own. That’s what a review is, your opinion, your observation, your analysis. And those are sacred. I’m not afraid to speak with confidence about my feelings towards a book or movie or show because I am the world’s foremost leading expert on my feelings, and I am prepared to defend those feelings with evidence and analysis. If you don’t feel confident enough to make your criticism about your subjective opinions and to defend them as such, rather than to give up your opinion in favor of political clichés… why are you writing a review?

People think I hate media culture because it’s woke. No. I interact weekly with IRL activists who are painfully woke and enjoy friendly and comradely relationships with them. (Thankfully, symbol-and-language-obsessed social justice politics are not actually very relevant to the day-to-day work of organizing and mutual aid.) And it must always be remembered that, not that long ago, most media elites were not woke, but rather sneering neoliberals who mocked leftists as losers; the fact that media culture turned on a dime to embrace social justice fads makes it a certainty that, when that politics goes out of fashion in the coming decade, the media will flip flop right over again. No, the problem with media culture is not the politics but rather where those politics come from - not just from elite colleges or privileged childhoods lived in affluence, but from insecurity. Many individuals in media are lovely people, smart and talented and in possession of normal, healthy self-ownership. But as a class they are desperately insecure and driven by status anxiety. Like almost everyone who spent their adolescents climbing the status ladder, they feel unsafe and unmoored outside of the comforting order of SAT scores and piano recitals. Woke politics offers them the ability to farm out all of their opinions to memes and Twitter; it’s a readymade ideology, something you can buy off the rack. As long as you make sure to parrot your perception of the dominant position on any issue, you’re safe.

I don’t have the slightest idea why you’d want to be in the writing or reporting or analyzing business if you’re that afraid to stand on your own, but the media is an industry of indoor kids, grown up and eager to ascend in a new popularity hierarchy, to be one of the queen bees for once. They are approval seekers by nature; insecurity is the shackles of our class, and of our cultural era. When you make these ostentatious pronouncements not about David Foster Wallace or Salinger or Bukowski or whoever, but rather your conception of their readers, it doesn’t make you look sophisticated. (And it certainly doesn’t create political change lol.) It just makes you look like someone who isn’t good enough at having opinions to have any of your own.

But the solution is blessedly easy: to understand, deep inside of yourself, that you are as good of a reader as anyone who has ever read, that your opinions about books are as valid and real and deeply felt as any that anyone has ever held, and that your value (as a reader or as anything else) is not the sum or the average of the opinions of other people. No, all opinions are not of equal value, much less the expression of those opinions. But all people have the same capacity for strength in holding them. And if you believe that your opinion is endowed with importance because you hold it and for no other reason, as you should be, then you should go out loving what you love and hating what you hate, authentically and organically, and express it without reservation, certainly if that still means hating DFW or Catcher in the Rye or Bukowski. “I hate The Catcher in the Rye” is not a less meaningful or powerful or sophisticated statement than “all my friends agree that The Catcher in the Rye is cringe”; it’s a statement of vastly greater value. Farming out your aesthetic opinions to some strangled ideal of the collective cool kid consciousness is worse than afraid and less than trite; it’s a refusal to take yourself seriously.

Taking yourself seriously is not pretentious and it’s not self-important and it’s not arrogant. It’s a recognition that neither the world nor anyone in it can ever give your life meaning for you. You might think that this is remote from the concept of having your own opinions on art, but it’s not; the only thing that you can ever have that is truly yours is your conviction, your vision of what is right in life and what is not. You should try having such conviction, and if you can ever achieve a normal and healthy level of self-ownership, you should ask yourself - do I really give a single fuck about The Catcher in the Rye?

You mention insecurity, which is indeed at the root of it. Think about the guys in High Fidelity. Why do they endlessly obsess over musical taste, question each other’s taste, sneer at the taste of others? Because they have erroneously mapped onto “taste” the drive to acquire useful knowledge and skills. Ordinarily, young people in the prime of their lives should be acquiring the skills and knowledge of their people, in order to contribute to the survival of the group. A primary motivator in acquiring such skills is the desire for status, and young people get that need satisfied by developing those skills, proving their worth and mettle, and, often, going through an initiation ritual. Now you are an adult of our tribe — a vital member of the group who helps us survive in a difficult world.

In our society, though, we have made many people somewhat vestigial. Nobody is really that critical to our mega-tribe’s survival, and the ratio of really important positions to people who could do them is alarmingly low. Many people are left with a deep, gnawing sense of uselessness. It’s a profound insecurity that the vast majority of our ancestors never dealt with.

The solution? I must just need to acquire MORE of the skills and knowledge that my culture says it values! To prove my worth I should carve out a niche. I’m the one who knows about cult rock 45s! I’m the one who knows which books signal the wrong sort of ideas! I AM THE ONE WHO TWEETS.

All this activity is completely fruitless, of course (analogous to what David Graeber calls “bullshit jobs”), but it momentarily salves the anxiety.

This is, again, the transition between the third and fourth stages of adult cognitive development. Stage four of cognitive development has an internal structure of justifications, where stage three cannot process the world through anything but popularity contests.

That $300,000 education you mentioned used to solidly provide a transition from three to four, up until poorly-understood pseudo-postmodernism undermined it in the humanities. (Although it could not do so in STEM, which is why STEM majors took over the world.)

At the risk of every one of my comments here being repetitious, this is yet another reason I would like very much to know what you think if you read Robert Kegan. It seems to have explanatory relevance for every topic you tend to discuss most often. "In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands Of Modern Life" examines the transition between stages three and four specifically.